The notion of Torah u-Madda—that Torah and secular studies can enrich each other—has been a byword in the Modern Orthodox community for decades. Yet some have claimed it is in decline. Lehrhaus is proud to present a symposium grappling with Torah u-Madda: how we got here, the challenges that have arisen, and how its meaning continues to evolve over time.

Symposium Contributions: Editors’ Introduction, Elana Stein Hain, Stuart Halpern, Yisroel Ben-Porat, Sarah Rindner, Erica Brown, Shalom Carmy, Leah Sarna, Tzvi Sinensky, Yaakov Bieler, Moshe Kurtz, Elinatan Kupferberg, Olivia Friedman, Margueya Poupko, Noah Marlowe; Letters to the Editor: 1 | 2

My Personal Connection to Torah u-Madda

I was fortunate to grow up in an environment where Torah study was taken with the utmost seriousness. In middle school I was already introduced to my first piece of Kovetz Shiurim by Rav Elchanan Wasserman, and the classes only became more sophisticated from there. However, I felt that something was missing and that there was an almost purposeful naivete when it came to secular knowledge. One of my high school rebbeim would like to start the day by teaching mussar works. Vayehi ha-yom (one day), we came upon a passage that referred to the dalet yesodot―the four elements: earth, fire, wind, and water. Being the provocateur that I was, I pointed out that the Periodic Table that we learned about in chemistry class had far more than four elements and that the author’s theory was based on an antiquated Greek construct. While I felt that the only place the four elements belonged was in Avatar: The Last Airbender, my rebbe was taken aback by my purported assault on our Jewish faith. He doubled down by claiming: if Hazal said there are four elements, then there are only four elements!

The four elements as portrayed in Avatar: The Last Airbender

The four elements as portrayed in Avatar: The Last Airbender

These kinds of attitudes prompted me to explore Rabbi Norman Lamm’s magnum opus, Torah Umadda. It was nothing short of vindicating to read that one could be fully committed to Torah while also integrating scientific knowledge. As Rabbi Lamm wrote, “Torah Umadda holds that modernity is neither to be uncritically embraced nor utterly shunned nor relentlessly fought, but is to be critically engaged from a mature and responsible Torah vantage.”[1]

In fact, madda (literally: science) could not only be reconciled with our Torah but moreover could be used to enhance it as well. I read the book cover to cover in eleventh grade, and due to my appreciation of it, I arranged to meet Rabbi Lamm at his office at Yeshiva University. I came with a prepared list of questions, and he answered each one patiently with erudition.

Throughout the years, I have contemplated the different models of Torah u-Madda and have reached different conclusions at different stages of my education about its definition and parameters. One generally finds Torah u-Madda invoked in discussing how Halakhah can be synthesized with scientific knowledge and how literary techniques can be used to sharpen our readings of biblical narratives. However, because of its ambiguous definition, some have extended madda to include other pursuits ranging from the appreciation of religious art to hallmarks of contemporary pop culture. Unsurprisingly, the latter category especially requires analysis. Granted, utilizing science to inform us that there are more than four elements constitutes madda, but can knowledge of pop culture be legitimately included in the religious imperative of Torah u-Madda? Can elements of pop culture truly be deemed a worthy use of an observant Jew’s time? I am certainly not the first to the party. Gedolim ve-tovim mimeni (people wiser than me) have already addressed this question. However, I would like to take a less common approach by making the case for what the Science Fiction and Fantasy genre―also known as Geek Culture―specifically brings to the table. Subsequent to discussing the merits of Geek Culture, I will share several caveats unique to the genre, as well as the broader challenges of pop culture writ large.

Objections to Media and Popular Culture

Unlike the Modern Orthodox community,[2] the right-wing yeshiva world believes there is little discussion to be had about benefiting from non-Jewish media, particularly for recreational purposes. R. Moshe Shternbuch, in his Kuntres Ba’alei Teshuvah,[3] addressed the concerns of a young man who was uncomfortable with the fact that his parents own a television. The young man inquired whether it was permissible for him to destroy the TV remote to prevent his parents from committing this terrible sin. The most striking part of the responsum is not what R. Shternbuch wrote in his answer but what he deliberately chose not to reckon with. Instead of beginning the responsum by deliberating if and when television would be religiously problematic, he assumes from the outset that it is unequivocally prohibited:

Behold, the prohibition to watch a television is very severe and is an avizrayhu de-arayot (an accessory prohibition to sexual sins), because as a result of watching this impure vessel, it will cause him to be drawn after them. A person is certainly obligated to distance himself from watching television, and to use numerous methods to do so. This is really within the category of pesik reishei (a certain consequence), in that living in a house with a television makes those who watch it impure, God forbid.

