Emmanuel Bloch

Ed. Note: We previously ran a review of Reclaiming Dignity, which you can find here. The present essay uses the book as a launching pad to consider broader trends in contemporary Orthodox discourse and sociological norms.

Introduction

The contemporary emphasis on tzeniut in Orthodox Judaism is utterly unprecedented.

For most of Jewish history, modesty was not a significant medium of Jewish religious expression. Before the 1960s, female clothing was not conceived as a topic of legal discussion.[1] Compare that with today, when tzeniut is understood, in many Orthodox circles, as a pivotal religious duty, a form of feminine achievement, and a path toward self-fulfillment. This constitutes a fundamental revolution of values within a society that sanctifies conservatism.

My forthcoming book examines how a vague socioreligious norm ascended to the top of the pyramid of Jewish observance. I contend that the issues at stake in tzeniut are foundational for understanding the soul of contemporary Jewish Orthodoxy―a point I will illustrate here by examining the most recent publication in the field.

Reclaiming Dignity: Anatomy of a Success

A new book is taking the Orthodox world by storm: Reclaiming Dignity: A Guide to Tzniut for Men and Women. The book, edited by Mrs. Bracha Poliakoff, includes over 20 essays by overwhelmingly female educators and a halakhic exposition of the laws of tzeniut by Rabbi Anthony Manning.

In the short time since it has been available for purchase, the volume has been acclaimed by readers as a watershed moment. The 1,800 copies of the first edition quickly sold out. Commenting on the Cross-Currents blog, R. Yitzchok Adlerstein emphatically declared Reclaiming Dignity to be a game changer―nothing less than “The Book You Have Been Waiting For.” He is hardly alone to find in the new publication occasion to celebrate. But what accounts for such verbal hyperbole from usually sober rabbinic figures?

Having read and analyzed several dozen rabbinic works on tzeniut, I can venture some explanations to account for the rhapsodic response to the book launch. In my view, Reclaiming Dignity captures a special moment in the social and religious trajectory of the English-speaking Orthodox world. Here is a book that (1) offers a radically new synthesis of the concept of tzeniut, now fused with twenty-first-century ethics; (2) instantiates a new “Orthodox alliance” that rejects religious extremism, internalizes key feminist values, and is more inclusivist; and (3), above all, seeks to relegate to oblivion the previous standard-bearer of traditional Jewish modesty.

Dignity: Not Your Grandparents’ Hashkafah

One concept is so central to the book’s approach that it provides the title of the book: tzeniut as an expression of human dignity. “Dignity” is certainly highly relatable, and R. Manning is hardly the first author to identify it as a core Jewish value―even in the context of modesty.[2] But does “dignity” hark back to the Torah, the Midrash, or the Talmud?

Not really. This concept is modern and secular. According to Charles Taylor,[3] the contemporary notion of dignity must be distinguished from the premodern value of honor. “Honor” is possessed by only the elite; for instance, one is honored with the Légion d’honneur in France or recognized as a duke in the United Kingdom. If everyone is distinguished, it is no longer an honor.

“Dignity,” however, is used in a universalist, egalitarian sense. In this spirit, the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) asserts the “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family.” The idea here is that this dignity is shared by everyone.

Another critical point made by Taylor is that the universality of dignity was intensified, toward the end of the eighteenth century, by the development of an understanding of identity that emphasized authenticity. “Authenticity” implies connecting with something that is not God (per the Torah) or the Good (Plato) but rather our own selves that lie deep within (Rousseau, Herder).

Thus, the contemporary idea of universal dignity implies that recognition is to be accorded to everyone irrespective of wealth, birth, position, achievements, etc. This is given credence by an ideal of authenticity that insists on the moral worth of every person insofar as they are their own selves, irrespective of external factors.

Classical Jewish sources ignore such a resolutely modern understanding of “dignity.” However, Judaism does know of “kavod,” a concept that comes very close to the premodern idea of “honor.” Kavod belongs first and foremost to God―it would be absurd to suggest that the divinity is invested with dignity.

