Tchiya Froman

Translated by Shaul David Judelman

The Life and Times of R. Menachem Froman: A History of Synthesis

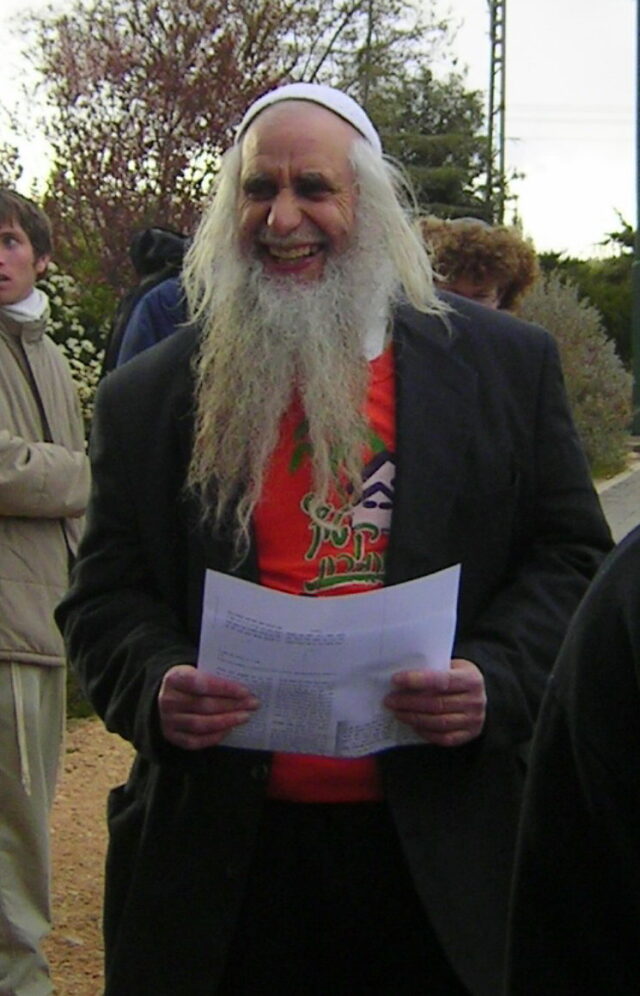

R. Menachem Froman was a figure of contradictions. He was an alumnus of the Reali School in Haifa and a member of the “Young Labor,” a student at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he studied philosophy and Jewish thought, a disciple at Yeshivat Merkaz Ha-Rav in Jerusalem and personal aide (shamash) to R. Tzvi Yehuda Kook, a member of the Gush Emunim settlement movement, and, at the same time, a voice calling both for peace and for Jews to return to the full expanses of the Land of Israel.

In his activism, Froman sought to apply to Israeli politics the fundamental conceptual framework of the Zohar: the general encounter between opposite and contradictory movements within divinity, and particularly between its masculine and feminine elements. From this standpoint, he attempted to create bridges between different groups and positions within Israeli society: between religious and secular, left and right, Arabs and Jews. Froman took the radical step of applying the frameworks and faith of the Zohar to the reality of Israeli politics, and to the Jewish-Arab conflict in the Middle East.

In this article, I aim to show, through analyzing a story written by Froman, his sharp internal critique of the inherently “masculine” nature of the settlement enterprise, and how he sought to fix it by giving greater space to the “feminine” element or the divine feminine, referred to in Kabbalah as the “Shekhinah.” As part of my analysis, I will argue that the literary form in which Froman expressed this critique of the settlement enterprise is no less important than the content of his critique. Although Froman frequently shared this critique in oral lectures and in short opinion pieces published in the Israeli press, his choice to write creative works of literature can be seen as a part of his wider critique of Religious Zionism’s rigid ideologies, and of the ideological stance of Rav Kook’s disciples who led the settlement enterprise and founded the Gush Emunim movement.

Before beginning my analysis, a note is in order about feminism and the terms “masculine” and “feminine” as I use them throughout this article. Without rehashing the history of various feminist movements and their internal divisions and distinctions, we can say simply that some feminist movements have jettisoned the idea of essentially masculine and feminine qualities as, at best, outdated and unhelpful, while others have argued for the importance of maintaining some sense of essentially masculine and feminine qualities. These latter groups have argued that, in rejecting gender essentialism wholesale, we will end up enforcing an even more rigid societal order than before, because society will continue to celebrate masculine qualities and dismiss feminine qualities, but will now lack the language to critique that hierarchical organization. Both the analysis of the article and the thought of Rav Froman analyzed therein work from within a framework of gender-essentialist feminism, seeing equality and liberation as emerging through gender, not despite it.

Choosing the Literary Genre as a Feminist Act

The choice of the literary genre as a medium for conveying critique is a conscious one, engaging with life on an existential rather than merely intellectual level. In Froman’s words, it means choosing the “Tree of Life” rather than the “Tree of Knowledge.”[1] When writing literature—as a genre—the author does not have in mind that they possess and are conveying absolute truth. Literature creates social change by telling its truth with nuance, capturing the full palette of human experience in a developing narrative of emotions, interactions, doubts, and more.

