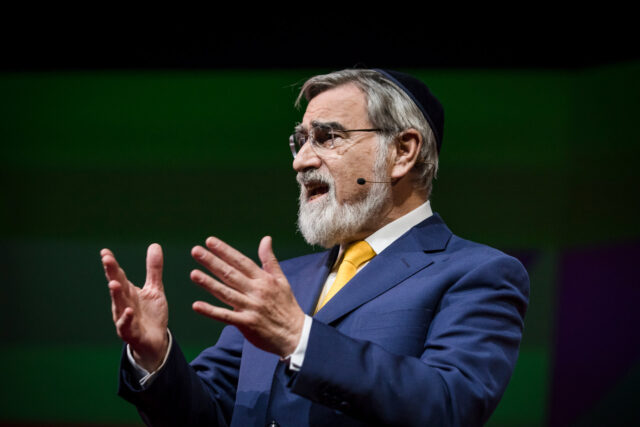

The death of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, on November 7th, 2020 left a gaping hole for Jewry and the world at large. Rabbi Sacks masterfully articulated the ideals of Judaism with sensitivity and profundity, using his impressive breadth and depth of secular knowledge to bring the Torah’s wisdom to life. His messages of morality were universal and have influenced countless lives. Many have begun to analyze the enormous amount of Torah Rabbi Sacks has left behind, but much work remains. A central idea that Rabbi Sacks returned to repeatedly over the last several decades of his life was the idea of Guilt and Shame[1] cultures in the Torah and contemporary society.

A deeper analysis of this topic is important due to its enormous continued relevance. We live in an era of intense social discord and distrust. Countries, communities, and families are torn apart from political disagreements. The need to conform to the in-group has caused those with differing opinions to remain silent, afraid of cancellation or ostracization for uttering the “wrong” viewpoint. We have forgotten how to disagree and forgive, how to see the image of God in those different from us. We have become more concerned about our perception than our true character, resulting in a schism between our outward lives and our true essence. We have lost ourselves in our own fear. How do we heal our fractured world? What can we do to see the dignity in others’ differences? The answer to these questions lies in the teachings of Rabbi Sacks, and it involves transforming our society from a Shame Culture to a Guilt Culture.

Ingredients of Guilt and Shame Cultures

American anthropologist Ruth Benedict first formulated the differences between Guilt and Shame cultures in the 1940s to aid the U.S. army in its war against Japan.[2] This conceptualization has remained popular in contemporary cultural studies, and it deeply impacted the thought of Rabbi Sacks. Drawing upon Benedict, the Bible, and a variety of other sources, Rabbi Sacks identified three key differences between Guilt and Shame cultures that informed his interpretive approach.

Firstly, in Guilt cultures, morality is based on one’s inner conscience. A person listens to the voice within themselves, what Freud called the superego, to determine the difference between right and wrong. In Shame cultures, by contrast, the reaction one would receive guides people’s behavior. These two different forces, one internal and the other external, produce distinct psychological feelings: Disobeying one’s conscience produces guilt; having one’s nonconforming behavior discovered by others produces shame.

Rabbi Sacks believed that this difference stems from the notion that individuals in Guilt cultures, such as Judaism, see themselves as actors in front of God, whereas individuals in Shame cultures view themselves as actors in front of society. Consequently, individuals in Guilt cultures live with the inescapable inner torment that they can never fool God. They live, regardless of whether other humans see or judge their actions, with a profound sense of guilt. When practiced ideally, this guilt should not be debilitating or overbearing, but rather a healthy tool to recognize the importance of one’s inner-conscience and to take practical steps to heed to its call.

Because Guilt cultures put a heavy emphasis on one’s inner convictions, they are less vulnerable (in its ideal sense) to groupthink. Guilt cultures such as Judaism, in the words of Rabbi Sacks, are “living protest[s] against the herd instinct.” Guilt cultures endow their community members with a sense of personal responsibility in the face of adversity. Shame cultures, in contrast, are collective and conformist; one’s public image matters more than one’s inner voice. Consequently, Shame cultures have little room for honesty and sincere apologies, because if people could save their image by denying the mishap or by blaming others, there would be no need to self-scrutinize to cleanse one’s conscience.[3]

Rabbi Sacks’ postdoctoral supervisor, Bernard Williams, astutely observed a second difference between Guilt and Shame cultures.[4] Since they are fundamentally concerned about their public image, individuals in Shame cultures heavily emphasize how things look to the eye, whereas Guilt cultures emphasize how things sound to the ear.[5] Accordingly, Rabbi Sacks contrasted the Bible with ancient Greek literature. Biblical texts, the inspiration and foundation for Guilt cultures such as Judaism, hardly mention appearances: “Jewish culture is so non-visual that we don’t know what anyone looks like.” With rare exceptions, it is up to the reader to imagine how the characters and objects of the Bible appeared.[6] However, ancient Greek literature, typical of Shame cultures, heaps lavish praise upon its art, architecture, and physical bodies. The Bible’s relative silence about these things, Rabbi Sacks argues, tacitly champions the inner ear and listening to life’s deeper messages beyond the shallowness of what meets the naked eye.[7]

