Oran Zweiter

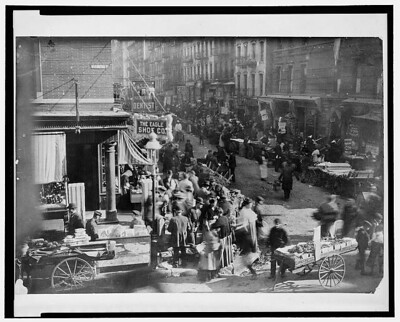

The first collection of she’elot u-teshuvot (rabbinic responsa to communal queries) printed in the United States, Ohel Yosef by Rabbi Yosef Eliyahu Fried (1903), provides a glimpse into immigrant life on New York’s Lower East Side at the turn of the twentieth century.[1] His series of teshuvot (responsa) related to Shabbat provide a vivid view of the dynamics of the Lower East Side community at the time, as well as the thought processes of a posek grappling with these communal dynamics. The responsa tell the story of how Jews on the Lower East Side observed Shabbat to varying degrees, or not at all. In his answers to the halakhic challenges with which he was faced, one encounters Rabbi Fried carefully navigating two motivations in tension with one another: finding leniencies to keep everyone as close to observance and to the community as possible, yet not being so overly lenient as to compromise the integrity of Shabbat. Rabbi Fried’s responsa illustrate the efforts this early American posek took in order to maintain the cohesiveness of his community in light of the varying levels of halakhic observance within it.

Rabbi Fried arrived in New York City from Saukenai, Lithuania in 1891[2], taking up residence on the Lower East Side, and eventually began delivering classes at the Eldridge Street Synagogue.[3] Ohel Yosef contains responsa on a variety of topics relevant to the lives of newly-arrived Eastern European immigrants adapting to life in New York City. Halakhic questions he dealt with touch on the propriety of using dance halls for prayer services, the permissibility of building a sukkah on a fire escape, and whether one can consume milk that was produced under government supervision but without rabbinic supervision (interestingly, he permits consumption of such milk, albeit reluctantly, approximately fifty years before Rabbi Moshe Feinstein’s well-known and influential ruling on the topic).

Rabbi Fried’s concern with maintaining communal cohesion is reflected in his attitudes towards both non-observant Jews as well as observant ones. In a responsum on the topic of whether non-observant Jews can perform the mitzvah of birkat kohanim (the priestly blessing, recited on holidays in Ashkenazic congregations), Fried begins by presenting his overall approach to Jews who are not observant and how the community and its leaders should relate to them. In Fried’s view, most Jews in his time who left observance did so under pressure to earn a living, but fundamentally still believed in God and the Torah. As evidence of this assertion, Fried notes that during the High Holidays these people not only come to synagogue, but in fact ask God for forgiveness, showing that Torah observance is not something they outright reject but rather something they feel forced to violate. Even though one cannot rely upon these Jews in matters such as kosher food preparation, they should not be distanced further from observance, but rather kept in the fold as much as possible. With regard to observant Jews, Rabbi Fried makes it clear that he respects and admires their observance, placing a high value on attempts to keep halakha even if they may be less than ideal. Fried was asked, for example, about the propriety of returning a temporarily-moved vessel of hot water to a gas stovetop on Shabbat when the stove is covered with a blech (Yiddish for “tin,” referring to a metal sheet that acts as a spacer between the heat source itself and the pot or kettle on the stove). Citing earlier authorities, Fried concludes that although one may consider ruling stringently in this case – Ashkenazic practice permits returning cooked solids to a blech, on the principle that they fundamentally cannot be “cooked” a second time, but liquids are considered cooked anew each time they are reheated – one need not do so. Since this is an example of the Jewish people’s steadfastness about observing the commandment of oneg Shabbat (enjoying physical pleasures on Shabbat), one should allow them to continue the lenient (for Ashkenazim) practice of returning water to a covered gas stove. These general approaches towards both the non-observant and observant elements of the immigrant community on the Lower East Side animate Rabbi Fried’s responsa, particularly those related to Shabbat.

