Ari Silbermann

Jacob lived in tension, in concealment, and in flight. He entered into the world clinging to his brother and dwelled inside, in tents. His most important encounters take place at night and, to borrow Auerbach’s phrase, he is a character ‘fraught with background.’

He conceals things from his blind father under animal skins and things are concealed from him. He stumbles on a hidden “gateway to heaven,” and fights a mysterious man, not knowing his name.

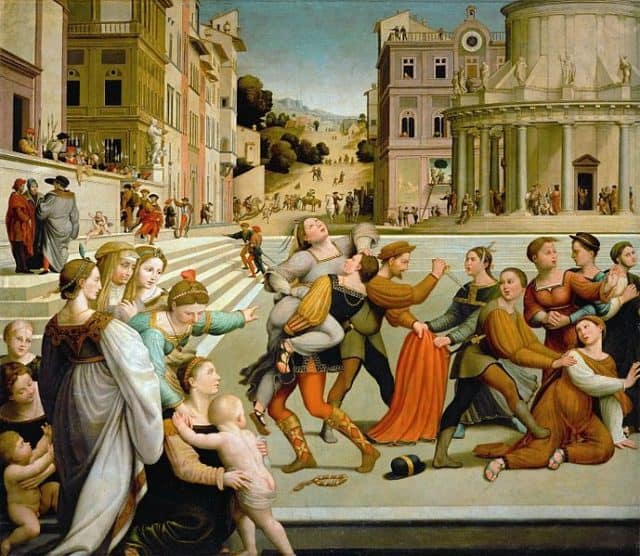

We learn that he was tam – perfect, simple, unblemished – but he is occupied his whole life with efforts to retain Esau’s blessing. He overcomes his demons yet gains a limp – a blemish. With all this seemingly behind him, he arrives at Shechem unblemished, whole. And then he experiences headfirst the rape of his daughter, Dinah. The rape of Dinah and pillaging of Shechem (Gen. 34) is a difficult story with an unclear ending. Was Jacob right to criticize Simeon and Levi, or were they right to defend their sister’s honor? Until Jacob’s contrary blessing of Simeon and Levi, in which Jacob states that he wishes not to enter their council and that they be scattered in Israel (Gen. 49:6-7), their rhetorical question, ‘Shall our sister be made a whore ?’ lingers, powerfully asserting that the brothers may have been right… It is a story of rape, power, and violence, and much ink has been spilled in trying to understand or justify the actions of Dinah’s brothers in response. Many modern writers have noted that in focusing on the brothers’ reaction to Dinah’s rape rather than on her own experience and reaction, we perpetuate the silence enveloping Dinah.[1] She is taken against her will, her brothers negotiate about her and defend her, yet we don’t hear from Dinah herself. Although some modern writers have tried to reconstruct her experience,[2] they face a genuine challenge in doing so.[3] It might be possible to find a window into Dinah’s experiences through another largely silent character in the story, namely her father Jacob. In this article, I will attempt to understand Jacob’s passivity, and in so doing, attempt to reconstruct Dinah’s experiences.

Although Jacob does play a role in the story, he is mostly passive. His sons negotiate and hatch a scheme; Simeon and Levi slaughter the Shechemites while they are in pain, and his sons pillage the city – all seemingly against Jacob’s wishes. Whereas Dinah’s silence is implied, the text highlights that ‘Jacob heard that he [Shechem] had defiled his daughter Dinah; but since his sons were in the field with his cattle, Jacob kept silent until they came home (Gen. 34:5).’ This verse implies that he spoke with his sons about the incident after they returned from the field, but the order of events is blurred by Gen. 34:7 which describes his sons hearing about the incident before their return, ‘Meanwhile Jacob’s sons, having heard the news, came in from the field.’

