Review of Don Seeman, Daniel Reiser, and Ariel Evan Mayse, Hasidim, Suffering and Renewal: The Prewar and Holocaust Legacy of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira (SUNY Press, Albany 2021).

Those who have studied his seforim may have some inkling of how their souls are elevated through the tzaddik [Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira], but it is impossible to adequately describe who he was and the profound relevance of his teachings to our generation in particular…

– R. Moshe Weinberger[1]

R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik once wrote that the religious experience of faith is “fraught with inner conflicts and incongruities” and “oscillates between ecstasy in God’s companionship and despair when he feels abandoned by God.”[2] Recent scholarly debates both on the internet and on the printed page[3] suggest that such an experience of faith may be the perfect description of that of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczno.

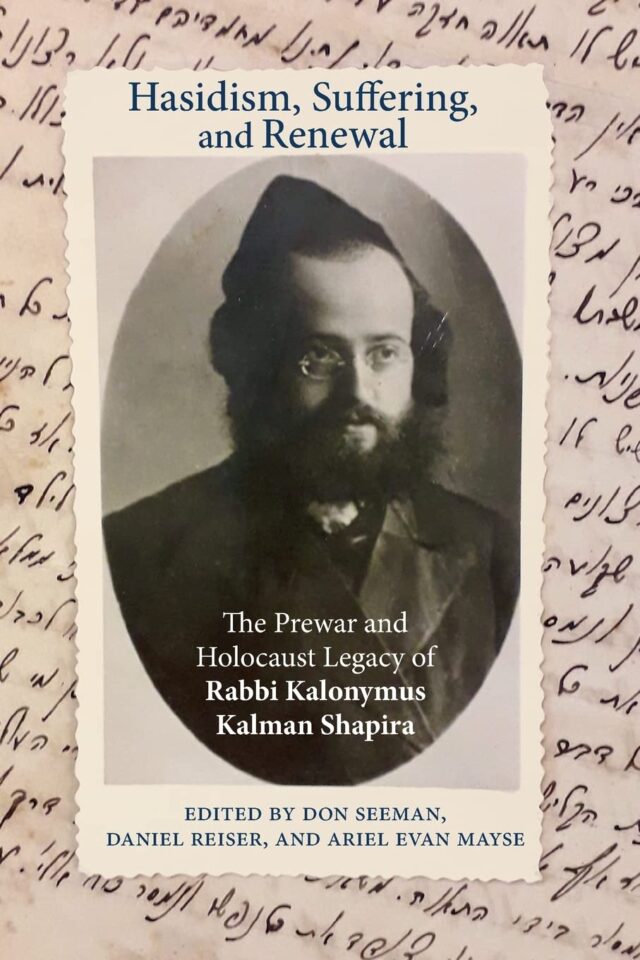

R. Shapira, best known for the sermons he delivered in the Warsaw Ghetto, is one of the most widely-read religious figures of our time. His works “have engendered a dedicated readership across a wide range of communities, from ultra-Orthodox to New Age and Neo-Hasidic, and have contributed to a public renaissance in appreciation for Hasidic ideas and texts”[4] across the globe. He is also the subject of Hasidism, Suffering and Renewal: The Prewar and Holocaust Legacy of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, edited by Don Seeman, Daniel Reiser, and Ariel Evan Mayse. This volume, the first collective scholarly analysis of R. Shapira’s writings and legacy, assembles a cross-disciplinary lineup of scholars in order to highlight new understandings of R. Shapira’s religious contributions and demonstrate the lasting relevance of his work from a variety of vantage points.

In addition to presenting a historical context for R. Shapira’s operation and various perspectives on his earlier, less studied writings, Hasidism, Suffering, and Renewal also highlights an intense debate about the nature of his faith by the end of his life which will be the focus of this review. The debate largely centers around a haunting footnote located in R. Shapira’s sermon for Shabbat Hanukkah 1941. However, the note itself has been dated to 1943 in Reiser’s critical edition of Derashot Mi-Shnot Ha-Za’am (popularly known as Sefer Aish Kodesh)[5], making it one of the last things R. Shapira wrote before the manuscript was hidden away. It reads as follows;