Finally, Rabbi Sacks formulated a third fundamental difference between Guilt and Shame cultures: the former separates sin from sinner, agent from act, whereas the latter views sin and sinner as inseparable. In Guilt cultures, people’s actions can be bifurcated from their essence because they are capable of change and repentance. The Jewish prayer, “My God, the soul that You gave me is pure,” remains true even in the face of sin or failure. This idea allows one to separate sin from sinner because one can always return to the good of their soulful essence. As a result, their past mistakes don’t have to haunt them forever. In Shame cultures, however, a person’s sin or mistake remains a permanent stain. Since one’s image matters more than self-improvement, change and repentance are of little consequence. The sinner remains a pariah, without options for redemption and reacceptance into society. Because Guilt cultures separate sin from sinner, they not only allow for repentance toward God, but they also give way to the concept of forgiveness between people when change is sincere.

It is not surprising, then, as Rabbi Sacks noted, that ancient Greek literature produced the literary genre of the tragedy. The shamed “hero” dies in battle or flees to a remote country, never to be seen again. In contrast, Guilt cultures produced literatures of hope and affirmations of life. Even after failure, such as King David with Bathsheba, the hero confesses, repents, and is able to begin again, without being held captive to his past. Suicide is deeply frowned upon, and never a valid solution to life’s problems. To be sure, ancient Greek literature depicts something that approximates forgiveness. However, as American classicist David Konstan points out, it is closer to the concept of appeasement than forgiveness.[8] One achieves appeasement by showing deference and subjugation to the person slighted, while forgiveness occurs when one recognizes the sincere change of character in another. Primatologist Frans de Waal showed that chimpanzees engage in appeasement rituals to restore group harmony.[9] However, according to Rabbi Sacks, it is an entirely human endeavor, and one germane only to Guilt cultures, to truly forgive another.

Guilt and Shame Cultures in the Torah: Adam and Eve, the Patriarchs, Metzora, and Yom Kippur

Beyond the above examples, Rabbi Sacks ingeniously used these three differences between Guilt and Shame cultures to explain many parts of the Torah. In each case, we find a remarkable textual analysis and novel interpretation.[10] Rabbi Sacks used these motifs to explain the story of Adam and Eve, the patriarchal narratives of Abraham through Joseph, and the counter-examples of metzora and Yom Kippur.

The origins of Guilt and Shame cultures in human society, Rabbi Sacks explained, begins with the story of Adam and Eve. Before the sin of eating the forbidden fruit, the text describes both Adam and Eve as naked and unashamed (Genesis 2:25). Eve then sees the fruit and describes it as “desirable to the eyes.” After eating the fruit, Adam and Eve become aware of their nakedness. The Torah then describes that Adam and Eve “heard the sound of God moving about in the garden at the breezy time of day; and the Human and his wife hid from God among the trees of the garden” (Genesis 3:6-8).[11] According to Rabbi Sacks, Adam and Eve sinned by following their eyes over their ears. Eve’s statement that the fruit was “desirable to eyes” represents Shame cultures’ emphasis on outer appearance. Adam and Eve drowned out the prototypical inner conscience of Guilt cultures as manifested in the commandment against eating the fruit, and followed what looked ostensibly appealing instead. The sin resulted in Adam and Eve experiencing shame of their nakedness, a metaphor for acquiring the ethic of shame. Whereas prior to the sin Adam and Eve possessed a guilt ethic in which it was much easier to follow one’s inner voice, the sin resulted in humanity waging a perpetual battle of shame versus guilt, of what one knows to be internally right versus what looks appealing. By eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad, Adam and Eve, and all of humanity, obtained a new knowledge of how our behavior appears to others. That type of knowledge, however, can cause tension with our inner conscience, thus making life’s decisions more difficult. From then onwards, humanity was challenged with balancing the need to listen to our inner voices and the desire to conform to societal norms.[12]

Rabbi Sacks extended this analysis to the stories of the Patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob, and Joseph as well. For Rabbi Sacks, no one exemplified the trait of inner conviction more than Abraham. According to Rabbi Sacks, God’s first statement to Abraham—“Go forth from your land, your birthplace and your father’s house to the land that I will show you” (Genesis 12:1)—represents not only a physical journey but also leaving the external influences of his homeland to become the father of an inner-directed people. This conviction inspired Abraham to refuse to conform to his surroundings and to metaphorically be “on one side of a river while the rest of the world was on the other” (Genesis Rabbah 42:8). Abraham’s ability to swim against the tide is the reason God singled him out with the mission “that he may instruct his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is just and right” (Genesis 18:19). The astonishing resilience the Jewish people have displayed throughout their history by being able to survive and thrive in times of change, exile, and tragedy is a gift bequeathed to them by their ancestor Abraham.