R. Shternbuch proceeds to find the most halakhically appropriate way for this young man to save his parents from Divine punishment for watching television. It is clear that he is not willing to entertain even the possibility that some television programs might be permissible.

An advertisement for a major anti-internet/anti-media conference at Citi Field in 2012.

Lest one write off R. Shternbuch as an outlier on this issue, note that R. Moshe Feinstein operated with the same premise when asked whether a Jewish man who goes to the movies should first remove his head covering. R. Feinstein ruled that one should not add one sin on top of another, first by going to the movies, and secondly by removing one’s head covering.[4]

The concern, especially for the licentious nature of secular media, led R. Asher Weiss[5] to invoke et la’asot la-Hashem heferu toratekha[6] to justify turning biblical verses into Jewish pop music. He argues that despite the fact that the Talmud[7] forbade adapting the Song of Songs (and arguably other parts of Tanakh) into mediums for entertainment, our refusal to permit the adaptation of biblical verses into pop music would run the risk of many Jews turning to non-Jewish avenues for entertainment, which are fraught with illicit content.

While media was at one time more innocuous, the passe nature in which graphic sexuality is on display should disturb anyone with basic Torah sensitivities. A PG-13 film today can easily contain scenes which, from a halakhic standpoint, are no different than viewing bona fide pornography.[8] The quality of television and media has devolved to such a great degree that even certain Modern Orthodox rabbinic figures have felt the necessity to put their foot down. Notably, R. Yitzchak Blau decries:

We could imagine saying to a Haredi interlocutor: “Modern Orthodoxy’s advantage is our ability to cull wisdom found in Bradley’s philosophy and Yeats’ poetry.” Could we imagine saying: “Modern Orthodoxy’s advantage is our ability to watch Friends and Desperate Housewives”? The time has come for a widespread communal effort to minimize intake of the vacuous elements of popular culture … Modern Orthodox Jews do not only watch enough TV and movies to regain their strength, they spend numerous hours watching TV as an end in itself, often failing to make discriminating judgments about which shows to watch.[9]

In addition to sexual content, R. Blau challenges us to take an honest look at ourselves and ask if indulging in entertainment media is truly a productive use of our time. The concern for bittul Torah, neglecting Torah, is frequently invoked by those who oppose secular media. Even if one finds an appropriate show to watch or a book to read, perhaps one should be allocating more of that time to religious pursuits. This behooves us to ask: since our time is axiomatically limited, what value does Geek Culture bring to the table that it ought to occupy a slot on our limited schedules?[10]

Geek Culture as a Conduit for Exploring Ethics and Morality

Yu-Gi-Oh!, Magic: the Gathering, Gloomhaven, Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings―the common theme between these words is the Science Fiction & Fantasy genre, or Geek Culture. I loved growing up on this genre and have continued with it to this day. When I studied at my gap-year program, Yeshivat Sha’alvim, it was almost the same group of students who attended the voluntary Early Prophets class that also gathered for Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) during our break time. And it’s no surprise―they both contain compelling narratives full of war, adventure, and religious intrigue.

When I subsequently attended Yeshiva College, we studied the third chapter of masekhet Sanhedrin,[11] which lists those who are disqualified from giving testimony in court. Upon reaching the case of the mesahek be-kubya, one who plays with dice, my rebbe facetiously asked, “So nu, anyone got some dice on them?” To everyone’s surprise, I whipped out my pack of D&D gaming dice and passed them up to the front of the lecture hall. He poured the contents onto his desk and tried to make sense of this apparent new devilry. Upon seeing the vast assortment of paraphernalia, which, of course, included the iconic twenty-sided die, my rebbe exclaimed, “Shaketz teshaktzenu ve-ta’ev titavenu!”[12]

Typical dice used to play Dungeons & Dragons and other Fantasy tabletop role-playing games.

