Shaina Trapedo

Yes, Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a plague— a remembrance that has been circulating on the internet, particularly among academics reeling from canceled spring conferences and the abrupt transition to online teaching. Naturally, the presence of pestilence in Shakespeare’s works and the influence of outbreaks on the playwright’s productivity and professional development have drawn attention. And for good reason.

Social distancing hasn’t stopped teachers, performers, and readers of Shakespeare from coming together virtually and sharing messages of hope on social media. In launching the #ShakespeareChallenge on Twitter last month, Simon Godwin professed that “in moments of crisis we need Shakespeare to guide the way.” In a hushed video recorded while her three-year-old daughter napped, Michelle Terry, Artistic Director of The Globe, claimed that there is no industry as resilient, creative, or collaborative as the performing arts to “take on this challenge.” Yet this pattern, or reflex, of turning to Shakespeare for answers to contemporary social, cultural, political, and environmental urgencies certainly predates COVID 19.

For Emma Smith, Shakespeare offers audiences a “narrative vaccine” by redirecting focus from the obliterating obscurity of deadly diseases to “humane uniqueness” and the import of the individual. What makes Shakespeare a panacea, as James Shapiro demonstrates in Shakespeare in a Divided America, is that his plays offer a rare yet fertile common ground for exploring a variety of human responses to a host of human problems. From grief to governance and beyond, the works of Shakespeare have been mined for their timeless insights and assurances.

With Passover, Easter, and Ramadan approaching, like many people I am not sure about how best to observe holidays predicated on gatherings of family and community in light of current restrictions designed to protect the most vulnerable members of our families and communities. The Jewish festival of Passover, in particular, commemorates redemption and the construction of a shared identity. Its practices and liturgy are bound with notions of connectedness, collective memory, and intergenerational continuity. With hospitals filled, synagogues empty, and travel plans canceled, Passover in isolation feels like an oxymoron.

The Haggadah, the traditional text read over the course of the Seder, opens with an invitation: “Let all who are hungry come in and eat. Let all who are in need come and join us.” This hospitable injunction is sure to reverberate more solemnly this year from within the closed doors of our homes. And amidst my downscaled holiday preparations, I found myself wondering: if Shakespeare is indeed the “be all end all,” perhaps he can shed light on how to celebrate Passover in quarantine.

While scholars including Julia Lupton and David Goldstein have explored the risks and affordances of hospitality in Shakespeare that carry over into our own time, I have yet to discover a direct reference to Passover, or the Last Supper, in the plays. However, invocations of the Exodus abound.

The bard’s extensive knowledge of the bible has been studied for centuries. As Hannibal Hamlin notes, “there was no biblical book, including the Apocrypha, to which he did not allude.” In Twelfth Night, when Maria and her entourage humiliate Malvolio by locking him in a cramped dark chamber and making him think he’s gone mad, Feste taunts the presumptuous steward saying “thou art more puzzled than the Egyptians in their fog” (4.2.45).[1] As You Like It’s melancholy Jaques threatens to “rail against all the first-born of Egypt” (2.5.59) if his sleep is disturbed and Lorenzo thanks Portia for gifting him with the deed to Shylock’s estate by saying “you drop manna in the way / Of starvèd people” (The Merchant of Venice 5.1.315).

Shakespeare’s heroines also invoke the drama of the Exodus for heightened rhetorical efficacy. In All’s Well that Ends Well, Helen persuades an ailing, stubborn king to let her try an experimental cure by recalling the supernatural wonders of Moses drawing water from the rock and the splitting of the Red Sea: “Great floods have flown / From simple sources, and great seas have dried / When miracles have by the great’st been denied (2.1.157-159).[2] Most appropriately, in Antony and Cleopatra (also written while the playhouses were closed during an outbreak), the tragic queen beckons the plagues of locusts (“flies” in the Geneva Bible), hail, and death of her firstborn son to afflict her as they did the biblical Egyptians. She counters Antony’s accusation of betrayal by proclaiming that if she has been disloyal, “Let heaven engender hail… The next Caesarion smite, / Till by degrees the memory of my womb, / Together with my brave Egyptians all… Lie graveless till the flies and gnats of the Nile / Have buried them for prey” (3.13.195 – 204).