Special individuals also possess a degree of kavod on account of their personal achievements, social positions, or births.[4] Consider: the rabbinic dictum “kol kevudah bat melekh penimah,” a central tenet in modesty education, can be translated as “the honor of a [Jewish woman, who is a] princess, is to remain inside.” Jewish women are designated as nobility. Dignity has nothing to do with it, and, indeed, the implication is that lesser women can be outside. When the sages want to universalize the concept of kavod, they do not resort to tzeniut. Instead, they create an expression that is subversively oxymoronic―kevod ha-beriyyot, the “honor of all creatures.”[5]

The idea of tzelem Elokim was never understood (at least, until recently) as a form of universal dignity. It may be shocking that one medieval commentator (Abravanel) advanced the thesis that only men, and not women, were created in the image of God. He was, to the best of my knowledge, a lone voice in this respect. But the other classical mefarshim also gave explanations that have little to do with the concept of dignity.[6]

Hence, to equate tzeniut with dignity is to achieve a modernist reinterpretation.

Internality and Authenticity

Beyond dignity, certain concepts return with striking regularity in the essays included in Reclaiming Dignity. These include, among others, the ideas of internality and authenticity. For instance:

Internality: “…We are, at our core, deep, spiritual beings. The middah of tznius brings us back to our true depth. When we focus on who we are as a person… we develop our inner world.”[7]

Authenticity: “Let’s recalibrate our moral compasses. Let’s repair and renew the feeling in our spiritual nerve endings. Let’s reinstate the very trait that makes us proud descendants of Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaakov.”[8] To quote a contemporary thinker, “the idea that some things are in some real sense really you, or express what you are, and others aren’t” is the essence of the modern concept of authenticity.[9]

Rabbi Manning sums up the argument eloquently: “Tzniut is therefore presented as a global vision for authenticity, an appreciation of the holiness of privacy, a clarion call against materialism, and a guide to personal wisdom, consideration, and awareness.”[10]

Again, the value of authenticity, the ethics of self-expression and self-empowerment, and the emphasis on interpersonal relations are hardly timeless Jewish values. These are modern, Western values that speak to us because we inhabit a modern, westernized universe―not because they perpetuate a pristine moral message handed down to us from the distant past.

The Demise of the Next World

On the flipside, certain classical Jewish concepts are largely absent, such as the soul, sin, and divine retribution. In Reclaiming Dignity, as in real life, one waits in vain for the messiah to appear.

Perhaps more surprising, to an extent, even God has gone AWOL. As Mrs. Elisheva Kaminetsky correctly diagnoses in her essay, “We are not always comfortable speaking about Hashem.”[11] This is of course ironic. While Kaminetsky seeks to reconnect tzeniut with “God Talk,” the overall thrust of the book reflects precisely that which she deplores. While some of the erstwhile fundamentals of Jewish life are occasionally mentioned in passing, the heart of the action lies elsewhere. Mrs. Ilana Cowland tellingly observes in her essay that “God has nothing to gain from our mitzvah observance… It is legitimate to begin by asking, ‘How does this particular directive benefit me?’”[12] This interrogation makes good sense in a world where tzeniut is a way for people to connect to their true inner selves.

To borrow Max Weber’s terminology in Economy and Society, Orthodox Judaism has largely become an inner-worldly religion. The focus of religious behavior is on activities that lead to results in the context of the everyday world. The next world (olam ha-ba), and its constellation of related extra-worldly ideas has not entirely disappeared, but it certainly has receded in the background.[13]

Dynamics of Continuity and Change

Modernity and tradition are tightly interwoven in Reclaiming Dignity. On the one hand, the book asserts implicitly that Torah values are eternal and radically ahead of their time; on the other hand, it often expresses ideas that are influenced by, if not directly borrowed from, modern secular culture.

