Ronnie Perelis

The first time I heard Leonard Cohen was from a scratchy cassette tape.[1] My dear friend and havruta offered to play me a song during a late Thursday night colloquium inspired by some duty-free Crown Royal. The song was “Suzanne” and I never heard anything like it- it was simple and direct and mesmerizing. I loved its mysticism and imagery. I was moved by the song’s sensuality and yearning after God.

It was a few years later when I found him again. At a Shabbat meal at another friend’s house I saw a copy of Cohen’s Book of Mercy. Again I was reminded of his music but I saw something else there; in this little book – my friend’s edition had the signature heart-magen david insignia that Cohen himself crafted- I sensed that these sorts of words were not written down by a contemporary. The lines felt like ancient Hebrew, like Biblical images and ideas transposed into modern English. It was also striking that here was a contemporary book that read like a collection of jagged, earthly prayers.

In the years since, I and many others have re-encountered several new iterations of Cohen’s art, spirituality, and music. When after many years of semi-seclusion Cohen went out on tour in 2009 at age 74, releasing new albums that mined the depth of his experience, he shared the shards of broken light with new audiences around the world. By the time of his passing in the fall of 2016 Leonard Cohen left behind a varied and unique body of work, as well as his own low key self-mythology that left fans yearning for more of the man and his art. The exhibition, Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything, that debuted at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC) and is now at the Jewish Museum in New York, can provide devoted fans and newcomers access to a sort of Leonard Cohen afterlife. The exhibition is premised on Leonard Cohen’s multitudinal and capacious life and work. It approaches its subject not like a biographer or a critic. Rather, it is interested in the reverberations of his music and the interplay of artists and art and audience.

Even the most documentary-like space at the exhibit—the 56 minute video installation Passing Through created by George Fok—is not a passive viewing experience. Using multiple screens arranged around a rectangular space the film traces Cohen’s career, both his art and his life, as a sort of time machine. It begins with the performance of one of his early songs, sometimes cutting back into the background of the period in which it was written using some gems of archival material from around the world—and then side by side with the earlier performance of the song we see a screen of Leonard singing the same song decades later—sometimes there are three performances running simultaneously—from the sixties, late eighties, and his final years of touring in 2000’s—all side by side. At one point he intones, “I dedicate this song to a talented American singer”, and then goes on to tell a by-now famous story[2] of his encounter with Janis Joplin at the Chelsea Hotel. The screens light up with Cohen telling the same story, the same punch lines but through several decades—it’s the same and it is transformed as he ages, and the audiences change, and the world changes.

In another space, “Heard there was a Secret Chord” dedicated to Cohen’s most overdone song, “Halleluyah,” we see a dimly lit space with microphones hanging from the ceiling, snaking around an odd octagonal bench of white wood. Up in a corner is a small digital sign with numbers that keep on changing. The sound piped into the room is a hummed, acapella version of that broken, pathos-drenched anthem; the volume of the song increases or decreases depending on the amount of people worldwide at that moment who are listening to the song—the digital sign is keeping track of those global listeners. The microphones invite you to hum along. And hum people did. The day I was there most of the mikes were taken by people of different ages humming along to the tune, adding their voice to this global choral of heartbreak and longing.