Froman primarily taught Torah orally, but he put his original mystico-political social theory in writing: as essays published in the press, as unpublished plays, as two books of poetry (only one of which was published during his lifetime), and also in literary prose, some of which was published in the press and some of which has since been archived by his family at the National Library of Israel.[2]

Against the backdrop of the choice of the vast majority of R. Tzvi Yehuda Kook’s students to teach and study Torah while composing ideological-theological treatises, Froman’s choice of the literary genre as an additional means of expression constitutes a form of rebellion. We might even interpret it as a decision to forge an alternate path to the elder Rav Kook, avoiding the mediating figure of Rav Tzvi Yehuda, whose interpretations of his father’s thought had become canonical in the Religious Zionist community. Froman sought to connect with a vision of the elder Rav Kook, who wrote that literature is the genre best fit for expressing spirituality.[3] According to Froman, literature is the genre most capable of linking reflective philosophical thought with human experience.

Froman also relates the dichotomy between reflection on life and “life itself” to the binary distinction between Left and Right in Israel. While the Right lives life itself, the Left is more engaged in observing life and analyzing it from an external perspective.[4] Froman wrote about this in an essay titled “For the Sake of Unification,” published in 2008.

Here we come to a central idea that I’ve been walking with for years: In my opinion, the Right is the religious perspective, in the sense of the very relationship between man and God, and the Left is the intellectual world that defines things. That is, if while a person prays, he also defines to himself ‘I am praying,’ then he’s moved to the Left, because he exited the relationship between him and the Holy One, Blessed be He, and is now looking at himself from above. You have a relationship with God, but the moment you define it intellectually, it descends to the world of the Left, to the horizontal axis, to the world of objects—prayer as an entity. On the other hand, there is prayer in its occurrence when it essentially does not belong to the world of entities, it is the movement itself. Entities are the world of the Left, and the relationship is the world of the Right. The Right is divine abundance; in the Right, you flow, but the moment you say ‘I am flowing,’ you’ve already descended to the world of the Left.[5]

On the one hand, literary and theatrical forms of expression provide the opportunity to observe life “from the outside” because they are presented with a certain distance from life itself, reflecting on and conceptualizing life. On the other hand, they maintain a sense of being “internal” to life because the genre evokes the emotional experience of the viewer or reader. Therefore, according to Froman, they are forms of expression capable of creating a bridge between internal experience and external observation. Froman’s choice to write stories, plays, and even poetry was an attempt to invigorate the religious world around him with Rav Kook’s hope for a Judaism that fully engages the human experience, rather than remaining in the theological or ideological realms.

Froman’s second motivation for reclaiming the elder Rav Kook’s call for a literary renaissance is rooted in the latter’s call for the free expression of creativity and the elevation of freedom as a significant religious value. Froman was drawn to Rav Kook’s championing of freedom and argued that freedom is a central value in the life of a religious person:

People can’t accept that the call to freedom can be a religious project. Despite our sages’ statement that “no one is truly free except one who engages in Torah” (Mishnah Avot 6:2), most religious Jews are taught, for the sake of religion, to give up on their freedom… But for me, freedom is the primary aim of religion.[6]

Religion is often identified with obedience and with slavish submission before the power of God. What room is there in such a religion, Froman asks, for free creativity? Rav Kook argued that keeping the Torah is about freedom and authentic self-expression,[7] and Froman connects that to his call for creativity. As a religious value, Froman argues, freedom does not only mean authentic observance of the commandments, but also free, creative expression via the arts in general, and literature specifically.

Froman’s concept of freedom is not about the absolute expression of the “self,” but rather the human attempt to be liberated from it.

Everyone thinks that being free means being “Me.” But in my life experience, the primary chains holding me back are my internal chains. My self-definitions. When I liberate myself from myself, that’s when I am truly free… Getting married—as the all jokes say—is like committing suicide, like going to sleep. Finally being free.[8]

True freedom, Froman says, is not merely freedom from external compulsion or constraints, but freedom from the ego, from your internal self-definitions. Freedom from your own self-conception can be achieved in a variety of ways. One way Rav Froman champions is through engaging with and committing to other people—hence he sees “getting married” as “finally being free.” Another path to this freedom, one he returns to on several occasions, is the creative medium of theater, where a person can disguise themselves as another character and free themselves from themselves.[9] Similarly, in writing literature, the author consciously tries to step into the minds of their characters, which may be very different from their own.