Such large-scale reinterpretations function a bit like a Procrustean bed. Some sources are extended almost beyond recognition, like the idea of dat yehudit. For 18 centuries, halakhic sources have confined it to divorce law and applied it exclusively to women.[14] In the long history of Jewish law, R. Manning is, to the best of my knowledge, the first to expand dat yehudit to also encompass men and the first to apply it to many areas of human activity (cycling, possibly driving a car, etc.). This helps him justify the legitimacy of a wide range of communal practices.[15]

Unpopular sources, on the other hand, fall entirely by the wayside. Think, for instance, of the Talmudic passage that affirms that hair-covering is one the “ten curses” inflicted upon all of Eve’s female descendants and presents the married woman as “wrapped like a mourner” and “incarcerated within the prison” of her home.[16] Other texts also get the silent treatment. A full analysis of Reclaiming Dignity’s hermeneutics would necessitate a separate essay.

One useful concept is “coalescence,” an expression coined by sociologist Sylvia Barack Fishman to describe the harmonization of tradition and modernity. According to Fishman, many American Jews, even among the very Orthodox, have lost all awareness of differences between Jewish and American values:

During the process of coalescence… the “texts” of two cultures, American and Jewish, are accessed simultaneously… These values coalesce or merge, and the resulting merged messages or texts are perceived not as being American and Jewish values side by side, but as being a unified text, which is identified as authoritative Judaism… Many American Jews―including some who are very knowledgeable and actively involved in Jewish life―no longer separate or are even conscious of the separation between the origins of these two texts.[17]

Thus, the power of Reclaiming Dignity’s ideas does not lie in its wholesale rereading of traditional concepts through a contemporary conceptual matrix. That is not what the book seeks to do. Instead, it offers a more complex melding of traditional ideas with new ones, creating a new conceptual synthesis that speaks to many contemporary readers.

Reclaiming Dignity, then, advances a philosophy of tzeniut that is historically contingent. It coalesces traditional sources and attitudes about Jewish modesty, a modern understanding of universal dignity, and even more recent values such as self-actualization. The book’s success is due, in part at least, to its ability to capture the views of a religious community (Anglo-Orthodox Jewry) that is much more acculturated than its religious leaders care to admit.

A Veiled Enemy

This makeover of tzeniut is not taking place in an ideological vacuum. Undercover, Reclaiming Dignity is engaged in a fierce battle. Its hidden archenemy is the famous (or infamous) volume authored by R. Pesach Eliyahu Falk, Oz ve-Hadar Levushah. That book was also distributed by Feldheim, but 25 years earlier―in a different era on the modesty timeline.

R. Falk (1944-2020) was a well known posek (halakhic decisor) in Gateshead (UK). It is no exaggeration to state that his work represented, at the time of its publication in 1998, a watershed event in the English-speaking Haredi world. It became an instant classic about the newly invented laws of tzeniut. Further publications―in 2010, of a summary booklet embellished with educational “diagrams”; in 2011, of a two-volume edition for daily learning;[18] and the mushrooming of home-study groups[19]―all attest to its continuing impact and popularity over the years. In an obituary published in 2020, Ami Magazine reported that some 65,000 copies sold during Falk’s lifetime. For nearly three decades, R. Falk’s vision of tzeniut has reigned nearly uncontested in the Anglo-Haredi camp.

For R. Falk, tzeniut is more important than any other mitzvah traditionally associated with women. Moreover, modesty is the female equivalent of learning Torah for males: a commandment that is almost infinite in the demands placed on its practitioners, is applicable at all times, and represents a religious woman’s own way of connecting to the divine.

