Ayelet Wenger

Shabbat lunch, Jerusalem. Everybody around the table is a retired senior citizen, a counter of grandchildren, an immigrant to Israel playing out the Zionist dream in a securely Anglo environment.

“This is Rachel. Rachel just moved to Jerusalem from Toronto.”

Everybody nods and passes the salad. The Zionist dream on repeat.

Now the hostess reveals her card.

“Rachel survived the Exodus.”

Everybody looks up. Paul Newman’s smile.

“I survived the Holocaust,” Rachel quietly corrects.

Everybody does not know what to say.

There once was a ship called Exodus:

Some stories run in the family. My family gathered around the television every Tisha Ba’av afternoon for the annual viewing of Exodus, the shudder when Dov Landau vows to join the Irgun, the thrill when the flag goes up and the food goes overboard, the maternal mutterings that one should not marry a goy, even a nice American one.

There once was a ship called Exodus:

Someone asks Rachel what it was like. How she found out about this ship, this Exodus. How the ship passengers slept on shelves just like in the concentration camps. How the hunger strike meant refusing British food, not throwing food overboard. How the ship did not bring Rachel to Israel. It brought her to Germany.

The Hebrew University, Jerusalem. Everybody is waiting for the professor to show up. Behind me, an aged man not wearing a kippah catches the man with curly sidelocks and he wants to know.

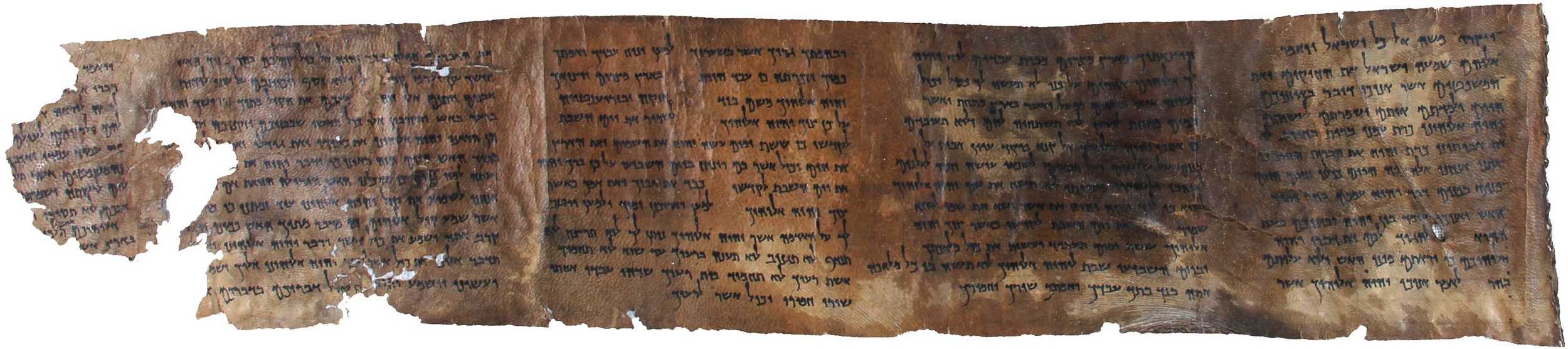

“Did God write this?” The man without a kippah waves a book at the man with curly sidelocks. It is a familiar book. I am holding it too. Mine was given to me not on a mountain but in a high school lobby in Manhattan. The pages are seeped with things I’ve found and loved and resented and wondered about, invisible exclamation points that never got on the page because only God can write in this book.

“Did God write this?” insists the man without the kippah.

“I don’t know,” says the man with the curly sidelocks. “I don’t think you know. I don’t think anybody knows.”

“I know,” says my mother.

A thousand scholars clamor against her confidence, crashing extensive footnotes into the slippery slopes of a mountain that will not move. Against this faith that moves mountains there are no questioners to ask what happens if our blindfolds and knitting needles and Band-Aids teeter like hilltops upon a thread of hair, if the many voices of Rav Mordechai Breuer’s Deity break into schizophrenic cacophony, if things fall apart.

“How do you know?”

“I know. Trust me. I was there.”

“There was never another prophet like Moses.”

“How could Moses say this?” chortles the professor. “Whoever said this clearly lived long after Moses, since he knows about the prophets who lived after Moses died. Moses could not know about prophets after him.”