But in all seriousness, while Fantasy and Science Fiction (SciFi/Fantasy) have their fair share of questionable material (particularly Japanese Anime), there are many appropriate expressions of the genre that have enabled serious reflection and discussion about theology and the human condition.[13] This is especially salient when the genre explicitly and implicitly addresses the philosophical questions of morality.

Certainly, we cannot discuss Fantasy without invoking J. R. R. Tolkien, the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien has many lessons to share. For one, he conveys how it is often the smaller and seemingly insignificant things that can change the course of history. This can be observed in the heroism of the hobbits as well as in the disproportionate power of the One Ring. As Boromir remarked, “Is it not a strange fate that we should suffer so much fear and doubt for so small a thing?” These themes echo the David versus Goliath nature of the Jewish people throughout history from the times of the Maccabees to modern-day Israel. In his article, “The Secret Jews of the Hobbit,” Rabbi Meir Soloveichik argues that the Dwarves of Tolkien’s Middle Earth were intended to reflect the Jewish people’s struggles of exile and their journey to reclaim their homeland. (He also notes the Dwarves’ obsession with gold—but he makes the case for why Tolkien was certainly not antisemitic.) While an indescribable amount of credit is due to Tolkien, there are some underlying motifs that are potentially incompatible with Judaism.

A quintessential portrayal of Good versus Evil in popular Geek Culture.

A quintessential portrayal of Good versus Evil in popular Geek Culture.

For instance, the Torah and rabbinic tradition[14] reject the belief in cosmic dualism. As God in Isaiah 45:7 proclaims: “I form the light, and create darkness; I make peace, and create evil; I am the Lord, that doeth all these things.” While Tolkien in The Silmarillion acknowledges an all-powerful creator, Eru Ilúvatar, the plotline of The Lord of the Rings puts the forces of Good and Evil on equal footing and portrays the fate of the world as being contingent on which one triumphs. This point is noted by Dr. Michael Weingrad, who writes:

In general, Judaism is much warier about the temptation of dualism than is Christianity, and undercuts the power and significance of any rivals to God, whether Leviathan, angel, or, especially for our purposes, devil. Fantasy literature is often based around conflict with a powerful evil force—Tolkien’s Morgoth and Sauron and Lewis’s Jadis and the White Witch are clear examples—and Christianity offers a far more developed tradition of evil as a supernatural, external, autonomous force than does Judaism, whose Satan (or Samael or Lilith or Ashmedai) are limited in their power and usually rather obedient to God’s wishes.

But there is also fantasy that succumbs far less to the charge of dualism. In particular, George R. R. Martin, in his exceedingly popular book series, A Song of Ice and Fire, addresses questions of Good and Evil through numerous morally gray characters. Unlike Tolkien, who created a generic conflict between the good people of Middle Earth and a patently evil Dark Lord, Martin deliberately crafts ambiguity and nuance to more accurately capture the human condition. In a New York Times interview, Martin explained that he incorporated the darkest and most unspeakable acts of human wickedness like rape and torture into his books because, “To omit them from a narrative centered on war and power would have been fundamentally false and dishonest… and would have undermined one of the themes of the books: that the true horrors of human history derive not from orcs and Dark Lords, but from ourselves.”

Martin’s subversive take on Fantasy storytelling set the bar for other modern authors of the genre. One of the lead protagonists in Brent Week’s Lightbringer series, Gavin Guile, is both charismatic and self-serving. Similarly, Joe Abercrombie, a pioneer of the Grimdark Fantasy subgenre, deliberately writes an entire cast of flawed and sometimes downright evil protagonists. A notable example is Sand dan Glokta, who nonchalantly tortures prisoners in his capacity as a member of the King’s Inquisition. By making “protagonists” amoral or immoral, it beckons the reader to ask: what actually makes someone the “good guy”? Such storytelling decisions make us think more critically about why we accept certain individuals as good: is it because the state or the media tell us so, or do we analyze a person’s merits based on Torah values?