הג“ה: רק כהצרות שהיו עד שלהי דשנת תש“ב היו כבר, אבל כהצרות משונות, ומיתות משונות, ומיתות רעות ומשונות, שחדשו הרשעים הרוצחים המשונים עלינו בית ישראל, משלהי תש“ב, לפי ידיעתי בדברי חז“ל ובדברי הימים אשר ישראל בכלל, לא הי‘ כמותם, וד‘ ירחם עלינו ויצילנו מידם כהרף עין[6]

[Note:] Only such torment as was endured until the middle of 1942 has ever transpired previously in history. The bizarre tortures and the freakish, brutal murders that have been invented for us by the depraved, perverted murderers, solely for the suffering of Israel, since the middle of 1942, are, according to my knowledge of the words of our sages of blessed memory, and of the chronicles of the Jewish people in general, unprecedented and unparalleled. May God have mercy upon us, and save us from their hands, in the blink of an eye.[7]

This note, with its admission that the evils of the Holocaust were truly unprecedented in history and therefore apparently outside of the Jewish role in history as previously understood, has been the source of much discontent amongst scholars and theologians alike. Does it represent the strength, fracture, or collapse of R. Shapira’s faith in the face of an evil the likes of which had never been seen before?

This question is the subject of a passionate debate between Henry Abramson of Lander College and Shaul Magid of Dartmouth College in this volume. Abramson’s essay, “‘Living with the Times’: Historical Context in the Wartime Writings of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira”, acknowledges that the footnote signifies R. Shapira’s realization that “a fundamental change had occurred in the universe”[8] and that this recognition had a traumatic impact on his internal spiritual outlook. However, Abramson sees the question of whether or not Shapira lost his faith due to the horrors he experienced as absurd since he never indicates losing his belief in God’s existence or omnipotence despite the unprecedented situation. Rather, R. Shapira maintained an active and passionate relationship with God throughout his sermons and even in his final footnote.

Though R. Shapira would occasionally raise his voice in pain and fear, he always demonstrated a confidence that God could save the Jewish people. R. Shapira therefore did not lose his faith in God, but rather his faith in redemptive history. Abramson writes that “Shapira could no longer fit the suffering of Warsaw Jewry into any previous paradigm of history, least of all suffering as a redemptive response to sin, bringing with it the hope of repentance.”[9] Though He could not comprehend what purpose the Holocaust could possibly have in a divine plan, “he retained, perhaps even fortified, his unshakable faith in the Almighty.”[10]

Shaul Magid’s neighboring contribution, “Covenantal Rupture and Broken Faith in Esh Kodesh,”[11] pushes back against Abramson’s conviction. Magid argues that there is a distinction to be made between R. Shapira’s public portrayal of his faith and his internal struggles, as expressed by his final footnote. Magid further argues that Abramson’s description of R. Shapira’s loss of faith in redemptive history does not negate a broken faith. Such a break is a result of the realization that God will not necessarily save the Jews from a major calamity that they did not do anything as a people to warrant.[12] For Magid, such realizations render faith in a covenantal God broken even if faith in general divinity remains.

As such, in contrast to Abramson, Magid asserts that it does not make sense to distinguish between faith in God and faith in history. Once there is a loss of faith in redemptive history, the realm of any meaningful covenantal theology has been abandoned. After all, it is precisely through the medium of history that revelation plays out. Magid argues that R. Shapira, by admitting that the horrors faced by the Jews of Europe had never been faced before, breaks faith in the covenant itself and preempts the anti-theodicy post-Holocaust theologies articulated most strongly by thinkers such as Rabbis Yitz Greenberg, Eliezer Berkovits, and Richard Rubenstein.

Magid ultimately places R. Shapira’s faith at “the border where blasphemy can coexist with love for God… the God that can be believed in, or loved, after theodicy, after history is de-theologized, is not the same God as before theodicy crumbled with the Ghetto walls or the Great Deportation.”[13] This conclusion paints R. Shapira as “a sign that the impossibility of faith after such a rupture is not dependent on modernity per se but can be gleaned through a stark and honest confrontation with the limitations of tradition.”[14] Though he emphasizes that R. Shapira did not entirely lose his faith in God, Magid makes it clear that he believes that his faith could not possibly have remained unscathed after all that he witnessed.

