Aron Wander

“Do not write a history except of your wounds. Do not write a history except that of your exile.” – Mahmoud Darwish[1]

“Sparks of divinity… have been trapped by the forces of evil, and that is the purpose of the Jewish people’s exile across many lands and to the ends of the earth.” – R. Hayyim David Azulai[2]

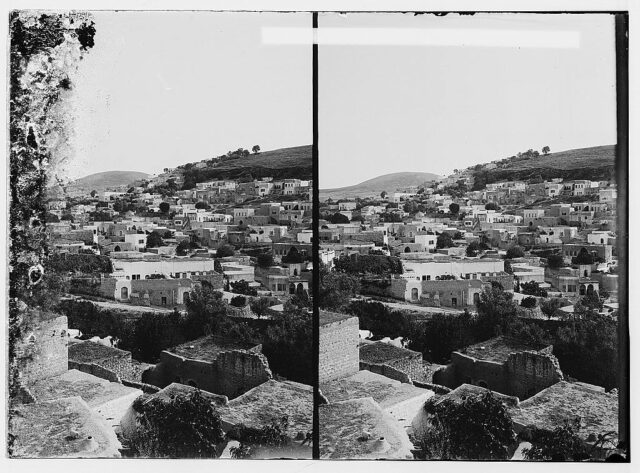

Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin’s Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra: Tzefat Ve-HaTarbut Ha-Tzionit (Biblical Consciousness, Mishnah Consciousness: Safed and Zionist Culture) is an act of recollection. At the center of the book stands the 16th-century Kabbalistic community of Safed, with its poets, mystics, hermits, and halakhists. In Raz-Krakotzkin’s telling, historic Safed offers an alternative vision of Jewish living and flourishing in the land of Israel to that historically proposed by Zionism, shedding critical light on the cultural, moral, and political choices that Zionism has made.

The Kabbalists of Safed, Raz-Krakotzkin argues, saw their primary mission as connecting to and reenacting the experience of galut (exile). For them, galut did not merely signify the Jews’ absence from or lack of sovereignty in Eretz Yisrael. Rather, they saw Jews’ particular, physical galut as part of a broader web of “exiles”: the broken state of the world at large, and even a certain brokenness within God Himself.

The Kabbalists of Safed believed that the particular redemption of the Jewish people could only come about by way of a redemption of the entire world and of God, too. Their rituals―visiting the graves of deceased masters, mourning God’s brokenness, wandering the land in order to be closer to the Shekhinah (the “exiled” part of God), reciting mystical formulations―were all designed to allow them to experience the totality of those interwoven exiles.

Ironically, for the Kabbalists of Safed, to be in Eretz Yisrael was the most potent way of experiencing exile. “Going up to Eretz Yisrael,” writes Raz-Krakotzkin, “was not conceived of as a return to the homeland but rather as a way of connecting to galut and the experience of galut.”[3] He adds that, from their perspective, “settling in Eretz Yisrael grants an experience of redemption… specifically because it allows one to experience the fullness of galut.”[4] Deepening their consciousness of exile, paradoxically, had a redemptive function: the yearning for redemption provoked by feeling the full weight of galut was itself a key part of bringing about redemption. As Raz-Krakotzkin explains, “Galut and redemption do not cancel each other out [for the Kabbalists]. Rather, they are interwoven such that galut is a precondition for redemption.”[5]

Raz-Krakotzkin emphasizes how Safedian ritual and culture drew from its Ottoman milieu. Though the community included both Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews, its members participated in a complex cultural exchange with surrounding Islamic communities in which ritual, law, mysticism, and poetry were freely blended. It was this fusion that laid the basis for Safed’s rich ritual and cultural world: halakhic practices were invested with mystical and redemptive significance while poets crafted liturgy describing erotic longing for the Shekhinah.