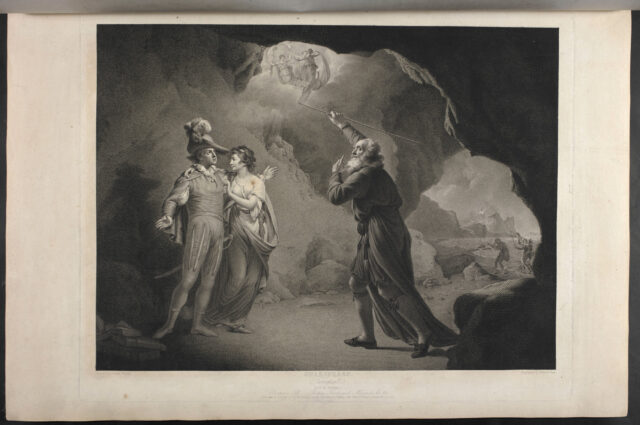

There are far more references to the Exodus than can be cataloged here, and no doubt more yet to be identified by the discerning ear. In a recent Zoom class on The Tempest, my students, who, much like Shakespeare’s audience, have been exposed to biblical literature from a young age through their parochial education and religious leaders, said that Prospero’s conjured storm— with “sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch, / But that the sea, mounting to th’ welkin’s cheek, / Dashes the fire out” (1.2.3-5)— reminded them of the seventh plague in which “Moses stretched out his rod… So there was hail, and fire mingled with the hail, so grievous, as there was none throughout all the land” (Exodus 9:23-24).

And where does Moses, the hero of the Passover narrative, appear in Shakespeare? The bard’s ability to “cite Scripture for his purpose” (Merchant 1.3.107) is especially visible when his characters mention biblical personalities by name— an economical means of activating and illuminating a play’s thematic concerns for his 16th and 17th-century audience. Adam, Abraham, Jacob, Noah, Job, Jesus, and Paul come up in multiple plays. Yet aside from a passing remark about an off-stage outlaw named “Moyses” in Two Gentlemen of Verona, believed to be Shakespeare’s first play, the Hebraic Moses— arguably the central protagonist of the Old Testament and a prominent figure in Renaissance cultural consciousness— seems conspicuously absent from the playwright’s work.

Moses is noticeably missing from another key text: the Haggadah. Aside from a verse quoted by Rabbi Yossi the Galilean in a section discussing the miracles performed during the Exodus, which notes that “the people believed in God and in His servant Moses” (Exodus.14:31), Moses is not mentioned at the Seder table.[3]

It’s hard to say which is more astounding: the monumental role Moses plays in the saga of Jewish life and continuity or the fact that his achievements are denied ceremonial recognition. Following the patriarchs of Genesis, Moses is the Israelites’ first political leader, a divine appointment he famously refuses in his conversation with God at the burning bush: “Who am I, that I should go unto Pharaoh, and that I should bring the children of Israel out of Egypt?” (Exodus 3:11). As a humanities teacher, I am fascinated by the Old Testament’s invitation to engage in character analysis within its own narrative. Moses’s epic struggle with identity and destiny must have captured Shakespeare’s imagination. The bard’s most compelling characters, including Hamlet, Lear, and Macbeth, all confront obstacles that prompt them to ask who am I and why me? When Juliet discovers she’s fallen in love with the only son of her family’s sworn enemies, she quickly grasps the turmoil that ensues when identity comes into conflict with individual will. Her poignant meditation, “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou, Romeo?” (2.2.36) asks not where is Romeo, but why Romeo? Why him? Why me? Why now?

