AJ Berkovitz

Ever open to the back of ArtScroll’s Stone Chumash? Displayed on those final pages is a genealogical table available for writing the names of your parents, grandparents, children, and grandchildren. With this chart, ArtScroll preserves a pre-modern tradition, what I will call “the Living Bible.” This tradition was fundamentally rooted in the material production of the Bible in the Middle Ages. If you wanted to read scripture before the invention of print, your only recourse was to texts written by hand—manuscripts (manu=hand; scriptus=written). One would require quality parchment, a ready scribe and—depending on your tastes—an illustrator.

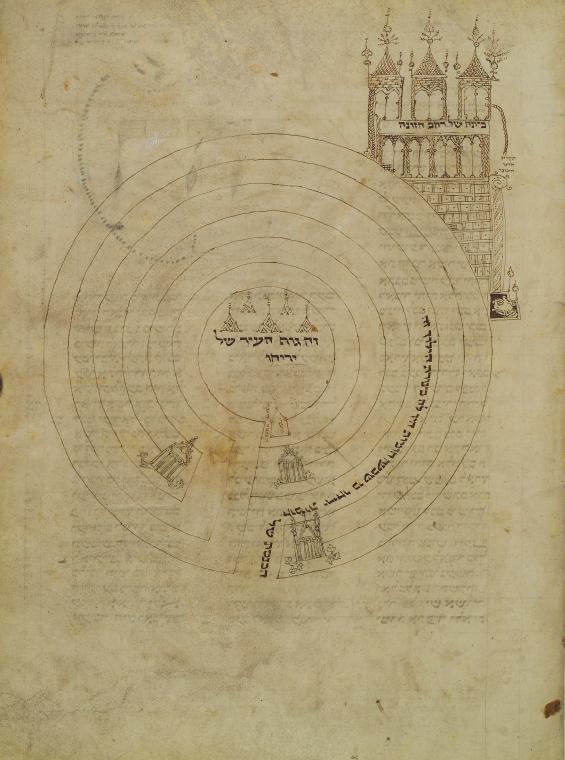

Jericho: Town Plan and Rahab’s House, Xanten Bible, 1294

Jericho: Town Plan and Rahab’s House, Xanten Bible, 1294

They were not cheap. In the fourteenth century, a parchment Tanakh was sold by Solomon ben Joseph Kohen to the Florentine humanist Giannozzo Manetti for the price of 21 large florins (worth about $8,400 in today’s dollars). These expensive products became magnets for additions of all sorts, from short comments to complete documents, both related and unrelated to the actual biblical text. These Living Bibles, transformed and updated with use and reuse, afford us a passing glimpse into the life and times of those who produced and read them.

In this brief essay, I will explore the contours of some Bible manuscripts from the Vatican Library—the true hidden treasures housed in Papal Rome. In particular, I will examine two features of Living Bibles: marginalia and owner notes. I hope to excite and encourage further exploration into this underappreciated cache of Jewish history, a task made easier by an accessible manuscript catalogue and free online digitization.

Marginalia

How do you read a book? One tried-and-true method is to read with pen in hand. Find a clever or curious passage? Underline it. Wish to “dialogue” with the author? Write in the margins. Words produced through this last form of interacting with a book are often called “marginalia.” Marginalia transform an unadorned object into living text, and tell us much about how owners actively engaged with the books they purchased.

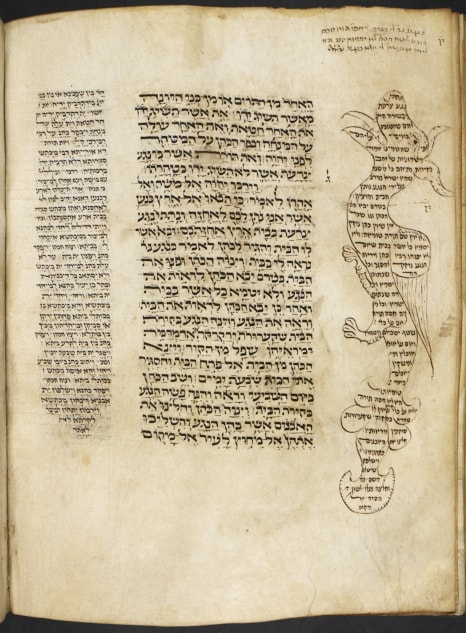

An example of marginalia can be found on the top-right hand side of this page from the Multi-Scribe Pentateuch, 14th century, France. On the outer side of the page is Rashi’s commentary in the shape of a dragon.

An example of marginalia can be found on the top-right hand side of this page from the Multi-Scribe Pentateuch, 14th century, France. On the outer side of the page is Rashi’s commentary in the shape of a dragon.

The Bible manuscripts of the Vatican Library are replete with marginalia. For the most part—like our notes—they are brief. A fourteenth century Italian copy of Ketuvim contains several notes and explanations in the margin. Among them are translations of difficult Hebrew words into Italian, the mother tongue of the scribe and owner. Similar is the case of a thirteenth century French manuscript that contains Torah, Megilliot, and the Haftarot. In this text, however, multiple different handwritings appear in these notes. Our manuscript was subject to multiple readers, perhaps part of the same family, or passed from one owner to another. In all of these instances, this sort of notetaking demonstrates that readers and learners actively engaged with the text in front of them.

