Chesky Kopel

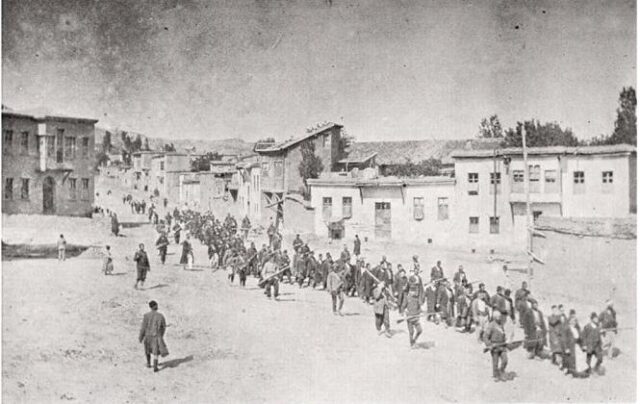

During World War I, the Turkish nationalist leadership of the Ottoman Empire portrayed ethnic Armenians as a fifth column, aligned with Russia against the interests of the Empire. The incitement reached a murderous frenzy in the spring of 1915, when the Ottoman military began to round up and deport Armenian leaders and intellectuals from Constantinople to concentration camps in eastern Turkey. These deportations were followed by forced imprisonment of millions in labor camps, massacres of Armenian men, death marches of Armenian women, children, and elderly people into the Syrian desert, and widespread sexual abuse. By 1922, an estimated 1.5 million Armenian people had been killed.[1] In Jewish communities, the subject of the Armenian Genocide is often raised in the context of, and as providing context for, the Holocaust—our own national calamity. However, a 1915 spy cable, considered in detail below, provides a provocative, contemporary Jewish perspective on the events in Armenia.

Background

Most historians of the war period consider the Ottoman atrocities to meet the legal definition of genocide. But this scholarly near-consensus has not translated into political consensus. The Republic of Turkey, which succeeded the fallen Ottoman Empire following the war, denies the occurrence of any genocide and pressures other governments to adopt the same position, sometimes as a precondition for the maintenance of diplomatic relations.[2] This strategy has succeeded to a surprising extent. For instance, the government of Israel has consistently declined to recognize the Armenian Genocide, despite longstanding support for recognition by politicians as ideologically disparate as the late Yossi Sarid of Meretz, Ayelet Shaked of Yamina, and current president Reuven Rivlin of the Likud.[3] In the United States, although resolutions in support of recognition passed both the Senate and the House of Representatives with resounding bipartisan support in 2019, the Trump Administration publicly rejected them.[4] (The White House’s position, too, is bipartisan; President Obama declined to describe the events as genocide despite promising to do so in his 2008 election campaign.)[5] Even major Jewish communal organizations in the United States, among them the Jewish Federations of North America and the Orthodox Union, have not taken a public position on the Armenian Genocide.[6]

For Jews today, the historical meaning of the Armenian Genocide is inextricably bound with that of the Holocaust. We know that the Ottomans’ success emboldened the Nazis; to justify his deadly pursuit of “living space” for Germans, Hitler reportedly said, “Who today remembers the Armenian extermination?”[7] And Jewish leaders frequently invoke the Holocaust experience as a motivation for extending support to Armenians in their pursuit of genocide recognition. In a 2015 resolution, the Jewish Council for Public Affairs declared, “The Jewish communities, as the targets of one of the worst genocides of the twentieth century, have a bond with the Armenian people here in the United States and abroad. We have a moral obligation to work toward recognition of the genocide perpetrated against the Armenian people.”[8] On the Knesset floor in 2018, then Meretz chairwoman Tamar Zandberg similarly explained her motion in support of recognition: “Both in our case and the Armenians’, the great powers knew about the murders and did nothing to stop them. This is why we are saying to the world, never again. Never stand on the sidelines again….”[9]

However, Jews learned of the Ottoman atrocities, and articulated Jewish reactions to them, long before the Holocaust began. During World War I, when news reports of the killings reached the United States, renowned Reform rabbi and public figure Stephen Wise emerged as a leading advocate for U.S. intervention on behalf of the Armenians. In a 1918 letter to his wife Louise, Rabbi Wise explained, “I would speak with the tongue of angels for the Armenians and against their oppressors. If a Jew is not to be the champion of any wronged people, who should be?”[10] At the same time, in the Zionist Yishuv in Ottoman-controlled Palestine, a small network of amateur spies called Nili sought with desperation to assist the Armenians. The documents left behind by Nili, explored further below, express a uniquely Jewish imperative to act on behalf of Armenia and mourn its dead.[11]