Torah learning and tznius are both the central axis upon which one’s life turns. Their presence gives forth life, whilst their absence spells destruction.[20]

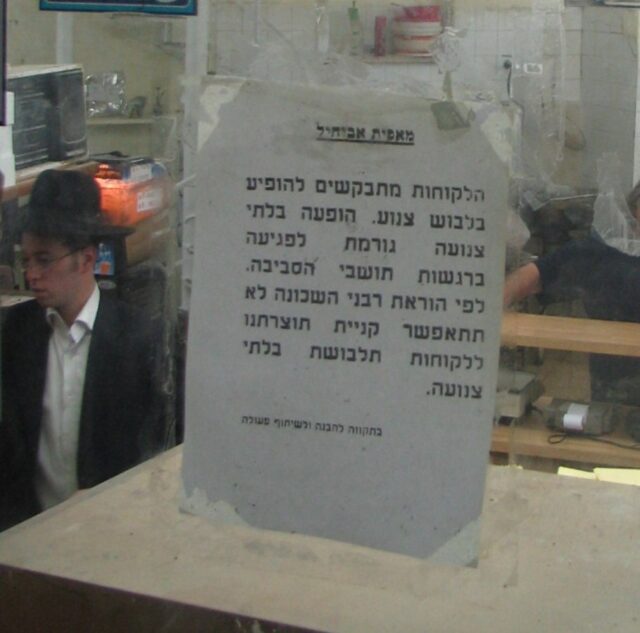

Oz ve-Hadar Levushah is an extremely comprehensive book that is literally obsessed with details. It has been a major catalyst for strong and complicated feelings, sometimes even significant trauma, experienced by many young women who were inculcated the “laws of tzeniut” in Orthodox institutional settings. Critics have denounced its tendency to standardize tzeniut and dismiss local customs, its excessive stringency and fanaticism, and its mingling of ideological consideration in legal matters.

Oz ve-Hadar Levushah is the elephant in the room. When R. Manning completely omits the most popular book from the list of recommended resources about tzeniut, it is no oversight;[21] when he mentions Oz ve-Hadar Levushah in the footnotes exclusively only to always reject its positions, it cannot be a coincidence.[22] The only possible explanation is that R. Manning is trying to cancel Falk’s extreme vision with a more moderate approach. Stated differently, Reclaiming Dignity is changing the conversation on tzeniut by attempting to render Oz ve-Hadar Levushah irrelevant. So far, it is succeeding remarkably well at this task.

Anglo-Orthodoxy: Between Israel and America

For a volume targeting an English-speaking audience, a surprising number of Reclaiming Dignity’s writers (roughly half) currently live in Israel.[23] In comparison, it is estimated that less than 200,000 American Jewish citizens live in the Holy Land.[24] Ergo, English-speaking residents in Israel are disproportionately represented in the book.

There is an archetypal demographic pattern at play here: certain highly idealistic Anglo Jews, looking for a more spiritual and less materialistic lifestyle, make aliyah. They populate settlements in the Gush Etzion (Efrat, Neve Daniel, Alon Shvut, Elazar, etc.) and specific neighborhoods in Jerusalem (Har Nof, Rehavia, Baka, etc.). They study Torah, sincerely and devoutly, in institutions of higher education that cater specifically to the spiritual needs of olim hadashim (new immigrants). Time passes. A few years down the road, some of them reintroduce themselves as teachers and mentors to their home communities in the diaspora.

There is much to admire in this story. But regardless of the number of decades spent learning in Israel, an Anglo immigrant rarely sees the world in the same way as a “sabra.”

Tzeniut is the perfect inkblot test. My research shows that modesty is conceptualized differently in various religious communities. Since the 1960s, several visions of tzeniut have emerged, each encoding a different conversation on the place of law, sexuality and the body, relationships between men and women, and Jewish exceptionalism.

Israeli discourses of tzeniut revolve around the idea of collectivity. Rabbi Shlomo Aviner, for instance, perceives tzeniut as a prerequisite for Jewish peoplehood.[25] For Rabbis David Stav and Avraham Stav, modesty establishes healthy boundaries that are necessary for any community to flourish.[26]

Diasporic discourses, on the other hand, tend to center on the individual. Thus, for R. Yitzhak Eizik Rosenbaum, tzeniut preserves the individual Orthodox man from impure thoughts,[27] and for R. Pesach Eliyahu Falk, modesty expresses the inner nobility of the individual Orthodox woman.[28]

This divide is easy enough to explain. In Israel, questions of religion and state (dat u-medinah) are burning public affairs, while in the diaspora this public dimension is absent (France) or much more subdued (USA, UK). From this standpoint, Reclaiming Dignity, with its emphasis on personal authenticity and self-actualization, represents a vision of tzeniut that is situated―“made in Israel,” but clearly not Israeli. Reclaiming Dignity is a book written by Anglos overseas for Anglos in their homeland.