Jacob’s silence is sharpened by the negotiation scene, in which Shechem and Hamor leave the city to ‘Take for me this girl as a wife.’ (Gen. 34:4). Genesis 34:6 describes Shechem and Hamor coming to speak with Jacob. Instead of the negotiations taking place with Jacob alone, his sons return in the next verse and we have an encounter between the two families – fathers and sons. Shechem and Hamor refer to Dinah in Gen. 34:7 as ‘your daughter’, and in Gen. 34:8 refer to intermarrying between ‘daughters’. Although bat may refer to a young woman and not daughter in the strict sense,[4] the use of the term at the very least suggests that Jacob is part of the conversation. Indeed, in Gen. 34:11 Shechem addresses Dinah’s ‘father and her brothers,’ but only Jacob’s sons respond (Gen. 34:14-17).[5] Thus, at every stage, Jacob seems to be present but silent.

Jacob’s silence here can be contrasted with his strong reactions to another event. Gen. 37:34-35 describes his response upon identifying Joseph’s bloodied coat:

Jacob rent his clothes, put sackcloth on his loins, and observed mourning for his son many days. All his sons and daughters sought to comfort him; but he refused to be comforted, saying, “No, I will go down mourning to my son in Sheol.” Thus his father bewailed him.

Yet the same Jacob who is distraught when his son, Joseph, is supposedly killed is silent when his daughter, Dinah, is kidnapped, degraded, and defiled.[6]

Jacob’s silence has been read in different ways: as a delaying tactic allowing his sons to return and help him, as R. Hirsch suggested, or as the mark of a wise man in the face of the wicked, as Midrash Tanhuma suggests. Or perhaps it was a combination of both of these factors, or, as Malbim explains, Jacob understood that rushing out to fight could not help, since Dinah had already been defiled.

Still, Jacob’s passivity and silence remain puzzling. Why does the Torah not share with us Jacob’s feelings or plans? Why did he not negotiate himself, instead allowing his sons to do so in his place?

The question of Jacob’s passivity also ties in to how Jacob responds to the massacre perpetrated by his sons. He says, “You have brought trouble on me, making me odious among the inhabitants of the land, the Canaanites and the Perizzites; my men are few in number so that if they unite against me and attack me, I and my house will be destroyed.” (Gen. 34:30b) Does Jacob’s pragmatic critique, which seems to be lacking moral censure, imply that he agreed in principle with their actions?[7]

The fact that these questions persist has a lot to do with the silence surrounding Jacob throughout the narrative. According to Midrash Sekhel Tov, the plene spelling of ve-heherish indicates Jacob’s complete and total silence.

I believe that part of the answer to these questions lies in reading Jacob as a secondary victim. Others have assumed that the traumatic nature of the rape affected Dinah and would have led to her fate as a silenced rape victim… As Caroline Blyth writes,

By being denied the opportunity to share her experiences with her family and community, by being faced only with social disgrace, devaluation, and shame, Dinah suffers perpetually the fate of the silenced rape victim, isolated, stigmatised, and deprived of a supportive audience.[8]

Whether her exclusion from the story is related to this we cannot know. However, Jacob’s silence is pronounced because it takes place in the narrative and I suggest that it stems from secondary trauma.[9]

One significant element of trauma is the silence surrounding it. Judith Herman writes in the introduction to her classic study, Trauma and Recovery, that, ‘the ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from consciousness. Certain violations of the social compact are too terrible to utter aloud: this is the meaning of the word unspeakable.’[10]

At times, the silence surrounding rape is even more difficult because the event often takes place in private, in a way that protects the perpetrator and can lead the victim to blame or question themselves.