In two consecutive passages (Ohel Yosef, responsa 6 & 7), Rabbi Fried takes up the question of benefiting from the products of forbidden labor performed by a Jew on Shabbat. In the first case, he was asked, regarding bakeries which employ Jews on Shabbat, whether one can consume their bread after Shabbat. In the second case, he was queried regarding the general issue of using an item that was carried by a Jew from a private domain to a public domain on Shabbat. In both cases he rules leniently, following the majority halakhic opinions, but he adds caveats which most effectively reflect his approach to these matters. Regarding the bread baked by Jews on Shabbat, Fried states that despite it being fundamentally permitted to consume the bread, the rabbis of the community should ideally adopt the minority view and limit consumption of the bread until late enough on Saturday nights that it could have been produced after Shabbat (known in halakha as be-ke’dei she-ya’asu, “how long it would have taken them,” a principle that normally only applies to benefiting from work performed by a non-Jew on a Jew’s behalf on Shabbat). This, in Fried’s view, would serve as a penalty and constraint against the immediate profits the bakeries would be capable of making. Similarly, in the case of a Jew carrying from a private domain to a public one, Fried recognizes that the majority view follows the lenient approach allowing one to benefit from the act, since no physical change has occurred to the item. Nonetheless, he states that one should follow the minority view and prohibit benefiting from the item, reasoning that ruling stringently in this case will prevent the community at large from treating Shabbat lightly. In both cases, one sees the balance Rabbi Fried is trying to strike. He recognizes the technical correctness of the lenient majority opinion, but takes into account the specific needs of his community, where it was critical to maintain the general framework of Shabbat observance.

While in the just-discussed cases Rabbi Fried was trying to strike a balance by incorporating more stringent approaches into his rulings, two other cases are examples of thorough leniency. Regarding the question of Jews riding the ferry across the river on Shabbat, as well as the question of carrying within an apartment building occupied by both observant and non-observant Jews, Fried rejects any argument that may interfere with the common practice amongst Jews on the Lower East Side.

Regarding riding the ferry, Fried comments at the start of his analysis that many people in the community are lenient about riding the ferry and are not concerned with any halakhic issues, including that of tehumin (traveling beyond the halakhically-dictated perimeter on Shabbat). Rabbi Fried raises all of the possible halakhic concerns with riding the ferry and systematically rejects each and every one of them. Relying upon earlier authorities, such as Hatam Sofer, Fried rules that there are no concerns of tehumin or carrying from one domain to another. Furthermore, since most of the passengers are not Jewish and the ferry is operated by non-Jews, it is permissible for Jews to ride if needed. While this last point, restricting his allowance to cases of need, may be taken as a qualifying stringency, Fried’s expansive understanding of what is considered a legitimate need, as well as his aforementioned rejection of other grounds for stringency, are reflective of his outright lenient approach to this issue.

In a case that perhaps carries the most weight in terms of the relationship between the observant and non-observant people in the community, Rabbi Fried again ruled outright leniently, thereby preventing conflict between these two communal elements: people literally living next door to each other. The question he was asked was about carrying within an apartment building inhabited by both observant and non-observant Jews. The Talmud (Eruvin 61b) states that if one lives in a common space with either non-Jews, or Jews who do not acknowledge the efficacy of an eruv (the mechanism by which different domains are considered halakhically joined, allowing one to carry amongst them), one is not permitted to carry from their home to the courtyard, i.e. into the common spaces. Commentaries on the Talmud (Rashi there, s.v. Oser Alav) qualify this ruling, explaining that the observant Jews can still carry into the common areas if they perform a sekhirat reshut: leasing the common areas from the other parties. The problem addressed by Rabbi Fried is that some non-observant Jews in his community were antagonistic towards their Shabbat observing coreligionists, and would therefore not comply with the sekhirat reshut process. Recognizing that this issue could cause intractable challenges, Rabbi Fried again dismisses any arguments towards stringency. His lenient opinion, based on earlier sources, is two-pronged. Firstly, he argues that even Jews who are known to be non-observant of Shabbat should very rarely be formally classified with the status mehallelei Shabbat be-farhesya (public violators of Shabbat), which means they are not individuals with whom one is obligated to perform sekhirat reshut. Additionally, Fried argues, one can assume that the owner of the building did not rent apartments to people thinking that they would have the opportunity or ability to restrict the other tenants from carrying in the building’s common spaces; willingness to recognize the efficacy of an eruv might be considered implicit in the terms of residency. With these arguments Rabbi Fried is not only able to help people observe Shabbat in a less restrictive way, but more broadly, he is able to prevent friction between Jews residing in the same apartment building. By carefully addressing this particularly thorny issue, Rabbi Fried is able to thwart conflict in an effort to maintain cohesion between opposing members of the Lower East Side community.

In his book of sermons, Alumat Yosef (18-21), Rabbi Fried asserts that observance of Shabbat has sustained the Jewish people throughout their journeys in exile. Furthermore, Fried emphasizes that Shabbat is a unique gift given only to the Jewish people, and it is something the people must cherish by observing it. These complementary values of observance and peoplehood are what informed Rabbi Fried’s halakhic approach to Shabbat in the Lower East Side community. They are telling, not only as they pertain to Shabbat specifically, but as they reflect the attempts of this immigrant rabbi to best serve his community in the new environment he – and they – now occupied.

[1] Yosef Goldman, Hebrew Printing In America, 1735-1926: A History and Annotated Bibliography (Brooklyn, NY: YG Books, 2006), 519.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Annie Polland, Landmark of the Spirit (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 92.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.