Steven Bayme

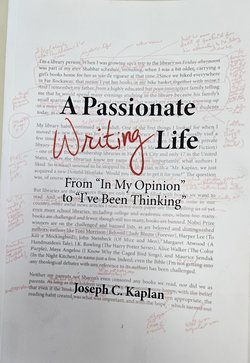

Review of Joseph Kaplan, A Passionate Writing Life ( Teaneck, NJ: The Judaica House, 2023)

Reviewing a volume some years back on Modern Orthodoxy and sexual ethics, I concluded the review by noting that the authors―as do other Modern Orthodox rabbis and intellectuals―fall into the trap of leading readers up to the edge of the water but then decline to get their feet wet. Arguable or not, the allegation clearly does not apply to Joseph Kaplan, a retired attorney and Modern Orthodox intellectual and lay leader, who boldly dives into the thicket of current Modern Orthodox debates and dilemmas, controversial though they may be.

This book comprises a selected anthology of Kaplan’s writings spanning well over half a century. Over the decades, these have appeared in publications as diverse as the journal Sh’ma, the Jewish Standard, The New York Times, and even Yeshiva University’s undergraduate newspaper, The Commentator. The volume presents the reader both with a set of period pieces depicting Modern Orthodoxy in Kaplan’s early years and a cogent commentary on the more recent and contemporary Orthodox scene.

Kaplan’s range of topics is wide and diverse. The columns and essays traverse seamlessly from Jewish law to family experiences as well as popular culture (including television and sports), tributes to leading personalities, beautiful obits of departed loved ones, and touching personal vignettes, including a remarkable portrait of an East European director of RIETS at YU who―like Kaplan himself―adored Woody Guthrie’s music. An introduction, italicized for easy identification, precedes many of the essays, contextualizing the piece historically and its intended purpose. An afterword, similarly italicized, in many cases usefully updates the reader as to where the issue under discussion stands today.

Of particular interest to Kaplan are the challenges to contemporary Modern Orthodoxy and its quest for a distinctive identity in contrast both to the Haredi world and to the liberal religious movements. Clearly at home across the Jewish denominational spectrum, Kaplan addresses with sensitivity and respect those with whom he disagrees on both his Right and Left flanks. For example, he offers glowing encomia to relatively right-wing YU roshei yeshiva, such as R. Hershel Schachter, R. Yehuda Parnes, and R. Mordechai Willig, notwithstanding pointed disagreements with their respective hashkafot disparaging Modern Orthodoxy and Open Orthodoxy.

His analysis opens with an effort to define Modern Orthodoxy, distinguishing between those whose values remain generally in sync with Haredi Orthodoxy but who harness aspects of modernity—e.g., computer technology so as to access responsa literature—and what may be termed “Modern Orthodoxy veritas,” which internalizes modern culture as a source of values rather than purely as an instrumentality. Similarly, he contrasts Modern Orthodoxy with the more inclusive yet more vague “Centrist Orthodoxy,” a fluid and undefined mid-point somewhere between the Orthodox Right and Left featuring a mood informed by modern culture but within sharply defined parameters. By contrast, Kaplan champions a distinctive synthesis of Torah and modern culture that explores the ties and tensions between two value systems while upholding the primacy of Torah. His case is perhaps strengthened by Dr. Norman Lamm, z”l, who admitted toward the close of his presidency at Yeshiva University that he may well have erred in seeking to replace the nomenclature “Modern Orthodoxy” with the fuzzier and more ambiguous “Centrist Orthodoxy.”[1]

Thus, Kaplan challenges some of the rightward drift in contemporary Modern Orthodoxy. He bemoans gender segregation at some wedding receptions and semahot in the Modern Orthodox community, a trend seemingly at odds with resolving the universally lamented “shidduch crisis.” Conversely, he details the struggle to legitimize women’s tefillah groups, a cause he and his wife championed successfully in both Manhattan and Teaneck in the face of vigorous opposition from noted roshei yeshiva.

A distinguished attorney by trade, Kaplan capably elucidates some of the most fascinating court cases related to Jewish law and Orthodox institutions. Among these he unpacks: (1) the 1980s yarmulke case of a U.S. Air Force captain denied the right to wear his kippah on duty and who subsequently brought his case before the U.S. Supreme Court; (2) the 1970s case of Yeshiva University declining to recognize a faculty union as a bargaining unit, in which the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote, rejected the faculty demand for unionization and upheld YU’s position; and (3) the “Get Bill” legislation in New York State enabling the secular state court to incentivize a Jewish bill of divorce in the case of a recalcitrant husband refusing to issue a get and leaving his spouse incapable of remarriage in accordance with Jewish law.