Elevating creative freedom as a theological value shifts the entire constellation of religious hierarchies and constructs. Froman cites Rebbe Nachman’s claim that Judaism in his time had undergone a shift from “beginning” at Passover to “beginning” at Purim and provides his own dramatic gloss:

Rebbe Nachman often stops in the middle of a discussion. However, there is one place where he actually stops right in the middle of a sentence. “For in the beginning, all the beginnings began at Passover, and therefore the mitzvot are all in memory of the exodus from Egypt. But now – ” (Likkutei Moharan II:74). His intent was that, in classical Judaism, all of the commandments commemorate the exodus from Egypt, but now we have reached a new era, an era of laughter and freedom. Until now, all the commandments were very serious. Passover is about pathos. The Torah has lots of pathos, it’s very serious. Now, we have a new era, a new Torah, the Torah of the land of Israel, the Torah of the Messiah. All the commandments commemorate the laughter of Purim, not the pathos of Passover. To be or not to be is a serious, weighty question. However, Shakespeare wrote in the very same play that the whole world is a stage, that everything is a game. Do you hear me asking the most important question there is in life, whether or not to be? This question is just a joke, it’s a game… it’s just a game…[10]

Not only does religion encourage freedom—“no one is truly free except one who engages in Torah”—but religion is itself a kind of play. A person should perform the commandments with the mindset of an actor who knows that, while getting their part right is of the utmost importance within the context of the play, the play itself is just a form of entertainment. The idea that Jewish observance of the commandments is a joke or a game—this Froman identifies as “a new Torah, the Torah of the land of Israel, the Torah of the Messiah.”

Reflecting on the relationship between the Torah and Zionism, Froman makes a similar claim. In the process, he identifies the value of freedom, as expressed in the choice of the medium of literature, as a fundamentally feminine element.

Many years ago, before I began learning Torah, I felt that the Jewish religion needed the redemption of becoming feminine, and that’s why the Zionist project arose.

The Torah of exile is a masculine Torah… The Zionist enterprise brought us to the land. Zionism’s purpose was to make the Jewish religion and the Jewish spirit more feminine, softer. The Torah of the land of Israel is a Torah of peace, not defensiveness and overcoming. This difference manifests in the transition from learning halakhah and laws, which are hard as iron, to learning Zohar, which is soft as light. The goal of alchemy is to turn iron into gold, into light. The alchemy of religion transforms it from obligation into freedom.[11]

This freedom is not simply a personal virtue. Not only the religious individual, but also Judaism itself must undergo a transformation. This is the same transformation to which Rebbe Nachman gestured, only Froman isn’t pointing just to the commandments, but also to Jewish life as a whole—how Jews orient themselves toward the world, each other, and the rest of humanity.

Froman enacts this same transformative shift in choosing to write stories and plays. This writing is a search for freedom, which he sees as both feminine and as the highest religious value. This feminine freedom is a radical freedom, standing opposite the masculine position which claims to discover truth and essence.

Freedom is the opposite of truth, for nothing is more slavishly restrictive than truth, from which you truly cannot escape. The entirety of human history can be seen as one long struggle between truth and freedom. Our era is characterized by rejecting truth and seeking freedom. This revolution is feminist in nature, for truth is masculine, active, and domineering. Freedom, on the other hand, is female. The masculine sefirah of “Hokhmah” [wisdom], the supernal father, is called “Ḥokhmah,” an anagram for the words “koaḥ mah.” It is the power (koaḥ) to ask, “What (mah)?” “What did you say?” “What is the truth?” In contrast, the feminine sefirah of Binah [understanding] asks, “Who?” … From a feminine point of view, who says a thing is more important than the thing that is being said. Existence precedes essence.[12]

Here Froman’s understanding of freedom takes its most radical form as the very opposite of truth. Truth is typically imagined as the correspondence between what a person says and the facts of the world. On this model, the value of a person’s words—to say nothing of their actions or art—is determined by the already existing state of affairs in the world. In contrast, free creativity makes things which bear at most incidental similarity to what already exists. Froman cites the existentialist slogan, “Existence precedes essence,” meaning that who we are and what we choose in life determine the meaning of our lives more than any pre-existing ideas about who we are supposed to be.

This radical, creative feminine freedom is both artistic and political. Froman’s very choice to write his theological-political messages as literary works of fiction was a bold statement about prioritizing the existential realm of life over ideological doctrine. In doing so, he also chose to center creativity and creative expression as the supreme religious value, superseding the classic claim of truth as the exclusive foundation of religion. In both of these steps, Froman sought to create and drive a feminization of religion.

Literary Influences: Rebbe Nachman and the Zohar

Froman’s departure from the path of Rav Kook’s students can also be seen in his adoption of the Zohar and Rebbe Nachman of Bratslav as additional primary sources for his spiritual and political approach. Both of these sources are uniquely literary—in addition to being philosophical-exegetical—in how they convey their spiritual messages. In addition to its analytical sermons, the Zohar often expresses its ideas through stories, and Rebbe Nachman is also known for embedding his novel spiritual ideas within stories. Drawing on these sources of inspiration enabled Froman to forge a different path, one that contains more hybrid spiritual elements, full of movement, humor, and imagination. This is opposed to purely philosophical-ideological writing which seeks to arrive at final, exclusive truth and present a consistent system—a method and goal that Froman perceived as dogmatic and rigid.