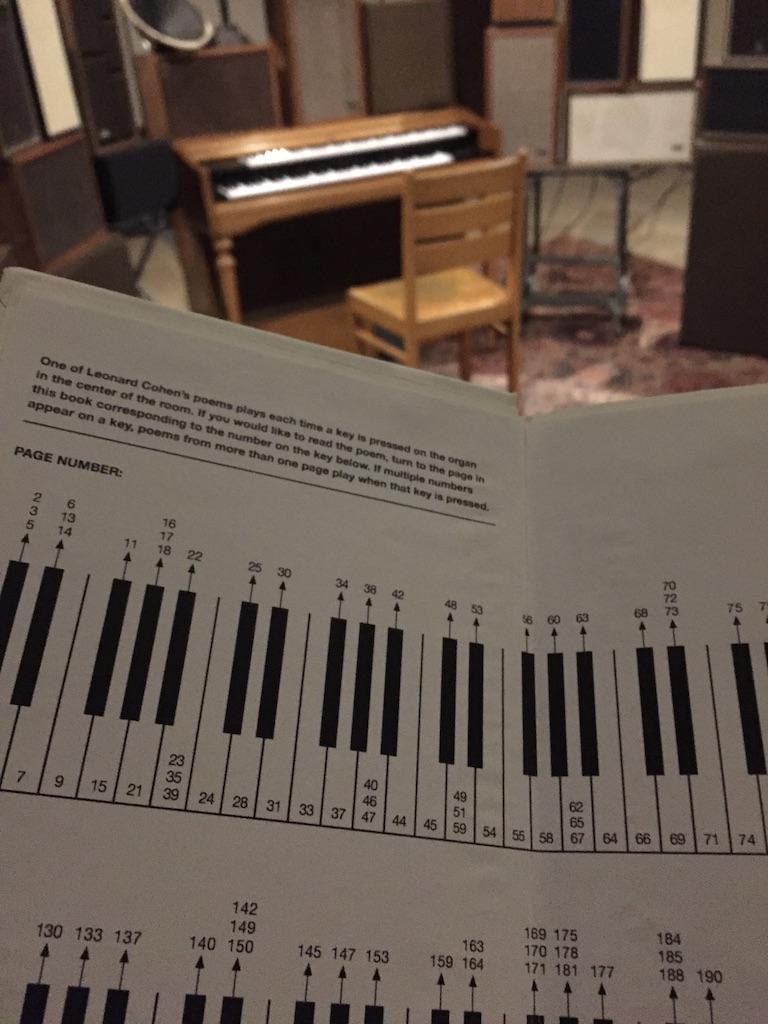

In another room we encounter “The Poetry Machine”. In this installation, conceived of by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, we find a 1950’s Wurlitzer organ with an array of vintage speakers carefully set up around it, with a simple and elegant oriental rug to set the stage. The rug is reminiscent of the stage set of Cohen’s last years of touring, with his exquisite band, all dressed in black suits and fedoras and the floor of the stage draped in lush rugs upon which Leonard, at once a monk and an entertainer, would kneel, and bow in the heat of a song. The wood of the speakers reminded me of the simple, elegant, and warm décor of his sparse Montreal apartment where he did so much of his writing throughout the years. You are invited to sit down at the keyboard and play. Each key sets off a recording of Cohen reading a poem from his Book of Longing. You can play several poems at once, creating a strange song of words and pauses, rising and falling, jamming into each other and resolving at times in harmony. Or just let a poem go to the end. It was awfully fun and disorienting to be in the room, either listening or “playing”. When I left I felt my hands buzzing, like I was tapping into some portal. I wanted to return and spend more time there, playing around with the endless variations of words and pauses, of the undulations and raspiness of his voice and the anger, humor, and beauty of these earthy poems.

On the third floor of the exhibition we walk into a darkened room and before us is a large rectangular screen featuring the members of the Shaar HaShomayim Synagogue Choir. This choir sings regularly at the synagogue that Leonard Cohen’s family helped found in the upscale Westmount suburb of Montreal. These singers along with the synagogue’s cantor, Gideon Zelermyer, sang backup on Cohen’s last album, most famously on his channeling of the Kaddish, the haunting and very personal “You want it darker”. Here, however, they are singing back up to the songs from what is considered by most of Cohen’s biographers as his first comeback album, I’m your man from 1988, as part of Candice Breitz’ installation by that same title. To the right and left of the screen are two arrows pointing toward the second part of the installation, a long room lined with 18 screens, each featuring a different middle-aged or elderly Leonard Cohen fan singing the entire album, song after song. One gentleman decided to evoke the master by wearing a fedora, a grey dress shirt and tie and black suit jacket, another is wearing a Cohen concert t-shirt, one older bearded man is wearing a dress. Most did not seem to get dressed up in any particular way for the occasion. As you walk around and hear their 18 man version of the album, backed up with the acapella humming of the chorus, you can hear how each person makes each song their own.