In traumatic events, and particularly rape, there can also be secondary victims. Researchers note that, following a sexual assault, family and friends may experience emotional distress, including shock, helplessness, and rage, which can parallel the response of the victim. They too may feel violated, guilty, devalued, and may engage in self-blame. As Herman chillingly formulates,

Witnesses as well as victims are subject to the dialectic of trauma…it is even more difficult to find a language that conveys fully and persuasively what one has seen. Those who attempt to describe the atrocities that they have witnessed also risk their own credibility. To speak publicly about one’s knowledge of atrocities is to invite the stigma that attaches to victims.[11]

Jacob has no power, no ability to act, and few options. When Joseph is supposedly taken by a wild animal, there is no stigma at play and so he is free to mourn publicly. But in our case, Jacob does not say anything because he has undergone the trauma of having his daughter raped and kidnapped. He is powerless to stop what is going on, a shepherd in a field he bought from the Hittites, his daughter in their palace, his sons away from home. In many ways, Jacob mirrors Dinah; his silence is also her silence. As his sons negotiate on Dinah’s behalf, they are also negotiating for Jacob. Perhaps like Dinah, Jacob is shocked into silence by the violence committed against his daughter.

The story in Gen. 34 ends with Dinah’s silence, and with Jacob’s. A silence which too often accompanies the victims of violent crimes and their families. As research has shown, secondary victims may experience feelings similar to the direct victim, including feelings of guilt, devaluation, and anger.[12] The shock of a father who questions whether he was to blame, who feels guilty over his inability to act, who may want to act and negotiate on behalf of Dinah but is simply unable to do so.

Just as some traditions blame Dinah for ‘going out,’[13]others blame Jacob, either for not fulfilling his vow (Kohelet Rabbah 5:1), or for his over-cautious treatment of Dinah when meeting Esau.[14] I believe that these sources are best read as expressing Jacob’s and Dinah’s thoughts of self-blame, as they are roiled by the concern that each of them did not do enough to prevent this horrible event from occurring.

Although Dinah’s voice is not heard in the narrative, Jacob’s silence is evidence of his trauma and may also offer a window into Dinah’s pain. Perhaps trying to understand Jacob – and by extension Dinah – can be a starting point which begins to break the silence.

[1] Caroline Blyth, “Terrible Silence, Eternal Silence: A Feminist Re-Reading of Dinah’s Voicelessness in Genesis 34,” Biblical Interpretation 17, no. 5 (September 2009): 483–506.

[2] See Blyth and, for a popular example, see Anita Diamant, The Red Tent (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010).

[3] Meir Steinberg, “Biblical Poetics and Sexual Politics: From Reading to Counterreading,” Journal of Biblical Literature 111 (1992): 480.

[4] Cf. Ruth 2:8.

[5] Although the brothers too use the term ‘our daughter’ in Gen. 34:17, there is a wider usage at play here and actually a wider interplay of the term together with ‘our sister’ throughout the story. For instance, Dinah goes out to see the ‘daughters of the land,’ and the brothers mimic Shechem and Hamor’s deal of intermarrying with each other’s daughters.

[6] Cf. 2 Sam. 13:21 and David’s reaction to Tamar’s rape by Amnon.

[7] Cf. Ramban to Gen. 34:13 for his approach to these issues. Notably, Jubilees 30 has Jacob taking part in the action against the Shechemites.

[8] Blyth, “Terrible Silence, Eternal Silence,” 505.

[9] It is important to note that we need to be cautious in using modern Western psychology to address issues in the Biblical text. Freud’s Moses and Monotheism is an extreme case in point and should serve as a warning.

[10] Judith Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence — From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (Basic Books, 2015), 1.

[11] Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery, 1.

[12] See for instance P. N. White and J. C. Rollins, “Rape: A Family Crisis.,” Family Relations 30 (1981): 105. In this sense, the violent response of the brothers is also a characteristic response. Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery, 65 notes that such reactions can sometimes hamper the ability to discuss the trauma. She brings the following testimony of a rape survivor and her husband’s reaction, “ ‘When I told my husband, he had a violent reaction. He wanted to go after these guys. At the time I was already completely frightened and I didn’t want him exposed to these people. I made myself very clear. Fortunately, he heard me and was willing to respect my wishes.’” Quoted by Lewis Herman from “If I can survive this….” (Cambridge, MA, Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, 1985). Videotape.

[13] Gen. Rabbah 80:1.

[14] Gen. Rabbah 76:9.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.