Analysis of the Story “Life as an Arrow”

The Historical Background of the Story

The story “Life as an Arrow” was published in the Gush Emunim journal Nekudah in 1986, roughly a year after the trial of the members of the Jewish Underground.[13] The Underground crisis saw core members of Gush Emunim convicted for attempting to blow up the Al-Aqsa Mosque and assassinate Arab community leaders. This event, coming at the tenth anniversary of the Gush Emunim movement and on the heels of the evacuation of the Sinai settlements, forced Gush Emunim to engage in introspection regarding its methods of operation and directly confront fundamental issues such as the relationship between Gush Emunim and the state, and the tension between national unity and the sanctity of the land. Froman’s story, printed in the movement’s journal, can be read as a theological response to these issues.

The story describes the relationship between a man and his wife, the first settlers in a small, early-stage settlement. This couple serves as an allegorical representation through which Froman examines the relationship between the masculine and feminine elements within the settlement enterprise. It is evident that Froman believes that the act of conquering the land and settling, which was the practical end of Gush Emunim’s ideology, stands in opposition to and even harms the marital and intimate dimension. Conquest is a masculine act, which, in its intensity, did not allow the feminine aspect to be expressed and developed.[14]

The Arrow as a Representation of Masculinity

The arrow, a central motif in the story “Life as an Arrow,” is both a symbol of masculinity and a military image that joins together human power, warfare, and sexuality. Putting this image in the story’s title establishes from the outset its central theme: the exploration of masculinity and masculine power within the context of conquering and settling the land. In this context, the arrow represents the continuous, unidirectional effort of a man both to conquer and dominate the land and to realize his identity.

In the Jewish tradition, the arrow is employed as a phallic symbol, combining military strength with the sexual meaning of seed. The Book of Psalms even makes the meaning of seed primary. For example, Psalm 127, which forms the background of Froman’s story, presents the arrow as a metaphor for sons, a man’s offspring and his true “inheritance,” as opposed to the land. The verse emphasizes that a man’s seed, his children, are the arrows leading to his inheritance, not weapons in the classical sense:

3 Lo, children are a heritage of the Lord, the fruit of the womb is a reward. 2 As arrows are in the hand of a mighty man, so are the children of one’s youth. 3 Happy is the man who has his quiver full of them, they shall not be put to shame, when they speak with their enemies in the gate.[15]

In the following chapter, Psalm 128, which describes those who fear God and walk in His ways and bring peace upon Israel, a man’s children are represented by the image of olive saplings planted around his table.

1 … Blessed are those who fear the Lord, who walk in His ways. 2 You shall eat the fruit of your labor. You will be blessed, and it will be well with you. 3 Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine within your house, your children will be like olive shoots around your table. 4 Behold, thus shall the man who fears the Lord be blessed. 5 May the Lord bless you from Zion. May you see the prosperity of Jerusalem all the days of your life. 6 May you see your children’s children. Peace be upon Israel!

The psalm envisions bringing peace to Israel through the image of a healthy, fertile family home. The man is God-fearing, his wife is as a fertile vine, and their children are like olive trees growing around the table.

In our story, this ideal picture never materializes. The couple’s wellbeing and that of their family are flawed from the start, exemplifying a deeper spiritual defect in the settlement movement at large:

How good and pleasant it is to return to a home filled with love in the evening. She wasn’t waiting for him. He peeked in and entered (u-faga) his caravan, wondering and gazing at how this small, humble room could become such a vast and defiant space. Around the unlaid table were several fresh olive-wood chairs. His wife sat at the far end of their home.

“Hello,” he said faintly, but she couldn’t respond. He shut his eyes to block out the bad. He needed to do some soul-searching. Repentance. Regret for the past. But he hadn’t merited it. The sons of Gad and the sons of Reuben once went out armed, each with his sword girded at his side. But he? He feared the nights. His wife wouldn’t come to greet him with song and dance.

He thought their journey to the new settlement would bring salvation. Like a tightrope walker, he’d led her after him into an unyielding land. But the rope had reached the wall. The fire of the founders licked at straw, and now they both burned, the fire consuming them together. He opened his eyes and saw the cracks in the bare walls of his caravan. Perhaps it could still be repaired?[16]

While the man returns home and even expects to find a house filled with love, his wife isn’t waiting for him or even to speak to him, let alone coming out to greet him. And this is because he desecrated his piece of Eden, the shared space between him and her. The phrase “He peeked in and entered” (heitzitz u-faga) is borrowed from the famous Talmudic story (Hagigah 14b) where four Jewish sages entered the pardes [orchard]—the Garden of Eden, or some other exalted realm of consciousness. In the story, three of them don’t return in peace, and one of those three, Ben Zoma, “peeks and is wounded” (heitzitz ve-nifga). In our story, the word “is wounded” is exchanged with “he wounds.” This means that the wounding is his, and that it is an active wounding, a toxic masculinity that expresses itself in acts of settlement and conquest. The active harming happens in the realm of partnership, within the home itself.