I felt drawn in, as if the singers were reaching beyond the screen with their eyes and hands, their swaying and reverie. They were inhabiting the song, and wanted to share it. I looped through the room twice and then went back to the first room with the chorus, the singers were keeping time with the song playing in the main room, waiting for the right moment to enter and offer the deep amber of their harmony to the uneven collection of 18 men pleading with their lovers, assuring them that they are “your man” or reminding their unknown audience about what “everybody knows.”

The exhibition wants you to engage with Leonard Cohen, not necessarily to “learn about him” or appreciate his work. It celebrates the way his art has inspired others to create and to live more deeply. And it is here that I think Leonard Cohen’s life work, and this exhibition, is useful for Modern Orthodox Jews. It is not the Judaism that finds its way into his art or is refracted in any of these artistic engagements at the exhibition that is relevant here. I believe that there are certain sensibilities inherent in Cohen’s art and in his spiritual journey that can help Jews trying to live deeply with Torah while engaged in the world at large. I believe that the exhibit gives us access to some of those ways of being, in particular his humor, his vulnerability, and his co-mingling of the earthly and the transcendent.

The exhibit spends surprisingly little time and space on Cohen’s religiosity. You see scenes from his childhood synagogue, you see Cohen in Israel during the Yom Kippur war, and a stirring, trancelike rendition he gives of a Yiddish song—“Un As Der Rebbe Singt” (“As the Rebbe Sings”). There are also poignant references to the Shoah and its lingering shadow on much of his life and work. It is clear that he owns his Jewishness and carries it with dignity. It is rather stirring to see his easy pride and the way he was able to be so rooted in his particulars- his Judaism, his Montreal roots, and at the same time be such a man of the world. But there is no installation that engages Cohen’s deep, wide ranging, and creative engagement with Judaism or other religions, such as his years as a Zen monk at the monastery on Mount Baldy, California.[3] Perhaps this points to the difficulty and unease of the art establishment with religion.

This lacuna surprised me but did not diminish my enjoyment of this often revelatory exhibition. I was reminded of so many of the gifts that Cohen brings his listeners. I was struck again and again throughout by his humor. He had impeccable timing, leading his audience into the story and then trapping them in the joke. He was decorous and suave but could make fun of that pose at the same time. We can see this in pitch-perfect display in a scene from his performance of “Tower of Song.” It comes from a recording of a live performance in London in 2008. “Tower of Song” is about death and memory and art and loneliness, but here he plays it with such easy, bizarre humor. Around five minutes into the song Cohen stops singing, allowing the back-up singers, the Webb Sisters and his longtime collaborator Sharon Robinson, to sing the “doo-dah-dum, doo-dah-dum.” They sing this sweetly and their voices are hypnotic. After a few rounds of their singing he addresses the audience and tells them that: “Tonight the great mysteries have been unravelled. And tonight I’ve penetrated to the core of things. and I have stumbled on the answer.” He assures his audience that he has the answer to the mysteries of the universe and that he is ready to reveal that secret. And then he listens ever more closely to their singing; the rhythm which has not stopped throughout his monologue, and with a mischievous smile, he points to the singers- “doo-dah-dum, doo-dah-dum”— that’s the secret he has come to reveal!

For a moment, when watching the performance, perhaps we may think (or want to think) that he will reveal that secret but Cohen makes sure to kill the Buddha and any easy answers he may offer. Cohen, of course, spent his entire life seeking these answers and it is precisely for this reason that his listeners will listen to what he has to say; this is precisely why he wants to disabuse them of any easy answers to life’s big questions. He also has so much fun and invites his listeners in on the joke and the joy, but also makes the harder edge of the song easier to absorb. Humor is disarming, it opens us up. Perhaps that is why Rabbah the Talmudic sage would always begin his teaching with a joke (Shabbat 30b). The hasidic masters explain that humor can take us out of our place of psychological constraints—from the mohin d-katnut (the small mindedness) to an expansive consciousness of mohin d- gadlut. We need to remember to laugh, especially at ourselves and the things we cherish. Laughter is an antidote against fundamentalism. Der mentch tracht und Got lacht—Man tries (or plans) and God laughs.[4] Our plans, our great intellectual and ideological constructs, are all variations on a theme as we stumble towards the light. Living a life of faith does not give us the answers, it inspires us to search and grow and to give. If we approach that path without humor and humility we set ourselves up for disappointment or worse.