Nili’s Struggle for Armenia

Nili—the name is a Hebrew acronym for “netzah Yisra’el lo yeshaker”—“the Eternal One of Israel will not lie” (I Samuel 15:29)—undertook espionage operations to assist the British war effort against the reigning Ottomans. Their ultimate goal was to enlist British support for the establishment of a Jewish nation-state in Palestine following a victory by the Allies (including the United Kingdom) over the Central Powers (including the Ottoman Empire). The group, which included only a few dozen members, based its operations in Zikhron Ya’akov and acted without any authority from the formal Zionist leadership in Palestine.[12]

Nili’s founders, 39-year-old agronomist Aaron Aaronsohn and his 25-year-old assistant Avshalom Feinberg, acted on their impression that British forces in the Middle East lacked clear intelligence about the facts on the ground in Palestine. After several unsuccessful attempts to contact the British military in Egypt, Aaronsohn managed to travel to London and coordinated a bold communication strategy. Between February and September 1917, the Royal Navy’s HMS Managam (nicknamed “Menachem” by the Jewish spies) made frequent secret moonless night landings on Atlit beach, near Aaronsohn’s experimental farm that had come to serve as an ad hoc base for espionage operations. During the Atlit visits, Nili members transmitted intelligence they collected concerning Ottoman troop movements—one of their leading field spies was Ottoman military officer Eitan Belkind—and oppressive government acts like the 1917 expulsion of Jews from Tel Aviv. The Managam also smuggled in financial assistance for the Yishuv sent by Jews in Allied countries, which had previously been subject to an Ottoman wartime embargo.[13]

The plight of the Armenians was a major concern and rallying cry of the Nili members. Two of them left eyewitness accounts of the atrocities: Aaron Aaronsohn’s sister Sarah Aaronsohn, who assumed a leadership role in the organization during Aaron’s stays in Egypt, described seeing piles of corpses of massacred Armenians during her late 1915-early 1916 journey from her husband’s home in Constantinople back to her family’s home in Zikhron Ya’akov. (Unfortunately, our only written account of what Sarah saw is secondhand, filtered through the words of her brother.)[14] Belkind similarly reported witnessing massacres during his Ottoman military service (although his account was first published in his memoirs 60 years later and may have been influenced by Holocaust imagery).[15] The Armenian Genocide appears many times in Nili’s records and communications: sometimes in terms of Jewish self-preservation, as in Aaron Aaronsohn’’s November 1916 warning to his British handlers that the Jews would be “next in line”;[16] sometimes in terms of solidarity against a common oppressor, as in Aaron’s plea for “the poor nations and races under the Turkish despotism, be they Armenians, Greeks, Jews, or Arabs”;[17] but other times in terms of deep-rooted empathy informed by Tanakh and Jewish historical memory. Though many Nili texts exhibit this empathy, few are as striking as this passage in Feinberg’s November 22, 1915 intelligence report to British intelligence officer Lieutenant Leonard Woolley:

My teeth have been ground down with worry. Whose turn is next? When I walked on the blessed and holy ground on my way up to Jerusalem, and asked myself if we were living in the modern era, in 1915, or in the days of Titus and Nebuchadnezzer? And I, a Jew, forgot that I am a Jew (and it is very difficult to forget this “privilege”); I also asked myself if I have the right to weep “over the tragedy of the daughter of my people” only, and whether Jeremiah did not shed tears of blood for the Armenians as well?!

Because after all, inasmuch as the Christians – of whom not a few sometimes boast that they have a monopoly over the commandments of love, mercy and brotherhood – have been silent, it is imperative that a son of that ancient race which has laughed at pain, overcome torture and refused to give in to death for the last two thousand years, should stand up…It is imperative that a drop of the blood of our forefathers, of Moses, of the Maccabeans who rose up in the scorched land of Judea, of Jesus who prophesied on the banks of the blue sea of Galilee, and the blood of Bar Kochba… That a drop of the blood which was saved from annihilation should rise up and cry: Look and see, you whose eyes refuse to open; listen, you whose ears will not hear, what have you done with the treasures of love and mercy which were placed in your hands? What good have rivers of our spilled blood done? How have you realized your high ideals in your lives?[18]

Feinberg’s report, originally written in French, apparently reached Lieutenant Woolley in Cairo, but it did not immediately lead to further contact between Nili and the British military. How Woolley reacted to an intelligence report laden with impassioned Biblical allusions is unknown, but it is our great fortune today that the report’s contents survive.

In this passage, Feinberg strives to convey to Woolley a uniquely Jewish perspective on the Armenian Genocide. However, this Jewish perspective is not static; it evolves, both emotionally and logically, over the course of two poignant paragraphs. At the outset, Feinberg worries about his own people—“Whose turn is next?”—mourning their possible fate with the words of Lamentations, the quintessential work of mourning. His “teeth have been ground down with worry” (Cf. Lamentations 3:16). He sees the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem by Babylonian Emperor Nebuchadnezzar—recounted in Lamentations—and the destruction of the Second Temple by Roman Emperor Titus, and he fears a similar calamity.