Builders of Internal Bridges: The New Kiruv

Another demographic is overrepresented in Reclaiming Dignity: kiruv (outreach) professionals. Again, as far as I can ascertain, this is true of many authors published in the first part of the book[29] and of R. Anthony Manning himself. As to R. Yitzchak Berkovits, not only is he Rosh Yeshivah at Aish HaTorah, but he is also considered to be the unofficial posek of the kiruv world.

The kiruv world has been in severe crisis for a decade and a half. Recognized superstars, like R. Akiva Tatz and R. Dovid Gottlieb, are not growing any younger, and one would be hard-pressed to find comparable heavyweights in the younger generation. Testimonies of returnees, like R. Mayer Schiller’s The Road Back: A Discovery of Judaism, are almost unheard of in this epoch. My own religious alma mater, Ohr Somayach Monsey, closed shop several years ago, and other institutions survive by seeking to attract (horror!) “Frum From Birth” students (FFBs). A few years ago, Mishpacha Magazine signaled that the writing is on the wall: the door is closing on Jewish outreach.

The underlying reasons matter little for our purposes. But what is a trained kiruv professional, who spent years training to render the ideas of Judaism palatable to estranged brothers and sisters, to do with his or her skills?

The answer, I believe, lies in the invention of a paradoxical new vocation: kiruv kerovim. At a time when the general Orthodox community proves to be quite permeable to outside influences, outreach professionals have the rhetorical tools to explain the truth of Judaism in terms that are understandable to an acculturated audience.

Kiruv people, in other words, are builders of bridges between worlds. They are translators trained to explain the timeless in terms of the contemporary. They are uniquely positioned to “reclaim” tzeniut (or, for that matter, anything else) by retrojecting popular modern conceptions onto millennia-old Torah sources.

Reshuffling Ideological Camps

Other contemporary Western values emphasized throughout Reclaiming Dignity include the concepts of pluralism, tolerance, and inclusivity.[30] Beyond the porosity of values already observed, the insistence on a “diverse” mainstream Orthodoxy serves, fascinatingly, to redefine its outer limits.

Only a generation ago, the religious philosophy of Torah u-Madda was a wedge issue separating Centrist Orthodoxy from the Yeshiva world. No longer. As noted by Samuel Heilman,[31] Adam Ferziger,[32] and other scholars,[33] traditional divisions have become blurred in recent decades, as Modern Orthodoxy has undergone a so-called slide to the right and ultra-Orthodoxy more confidently engages with broader society. Each group, however, still struggles to define itself and to maintain age-old traditions in the midst of modernity, secularization, and technological advances.

This reshuffling of the cards is clearly visible in the target audience of Reclaiming Dignity, which comprises a wide range covering both “the Chareidi camp” and “the entire spectrum of Modern Orthodoxy.”[34] This assertion is to be taken utterly seriously: after all, the book boasts the imprimaturs of R. Zev Leff and R. Hershel Schachter. It quotes approvingly, a few lines apart, the words of R. Aharon Lichtenstein and those of Hazon Ish.[35] It draws from the ideas of R. Soloveitchik and R. Sacks but is distributed by Feldheim Publishers. The gulf that once separated Haredim from Centrist Orthodox people has simply evaporated. A new mainstream is taking shape in front of our very eyes.

This redefined “moderate mainstream” is bounded, on the right, by Hasidic communities, Israeli-Lithuanian communities, and Lakewood-type diaspora communities. These are not presumed to constitute the readership of the book, but their customs are to be respected.[36] On the left are communities whose halakhic observance is found wanting, but any criticism of them should be voiced respectfully.