Cohen also sets out on a path of spiritual striving and searching which embraces the brokenness of that very search. Shlomo Carlebach would often say that God is closest to the broken-hearted (Psalms 34:19) because they are most capable of letting Him in. This idea, rooted in the words of the Psalm and in the hard-won wisdom of the religious life is wrapped up in Cohen’s aptly titled “Anthem”:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

Perfection, especially in matters of the spirit, can trap us. By accepting our flaws and nonetheless never giving up on the struggle towards the light we insure that we are continually engaged with the divine, that God is at the center of our lives. Embracing our vulnerability opens us up to empathy for others and a deeper hunger for the Transcendent.

The ideals of Torah u-Maddah call on the Modern Orthodox Jew to live a dialectical life. Walt Whitman reminds us that we “contain multitudes” and we are enjoined to use these varied gifts to enhance and deepen our Avodat Hashem. But it is hard to know how to balance often opposing drives and values. Living with this tension is at the heart of a modern religious life and again Cohen’s sensibility may be of use here. Cohen is a master of juxtapositions. A trademark of his art from its earliest moments is the play between the spiritual and the carnal, between darkness and light, the transcendent and the everyday. Being able to live with multiple, opposing ideas and feelings and commitments is an essential feature of modern life, but specifically of Modern Orthodox life. If we as individuals and a community are to transcend a bifurcated life—where our modernity and our orthodoxy operate in separate spheres, or where modernity is only seen as a utilitarian tool, aiding our spirituality in technical or financial ways, we must learn to live with ambiguity and contradictions and create something beautiful, luminous, and holy out of the confusion and brokenness.

Cohen’s sensuality is always tinged with the spiritual, the existential, and often enough with deep pain. Cohen says that one of his great love songs, “Dance me to the End of Love,” began as a meditation on the origins of evil; he wrote it while visiting Berlin and the Shoah was on his mind. It turned in a different direction but his grappling with horror found its way in:

Dance me to your beauty with a burning violin

Dance me through the panic till I’m gathered safely in

Lift me like an olive branch and be my homeward dove

Dance me to the end of love

Dance me to the end of love

He calls to his lover, seeks out her beauty but also her comfort. On the surface the burning violin evokes passion; but in an interview, Cohen says that the image was inspired by the prisoners in the death camps who were ordered to play music “while the Nazis did their killing work.” Love, lust, chaos, cruelty, and hope all wrapped together in a dance. Cohen’s ease with the full range of human experience and its messiness is another portal for us to enter through. From the Bible to Hazal to the great medieval poets and mystics, our tradition embraces the fullness of the human experience. However, the shock of modernity with its radical assault on religion along with the dislocations of the 20th century have pushed much of our orthodox culture to react by containing these opposing spheres, of normalizing and categorizing our passions instead of celebrating and channeling them. Rav Kook z’l looked forward to when the Jewish body—degraded through 2 millennia of exile from its full physicality—will join with the Jewish soul.[5] Perhaps an embodied spirituality is easier in the Land of Israel. Jewish soldiers, and farmers, and engineers and doctors, Jewish poets crafting songs out of the layers of Hebrew, hewn out of the lived experience, can create art that is deeply spiritual and sensual, transcendent and quotidian. Evayatar Banai’s “Yafa keLevana/Beautiful like the Moon” is a striking example of a pious musician taking the fullness of his life into his music and creating songs of tenderness and passion. In Israel there is a blossoming of music and art and film that is going in this direction from Etti Ankari’s interpretations of the poems of Yehuda Ha-Levi or the Breslov-inspired songs of Shuli Rand and so many more. But in English I can’t think of a better place to start this project of spiritual-sensual revitalization than Leonard Cohen’s work.