Magid also notes that R. Shapira does not attempt to bring any traditional texts in justification of his apparent theological paradigm shift. This is, for Magid, a sign that this shift came from a realization of tradition’s inability to withstand the existence of such radical evil. With this realization, attempts at theodicy collapse, leaving nothing to take their place. In Magid’s words, “Disbelief was untenable. But belief as previously defined was no longer possible. God remained, but the covenant, at least as it existed previously, did not.”[15]

Such a description of R. Shapira’s internal psychology is fascinating and powerfully articulated, but is it truly reflective of the lived experiences of human beings? Would one who truly lost their faith in a covenantal God have really followed such a realization with a prayer for speedy salvation? Don Seeman notes in the volume’s closing chapter, “Pain and Words: On Suffering, Hasidic Modernism, and the Phenomenological Turn,” that R. Shapira’s sermons often seem to “serve as little more than a placeholder for contemporary writers’ commitment to their own paradigmatic narratives of meaning in suffering and unbroken faith – or faith’s inevitable demise”[16] and that certainly seems like it may be the case here.

Seeman’s observation can be clearly seen when one compares Magid’s translation[17] of the infamous footnote to Abramson’s[18] in their respective contributions to the volume. Magid stresses the bizarreness and truly unexplainable nature of the reality in which he found himself while Abramson’s translation maintains that the reality is unprecedented but instead uses phrases like grotesque and twisted – words that invoke painful imagery but do not necessarily connote something beyond the pale of expectation, especially during a time of war. While Abramson focuses on disgust, Magid focuses on theological turmoil. Magid, who goes out of his way to paint the vivid picture of a man coming face-to-face with “pure and bizarre evil that erased a covenantal God,”[19] can only translate the note in a way that grants additional legitimacy to his point. On the other hand, Abramson’s own position necessitated de-emphasizing aspects of the note that focused on just how unprecedented the situation was in R. Shapira’s mind – maintaining a neutral theological tone and maintaining a sense of precedence while focusing on the evilness of the Nazi’s actions rather than their bizarreness in comparison to the established covenant.

As noted above, the most obvious question one can raise on Magid’s reading is on the basis of the final line of the footnote, in which R. Shapira continues to pray for God to have mercy and save His people in the blink of an eye. Abramson, who cannot envision R. Shapira experiencing a loss of faith, takes this as a sign of its unshakability. Magid, though, can make no such claim. After spending so many pages attempting to prove that the brunt of the note could only be read as representing a rupture of faith, he has no choice but to quickly describe it as a “final flourish… between pure rhetoric and uttering something that he no longer believed but also could not put to rest.”[20]

But it’s possible to suggest, as Seeman does, that both Magid and Abramson are approaching R. Shapira’s faith in the wrong way by asking “What does R. Shapira believe?” rather than seeking to understand his words as ritual and literary expressions of an ongoing attempt to resist a final collapse.[21] Seeman, for his part, suggests that the text of Aish Kodesh “serves not just to convey a set of doctrines but also to convey vitality for healing and defense of human subjectivity” as well as “to mediate intimacy with unspeakable grief.”[22]

Seeman then clarifies, based on his analysis of R. Shapira’s other writings, that R. Shapira’s faith was less about propositions than about actualizing values. Not that R. Shapira would reject such faith propositions, but his works seem to be more concerned with what Seeman calls “ritual-theurgic”[23] language, as opposed to conventional theology from the start. Indeed, even when R. Shapira describes faith in more traditional language, Seeman notes that he still uses vitalistic language rather than statements of faith. While agreeing with Magid that faith becomes a more insistent and difficult theme in R. Shapira’s writings over time, Seeman points out that Magid’s confident assertion of R. Shapira abandonment of a covenantal theology seems to misunderstand the very nature of his religious experience. As R. Jonathan Sacks wrote, “Faith is not certainty. It is the courage to live with uncertainty.”[24] This idea may very well sum up R. Shapira’s faith better than any assertions of rupture and begs the question of how we today experience faith in our own lives. Is faith a means of connecting to an omnibenevolent God or the map by which we navigate life’s stormy seas? Is it expressed by a series of pronouncements, a commitment to praxis in the face of an uncertain reality, or some combination of each?