The passage ends: “The fire of the founders licked at straw, and now they both burned, the fire consuming them together. He opened his eyes and saw the cracks in the bare walls of his caravan. Perhaps it could still be repaired?” Here, too, the story alludes to a rabbinic text, this time to a famous teaching of R. Akiva, the only sage to safely enter and exit the pardes: “R. Akiva taught: man and woman – if they merit, the Divine Presence rests between them. If they do not merit – they are consumed by fire” (Sotah 17a). From the overwhelming ideological flames of the settlement movement’s founders, the Divine Presence left the home and the marriage, and all that remained was a consuming fire. The marriage in Froman’s story bears no fruit: The table is not set, and instead of the children, the table is surrounded only by empty olive wood chairs. The promises of Psalm 128 do not come to fruition in this home—neither “your wife is like a fertile vine” nor “your children are like olive saplings around your table.”

From the very beginning of the story, Froman is sharply asking the questions that interest him: How can one settle the land? To where does the settlement movement lead? What price does it exact? And how can it be redeemed from itself?

The metaphor of the arrow also appears in Jewish tradition as a symbol of wasted seed, or seed that never bore fruit. For example, the sages in the Jerusalem Talmud interpret a verse from Jacob’s blessing to Joseph: “But his bow abode firm, and the arms of his hands were made supple, by the hands of the Mighty One of Jacob, from there is the Shepherd, the Stone of Israel” (Genesis 49:24), connecting it to the story of Joseph resisting Potiphar’s wife and overcoming his urge to lie with her.

It is written: “But his bow abode firm.” R. Shmuel bar Nachman said: His bow was stretched and then returned; R. Abun said: His seed was scattered and came out from his fingernails, as it is said, “and the arms of his hands were made supple” (y. Horayot 2:5).[17]

The sages saw the release of Joseph’s seed through his fingertips—rather than through a physical union with a woman—as an act of restraint, demonstrating his moral rather than physical strength. Yet in our story, this act is re-interpreted as a waste of seed and an inability to connect with the woman:

He looks once again at his hands. His ten long fingers are like hollow pipes of influence: they sowed across all fields and scattered to all directions. Could this hand possibly open like that of a beggar seeking kindness?

The critique of the man, representing the founders of the settlement movement, intensifies. The land becomes a destructive substitute for the woman—the seed does not reach its proper destination and instead falls to waste, simultaneously corrupting the man’s own soul. The man’s sin in our story is that he chooses only one movement—the outward, masculine force directed toward the land—without coming into contact with the feminine, receptive movement represented by his wife.

The possibility of change and repair in this story is presented here as a question: “Could this hand possibly open like that of a beggar seeking kindness?” Could the movement of occupation and settlement, represented here by the hands that have worked both the land and the winds, endure a transformation from a limb of action and impact (masculine) to open (and thus feminine) hands of receptivity?[18]

The Motif of the Arrow in Rebbe Nachman’s Story of the Seven Beggars

The contrast between the motifs of the active arrow and the receiving hand is built on a reference to Rebbe Nachman’s “Story of the Seven Beggars” (Sippurei Ma’asiyot 13). In the middle of the tale, one of the figures tells of an attempt to save a princess, or, as interpreted by Froman, the feminine foundation of reality. In Froman’s story, the protagonist tries to repair the damage to his marriage and suggests to his wife that they read together from Rebbe Nachman’s stories. He opens with the chapter of the sixth beggar,who claimed that he had no hands precisely because he had tremendous strength in his hands but used them for something else. Within the framework of “Story of the Seven Beggars,” arrows receive a place of prominence when the sixth beggar takes the stage, and Froman’s protagonist immediately applies the tale to his own life:

“One [beggar] boasted that he had such strength and power in his hands that when he shot an arrow, he could pull it back towards him.” He paused and listened closely: Above them hovered the question: Could he retrieve the arrows he had shot at her throughout his years of activity? And the sound of her wounded wings, struggling to hold her weight, was heard in the air.

The protagonist realizes as he reads that true strength is measured in the ability to retrieve the arrows—in other words, the ability to recover from masculine power. In simpler terms, by limiting the force and ideology inherent in the settlement activity, he would metaphorically retrieve the arrows that he had shot at his wife during his years of ideological activism. The story depicts his wife as a bird flying through the air, with wounded wings and nowhere to rest—reminiscent, of course, of the biblical flood and Noah’s sending of the dove to see if the waters had receded and if it could find rest on the land. This suggests that, at the exact time that the protagonist sought to inherit and possess the land, he actually drove his wife away. The image of the wounded bird with no place to rest also alludes to the Tikkunei Zohar’s portrayal of the Shekhinah as a bird, which persists in an exiled and desolate state, flying without the ability to rest on land.[19]

The man in the story understands that he must begin a process of repair within the home and seeks to study Rebbe Nachman’s text with his wife as an act of healing. The lines between Rebbe Nachman’s story and Froman’s protagonist blend as the latter searches desperately for a way out of his personal-political crisis.