Let us shift from Fantasy to Science Fiction by taking a look at Magneto, the Jewish, morally gray, arch-villain of the X-Men movie franchise. At first, one might be tempted to brand Magneto as a one-dimensional antagonist who simply wants to kill all non-mutant human beings. However, one cannot help but feel sympathy for him upon witnessing the tragic scene where he is pulled away from his mother in the Nazi concentration camps and fails to use his newfound powers to save her. Years down the line, when human governments posed a threat to his fellow mutants, he understandably stood up against the threat with force rather than pursuing pacifism and diplomacy, like the protagonist Professor Charles Xavier. Magento’s traumatic backstory forged within him the resolve to say “never again” by resolving to take up arms—an attitude akin to what post-Holocaust early Zionists espoused.[15]

A juxtaposition of the X-Men franchise antagonist, Magneto, portraying his tragic Holocaust backstory.

There is also much to learn about morality from video and tabletop gaming. The 2003 video game blockbuster, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (KOTOR), not only provided one of the best known plot twists in video game history―it also helped revolutionize a morality system. Throughout the game the player makes critical choices to decide between the Light Side or Dark Side. These choices ultimately affect both the player’s moral standing as well as their arsenal of abilities when using the “force.” A given player might not have a strong preference for being evil, but if that is what it takes for him to wield a feat like Force Lighting, you can bet he will kill every NPC (non-player character) in the game if need be. Thus, KOTOR (as well as its later iteration, The Old Republic massive-multiplayer-online-role-playing-game, or MMORPG for short) gave players a sense of what it means to be tempted by power and to what extent they are willing to either resist or succumb to their evil inclination.

KOTOR, however, was not the first game in the genre to explore morality in gaming. D&D can be credited with popularizing the alignment system which categorizes characters on a scale from Good to Evil and Lawful to Chaotic. During my D&D days I would often argue with the Dungeon Master (DM) and claim that my character was right to kill an unarmed enemy who was too dangerous to be left alive.[16] While these discussions often derailed the actual gameplay, it produced a robust debate about the definition of good and evil. For instance, I would always cite a case-in-point about how Batman refusing to kill villains like the Joker was actually an act of evil since they would eventually break out of Arkham Asylum and murder more innocent victims. My argument was in line with the statement in Kohelet Rabbah (7:16): “All those who are merciful in a place of cruelty, in the end they are being cruel in a place of mercy.”[17]

The classic Dungeons & Dragons moral alignment table with recognized movie characters for reference.

Indeed, one of the most gratifying outcomes of discussing SciFi/Fantasy with others is when it serves as the basis for a halakhic debate. To briefly list a few more examples: Does Spock’s assertion in Star Trek, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” comport with the rabbinic conception of why it was permissible for a city to hand over one individual, Sheba ben Bikhri, in order to save the rest of its inhabitants?[18] The Twilight Zone featured an episode entitled “Cradle of Darkness” in which the protagonist goes back in time to kill baby Hitler—would baby Hitler be nidon al shem sofo (judged based on his future outcome) like the Rebellious Son,[19] or do we judge someone ba-asher hu sham (as they are in the present), like Yishmael?[20] Does the topic of whether Eshet Eliyahu (Eliyahu’s wife) remained married to Eliyahu even after he ascended to heaven in a fiery chariot provide insight into what happens after someone’s spouse returns post-Thanos snap?[21] And of course, there are the more oddly obscure questions: Does ordering a Solar Beam attack in Pokémon constitute bishul be-shabbat (cooking on Shabbat)? Can a man use the One Ring of Power from The Lord of the Rings to betroth a woman? Granted, these ideas may sound odd to the uninitiated ear; however, they have all managed to spark serious halakhic debates and prompted otherwise uninterested parties to engage in Torah discourse.

Several Concluding Caveats

At this point, I have demonstrated how deeply I enjoy SciFi/Fantasy and how I have benefited from Geek Culture both intellectually and emotionally. Still, I have a number of general reservations about how these interests interact with Torah study and general religious life. The first two caveats relate to the role of the pedagogue, and the latter two apply to any individual.