Feinberg then begins to look beyond his self-interested perspective, to “forg[e]t” his Jewishness. He considers that his weeping “over the tragedy of the daughter of my people” (Lamentations 2:11, 3:48, 4:10) must be accompanied by weeping for the murdered Armenians. To ground this empathy in the Jewish tradition of mourning, the letter alludes to the midrash according to which Jeremiah’s lamentations reach beyond his contemporary moment and encompass the tragedies of the future: “‘Bakhoh tivkeh ba-laylah’ [‘she surely weeps at night’]—why does the verse include two weepings [i.e., two iterations of the Hebrew word for weeping]? Rabbah said in the name of Rabbi Yohanan: one for the First Temple and one for the Second Temple” (Sanhedrin 104b). In Feinberg’s telling, just as Jeremiah shed tears for the Second Temple, which was built and destroyed long after his death, so must he have shed tears for the mass murder of Armenians over two thousand years later. In this most complete form of empathy, Jewish national mourning is not simply a model for mourning the Armenians, it includes mourning the Armenians.

The mourning gives way to righteous anger. Feinberg accuses the Western Christian powers of neglecting their supposed commitment to “love, mercy and brotherhood,” as far as the Armenians, themselves a Christian minority, were concerned. His solution is to re-appropriate the nominally Christian ethic of empathy as something essentially Jewish. The Christians’ “monopoly” is broken, their way has become the way of idols “whose eyes refuse to open” and “whose ears will not hear” (Cf. Psalms 115:5-6, 135:16-17), and “Jesus who prophesied on the banks of the blue sea of Galilee” reemerges as a Jewish “forefather” inspiring Jewish action on behalf of others. Feinberg foresees that he may be called to give his life for others as Jesus was purported to do, invoking Jesus’ announcement of his fate “on [my] way up to Jerusalem” (Cf. Mark 10:32).

After traveling through worry, weeping, and anger, Feinberg arrives finally at action. He no longer derives his inspiration from Jeremiah, the prophet of mourning, but rather from the military leaders of ancient Israel: Moses, the Maccabees, and Bar Kokhba. (The one arguable Lamentations reference in this part of the passage—“look and see” (Cf. Lamentations 1:12)—is not an expression of lamentation but a demand that the peoples of the world do not look away from the tragedy of the Armenians).

Feinberg did ultimately give his life for the Nili cause. In January 1917, out of frustration over the failure to establish regular contacts with the British—the Managam routine had yet to begin—Feinberg set out to cross the Sinai Peninsula on foot with fellow spy Yosef Lishansky, in order to reach British Egypt. On January 20, Feinberg and Lishansky were discovered by Bedouins loyal to the Ottoman Empire. During a firefight with Ottoman officers, both Lishansky and Feinberg were wounded; Lishansky escaped first to Egypt and then back to Palestine, and Feinberg died in the Sinai. His body was not discovered until Israel conquered the peninsula in 1967.[19]

Feinberg’s death played a role in the violent fall of Nili. In September 1917, a carrier pigeon carrying an encrypted message from Sarah Aaronsohn to offshore British contacts was intercepted on the property of Ahmad Bey, the Ottoman governor of Caesarea. Although the Ottomans could not interpret the message, it heightened their awareness of possible espionage activities in Palestine. Shortly afterward, Nili spy Na’aman Belkind (Eitan’s brother) sought to cross the Sinai on foot in an effort to investigate Feinberg’s disappearance. Belkind was arrested and divulged information about Nili under the pressure of interrogation. In October 1917, Ottoman forces surrounded Zikhron Ya’akov. Sarah Aaronsohn committed suicide to avoid capture, and Lishansky and Na’aman Belkind were hanged in Damascus.[20]

More than a century later, the example of Nili and the searing words of Avshalom Feinberg now serve to rebuke the Jewish institutions, including the Federations, the Orthodox Union, and, by far most importantly, the government of the State of Israel, for their failure to honor the tragic history of the Armenians out of deference to geopolitics. Perhaps needless to say, if a western government were to deny the historical consensus of the Holocaust in order to improve relations with, for instance, Iran, the decision would be condemned as beyond the pale of moral society. But we need not search for analogies in modern history to make this point; Feinberg’s Biblical sensibility challenges us to consider a particularized empathy that is deep-rooted in Jewish national memory. Whether or not Jeremiah foresaw the Armenians, he cried for them.