For Shakespeare’s characters, feeling choiceless leads to tragedy, but being forced to reckon with one’s circumstances and selfhood can also be a catalyst to greatness. Like Moses himself, readers of the bible have sought to understand why he was able to connect with the divine so intimately? To singularly speak to God “face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend” (Exodus 33:11)? Put another way, wherefore art thou, Moses?

It is far beyond me to tackle a question that Jewish, Christian, and Islamic exegetes and scholars across disciplines have been grappling with for centuries. The reception and representation of the life of Moses significantly shaped Judeo-Christian theology and the trajectory of Western civilization. As Jane Beal shows in Illuminating Moses, “Moses shaped community standards and influenced the exercise of individual piety for over a thousand years among groups of people who differed widely in geographical location, ethnic language, and religious convictions.”

In Shakespeare’s time, Moses offered Catholics and Protestants alike a model for authorship and hermeneutics, education and worship, and lawmaking and leadership. In Moses, Erasmus found a fellow contemplative, Tyndale a fellow translator, and Philip Sidney a fellow poet. In the Christian tradition, typological readings of the Old Testament present Jesus as a “Second Moses”; just as Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, Jesus led humanity out of sin, through which the law was superseded by grace. Yet the most widely acknowledged of Moses’s virtues is his trademark humility: “Moses was a very meek man above all the men that were upon the earth” (Numbers 12:3). In the modern age, humility is not a quality readily identified in our leaders, and yet, this is the very trait that comes to the fore for Moses in times of national crisis.

Just weeks after being freed from the bonds of Egyptian slavery, the Israelites provoke the wrath of God by forging the Golden Calf. When God tells Moses he plans to wipe out the population with a plague and create a new nation from Moses’s offspring, Moses pleads, “I pray thee, erase me out of thy book, which thou hast written” (Exodus 32:32). Moses’s cryptic response underscores a hallmark of leadership. Most commentators agree that Moses challenges God saying that if He fails to show mercy to the Israelites, He should erase Moses from the Torah (Pentateuch), effectively volunteering to remove himself from history. According to the 15th-century rabbinic commentator Ovadiah Seforno, the “book” Moses is referring to is the “Book of Life,” and it is Moses’s intention to sacrifice himself and exchange any merit he’s accumulated for the greater good. Both interpretations imply that ethics cannot hold space for ego.

For Emmanual Levinas, God’s unique “face to face” relationship with Moses gives rise to a transcending humanism in which a trace of the divine is present in the face of the individual, obligating us toward one another. Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks identifies the Jewish mystical concept of bittul ha-yesh (the nullification of the self) as a primary marker of leadership and an essential practice in being “open to the Divine, and also the human, Other.” Understandably, Moses’s legacy— of withdrawal and self-negation despite his power and influence— is better suited for backstage. In the theater, humility doesn’t translate well into soliloquy or spectacle. Still, I can’t help but imagine that Shakespeare’s admiration for the Hebrew prophet and poet, is reflected by honoring Moses’s virtuous request to be left out of the “book.”

Although the Hebraic Moses is not summoned to the stage by name, Shakespeare signals the presence of the biblical paradigm through verbal echoes and plot parallels. When Henry VIII seeks a divorce from Katherine after twenty years of marriage, Shakespeare presents the English monarch as both Pharaoh and Moses at once through Katherine’s tempered admonishment: “You’re meek and humble-mouth’d; / You sign your place and calling, in full seeming, / With meekness and humility; but your heart / Is cramm’d with arrogancy, spleen, and pride” (Henry VIII, 2.4.119-122).