(1) I once attended a shul where the rabbi started his sermon every week with a sports analogy. I eventually got so put off by this that I started going to a different minyan. What bothered me was twofold: Firstly, I am a SciFi/Fantasy Geek, so I couldn’t care less for what he was talking about.[22]

Second, if a rabbi or Judaics teacher always needs to rely on a sports or pop culture mashal, many of the listeners may find it patronizing. While, on the one hand, this practice has the potential to pique the audience’s interest, it also has the Achilles heel of indicating that either the primary material is not sufficiently interesting or that the audience lacks the sophistication to appreciate what is being shared with them. When someone tries too hard to be relatable, the listeners often notice.

That being said, I will often drop SciFi/Fantasy references in my classes because it entertains me and perhaps also every one out of twenty listeners, should I be so fortunate. While Geek Culture is experiencing a renaissance, it is still not mainstream in my social environs. I wish that more people understood my references, but I am consoled by the fact that I can still incorporate my “Easter Eggs” without it becoming a contrived attempt to earn popularity points. For me, it is just a nice way to give a nod to my fellow Geeks and feel a sense of solidarity with my cultural minority.

(2) In addition to potentially patronizing one’s audience, the overuse of pop culture references cheapens the Torah that it is supposedly meant to enhance. As a mentor once told me, you need to know when you are being “mekadesh the hol” and when you are just being “mehalel the kodesh.” While Geek and general popular culture has the power to bring people in, it also runs the risk of degrading the topic at hand. Are the Divine words of the Almighty Eternal God so unappealing that they need to be cheaply packaged with TV and movie lines?

(3) Moving beyond pedagogy, Rabbi Jeremy Wieder conveyed the following in his relatively viral 2017 critique of Game of Thrones:[23] “The famous passage in Eikhah Rabbah,[24] ‘im yomar lekha adam yesh hokhmah ba-goyim, ta’amen…’―if a person tells you that there is hokhmah amongst the nations of the world you should believe it―that’s a very important value, but let me emphasize: this is not hokhmah.”

Assuming we can plausibly discern the okhel from the pesolet (the valuable from the waste) and use Geek Culture to provide opportunities to facilitate Torah study, all it really amounts to at best is a hekhsher mitzvah, or a preparatory activity for Torah study.[25] It is challenging to classify it as a true hokhmah to the extent that pursuing it as its own endeavor would not constitute bittul Torah, unlike areas such as medicine. I am a major proponent of all things Geeky, but I try not to delude myself into thinking that when I play Call of Duty or read Harry Potter that I am being mekayem some kind of mitzvat aseh (fulfilling a positive commandment). Rather, I listen, watch, play, and read what I do because I enjoy it―it’s my preferred use of necessary leisure time. Agav (incidentally), once I am doing that, I am open to being inspired or intellectually captivated by a theme that in some indirect way might enhance my Torah study and service of God. But I try to keep myself honest by endeavoring not to conflate my recreation with my religion.

When I was growing up in the yeshiva world, I made it a point to advocate for incorporating and appreciating key elements of madda. However, the Modern Orthodox world does madda and secular culture quite well enough already. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks wrote in his afterword to Rabbi Lamm’s Torah Umadda, “If we are to revive the failing pulse of Jewish existence in time―the dialogue between covenant and circumstance, the word of God and the existential situation of the Jewish people―it is Torah rather more than madda which needs persuasive advocacy.”[26]

Moreover, Torah u-Madda has colloquially devolved into the Tikkun Olam of Modern Orthodoxy: a motto so flexible and amorphous that it has regrettably become next to meaningless. And like Tikkun Olam, since Torah u-Madda has become our movement’s accepted mantra, anything that can conceivably be classified under madda is ipso facto regarded as a sacrosanct religious pursuit.