[1] John Kifner, “Armenian Genocide of 1915: An Overview,” The New York Times, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/ref/timestopics/topics_armeniangenocide.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See Raphael Ahren, “Why Israel still refuses to recognize a century-old genocide,” The Times of Israel (April 24, 2015), https://www.timesofisrael.com/why-israel-still-refuses-to-recognize-a-century-old-genocide/; Aaron Kalman, “MKs say high time for recognition of Armenian genocide,” The Times of Israel (April 23, 2013), https://www.timesofisrael.com/mks-say-high-time-for-recognition-of-armenian-genocide/.

[4] Jennifer Hansler, “Trump administration won’t call mass killing of Armenians a genocide despite congressional resolutions,” CNN (December 17, 2019), https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/17/politics/trump-administration-armenian-genocide/index.html.

[5] Nahal Toosi, “Top Obama aides ‘sorry’ they did not recognize Armenian genocide,” Politico (January 19, 2018), https://www.politico.com/story/2018/01/19/armenian-genocide-ben-rhodes-samantha-power-obama-349973.

[6] See Eric Cortellessa, “Why some US Jewish groups now recognize the Armenian genocide, and others don’t,” The Times of Israel (December 13, 2019), https://www.timesofisrael.com/why-some-us-jewish-groups-now-recognize-the-armenian-genocide-and-others-dont/.

[7] Kevork B. Bardakjian, “Hitler’s Armenian-Extermination Remark, True or False?,” The New York Times (July 6, 1985), https://www.nytimes.com/1985/07/06/opinion/l-hitler-s-armenian-extermination-remark-true-or-false-103469.html.

[8] “Resolution on Armenian Genocide,” Jewish Council for Public Affairs (October 16, 2015), http://engage.jewishpublicaffairs.org/p/salsa/web/blog/public/?blog_entry_KEY=7642.

[9] Lahav Harkov, “Knesset approves motion on recognizing Armenian Genocide,” The Jerusalem Post (May 23, 2018), https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Knesset-approves-motion-on-recognizing-Armenian-Genocide-558191.

[10] Claire Mouradian, “Jewish Coverage of the Armenian Genocide in the United States,” in Mass Media and the Genocide of the Armenians: One Hundred Years of Uncertain Representation, eds. Joceline Chabot, Richard Godin, Stefanie Kappler, and Sylvia Kasparian (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 221n1.

[11] In an influential 1995 book, Israeli historian Yair Auron argued that the people and institutions of the Yishuv received extensive, timely information on the events of the Armenian Genocide and largely reacted with apathy. In Auron’s telling, the Nili spies represented the exception to the disappointing general rule of the time and place. For the English edition of the book, see Yair Auron, The Banality of Indifference: Zionism and the Armenian Genocide (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2000).

[12] Chen Malul, “N.I.L.I.’s Story Told Through the Diary of the Man Who Gave It Its Name,” The National Library of Israel (November 5, 2017), https://blog.nli.org.il/en/nili/; “Mahteret Nil”i,” Beit Aaronsohn-NILI Museum, https://www.nili-museum.org.il/%d7%9e%d7%97%d7%aa%d7%a8%d7%aa-%d7%a0%d7%99%d7%9c%d7%99/.

[13] Malul, ibid; “Mahteret Nil”i,” ibid; Hershel Edelheit & Abfaham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary (New York: Routledge, 2018), 358-359.

[14] Yair Auron, “Jewish Evidences and Eye Witness Accounts About the Armenian Genocide During the First World War” (lecture, T.C. Istanbul Universitesi International Symposium: The New Approaches to Turkish-Armenian Relations, March 15-17, 2006) (“Auron Lecture”), 11-15, http://www.ihgjlm.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Jewish_Evidences_Part2.pdf.

[15] Ibid, 15-17.

[16] Ibid, 19.

[17] Auron, The Banality of Indifference, 384.

[18] “Auron Lecture”, 6-10.

[19] Israel Defense Ministry, “Avshalom Feinberg,” Yizkor (Hebrew), https://www.izkor.gov.il/%D7%90%D7%91%D7%A9%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%9D%20%D7%A4%D7%99%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%91%D7%A8%D7%92/en_e32f6da38c0e141230be835f6610b805 (See also the English biography at: http://www.zionism-israel.com/bio/biography_avshalom_feinberg.htm); Israel Defense Ministry, “Yosef Lishansky,” Yizkor (Hebrew), https://www.izkor.gov.il/%D7%99%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%A3%20%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%A1%D7%A7%D7%99/en_06b29ac212446b4341f2ff92c3ead817.

[20] “Mahteret Nil”i,” op cit; “Havrei Nil”i,” Beit Aaronsohn-NILI Museum, https://www.nili-museum.org.il/%d7%97%d7%91%d7%a8%d7%99-%d7%a0%d7%99%d7%9c%d7%99/.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.