Ultimately, we will never truly know the state of R. Shapira’s faith in the last few months of his life. Theology is a tricky subject, made even trickier by the habit of contemporary theologians to read their own preconceived notions into the texts with which they work. Hasidism, Suffering, and Renewal offers an unprecedented lens into multiple different interpretations of one remarkable man’s confrontation with unspeakable evil while also exploring his broader context. As Seeman closes the volume, on this subject “there is no need for uniformity, and the Rebbe of Piaseczno would be the last to demand it. Words or pain, religious teaching and the collapse of language, the text as a vehicle for shared vitality, and threatened loss of humanity are the terrible knife’s edge on which R. Shapira – for a time – stood.”[25] This volume, for the first time, allows us to stand there with him and ask ourselves how we may have responded and how that response can and should color the lives we are lucky enough to be living. The differing contemporary answers to these questions, and how those answers are read back into R. Shapira’s words demonstrate just how much this question still matters to thinkers in our day.

Asking ourselves such a question is particularly needed in this day and age, where it seems too hard to be able to talk about the serious theological questions in our lives. As R. Elliot Cosgrove wrote in 2007 about questions of faith, “there are no easy answers, but a Jewish community that does not ask them will not get very far in its journey.” Hasidism, Suffering, and Renewal does a great service in allowing readers to ask those questions, and challenges us to formulate our own answers along with the volume’s contributors.

Thank you to Rabbi Dr. Ariel Mayse for allowing me to review the book, Lea New Minkowitz for her thoughtful editorial assistance, and Jonathan Engel for copyediting.

1 Moshe Weinberger (adapted by Binyomin Wolf), Warmed by the Fire of the Aish Kodesh: Torah from the Hilulas of Reb Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczna (Feldheim, 2015), 45-46.

2 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, The Lonely Man of Faith (Doubleday, 2006), 2.

3 https://thelehrhaus.com/scholarship/hasidim-and-academics-debate-a-rebbes-faith-during-the-holocauston-facebook-of-all-places/

4 Don Seeman, Daniel Reiser, and Ariel Evan Mayse, Hasidim, Suffering and Renewal: The Prewar and Holocaust Legacy of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira (SUNY Press,:Albany, 2021), 2.

5 Reviewed in this volume by Maria Herman in her contribution, “A New Reading of the Rebbe of Piaseczno’s Holocaust-Era Sermons: A Review of Daniel Reiser’s Critical Edition.”

6 Sefer Aish Kodesh (Hebrew)(Feldheim Publishers, 2007), 211n1.

7 Translation from J. Hershy Worch, Sacred Fire: Torah from the Years of Fury 1939-1942 (Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2004), 307n1.

8 Seeman, Reiser, and Mayse, 295.

11 Reprinted from his 2019 volume, Piety and Rebellion: Essays in Hasidism.

12 R. Shapira’s gradual shift away from traditional theologies of suffering is examined in Erin Leib Smokler’s contribution to the volume, “At the Edge of Explanation: Rethinking ’Afflictions of Love’ in Sermons from the Years of Rage.” R. Shapira’s unconventional theology is also explored in James Diamond’s contribution, “Raging against Reason: Overcoming Sekhel in R. Shapira’s Thought.”

14 Ibid, 313. This sort of argument also appears throughout Magid’s 2013 volume, American Post-Judaism: Identity and Renewal in a Postethnic Society, in which he attempts to articulate a path forward for American Jews when “the myth of tradition no longer operates for them as authoritative.” (11)

15 Seeman, Reiser, and Mayse, 313.

16 Ibid, 333.

17 “It is only the suffering (tsarot) that were experienced until the middle of 1942 that were precedented (hayu kevar). But the bizarre suffering and the evil bizarre deaths (u-mitot ra’ot u-meshunot) that were invented by these evil bizarre murderers on Israel in middle of 1942, according my opinion and the teachings of the sages of the chronicles of the Jewish people more generally, there were none like these before. And God should have mercy on us and save us from their hands in the blink of an eye.” (319)

18 “Only the suffering [tsarot] up to the end of 5702 had previously existed [hayu kevar]. The unusual suffering, the evil and grotesque murders [u-mitot ra’ot u-meshunot] that the wicked, twisted murderers innovated for us, the House of Israel, from the end of 5702, in my opinion, from the words of the sages of blessed memory and the chronicles of the Jewish people in general, there never was anything like them, and God should have mercy upon us and rescue us from their hands in the blink of an eye.” (295)

19 Ibid, 322.

20 Ibid, 323.

22 Ibid, 334.

23 Ibid, 349.

24 Jonathan Sacks, Celebrating Life: Finding Happiness in Unexpected Places (Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019), 83.25 Ibid, 355.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.