In 2011 Cohen received Spain’s[6] highest honor, the Premios Principe de Asturias. A small clip of Cohen’s acceptance speech played towards the end of the video installation Passing Through. We see a wizened, elegant man address the Spanish Royal Family with humility and grace but also with a piercing insight into the power of art:

Now, you know of my deep association and confraternity with the poet Federico García Lorca. I could say that when I was a young man, an adolescent, and I hungered for a voice, I studied the English poets and I knew their work well, and I copied their styles, but I could not find a voice. It was only when I read, even in translation, the works of Lorca that I understood that there was a voice. It is not that I copied his voice; I would not dare. But he gave me permission to find a voice, to locate a voice, that is to locate a self, a self that is not fixed, a self that struggles for its own existence. As I grew older, I understood that instructions came with this voice. What were these instructions? The instructions were never to lament casually. And if one is to express the great inevitable defeat that awaits us all, it must be done within the strict confines of dignity and beauty.

Cohen does not sound like Lorca, but Lorca’s voice could be a model for his own. In a similar way I would never call on our intimate community to sound like Leonard Cohen or to live their lives along the lines of his own. However, I believe that his art and life can offer us new ways to live our Torah lives, or perhaps it can serve as a reminder of the things we already know but need help accessing or articulating.

[1] The Lehrhaus has already featured well-written and insightful pieces on Cohen’s work. These saw his poetry as Torah, or at least as engaged with Torah. This is right and good and I look forward to seeing more such engagements with his work. After all, he saw his poetry as inspired by and functioning as liturgy and of course it is Leonard Cohen himself who confessed to being “the little Jew who wrote the Bible.” I come to this material as a reverent, love-struck listener and reader of Leonard Cohen’s music and poetry. I am a fan; I will admit it. But I wanted to write a review, specifically for the Lehrhaus, because I wanted to think about what Cohen can mean for Modern Orthodox Jews.

[2] This piece from Rolling Stone offers some useful background to Cohen’s encounter with Janis Joplin at the Chelsea Hotel.

[3] When Cohen embarked on his major comeback tour in the 2000’s the New York Times published a small article and included an audio recording of Cohen describing a Hanukkah encounter he had while living in the monastery. One cold night he met some young Habad Hasidim who were lost, he invited them into his spare cabin, took out a bottle of Crown Royal and they lit Hanukkah candles. Cohen never let go of Judaism even as he lived the life of a Zen monk. The audio recording where Cohen retells this story does not appear on the story’s current digital version. But these line might be useful:

Mr. Cohen is an observant Jew who keeps the Sabbath even while on tour and performed for Israeli troops during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. So how does he square that faith with his continued practice of Zen?

“Allen Ginsberg asked me the same question many years ago,” he said. “Well, for one thing, in the tradition of Zen that I’ve practiced, there is no prayerful worship and there is no affirmation of a deity. So theologically there is no challenge to any Jewish belief.”

Zen has also helped him to learn to “stop whining,” Mr. Cohen said, and to worry less about the choices he has made. “All these things have their own destiny; one has one’s own destiny. The older I get, the surer I am that I’m not running the show.” Larry Rohter, “On the Road for Reasons Practical and Spiritual”

In an early interview included in the exhibition, Cohen mentions that he sometimes would like to be invisible. The interviewer asks if he would like to change his name—he said- yes, I thought of changing my name to September.

Leonard September? – no September Cohen.

The interviewer seems to assume that he would like to lose his deeply Jewish name, but that was not ever a question for Leonard Cohen.

[4] On this point see Milan Kundera’s meditation on the novel as a recording of God’s laughter in his acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize published in his collection of essays, The Art of the Novel.

[5] Orot, “Orot ha-Tehiyah“, ch. 33, 80.

[6] For much of his career, Cohen was more popular in Europe than he was in North America. This may explain why Spain would give its highest cultural prize to Cohen. His speech explains the deep debt he felt toward Spain, down to the very guitar he used to write his greatest songs. Cohen named his daughter Lorca, an homage to his muse and phantom mentor.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.