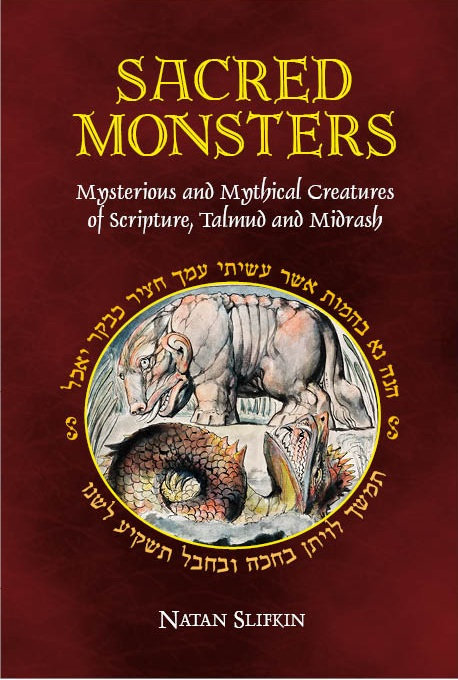

(4) As other Jewish Fantasy Geeks might experience, there is an inclination to fuse the two epic worlds of Torah and Geekdom. I remember many years ago I excitedly picked up R. Natan Slifkin’s well-researched Sacred Monsters only to be disappointed that his work only furthered the connection between Judaism, Fantasy, and the natural world. I picked up the book with an image of an awesome and mythical creature known as the Leviathan, only to have it reduced to a mundane whale. The creatures discussed suddenly seemed less sacred and less monstrous at the same time.

Once upon a time, I too had sought to fuse Judaism and Fantasy. I made a Dungeons & Dragons campaign base in the Book of Kings and pondered why R. Shimon bar Yohai could not use his powers to incinerate his Roman pursuers like Cyclops in X-Men.[27] Yet, as my own theology developed, I eventually espoused the aforementioned rationalist perspective on the Bible and rabbinic literature, which made it harder to read the fantastical into Jewish texts. In fact, R. Yitzchak Blau argues that attempting to mine Torah literature for fantastical content is a fallacious endeavor: “If we search the gemara for demon stories as we would eagerly anticipate the next Superman comic book, then we have missed the point. The gemara is not an action and adventure story, but a work of religious and ethical instruction.”[28]

With this in mind, I have concluded that perhaps I need not synthesize my religion with my personal interests and pastimes. On occasion, one will find epic moments in Tanakh, such as when Eliyahu calls down a fire from heaven, but for the most part, one will not find the same breathtaking supernatural feats that the Fantasy genre provides.

Combining Torah and popular culture can be entertaining, and on occasion, even enlightening. But for the most part, it remains nothing more than a hobby and general area of interest for me. Thus, I learn Torah and I happen to engage in Geek Culture. When something in Geek Culture gets me to think seriously about a moral issue or provides me with a moment of inspiration, I am thrilled.

Sacred Monsters by R. Natan Slifkin

Nonetheless, the religious pursuit of Torah and the non-Jewish genre of Geek Culture need not intersect, just as I believe for the humanities writ large.

I am happy to live a life of Torah and Geekdom, but I am not convinced that it necessarily needs to be Torah u-Geekdom.

[1] Norman Lamm, Torah Umadda (Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 1990), 48.

[2] See for example www.koshermovies.com, in which R. Herbert J. Cohen, a Modern Orthodox rabbi, selects religiously appropriate movies and expounds on the lessons that they have to offer.

[3] Moshe Shternbuch, Responsa Teshuvot Ve-Hanhagot (1:368).

[4] See R. Elchanan Wasserman’s treatment of theaters and other gentile gatherings in Kovetz Maamarim (90, 92-93). See also Rabbi Chaim David HaLevi in his Responsa Aseh Lekha Rav (1:63 and 4:47). Rabbi David Stav provides a useful summary of the topic in his Sefer Bein Ha-Zmanim (202-203).

[5] R. Asher Weiss, Responsa Minhat Asher (2:44).

[6] Lit.: “It is time for the Lord to work; they have made void Thy law” (Psalms 119:126). This principle is essentially the nuclear option of Rabbinic Judaism. When Judaism itself is at risk and there is no other recourse, this principle allows the Rabbis to violate a Biblical prohibition to preserve the religion. An iconic example is when the sages declared that the Oral Torah should be recorded in writing to avoid losing the tradition entirely (Gittin 60b).

[7] Sanhedrin 101a.

[8] From a religious standpoint, viewing a sex scene in a movie more than exceeds the threshold of constituting forbidden conduct. As the Talmud in Berakhot 24a, codified in the Shulhan Arukh (E.H. 21:1), states: “Anyone who gazes upon a woman’s little finger [for sensual pleasure] is considered as if he gazed upon her naked genitals.” Kal va-homer (a fortiori), the multitude of movies today which expose much more than a finger to evoke sensual thoughts would certainly be forbidden to watch.