Our French manuscript points to another use of marginalia in the Medieval bible: the commentary. In the Middle Ages, Jewish Bible commentaries often existed as independent entities that one would read next to texts of the stand-alone Bible. In modern terms, it was more like consulting a copy of Bekhor Shor than reading Rashi on the bottom of the page in a printed Humash. Manuscript marginalia presented a middle ground. Short extracts from the commentary of Ibn Ezra line the margins several times in our French manuscript. Were these comments that the owner particular cherished? Did he or she append them to sections that felt particularly difficult or interesting?

Commentary marginalia were not limited to short excerpts. A fourteenth century German copy of Torah-Megillot-Haftarot, which seems to have been used as a tikkun, contains Rashi’s commentary from Genesis 1:1 until Numbers 23:10. More surprising, however, is the copy of the Bible that ultimately ended up in the possession of the Florentine diplomat, Giannozzo Manetti. The upper and lower margins of roughly 80 pages of this manuscript are filled with the entirety of Rabbi David Kimhi’s Sefer Ha-Shorashim, an early Hebrew dictionary. Given this interest in producing a single work containing both text and interpretive tool, we might call this Bible manuscript a veritable “Study Bible.” Unlike modern study Bibles, however, these manuscripts were produced for individuals, inflected for their tastes, and constantly updated with use.

Ultimately, marginalia contain the now-distant voices of actual readers, and demonstrate how they interacted with the text they encountered.

Owner’s Notes

The Bibles of the Vatican library are also “alive” and “living” because of the various notes and documents that owners appended to their manuscripts. The most common note in these manuscripts will not surprise; in fact, it exemplifies the same activity that many perform upon acquiring a book: I refer to the act of writing our name. Unlike modern practice, however, new owners did not necessarily efface the names of their predecessors. A thirteenth century Italian Tanakh contains the names of several owners on the first page of the text. They include: Yoav ben Yehiel, Avraham Yehiel Yaakov, Eliyahu ben Yehuda HaRofeh, Yosef ben Shalom, and Shlomo ben Yosef HaKohen. Chains of tradition live in the movement of texts from seller to buyer, who may in turn become a seller.

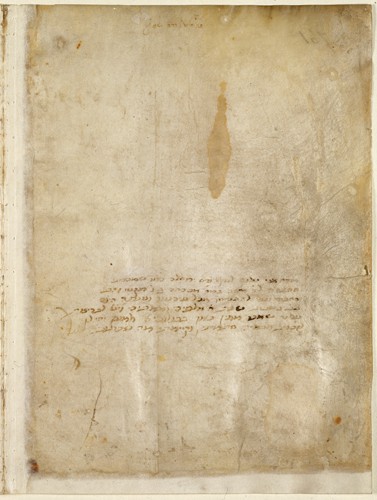

Ownership Note, Xanten Bible, 1294

Ownership Note, Xanten Bible, 1294

Oftentimes, these expensive books did not merely record the name of the new owner, but also the bill of sale. Valuable objects required proof of purchase. Another thirteenth century Italian Tanakh demonstrates the production and movement of a Bible manuscript. According to the colophon, a scribal note appended to the end of a document, the manuscript was copied by Yekutiel ben Yehiel for Menahem ben Moshe Ha-Dayyan on August 13, 1286. Sometime before the year 1432, the manuscript made its way into the possession of a certain Netanel. Netanel bequeathed the manuscript to his son-in-law, Moshe ben Yekutiel, upon his deathbed as a “complete gift.”

The story does not end here. The bill of sale written in this manuscript records that Moshe, on 15 Elul 1432, sold the manuscript to Yaakov ben Avraham HaRofeh for the price of 42 gold ducats. Moshe and two witnesses—Yosef ben Shmuel and Menahem ben Daniel—signed the document. The buyer, Yaakov, wrote an additional note that he purchased the text at the request of his son-in-law, Shabbetai ben Yekutiel, and that he was repaid by Shabbetai on 3 Sivan 1433.

An entry at the end of the manuscript continues the tale. Over 100 years later, in 1563, the daughter of Moshe of Porto and her sister, Grazietta, sold the manuscript to Moshe ben Ovadiah in the presence of Shmuel ben Yehiel. Ultimately, it wound up in the Vatican library. Unlike the modern trade paperback book, these medieval manuscripts lived long and fruitful lives. They were read by generations of Jews.

Conclusion

To be a “people of the book” in the Middle Ages, Jews needed to actively produce and purchase manuscripts. These were pricey investments, but ones that yielded long-term fiscal and spiritual dividends. In certain circles, purchasing a book was elevated to the level of mitzvah. A story in Sefer Hasidim makes this all-too-clear:

One woman was charitable but had a husband who was stingy, who did not wish to buy books or give charity. And when her time came to perform her [monthly] immersion she did not wish to do so. He asked her, ‘Why do you not immerse yourself?’ She said: I will not immerse myself unless you agree to buy books and give money to charity. And he did not want to do so, and she refused to immerse until he would agree to buy books and give charity. He complained to the sage about her, who told the man: May your wife be blessed that she forced you to do a mitzvah (§670, Wistinetzki edition, translation by Avraham Grossman, italics mine).

All this has merely scratched the surface of what the Vatican library has to offer students of Jewish history and literature. The true treasure of the Vatican is the tremendous output of the Jewish people. This cache of manuscripts, once great, sits lonely. It calls for readers to reintegrate its manuscripts into Jewish thought and culture. Can we turn dead books back into living ones?

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-100x75.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.