Finally, one topic has recently become omnipresent in the Orthodox world: mental health. In Reclaiming Dignity, one finds everywhere the realization that extreme modesty practices are detrimental from a psychological standpoint.[37] This is certainly an effective argument for moderation, but it also raises grave questions: why should one respect extreme right-wing notions of tzeniut if these are mentally detrimental?

Shifting Limits of Gender Discrimination

Academic scholars and feminist activists have frequently denounced the patriarchal structure deeply ingrained in the norms of Jewish female modesty.[38] Research has yielded important insights pertaining to the objectification of women’s bodies, male anxiety over female power, and the gendered power dynamics of male rabbis regulating the bodies of their female constituents. Tzeniut is often perceived to be a cudgel against women and a tool for silencing their voices.

Interestingly, one of the essential messages conveyed by Bracha Poliakoff and Anthony Manning is that tzeniut is not just a woman’s mitzvah but rather a universal mitzvah that equally obligates males and females. This insight is reinforced in several ways throughout the book: the explicit subtitle of the book (“A Guide to Tzniut for Men and Women”); the large number of female essayists in the first part of the book; the inclusion of one halakhic chapter on “Tzniut for Men”;[39] and more. All of this strengthens the key idea that modesty is equally relevant for all human beings.[40]

The very notion that tzeniut applies irrespective of gender is, of course, yet another modern Western conception. Still, while the tone set by Reclaiming Dignity is completely sincere, the book sometimes falls short of its purported objective. Thus, the chapter on tzeniut for men is only 12 pages long, whereas its female counterpart (tzeniut for women) is discussed for hundreds of pages. And while women are invited to express themselves on “soft topics,” hard-core Halakhah clearly remains a male province.

Is the glass half full or half empty? Should the book be considered a step in the right direction, or a mere veneer of egalitarianism superimposed on a deeply patriarchal legal edifice? Readers will need to judge for themselves.

Conclusion

Reclaiming Dignity refreshes the message of tzeniut for one specific Jewish community: English-speaking, twenty-first-century Orthodoxy.

It is undeniably a thoughtful, sophisticated, and important book. Yet it remains an apologetic reinterpretation. In centuries past, Jewish communities did not think of tzeniut in these terms at all. Even today, French Sephardic Jews, Yemenite Jews, Old Yishuv Jews, and many others will only relate to some of Reclaiming Dignity’s messages, or to none at all.

“Apologetics” is not another word for “hypocrisy”: a good apology facilitates the transition from an older mindset to a more contemporary one. It makes it possible to incorporate modern moral insights while remaining loyal to tradition. From this perspective, Reclaiming Dignity is remarkably successful. Tzeniut-as-dignity is BOTH new AND traditional, and therefore, insofar as a religious tradition reinvents itself constantly, it is authentically Jewish.

Ideologically, we are witnesses to a fascinating new amalgamation of Jewish and Western values that is transpiring before our very eyes. Sociologically, Reclaiming Dignity reflects, or perhaps even crystallizes, a new alliance between previously warring factions of Anglo-Orthodoxy. It catalyzes powerful yet previously less visible social trends (an endorsement of mental health consciousness, limited concessions to gender egalitarianism, and a rejection of extremism and sectarianism).

Reclaiming Dignity celebrates the birth of a new Anglo-Orthodoxy and helps it find its own voice. Little wonder that such a rare book is greeted with unbridled enthusiasm.

Haym Soloveitchik has argued that important religious texts and concepts sometimes function as a mirror. People metaphorically “peer in” the Torah only to find their own likeness in its verses. As he puts it: “If this equivocality, this multivalence, is deep and complex enough, as it is in a few masterpieces, what are called ‘supreme works of art’, people then find themselves reflected in it. The work becomes, so to speak, all things to all men.”[41]

In my view, tzeniut possesses the same reflective capacity. Since the 1960s, rabbis and communities have repeatedly engaged in an exercise of self-projection. One can only speculate as to the shape that the next iteration will take, in 20 or 30 years from now: tzeniut for LGBTQ people? The laws of tzeniut by a female author? Or something else entirely?