He thought again and whispered: “He can still return [the arrow].” He who knows to despise or fear retreat—does he also know how to return? “But what kind of arrow can he return, etc.” He replied: “A certain type of arrow he can return.” I said to him: “If so, you cannot heal the princess since you cannot return or draw back any arrow but a certain type. Therefore, you cannot heal the princess.” His voice fell. He knew: she was beyond repair. From every type of arrow, she was wounded. Too many nights she waited for him while he planted caravans on every high hill. Too many times he was not with her. His existence was amidst the checkpoints, the crowds, the excitement of activism. The friction with history. In essence, all the arrows he had shot at her were of one type. As a man of valor. To scatter the arrows away from him and move on. To ascend. To climb. To conquer the mountain. For years he had shot his life outwards, life as an arrow.

The man faces an impasse. First, the movement of retreat is the greatest enemy of the settlement movement. He asks himself whether he, for whom retreat is the greatest existential threat to his life’s work, can take up this movement of retreat in his personal life. Second, he realizes that his wife is already too hurt by him. The masculine force of the settlement movement has succeeded in harming the woman—representing the Shekhinah—and she hovers in the air, wounded, with no place to rest her feet.

Continuing to read Rebbe Nachman’s story, the man discovers the solution:

“‘I asked him what wisdom can you put in your hands? For there are ten measures of wisdom.’ He replied, ‘A certain wisdom.’ ‘If so, you cannot heal the princess because you cannot know her pulse, as you can only discern one pulse, and there are ten types of pulses, and you cannot know more than one pulse because you cannot place in your hands more than one wisdom.’”

Here his heart stood still. This is the wisdom—to feel the pulse. Many times he had taught his wife as now, but he had never seen the wisdom as clear as in this moment. Like a meteor, it came down from the heavens and crushed him: To give wisdom is to feel the pulse.

He suddenly understands that the repentance and repair he needs cannot be accomplished by his hands or his male organ, but only by his heart. The person who can heal the princess must possess the wisdom of the pulse. He must listen to the heart and hear the pulse of reality. In other words, to heal and repair the feminine aspect of reality, he can no longer impose his opinions and actions on reality but must listen to reality itself and the pulse of life within it. However, as the story goes on, his study of Nachman’s tale casts a shadow on the solution he has found—his realization may have come too late.

“‘For there is a story that once a king desired a princess and endeavored with tricks to capture her, but the king did not know what to do to her. Meanwhile, her love for him became corrupted little by little, and each time it became more and more corrupted.’ … Like Amnon and Tamar, he managed to think, under the tumbling words. ‘So she too lost her love for him more and more each time. She hated him and fled from him…’”

The text sealed his fate. Pain froze his body. His bones dried up. His hope was lost. He was condemned. With difficulty, he looked directly at her—to see his wife fleeing from his house. His eyes met hers, on the edge of the two abysses before him, she stopped. Abyss called unto abyss. The sound of the waves and breakers they had crossed. The arrow that would not return crossed them both. His hands groped with no handhold to be held. Forward and backward at once. The beating of his heart seemed to echo in the air and fill the room.

In this description, there appears to be no way back: The man cannot repent, the damage has already been done and cannot be healed. The man tries with all his might to cling to the actions he knows: He begins to share with her the events of his day and every feverish statement he spoke on television, casting his words at her one after the other. But the imagery of these words is no longer like arrows but rather like rings, which join together to form a choke-chain around his neck. He suddenly views the day’s events from an external, reflective point of view, and the scene in which he spoke with such fervor appears to him like a scene from a horror play, as he suddenly becomes aware of being trapped within the male paradigm:

As if possessed, he began to confess to her. The drowning man grasped at a straw and spun with it in a whirlpool, beginning to tell her what he had done today. As he repeated the events to her, ring joined ring, and the heavy chain closed around his neck. He had no more defense. He saw his day’s work as if it were a terrifying play. Everything culminated in his appearance today on television. Finally, he was given the opportunity to explain to the Israeli people the decision of the Council. In the fire of enthusiasm, he shot arguments that could not be answered, straight to the heart of the defeatist public opinion. He gave and gave again irrefutable proofs that there was no way—no way at all—to accept its state of mind. In the closed studio, there is no way to feel the pulse of the listeners, but he was sure that public opinion could only follow him.

At this point, when masculinity overflows its banks and tries to justify itself through self-inflating words, he suddenly experiences a complete fall into the abyss and a sense of returning to his source, recognizable by its circular imagery. These images began with rings joining into a choking chain and continued into the image of an egg.

Into the abyss, he fell, down, down, for the promised land seemed to flee beneath him. He sank rapidly, and in great terror, a deep darkness descended after him like a vulture.[20] Then he raised his hands—he knew there was nothing left to hold on to. He who does not know how to give, take, and feel has no hands. He threw them away from himself and withdrew into himself. Not only did his hands disappear, but also his legs, and the rest of his limbs; everything seemed to contract towards the navel. All the branches returned to their root. During the fall, his body turned into a rounded egg that kept shrinking until it was the size of a grain of earth. His thought encompassed the point, he gave up everything, tore all his perceptions and all his feelings, and they flew around him.