Scholars have found facets of Moses as lawgiver and performer of wonders in Shakespeare’s Prospero, the complex protagonist of The Tempest. Other incomplete portraits of Moses based on aspects of his life including a prophecy linked to his birth, being surrendered to the water, and seeking refuge in a foreign land, can be seen in Cymbeline’s Posthumus and Pericles’s Marina, whose name means “woman of the sea,” as Marjorie Garber notes in examining the layers of resonance Shakespeare engineers for his early modern audiences. For Richard Strier, nuanced biblical allusions in The Winter’s Tale to Moses allow Shakespeare to privilege humanistic faith over iconoclasm in the dynamics of the play’s miraculous ending.

In all of these plays, considered the late romances in Shakespeare’s canon, separated families are reunited, exiles are redeemed, and the healing process is initiated through intergenerational storytelling. Pericles requests that those gathered “stay to hear the rest untold” of what has passed (Pericles 5.3.98). Cymbeline gives orders to “publish” news of his family’s homecoming “to all our subjects” (Cymbeline 5.5.579-80). Leontes requests his companions retire “where we may leisurely / Each one demand and answer to his part / Performed in this wide gap of time since first / We were dissevered” (The Winter’s Tale 5.3.189-192). And when his company asks to “hear the story” of his life, Prospero promises to “deliver all” (The Tempest 5.1.371-372). As a playwright with a profound understanding of language— and whose words are continuously invoked to express the stirrings of our hearts and minds— the charge to “speak loudly” (Hamlet 5.2.446) might be seen as Shakespeare’s solution to social distancing and societal trauma. While the biblical archetype does not line up with the heroes of Shakespeare’s romances, this aspect of Moses’s leadership, his oratory ethos, is present.

As an agent and divine interlocutor, Moses speaks and writes a people into existence. When the Israelites are sequestered to their homes during the tenth plague, Moses directs their focus to the stories they will tell and the questions they will answer when the danger has passed: “And when your children ask you, What service is this ye keep? Then ye shall say, It is the sacrifice of the Lord’s Passover, which passed over the houses of the children of Israel in Egypt” (Exodus 12:26-27). Throughout the Exodus and beyond, Moses links speech to deliverance and continuity. After he completes the transcription of the Torah, Moses prepares the people for his death by gathering the elders and officers of the nation “that I may speak these words in their audience” (Deuteronomy 31:28). Though the name of Moses is “erased” from Shakespeare’s canon, his rhetorical presence is felt at some of the most empowering moments of Shakespeare’s works.

For Shakespeare’s original audience, the bible did not simply record the ancestry and engagements of a few specific men and women, but rather mankind’s continuous effort to understand itself in relation to an ever-changing world. Unlike Shakespeare’s foundlings, royals in disguise whose identities are discovered and restored, Moses is not “born great.” Still, as the son of Jewish slaves raised and educated in the Egyptian court and married to a Midianite, Moses’s multiculturalism attracted Renaissance humanists and, I believe, appealed to a playwright heavily invested in the capacity of language and storytelling to forge connections that transcend time and space.

The word Haggadah is Hebrew for “telling,” a distinctly human activity that is not limited to a particular period, people, or belief system. Although we might not be able to be face-to-face with those we love right now, we still have the ability to share stories, exchange memories, and invite others into conversations that transform absence into presence and suffering into healing. My hope for this Passover is that these acts of communication will be enough. Dayenu.

[1] All references to Shakespeare works are from the Folger Digital Texts.

[2] All scriptural references are from the Geneva Bible, which most scholars agree is the bible Shakespeare consulted most often.

[3] One popular explanation for this bewildering omission is that the redactors of the Haggadah exclude Moses lest readers mistakenly come to believe that the Jews’ liberation from slavery, survival in the desert, and formation as a nation were all carried out by Moses rather than through Moses. Another complementary interpretation of Moses’s absence from the Seder script is derived from the last part of the Haggadah which states: “In every generation a person is obligated to see himself as having himself come out of Egyptian bondage.” The observance, or mitzvah, of Passover is fulfilled by recognizing that redemption is not a past event orchestrated by a larger-than-life historical figure, but an ongoing personal endeavor.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.