Early political Zionism, by contrast, grounded itself firmly in Europe. Eschewing the interwoven cultural tradition suggested by Safed, Zionism sought to sever Jewishness from those aspects it considered “eastern” and therefore outmoded, particularly Jewish law and mysticism. Galut, too, was cut off from its rich symbolic context. For early Zionism, Raz-Krakotzkin argues, galut was a mere political status to be abolished by building a Jewish polity in Eretz Yisrael, nevermind the exile of the rest of the world or the cosmos. The idea of deepening one’s consciousness of galut was anathema to Zionism―galut was something to be overcome, not reenacted. If the Kabbalists of Safed saw exile as the foundation of Jewishness, many leading Zionists saw the 2,000-year interlude between the Roman exile and their own project as an embarrassing and unfortunate episode to be excised from their history.

Underlying the differences in the way the early Zionists and the Kabbalists conceived of galut were two divergent relationships to Jewish text and history. The Kabbalists of Safed saw themselves as reenacting the period of the Mishnah, mediated through the Zohar (which claims to be from the Mishnaic period). Just as the rabbinic fellowship of the Zohar wandered around the land of Israel searching for the Shekhinah, they too saw their task as building a dedicated cohort whose wanderings and theurgic actions would repair the rift within God.

For the Zionists, the Tanakh, rather than the Mishnah, was their primary text. It offered a model of conquest and power: the forceful elimination of galut rather than its accentuation. with the local Palestinian population either absent or―during the 1948 war―sometimes mapped onto the Canaanite nations.[6] Simultaneously, for Zionists, reading the Tanakh unmediated by the vast traditional textual corpus was a way of divorcing Jewishness from the rabbinic (and exilic) tradition. The inspiration for such a move came, ironically, from Protestantism, which advocated for engaging the Bible directly without intermediaries. Accordingly, as Raz-Krakotzkin puts it, “The return to the Tanakh [was]… also a return to the West.”[7]

Raz-Krakotzkin’s critique takes place on the levels of both history and historiography. Safed was one of the key cultural centers of Judaism. Its residents included Rabbi Yosef Karo, who authored the authoritative Jewish legal guide, the Shulkhan Arukh; Rabbi Moshe Cordovero and Rabbi Yitzhak Luria, each of whom founded new Kabbalistic systems that soon became foundational throughout the Jewish world (though the latter eventually eclipsed the former);[8] and R. Shlomo Alkabetz, best known for writing Lekhah Dodi. But despite its central role in Jewish history, Raz-Krakotzkin notes that Safed has largely been ignored in Zionist curricula and histories. And even though some Zionist historians have addressed Safed, they have done so in implicitly orientalist terms, cutting it off from its Ottoman background and assessing its contributions to law, Kabbalah, and poetry separately, rather than as a whole. Gershom Scholem, for instance, was fascinated by the Safedian Kabbalists’ theosophical speculations, but he neglected their literary and legal output and the ways in which the three overlapped. This tendency toward compartmentalizing, Raz-Krakotzkin suggests, stems from adopting European frameworks that dismissed the value of the rabbinic tradition.[9] Similarly, he argues that ignoring Safed’s Ottoman context reflects Zionist historians’ desire to see themselves and Eretz Yisrael as part of Europe.

Though Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra is a stand-alone work, it can best be understood in the context of Raz-Krakotzkin’s seminal two-part essay “Galut Betokh Ribonut” (“Exile Within Sovereignty”). There, Raz-Krakotzkin argues that the notion of shelilat ha-galut (“the negation of exile”) stands at the heart of Zionist consciousness and practice. The Zionist interpretation of this phrase did not simply mean negating the physical galut. As Raz-Krakotzkin argues in Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra, Zionism sought to negate the multifaceted web of symbols with which galut was associated and to denude it of all connotations except the lack of political sovereignty. But, he argues, the broader symbolic structure of galut “is not just one foundation of Jewish existence―it is the central foundation of its definition.”[10] If galut is the essential component of Jewishness, then to “negate” galut is to negate Jewishness itself.