The story of tzeniut, as it will be written in future decades, will be fascinating to observe―closely bound, as it is, with the story of Jewish Orthodoxy itself.[42]

[1] The concept of ervah (nakedness), as introduced in Berakhot 24a and later codified in the Shulhan Arukh (Orah Hayyim chapter 75), was always understood as a prohibition for men to recite the Shema or a blessing. It never anchored an obligation for women to cover their bodies. The first rabbinic authority who transformed the millennium-old “prohibition for males to pray” into a newfound “obligation for females to cover” was Hafetz Hayyim in his booklet Geder Olam (1892), an early precursor to the mid-twentieth-century legalization of tzeniut.

There exists a halakhic obligation for married Jewish women to cover their hair. This practice is already documented in the Mishnah (Ketubot 72a) and other tannaitic sources. However, as Dov Frimer has demonstrated in his doctoral dissertation, the practice was not originally understood as an expression of female tzeniut but rather as an obligation toward the husband and an expression of personal status. It is only in the Middle Ages that dat yehudit became an expression of female modesty. Until the revolution of tzeniut in the 1960s, Jewish law never regulated how observant Jewish women are expected to dress.

[2] Some of the themes of “tzeniut as dignity” were anticipated by Rabbi Norman Lamm. See his article “Tzeniut: A Universal Concept,” in Seventy Faces: Articles of Faith, vol. 1 (Hoboken: Ktav Publishing House, 2002), 190-199.

[3] A preeminent Canadian philosopher (born November 5, 1931). See Charles Taylor, “The Politics of Recognition,” in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition, ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 25–75.

[4] See Kiddushin 32b for a classical discussion about whether a rabbi, prince, and/or king can forgo their kavod.

[5] See, for instance, Berakhot 19b.

Kevod ha-beriyyot is a halakhic concept used to override rabbinic restrictions when their application would lead to embarrassing situations or otherwise unacceptable results (according to some opinions, this also applies to certain Torah prohibitions). For example, while carrying across a private property line is prohibited by a rabbinic restriction, the Talmud records that the rabbis created an exception, based on kevod ha-beriyyot, for carrying up to three small stones if needed for wiping oneself in a latrine (see Shabbat 81b, 94b).

These exceptions are strictly limited, both in their number and scope. The literature dedicated to this topic is vast. At any rate, kevod ha-beriyyot is clearly not the modern notion of dignity; as an illustration, see R. Yosef Karo‘s ruling that any clothing made of Torah-forbidden kilayim must be removed immediately, even though the other person was his rabbi and would end up entirely naked in the marketplace (Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh De’ah 303).

[6] Yair Lorberbaum has written an entire book on this very question: In God’s Image: Myth, Theology, and Law in Classical Judaism (Cambridge University Press, 2015). Per Lorberbaum, early rabbinic sources held anthropomorphic views of the human body as created in the physical likeness of God. In this approach, tzelem Elokim implies that humans are “living icons to the living God.” This conception had far-reaching implications for the formulation of the modes of execution, the biblical command to be fruitful and multiply, etc.

The concept of tzelem Elokim was then successfully reinterpreted by philosophers, kabbalists, etc. As Lorberbaum insightfully notes, all explanations of the phrase “the image of God” focus upon what the exegete regards as essential or unique in the human being (3). In other words, tzelem Elokim is mostly indicative of the exegete’s own anthropological conceptions. It is only in modern times that the expression became associated with the concept of human dignity.

[7] The quote is from Bracha Poliakoff, Reclaiming Dignity, 7. Similar (often identical) ideas are found in many other essays: see 11-15 (Rivka Simonsson), 16-17 (Miriam Kosman), 23-24 (R. Shaya Karlinsky), 44 (Rivkah Slonim), 46 (R. Chaya Chava Pavlov), 74-78 (Shevi Samet), 175 (Rifka Wein Harris), and so forth.