Rabbi Sacks similarly employed the concept of Guilt culture to explain the story of Isaac and Rebecca. Rabbi Sacks based his interpretation of the relationship between Isaac and Rebecca on the comments of Netziv. At the first moment Rebecca sees Isaac, Rebecca “covered herself with a veil” (Genesis 24:63), which, according to Netziv, represents the idea that Rebecca felt inadequate to be Isaac’s wife.[13] Netziv says that this feeling of inadequacy led to a fear of criticism that ultimately spiraled into a lifetime of communication issues between Isaac and Rebecca. For example, it seems that Rebecca never communicated to Isaac that an angel informed her before Jacob and Esau were born that “the elder will serve the younger” (Genesis 25:23). If she did, it would be hard to explain why Isaac loved Esau more than Jacob and intended to bless Esau instead of Jacob. It also explains why Rebecca opted for deception, by having Jacob pretend to be Esau, instead of simply communicating with Isaac why she thought Jacob was more befitting of the blessing. Had they spoken openly about it, perhaps Isaac would have agreed with Rebecca or, as Rabbi Sacks argues, Rebecca would have learned that Isaac planned on blessing both Jacob and Esau, each one with the blessing that best suited him. The lack of open communication resulted in Jacob fleeing from Esau for two decades and causing eternal strife. For Rabbi Sacks, this story is a tragedy, as it fails to live up to the ideals of a Guilt culture. When we lose the ability to separate sin from sinner, criticism becomes a personal attack and rejection of the other’s essence. The fear of that rejection prevents the powerful tool of open and constructive communication.

Elsewhere, Rabbi Sacks extends this analysis to Jacob’s fateful encounter with Isaac. Following Rebecca’s lead, Jacob donned Esau’s clothing and served Isaac venison to deceive Isaac into blessing him (Genesis 27:15). Rabbi Sacks points out that this interaction between Jacob and Isaac refers to all of Isaac’s five senses (Genesis 27:22-27) except sight, because Isaac was blind (Genesis 27:1). According to Rabbi Sacks, the emphasis on the senses reveals the message of the story. Isaac’s sense of sound, representative of Guilt cultures, indicated that Jacob was seeking the blessing. The other senses of touch, taste, and smell, however, indicated the presence of Esau. Isaac ignored his ear, his inner conscience, that told him “the voice is the voice of Jacob” and instead followed the illusion of the physical world. In essence, Rabbi Sacks maintains that Isaac erred in much the same way that Adam, Eve, and Rebecca did before: They ignored their ethic of Guilt and pursued the false hopes associated with an ethic of Shame.

Rabbi Sacks’ analysis of the Patriarchs concluded with the story of Joseph, which fleshes out the forgiveness element of Guilt cultures. Rabbi Sacks often cited David Konstan, who boldly asserted that the story of Joseph forgiving his brothers for selling him as a slave is the first instance in the literary history of forgiveness.[14] Upon hearing his brothers beg for forgiveness, Joseph passionately responds, “do not be distressed or reproach yourselves because you sold me hither; it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you” (Genesis 45:5). Joseph, with his ability to separate sin from sinner, recognized that his brothers were now different people and worthy of forgiveness. “Humanity changed the day Joseph forgave his brothers,” wrote Rabbi Sacks. “When we forgive and are worthy of being forgiven, we are no longer prisoners of our past.”

While Rabbi Sacks repeatedly urged his audience about the importance of Guilt cultures, he also acknowledged in his analysis of the metzora and Yom Kippur the place of a shame-ethic as well. The metzora is a person whose house, clothing, and eventually skin become discolored. Rabbi Sacks adopts the view that metzora’s common English translation of leprosy is erroneous, as its symptoms and laws bear little resemblance to leprosy or any other contagious disease. Rather, tzara’at is a spiritual malady, one the Sages say results primarily from lashon hara, evil speech or gossip (Arakhin 16a). Surprisingly, the Bible’s directives for “curing” this affliction share much in common with the punishments of Shame cultures. The appearance of discoloration on the walls of a house, clothing, and body serve as public signals of wrongdoing that lead to social stigma. Exile is the ultimate form of ostracization.

Rabbi Sacks explained that although, as we have seen, the Bible promotes a Guilt culture, it acknowledges, and even mandates, a place for shame as well. Shame is necessary in this instance because there is nothing as detrimental to the unity of society as lashon hara.[15] Anthropologists have argued that language evolved amongst humans in order to strengthen society, and by speaking lashon hara, one undermines the basic trust that holds society together. Whereas other sins could be punished using the normal ethic of Guilt cultures, something as dubious as lashon hara could only be punished through public condemnation and shame. “The best way of dealing with people who poison relationships without actually uttering falsehoods,” argued Rabbi Sacks, “is by naming, shaming and shunning them.”