In the dusty shelf life of my classroom daydreams, a braver Ayelet raises her hand and says that she once read in some Divine language, somewhere, something, someone who believed Moses could know what came next, Moses could prophesy, Moses could prophesy so well that there was never another prophet like Moses.

The professor would peer down at this last vestigial structure of witch-hunts and amulets, explain that she must have read such antiquated nonsense in The Little Midrash Says, and dismiss the class. The disciples file out, trampling over eraser stubs and fragments of shrieking word.

ת              J              θ              E              ל              ε              P              י              ο              D              י              ς              א

If we had evidence, he says. If one of those four documents poked its nose out of the sands of Egypt or Palestine like a lone son at the Seder table, looking around and asking what all this is for. His Rebbe taught him to lift hands to Heaven, to shriek My God why are you testing me. He shakes his head. If we had that kind of evidence, he says, what’s the point. If we had that kind of evidence, let’s all go home.

But I have no other home.

The Nazis are boarding the train, checking for Jews. Rachel and her family look at each other. Someone whispers a prayer. Someone answers with a prayer. They start chatting in prayer, repeating the strange words that they were taught to whisper at bedtime. The Nazis reach them. The Nazis do not know the difference between the language of the locals and the language of the Divine. They pass over the Jews.

There once was a ship called Exodus:

There once was a professor who could pronounce the forbidden name with all the confidence of Albus Dumbledore. We are in his office reading an inscription and it is my turn to read and there on the page are His four letters and they must be read and he is waiting, and He is waiting.

“Ayelet?”

The Y Name. Ya…you know. I have never said The Name. One must not say The Name. But he says The Name. As it is written in the text. As it really is.

“Hashem.”

We are silent. There was something too forceful in my utterance, some shrill apologetic that hangs around and sticks to his bookshelves with the gloopiness of an unwashed Chulent pot.

Ay[el]et?

I went back to my Rav. He diplomatically suggested that, according to some opinions, one should not learn such things if one finds them troubling.

I could not explain to him why this hurts me. I could not explain that I have finally found a world of great Torah scholars who will teach me like they teach their men. I could not explain that I am tired of the second-rate education that he can offer me. I am tired of studying Gemara in the high school hallway and I am tired of mourning my exclusion from the good Yeshivas and I am tired of contemplating closed doors.

I could not tell him that I saw the best minds of my generation asphyxiated. I saw them wandering through schools and seminaries that don’t quite educate them, pasting together strings of postgraduate programs that don’t quite challenge them, grasping for positions that do not exist in communities that do not want them. Sometimes, as I watch my friends and heroines lacerating themselves against glass ceilings made of concrete, I thank God for making me an academic.

There was more that I could not explain to my Rav. I could not explain what I have found in this other world, this world that cares what I think, that thinks I can think. I could not explain that these grammars and theories and texts and manuscripts can tell me things about my sacred texts that Rashi never did.

I could not explain that I need to believe Torah can handle this. I need Rav Soloveitchik to be right when he says, “if the Torah cannot go out into your world of scholarship and return stronger, then we are all fools and charlatans. I have faith in the Torah. I am not afraid of truth.”

I could not explain this because it is a lie. The Rav never said these words. Chaim Potok said them. I wonder if it matters who said these words.

“If you publish this,” my friend says. “People will read it as your coming-out story. They will say, she does not believe in the Exodus.”

Something bites my tongue. That is not what I meant. That is not what I meant at all. I meant that Torah is a wriggling, wrestling, living tree, a tree that shatters into seventy faces and regrows into six hundred and thirteen, a tree of secret crevices and hollows and roots too deep for any human to penetrate. I meant that nobody lives “do you believe” as a one-word answer. There never was a yes. There was only yes and yes and yes and yes and yes and yes and yes and yes but, but, but yes

There once was a ship called Exodus:

“I always thought it was a true story,” says someone sadly.

Everybody around the table jumps to reassure everybody around the table that there really was a ship named Exodus after all, that the historical details aren’t the point after all, that the ship’s story is really only a small part of Leon’s book after all, after all, after all, after all it’s time for some words about this week’s Parsha. My step-grandfather clears his throat and begins an old, true tale, a tale written with the fingers of the Divine, stained and salted with the tears of Moses, a tale that no archaeologist, no mishnah in Sotah, no scholar can ever take away from me.

There once was a book called Exodus:

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.