In reassessing the histories of galut and Zionism’s negation of it, Raz-Krakotzkin grounds himself in Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In one of the “theses” that Raz-Krakotzkin cites, Benjamin writes, “Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.”[11] In other words, history’s victors will enlist the past in service of their own narrative, in which their victory―no matter how brutal―was the inevitable and desirable outcome of historical progress. The very idea of “progress” itself is part of the problem for Benjamin. In one of the most oft-cited “theses,” he describes an “angel of history” flying backwards:

Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet… [A] storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.[12]

We see “a chain of events”: the “progress” that has brought us to our present state. The angel, by contrast, “sees one single catastrophe”: he sees all of the horrific death and destruction that such a state necessitated. As Raz-Krakotzkin explains, “The term ‘progress,’ with all of its meanings, and with all of the concrete uses to which it is put, reflects the consciousness of the rulers and nullifies the voices of the oppressed of the past.”[13] The task of the historian, accordingly, is to recall the past in such a way as to offer hope for alternative, redemptive futures and to highlight the contingency of the present. In doing so, the historian redeems the past, too.

For Raz-Krakotzkin, in negating galut, Zionism has embraced a “history of the victors.”[14] The Jewish past is seen as necessarily leading to the triumphant foundation of a Jewish state, without regard for the voices of those Jews who insisted on the meaningfulness of galut or Middle Eastern Jews who did not fit Zionism’s Eurocentrism, and Zionism’s success is seen as “progress” without regard for their marginalization in Israeli society. Understanding Zionism solely as a narrative of progress, Raz-Krakotzkin insists, also means “the denial of the Palestinian tragedy that accompanied the establishment of the State of Israel” and ignoring “the dispossession of Arabs from their lands… and the creation of the refugee problem.”[15]

In enlisting Jewish history solely in the service of the nation-state, Zionism strips that history of the critical possibilities it might offer for challenging the status quo. But recentering the notion of galut, Raz-Krakotzkin argues, would allow for alternative forms of Israeli-Jewish identity that in turn could offer new possibilities for peace between Israelis and Palestinians. An Israeli Jewishness that highlighted the exiled voices of Mizrahi Jews would no longer solely see itself as part of a European West in opposition to an orientalized East.[16] And an Israeli Jewishness that saw its own exile as bound up with the fate of the world and the cosmos’ exile would be forced to reckon with the Palestinian exile upon which Zionism’s success was predicated.[17]

Critically, Raz-Krakotzkin emphasizes that his goal in highlighting the galut is not to “return to the past, and certainly not an idealization of the historical reality of exile.”[18] But rather, his goal is to “to give back to the present that past whose denial is a part of that present.”[19] In concrete terms, this means using galut as a way of critiquing the present in the service of an egalitarian and binational future in Israel/Palestine.[20]

Benjamin appears only rarely in Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra, but the book must be seen as Raz-Krakotzkin’s attempt at fulfilling the task he set in “Galut Betokh Ribonut”: to resuscitate galut as part of, in Benjamin’s terms, “[t]he tradition of the oppressed.” Safed offers a way of relating to Jewish history, Eretz Yisrael, Mizrahi identity, exile, and redemption that eschews Zionism’s narrative of progress and challenges its turn to the West. In one of the few explicit references to Benjamin, Raz-Krakotzkin uses the “theses” to frame the difference between Zionist and Safedian relationships to history and practices of remembrance:

Zionist archeological reconstruction is designed to achieve control, conquest, and justification of the present… [it] is a practice of penetration, sometimes violent, that was not infrequently based upon the destruction of later [archeological] layers, i.e., Muslim ones. In Safed, by contrast, connecting to the historical moment of the Tannaim is not conducted by way of lord-like penetration of the land but rather by searching for the revelation that the spirit of their time continues to dwell in a place, by connecting to the exiled Shekhinah who sanctifies the land and is exiled within it. In the language of Walter Benjamin, the past appears “a breath of the air that pervaded earlier days [that] caress[es] us as well.”[21]

In Raz-Krakotzkin’s understanding, Zionism violently (metaphorically and literally) seized the biblical past in order to legitimate a present conquest. The Kabbalists of Safed, on the other hand, used mystical techniques to reconnect to a Mishnaic-Kabbalistic past that underscored the brokenness of the present. Such Benjamin-esque acts of recollection allowed them to experience the fullness of exile and thereby recommit to the work of cosmic redemption.