[9] Yitzchak Blau, “Contemporary Challenges for Modern Orthodoxy,” Orthodox Forum (303-305).

[10] For further reading, see Norman Lamm, “A Jewish Ethic of Leisure,” in Faith and Doubt: Studies in Traditional Jewish Thought (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1971), 184-207.

[11] Sanhedrin 24b.

[12] “Neither shalt thou bring an abomination into thine house, lest thou be a cursed thing like it: but thou shalt utterly detest it, and thou shalt utterly abhor it; for it is a cursed thing” (Deuteronomy 7:26).

[13] My general rule is that if the film or show has at least a mi’ut ha-matzu’i of problematic material, then it should be avoided, even if one attempts to skip the problematic material (certainly, if it’s parutz merubah al ha’omed). In standard parlance, if the subject in question is comprised of more than 10% problematic material, my rule of thumb would be to avoid it entirely.

[14] See, for example, Berakhot 23b and Kli Yakar’s exposition of the verse in Deuteronomy 32:39: “See now that I, even I, am He, and there is no god with Me; I kill, and I make alive; I have wounded, and I heal; and there is none that can deliver out of My hand.”

[15] The recent animated Netflix adaptation of Castlevania serves as another poignant example of an antagonist whose motives evoke sympathy. The pilot episode shows the Catholic Church burning Count Dracula’s wife at the stake which drives him toward madness and bringing vengeance upon the human race. While it goes without saying that genocide is certainly not justifiable, the creators of the show skillfully managed to give us a nuanced villian with a tragically understandable motivation, rather than the typical one-dimentional bad guy who is evil for its own sake.

[16] This is also akin to Anakin killing Count Dooku in Star Wars Episode III: The Revenge of the Sith.

[17] Naturally, we also debated whether it was religiously appropriate for someone to play a cleric class, thus requiring him to worship one of the deities from the D&D pantheon.

[18] See II Samuel 20; y. Terumot 8:4; Mishneh Torah (Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah 5:5); and recent rulings by Chazon Ish (Hilkhot Avodat Kokhavim no. 69) and Responsa Tzitz Eliezer (15:70). A friend and colleague of mine, R. David Tribuch, pointed out that the boat dilemma at the end of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight has also stimulated similar debates.

[19] See Deuteronomy 21:18-21.

[20] See Genesis 21:17 and Rosh Hashanah 16b: “And Rabbi Yitzhak said: A man is judged only according to his deeds at the time of his judgment, as it is stated: ‘For God has heard the voice of the lad where he is'” (Genesis 21:17).

[21] R. Elchanan Wasserman (Kovetz Shiurim Vol. 2, 52-53) explores whether Eliyahu’s wife remained halakhically married to him since he did not die but left this world through a supernatural means. This could provide insight into whether those who temporarily disappeared due to the supernatural powers of the Infinity Gauntlet would have been considered to have died and subsequently resurrected.

[22] I recall in high school it was essentially minhag yisrael for the rebbeim to exhort their students to avoid watching the Superbowl by making statements like, “Why do you want to watch a bunch of beheimos fighting to bring a ball to the other side of the field? Go learn night seder instead!” Ironically, I actually enjoyed hearing this. Well, perhaps not for the intended reason, but it was certainly vindicating to hear a few disparaging comments about professional sports made by a religious authority figure. Of course, they would have given a similar critique against Geek Culture, but that was simply not on their radar.

[23] A friend of mine brought to my attention that there were a few “frum” Christians who selflessly volunteered to be the Nachshon ben Aminadavs and produced a version of the show which removes all of the sexually explicit content. This is akin to the pseudo-yeshivish acapella groups that adapt licentious pop music into a religiously acceptable format for Sefira and the Three Weeks. It remains unclear to me, however, who issued them the heter to watch or listen to such material in the first place.

[24] Eikhah Rabbah 2:13.

[25] See Lamm, Torah Umadda, 131-134.

[26] Lamm, Torah Umadda, 218.

[27] See Shabbat 33b.

[28] Yitzchak Blau, Fresh Fruit and Vintage Wine (Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Publishing House, 2009), 181.

To see the rest of the symposium, click here.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.