The surrender of the many limbs and the return through the navel to the point of origin allows him a kind of death and rebirth. This process is elucidated by the employment of circular imagery: navel, rounded egg, grain of earth, point. The transition from linear phallic imagery, such as arrows, to circular imagery is critical to understanding the transformation the protagonist undergoes—from the masculine to the feminine.

Connecting to the Feminine Element of Reality – Circumcision in the Zohar

Given Froman’s deep and persistent engagement with the Zohar, it is unsurprising that his story resonates deeply with the Zohar’s understanding of gender—both in its essentialism, and in the way it sees gender relations as underlying the very stability of reality itself. The Zohar’s understanding of the relationship between the masculine and the feminine, and particularly this relationship’s connection with circumcision, provides the backdrop for the resolution of “Life as an Arrow.” After the protagonist’s dramatic fall,

He saw a fire passing between the pieces.[21] This was the sign of the covenant (ot-berit). The hovering over the water ceased, and, from the chaos, a new land was created…[22]

The ot-berit, the sign of the covenant, is a classic Zoharic term for circumcision. As Froman interprets the Zohar, “circumcision” is an expansive mystical symbol, referring not just to the physical cutting of the male’s flesh, but also to the joining of the masculine and feminine divine powers through stamping the feminine upon the masculine. The Zohar understands circumcision (berit milah) to be a world-founding act, similar to the covenant (berit) that constitutes and maintains the relationship between a husband and wife.

Come and see: When the blessed Holy One created the world, it was created only through Covenant, as is said: Bereshit, In the beginning, God created (Genesis 1:1)—namely, berit, covenant, for through Covenant the blessed Holy One erected and sustains the world, as is written: Were it not for My covenant day and night, I would not have established the laws of heaven and earth (Jeremiah 33:25). For Covenant is the nexus of day and night, inseparable.

Rabbi El’azar said, “When the blessed Holy One created the world, it was on condition: ‘When Israel appears, if they accept Torah, fine; if not, I will reduce you back to chaos. The world was not firmly established until Israel stood at Mount Sinai and accepted Torah; then the world stood firm. Ever since that day, the blessed Holy One has been creating worlds. What are they? Human couplings, for since then the blessed Holy One has been matchmaking, proclaiming: ‘The daughter of so-and-so for so-and-so!’ These are the worlds He creates.[23]

The Zohar here makes a radical claim: Without the covenant, the world could revert to chaos and void. This passage describes the covenant as the connection between day and night, between the people of Israel and their God, as well as the bond between the masculine and feminine. Indeed, the man in our story experiences the breach of the covenant between him and his wife as a return to a state of chaos: “Into the abyss, he fell, down, down, for the promised land seemed to flee beneath him.” The land represents the woman, fleeing from him, leaving him plunged into the abyss. As his toxic, conquering masculinity has destroyed his relationship with his wife, so too the relationship between Gush Emunim and the land.

Another Zoharic passage discussing Abraham’s circumcision presents a homiletic reading of the verse, “And your people are all righteous; they shall inherit the land forever” (Isaiah 60:21). The homily asks why the verse claims that all of Israel is righteous, given that there are wicked individuals within the people who violate the laws of the Torah. The Zohar answers that the righteousness it speaks of is connected to the act of circumcision as a union of the masculine (the sefirah of Yesod and the male organ) and the feminine (the sefirah of Malkhut).

This Zoharic homily directly raises the key theopolitical question which underlies Froman’s short story: Who are the righteous that can inherit the land? What is the act of righteousness that enables a person to inherit the land? The Zohar answers:

But so it has been taught in the mystery of our Mishnah: Happy are Israel who bring a favorable offering to the blessed Holy One, offering up their sons on the eighth day. When they are circumcised, they enter this fine share of the blessed Holy One, as is written: The righteous one is the foundation of the world (Proverbs 10:25). Having entered this share of the Righteous One, they are called righteous—truly, all of them righteous! So, they will inherit the land forever, as is written: Open for me gates of righteousness…. through which the righteous will enter (Psalms 118:19–20). Those who have been circumcised are called righteous. …

The righteous will inherit the land (ibid. 37:29). They will inherit the land le-olam, forever. What does le-olam mean? As we have established in our Mishnah. This word has already been discussed among the Companions. It has been taught: What prompted Scripture not to call him Abraham until now? So we have established: Until now, he was not circumcised; once he was, he entered this ה (he), and Shekhinah inhered in him. Then he was called Avraham, Abraham, corresponding with what is written: These are the generations of heaven and earth be-hibbare’am, when they were created (Genesis 2:4)—it has been taught: be-he bera’am, With a ה He created them; and it has also been taught: be-Avraham, through Abraham.”[24]

In other words, the act of circumcision marks a person with the seal of the “righteous,” represented by the sefirah of Yesod. According to the Zohar, the term “land” signifies the sefirah of Malkhut, that is, the divine reality also known as the Shekhinah. Therefore, circumcision, the ability to create a covenant through “offering up”—as opposed to conquest and domination—joins the masculine element, Yesod, to the feminine element, Malkhut, which is the Shekhinah, and thereby leads to inheriting the land.

