Editors’ Note: The Orthodox Union’s recent statement regarding professional roles for women in Orthodox synagogues has sparked heated debate for the sake of heaven. In the hopes of contributing to that ongoing conversation, Lehrhaus has convened a symposium to reflect upon the statement. Over the course of the next week we will post further installments, so please check back frequently. Each contribution will contain links to the other pieces in the symposium.

Symposium Contributions: Sara Wolkenfeld, Tzvi Sinensky, Shmuel Winiarz, Leah Sarna, Rivka Press Schwartz, Matt Reingold, Laura Shaw Frank, Chaim Twerski, Chaim Trachtman, Shayna Goldberg, Shaul Robinson, Todd Berman, Jeffrey Fox, Elli Fischer, Jeffrey Woolf, Zev Eleff & Ari Lamm

Elli Fischer

The recent OU paper on women as clergy in the Orthodox community, as well as the numerous responses it has generated, here at Lehrhaus and elsewhere, has produced an extraordinary, high-resolution snapshot of the state of American Orthodoxy. It has been quite valuable in that regard. However, focus on the fine detail of the present has obscured the place of this document in the longer historical arc. I therefore want to look at the document through three historical lenses; it’s an attempt to situate it within a broader narrative.

I. What Schism Looks Like

The first lens through which to evaluate the OU paper is the lens of “schism.” Several of the initial reactions to it have declared that it creates an unbridgeable rift between the segment of Orthodox Judaism it addresses and the segment of Orthodoxy that favors the ordination of women.

Perhaps it is to the credit of our community that this document could be mistaken for being schismatic; though schism is no stranger to Judaism, it has been several generations since there has been a broad-based movement to seal one segment of Judaism off from another. There have been attempts—Prof. David Berger’s call to dissociate from Chabad messianists is one recent example, and there certainly are some people today, on either side of the divide, who are calling for schism (in fact, Prof. Berger has written about it)—but they have not succeeded.

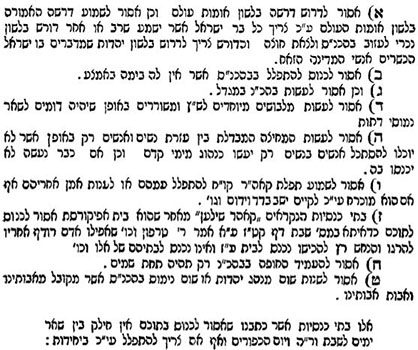

What does schism look like? Let us consider one particularly salient example: the psak din (verdict) of Michalovce from 1865 (the image appearing at the top of this essay pronounces the verdict; for an English translation of the document in its entirety, see here). This document was signed by close to a hundred rabbis from “Unterland,” that is, the religiously conservative northeastern reaches of pre-World War I Hungary. It did not present itself as a policy paper or as a legal opinion, and it did not use soft language like “we believe.” Instead, it puts forward unequivocal pronouncements; it is presented as a “verdict.” Its target was not only non-Orthodox movements, but also, and perhaps primarily, modernizing forms of Orthodoxy, as championed by Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer and others.

Moreover, it does not merely forbid certain practices—preaching in the vernacular, placing the bimah anywhere but the center of the synagogue, erecting a mehitzah that does not make it impossible for the men to look at the women, etc.—but forbids entering a synagogue where these are practiced, even if it means that one will pray alone on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

The Michalovce verdict might be an extreme example, but even in comparison with other unquestionably schismatic documents—Eleh Divrei Ha-Berit (“These are the Words of the Covenant”), which responded to the opening of the Hamburg Temple in 1818-1819; Rabbi Elazar Fleckeles’s persecution of the Prague Frankists in the first years of the nineteenth century; and the various bans pronounced in Vilna, Shklov, and Brody in response to the nascent Hasidic movement—it is clear that the authors of the OU document were trying very hard not to cause schism. Nowhere does it forbid adherents to step foot in a synagogue that employs a clergywoman. Nowhere does it threaten such congregations with expulsion from the OU. Nowhere does it intimate that it is better to pray alone on Rosh Hashanah even when the only available shofar is in that synagogue.

Several responses to the OU document have noted that it seems to be internally inconsistent, that its prohibition of clergywomen offers so many counterpoints and carves out so many exceptions that it would be all but impossible to apply it to any woman based on her role in the synagogue. While this insight into the document is correct, it seems to me that this obfuscation is not a bug, but a feature. The purpose of the document is to articulate a position without drawing a bright line between those who are “in” and those who are “out.”