In each of these cases, Kaplan adroitly unpacks the issues under contention. The yarmulke case entailed conflict between the military ethos of conformity with time-honored Jewish custom. The YU case addressed whether university faculty were staff and therefore entitled to unionize, or management who determined their own teaching hours and course requirements and therefore not entitled to unionize. With respect to the Get Bill, Kaplan argues—correctly, in my opinion—that the secular state should not be involved in solving Jewish halakhic problems. If Jewish divorce law imposes hardship on the divorced female spouse—as it clearly sometimes does when women become agunot—rabbis and scholars need to resolve this issue internally and not depend on state intervention, which easily could lead to further state intervention in Jewish religious practice and regulation of internal Jewish communal affairs.

The NLRB v. Yeshiva University case was perhaps the most complicated of these judicial decisions, evidenced by the 5-4 vote. Kaplan invokes his undergraduate days, when students virtually unanimously perceived the college administration as possessing decision-making authority while faculty had to be content with substandard salaries and poor working conditions. As a member of YU’s full-time faculty while the case was under review, I followed this debate carefully. Kaplan’s perception of where authority lay is largely correct. But at the time, I also noted that the putative union heavily favored the needs of senior faculty at the expense of junior faculty who were barely eking out a living, if that. Whether a union at YU would have succeeded in securing adequate wages and working conditions for a dedicated yet largely demoralized faculty remains questionable. For its part, the Court—impressed that YU faculty recently had become actively involved in hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions—ruled that faculty indeed were “management” and could not unionize.

Kaplan has much to say about a range of other issues dividing Orthodoxy, and everyone will find something to agree with and to disagree with. He lauds non-Orthodox rabbis and leaders, whose wisdom he cherishes and from whom he learned greatly. Similarly, he mounts an eloquent defense of women as Orthodox rabbis, a much-contested issue between “Open” and “Centrist” Orthodoxy. To be sure, there are notable omissions. Biblical criticism receives no mention, while partnership minyanim merit only a passing notice that he attended one at least on one occasion. Similarly, he references the late Meir Kahane only as a young Hebrew teacher, eschewing all mention of the latter’s odious ideology, which unfortunately appears in greater vogue today in some contemporary religious Zionist circles in Israel. Conversely, Kaplan teases the readership with a favorable reference to “Post-Orthodox” teachers but neglects to tell his readers who they are, what they teach, and what they believe in.

So what does one make of this witty and engaging anthology? The volume provides a lucid albeit partisan guide through the warp and woof of contemporary Modern Orthodox debates and controversies. Always respectful of those with whom he disagrees, even most strongly, Kaplan models a civil discourse all too often lacking in the Orthodox world, to say nothing of a polarized American society generally. Although the volume contains unnecessary repetitions, programmatically it serves both as an excellent entry point into the thicket of contemporary Orthodox discourse and as take-off point for intelligent and thoughtful discussion as to Orthodoxy’s future directions.

But the answers to the larger questions of synthesis, coexistence, and conflict between the value systems of Torah and modern culture remain elusive. Clearly the study of Torah benefits when it imbibes the teachings of philosophy, geography, literature, even psychology. History, by contrast, particularly ancient history, often appears in conflict with the narrative of the Torah. Conversely, modernity has much to learn from the study of Torah about human nature, justice, even political theory. But what happens when the two cultures stand in conflict with one another rather than coexist harmoniously? Does one jettison knowledge of ancient history when studying Tanakh? Virtually everything that occurs within Israeli Orthodoxy has repercussions and implications for American Orthodoxy. Yet Kaplan neglects to draw these parallels. Does religious Zionism (Torah Va-Avodah) connote creation of a Jewish democratic state on principles of Torah? Or has religious Zionism been hijacked by Gush Emunim, to say nothing of the extremism of Smotrich and Ben Gvir? Perhaps most importantly, has Modern Orthodoxy nurtured the intellectual leadership so necessary both for itself and the Jewish people writ large, or has it abdicated such leadership in favor of gedolim often removed from the needs of klal yisrael and who aspire to create “learner earners” rather than men and women who embody synthesis? These questions—whether applied to critical study of Jewish text, political wisdom, or contemporary ethics—all warrant extensive consideration. Joseph Kaplan points the way, but his book is not the endpoint of such deliberations.

Kaplan’s vigorous advocacy for a truly Modern Orthodoxy will meet with both resonance and opposition. But no one interested in Orthodoxy, its place on the Jewish scene, and its future ought to ignore this critically important work.

[1] Norman Lamm, Seventy Faces: Articles of Faith, vol. 1 (Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, 2002), 2.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.