We find a similar analysis when it comes to Rabbi Sacks’ understanding of the most guilt-laden day of the year, Yom Kippur. On this Day of Atonement, Jews repeatedly confess their sins in alphabetical order. However, Yom Kippur is not just the day of guilt; it is also the day in which God forgives us, which is perhaps why the Talmud lists Yom Kippur as one of the happiest days of the year (Ta’anit 30b). With the knowledge that our sins are separate from our essence, we are able to engage in repentance and be forgiven by God.

In addition to Yom Kippur’s ethic of Guilt, Rabbi Sacks pointed out elsewhere that Yom Kippur has shame-ethics too. During the era of the Temple, one of the main Yom Kippur rituals was the lottery of two goats, designating one as a korban asham (guilt offering) in the Temple and sending the other into the desert to throw off a cliff (Leviticus 16:7-22). In explaining the symbolic nature of these two goats, Rabbi Sacks cited a verse that implies two distinct elements of the Yom Kippur atonement process: “On this day you shall have all your sins atoned [yekhaper], so that you will be cleansed [le-taher]” (Leviticus 16:30). Yom Kippur includes kapparah, atonement, and taharah, cleansing, which correspond to two different types of sins: Atonement is the forgiveness of sins against God, cleansing rectifies the sins against the community. Sinning against God, against one’s inner conscience, fills one with guilt. As its name suggests, the guilt offering symbolizes the atonement achieved in this arena. However, the psychology of sins against the community fills the sinner with shame. When we sin against others, Divine forgiveness is insufficient because the sinner retains a sense of shame and humiliation that their misdeeds are known to others. According to Rabbi Sacks, the only way to achieve taharah is through a dramatic and symbolic ceremony pushing the second goat, representing shame, off a cliff.[16] This ceremony relieves the sinner of their psychological sense of shame.

Rabbi Sacks believed that Metzora and Yom Kippur are rare examples in which the Torah promotes an ethic of shame.[17] It is necessary in the case of tzara’at to maintain social cohesion. Yom Kippur, in the midst of a heavy sense of guilt, espouses shame because “that was the one day of the year in which everyone shared at least vicariously in the process of confession, repentance, atonement and purification. When the whole society confesses its guilt, individuals can be redeemed from shame.”[18]

Conclusion

In the last public essay before his passing, Rabbi Sacks reflected on Moses’ farewell address.[19] With his impending death staring him in the eyes, Moses addresses the Jewish nation and imparts his final message (Deuteronomy 32:4-6). In a moving essay, Rabbi Sacks illustrated how the overall message of Moses’ final plea was for the Jewish nation to take responsibility for their actions and to not blame God when things go wrong. Thus, Moses departs with the same message in which the Bible began. Adam and Eve’s refusal to listen to their inner voices and accept responsibility adumbrates the themes of Abraham, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Esau, Joseph, the Metzora, Yom Kippur, and Moses’ farewell address. Following in the steps of Moses, Rabbi Sacks’ final message charged his readers to do what characterized his whole life: heed our inner voices and accept personal responsibility.

Although Rabbi Sacks discussed the differences between Guilt and Shame cultures as early as 2001, it is noteworthy that he began to discuss it much more frequently in the later years of his life.[20] Perhaps Rabbi Sacks did so because he saw a disturbing trend in which contemporary society began increasingly to transition into more of a Shame culture. On several occasions, Rabbi Sacks decried the influence of social media in such terms: “The return of public shaming and vigilante justice, of viral videos and tendentious Tweets, is not a move forward to a brave new world but a regression to a very old one; that of Pre-Christian Rome and the pre-Socratic Greeks.”[21] People are increasingly viewing sin as a permanent stain on the sinner and thus regarding forgiveness as archaic. The fear of being forever canceled and shamed is more apparent than the fear of betraying oneself. “What counts today is public image — hence the replacement of prophets by public relations practitioners, and the Ten Commandments by three new rules: Thou shalt not be found out, thou shalt not admit, thou shalt not apologise,” mused Rabbi Sacks. People are called out for their mistakes instead of being called in to reconsider them, ostracized for nonconformity instead of being appreciated for their diversity of thought. The increased pressure to seem perfect in the public eye has created what is colloquially termed “The Age of Anxiety” and has contributed to a spike in suicide.

Rabbi Sacks urged the world to return to the ethics of the Bible and reclaim the beauty of a Guilt culture. He saw the values of responsibility, repentance, forgiveness, and individuality at risk of being completely lost in a society growing increasingly more fearful of other people’s judgements than of God’s or their own values. After Rabbi Sacks’ passing, it is upon us to heed our inner conscience and carry out this charge.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.