II. Orthodoxy and Change

Here’s another lens: religious change. Had the OU document been released in 1977 instead of 2017, it would have espoused a position that was more liberal than that of the Conservative Movement. When the Conservative movement finally did permit the ordination of women in the early 1980s, part of its traditionalist wing broke away to form a new movement, called UTCJ (the Union for Traditional Conservative Judaism; in time, the group dropped the “C”). Around the same time, Rabbi Hershel Schachter and several other roshei yeshiva from Yeshiva University authored a short responsum that forbade women’s prayer groups.

Several prominent members of UTJ now support the ordination of women, and in at least one case, the daughter of a rabbi who left the Conservative Movement over the ordination of women is herself studying for ordination, with her father’s blessing. As late as 1998, Rabbi Avi Weiss, who founded the first institution for granting ordination to Orthodox women, Yeshivat Maharat, was on record opposing the ordination of women on halakhic grounds. (Perhaps ironically, there was a short-lived attempt in the early 1990s to unite UTJ and the liberal wing of the Orthodox rabbinate (including Rabbi Avi Weiss) in a single organization, called FTOR, the Fellowship of Traditional Orthodox Rabbis.) I recall a conversation with one of the OU paper’s signatories around the same time, in which he said, “Our daughters will study Gemara and no one will bat an eyelash.”

It is clear, then, that it takes time for certain insights to percolate into halakhic discourse; Orthodoxy is inherently, constitutionally, resistant to and suspicious of change, as is any conservative social grouping. In some cases, excessive agitation for change on the part of some will be met with an equal and opposite reaction, born of a sense that our predecessors—whether the great Torah scholars of previous generations, or our own grandfathers and grandmothers—did not, God forbid, adhere to immoral or unethical codes of conduct. Change runs the risk of being motzi la’az al ha-rishonim, of undermining and casting aspersions on the very foundations of our self-perception and sense of continuity, the very foundations of commitment to a life of Torah and mitzvot.

III. Rabbi: Credential or Job Description?

The third lens through which to view the OU paper is the shifting meaning of the term “rabbi,” and in two different ways. The first shift is from job description to credential. Once upon a time, ordination was conferred when a Torah scholar was seeking it, or it was offered. Rarely was there more than one rabbi (or mara de-atra, or av beit din) per city or district. Torah scholars who were further down the hierarchy, even if they were great Torah scholars, were known by lesser titles: moreh tzedek, melamed, shohet u-bodek, dayan, resh metivta. Learned laypeople were given the title morenu or, if a truly worthy Torah scholar, haver.

Today, especially in the United States, the term “rabbi” has become a catch-all title for every male religious functionary. Every shohet, every mohel, every third-grade rebbe is known as “rabbi,” often even if they have not been ordained. At the same time, it has become easier and easier for men to be ordained. There are numerous online semikhah programs; there are “kiruv professional” training courses that grant semikhah to men who pass an open-book test on fifty pages of Talmud of their choice and the concise code of Jewish law, Kitzur Shulhan Arukh, by Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried (incidentally, one of the signatories of the Michalovce psak din). Thus, more and more men with less and less Torah scholarship are called “rabbi.” The title has gone from job description to credential, and a very watered-down credential at that.

While the term “rabbi” remains charged by its history, the fact that the Orthodox community, by and large, has not found a way to recognize the credentials of female Torah scholars is unjust. Not only does it deny these women the respect they deserve, but the lack of recognized credentials often results in lower salary (in addition to the ever-present wage gap) and exclusion from communal leadership positions that are not really “rabbinic” (Hillel directors, rabbis-in-residence for organizations, school principals, and other positions that seek candidates who have rabbinic ordination or advanced degrees in Jewish studies). Not only that, but the Orthodox community ends up shooting itself in the foot, as these positions are often filled by non-Orthodox rabbis, even as Orthodox women are equally qualified, if not more so.

The OU paper addresses the question of whether women can be appointed to “rabbi” jobs, an important question of halakhah, self-perception, and communal policy, in a manner that strains to prevent schism even while staking out a position. It does not address the question of recognizing credentials—whether by means of the catch-all title “rabbi” or by other means. This is a question of basic fairness and respect for Torah scholarship. This remains our challenge.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.