Are we meant, then, to simply return to Safed? Just as he makes clear in “Galut Betokh Ribonut” that he offers galut not as an alternative but instead as a standpoint from which to critique the present, in Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra, too, he states that his goal is “not [to present] a historical alternative but rather an alternative discourse,” one which recognizes “the possibilities that exist within the present.”[22] Citing Benjamin, he concludes that “we may return consciousness of the exiled Shekhinah into the reality of our lives, and thereby return galut consciousness to the discussion about political sovereignty.” Safed and galut are not intended as a replacement for Israel’s social structure but rather as cultural and political possibilities that may yet exist within it. What would an Israeli political-religious consciousness that recentered galut look like? How would it relate to the exiled voices of Palestinians and Mizrahi Jews? Perhaps galut is more important now than ever. This “one single catastrophe” might force all of us to reckon with the interwovenness of our exiles―Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Palestinian, and divine―and thereby reawaken the possibility of redemption.

[1] Mahmoud Darwish, Journal of an Ordinary Grief, trans. Ibrahim Muhawi (Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books, 2010), 26.

[2] Hayyim Yosef David Azulai, Marit Ha-Ayin (Livorno, 1805), 10b. All translations from Hebrew are my own.

[3] Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra: Tsfat Ve-HaTarbut Ha-Tzionit, (Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute Press/Hakibutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 2022), 104.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 68 n. 26, 142-144, 147.

[7] Ibid., 62.

[8] On the persistence of Cordoveran Kabbalah, see Moshe Idel, “Major Currents in Italian Kabbalah between 1560-1660,” Italia Judaica 2 (1986): 243-262; reprinted in David B. Ruderman, ed., Essential Papers on Jewish Culture in Renaissance and Baroque Italy (New York: New York University Press, 1992), 345-368.

[9] Raz-Krakotzkin, Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra, 21-22.

[10] Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, “Galut Betokh Ribonut: Le-Bikoret ‘Shelilat Ha-Galut’ Be-Tarbut Ha-Yisraelit,” Te’oriah Ve-Bikoret 4 (Fall 1993): 27.

[11] Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 2007), 255. Italics in the original.

[12] Ibid., 257-258.

[13] Raz-Krakotzkin, “Galut Betokh Ribonut,” 36.

[14] Ibid., 39.

[15] Ibid., 47. Though Raz-Krakotzkin lauds the developing conversation in Israeli society about Palestinian refugees that was taking place at the time in response to the work of the “New Historians,” he laments that critiques of their work focused on questions of responsibility and intentionality: “This does not allow for relating to the Palestinian tragedy as a central fact in the history of the land and Zionist settlement. The question of guilt is a question that guides ‘a history of the victors’” (ibid.).

[16] See Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, “Galut Betokh Ribonut: Le-Bikoret ‘Sh’lilat Ha-Galut’ Be-Tarbut Ha-Yisraelit II,” Te’oriah Ve-Bikoret 5 (Fall 1994): 128.

[17] Raz-Krakotzkin, “Galut Betokh Ribonut,” 49-51.

[18] Ibid., m. 26.

[19] Ibid, 49.

[20] For more on egalitarian binationalism, see Bashir Bashir, “The Strengths and Weaknesses of Integrative Solutions for the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Middle East Journal 70, no. 4 (Autumn 2016).

[21] Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, Toda’at Mishnah, Toda’at Mikra, 148-149. The translation of Benjamin is from Michael Löwy, Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History,” trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso Books, 2016), 29-30.

[22] Ibid., 218.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.