The seal in the flesh enables a person to come into contact with the feminine element, referred to as “land.” The seal itself is a circular cut around the phallus. Only after Abraham was circumcised could the Shekhinah dwell within him—as represented by the letter ה added to his name. From the moment the feminine element was sealed in Abraham’s flesh, he became able to inherit the land, meaning he could establish a connection and a sense of belonging with the land, which to the Zohar is nothing other than the Shekhinah.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have analyzed R. Menachem Froman’s short story, “Life as an Arrow.” Framing the story with his understanding of literary writing as a feminine act, I located Froman’s writing of stories, poems, and plays within his broader concerns to elevate the feminine, and his sense that Judaism itself needs a feminine revolution. Zionism, he says, was supposed to be one such feminine revolution. “Life as an Arrow” makes it clear that Gush Emunim and the settlement movement—and perhaps Religious Zionism as a whole—have not created the feminist revolution for which he hoped. Instead, they have become a masculinist ideological project of territorial domination—in need of their own feminist revolution. Thus “Life as an Arrow” ends with its protagonist abandoning his masculinist projects in a desperate—if doomed—attempt to restore his relationship with his wife, to reintroduce an element of covenant (berit) into his life. For as the Zohar teaches, the land is inherited not through conquest but through covenant—not through the masculine qualities of domination and power but through the feminine qualities of openness, receptivity, and faith:

His broken, war-making hands melted away. In essence, he had no hands at all. Yet he was not an amputee (ba’al-mum)—his hands were steady (emunah), outspread in prayer.[25]

[1] “For the Sake of Unification: Societal Engagement as Linking Heaven and Earth” [Heb.], in On the Economy and Sustenance: Judaism, Society, and Economy [Heb.], eds. Aharon Ariel Lavi and Itamar Brenner (Reuven Mass, 2008), 355–379, at 374–375. Available in English.

[2] For an analysis of one of Rav Froman’s unpublished stories preserved in the NLI archive, see Tchiya Froman, “For the Sake of Unification: The Dialectic Between the Ayin and the Yeish in the Thought of Rav Froman” [Heb.], in The Philosophy of Talking Peace (Siach Shalom): Kabbalah, Halacha and Antipolitics, ed. Avinoam Rosenak (Carmel Books, 2024).

[3] R. Abraham Isaac Kook, Ma’amarei Ha-Ra’ayah 9, 53-54; idem, Orot Ha-Teshuvah 17:5. Cf. Moshe Tzuriel, “Literature and the Value of Writing.”

[4] This is related to Froman’s primitivism, a motif which appears throughout his writings. See, for example, R. Menachem Froman, Ten Li Zeman (Maggid Books, 2017), 132, 140–141.

[5] “For the Sake of Unification – Societal Engagement as Linking Heaven and Earth,” 366. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are by Shaul David Judelman. For more on this essay, see Tchiya Froman, “Beyond Monotheism.”

[6] R. Menachem Froman, Hasidim Tzohakim Mi-Zeh (Dabri Shir, 2014), §2. Translations of Hasidim Tzohakim Mi-Zeh by Levi Morrow and Ben Greenfield.

[7] It would be impossible to cite every source in Rav Kook’s writings on this, and the secondary literature is voluminous. For one source, see Orot ha-Kodesh III:97-98.

[8] Hasidim Tzohakim Mi-Zeh, §3.

[9] Cf. R. Menachem Froman, Kof Aharei Elohim (Hay Shalom, 2017), 20.

[10] Hasidim Tzohakim Mizeh, §28.

[11] Ibid., §102.

[12] Ibid., §114. The Kabbalistic themes of this piece draw on Zohar I:1b.

[13] Nekudah 89 (Adar I 5746/February 1986), 16–17. Froman’s language is rife with references to traditional texts, only some of which can be explicated here.

[14] Cf. Hasidim Tzohakim Mizeh, §133: “Settling the land can be an expression of love for the soil and commitment to it, but it can also be a crushing, aggressive act of conquest… It’s not always easy to distinguish between loving the land and strangling it.”

[15] Tanakh translations adapted from JPS 1917.

[16] Unless otherwise noted, all uncited quotations are from “Life as an Arrow.” Translations by Shaul David Judelman.

[17] And cf. Sotah 36b: “‘And the arms of his hands were made supple,’ meaning that he dug his hands into the ground and his semen was emitted between his fingernails” (Koren Steinsaltz translation).

[18] Cf. Hasidim Tsohakim Mizeh, §2: “The settlements are the fingers of a hand extended out in peace, safeguarding peace.”

[19] Tikkunei Zohar, Introduction, 1b.

[20] Cf. Genesis 15:11.

[21] Froman continues to reference Genesis 15, here 15:17.

[22] This section of “Life as an Arrow” translated by Levi Morrow.

[23] Zohar I 89a. Zohar translation from the Pritzker edition by Daniel Matt.

[24] Zohar I 93a. Matt translation.

[25] This section of “Life as an Arrow” translated by Levi Morrow.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.