[8] The quote is from R. Efrem Golberg in Reclaiming Dignity (91). Here too, similar or identical ideas appear in many other places. See 6, 20, 67 (Michal Horowitz), 93 (Jaclyn Sova), 103 (Yael Kaisman), 163-165 (Faigie Zelcer), 168-170 (Elisheva Kaminetsky), etc.

[9] As captured by Charles Guignon, On Being Authentic: Thinking In Action (London: Routledge, 2004), viii.

[10] Reclaiming Dignity, 216.

[11] Reclaiming Dignity, 167-168.

[12] Reclaiming Dignity, 132. The emphasis on the word “me” is mine.

[13] To be fair, R. Manning’s third chapter discusses tzeniut as a way to live “lifnei Hashem” (233-254). But the point remains: in R. Manning’s view, the divinity is not the ultimate sovereign that commands absolute obedience but rather a spiritual presence that elevates human life. Readers are enjoined “to focus on our mental and spiritual awareness of the reality of God in our lives” (237). This is an anthropo-centered vision of God, not a theo-centered vision of man.

[14] See Shulhan Arukh, Even ha–Ezer 115.

[15] See Reclaiming Dignity, 297-347 and especially 310-312 and 341-343.

[17] Sylvia Barack Fishman, Jewish Life and American Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000), 10.

[18] “Daily learning is easy, in just 5 minutes a day!” See https://www.feldheim.com/modesty-an-adornment-for-life-day-by-day-2-vol.html.

[19] http://www.techeiles.org.il/ozvhadur/tests/test1.pdf.

[20] Pesach Eliyahu Falk, Oz ve-Hadar Levushah (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1998), 41 (the double-page 40-41 is a lengthy elaboration of this idea).

[21] Reclaiming Dignity, 317n53.

[22] See 248-249, 440, and 489.

[23] As far as I can tell, this is true of Miriam Kosman, Rabbi Shaya Karlinsky, Rebbetzin Tziporah Heller-Gottlieb, Rebbetzin Chaya Chava Pavlov, Sivan Rahav-Meir, Rabbanit Oriya Mevorach, Beatie Deutsch, Ilana Cowland, Rabbi Yitzchak Shurin, and Dr. Yocheved Debow. Ditto for Rabbi Anthony Manning, originally from London, who currently resides in Alon Shvut. And his teacher, the American-born rabbi Yitzchak Berkovits, serves (among other prestigious positions) as the mara d’atra of Jerusalem’s Sanhedria Murhevet neighborhood, where he lives.

[24] These numbers, of course, must be taken with a grain of salt. Moreover, I do not have dependable statistics regarding the number of British, Canadian, or Australian citizens living in Israel. And the comparison between Israel and the diaspora, if we want it to make sense in the context of Reclaiming Dignity, should only consider those who identify as Orthodox.

[25] R. Shlomo Aviner, Gan Na’ul: Pirkei Tzeniut (Jerusalem: Chava Books, 1980).

[26] R. David Stav and R. Avraham Stav, Avo Veitekha (Jerusalem: Maggid, 2020).

[27] R. Yitzhak Eizik Rosenbaum, Sefer ha-Tzeniut ve-Hayeshuah (Jerusalem: 1980).

[28] Falk, Oz ve-Hadar Levushah.

[29] Rabbi Shaya Karlinsky, Rebbetzin Tziporah Heller-Gottlieb, Rivkah Slonim, Rebbetzin Chaya Chava Pavlov, Yael Kaisman, Ilana Cowland, Rabbi Yitzchak Shurin, and Shalvie Friedman.

[30] For examples, see Reclaiming Dignity, 8, 208, 343, 357-359, 491-492, etc.

[31] See Samuel Heilman, Defenders of the Faith: Inside Ultra-Orthodox Jewry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Samuel Heilman, Sliding to the Right: The Contest for the Future of American Jewish Orthodoxy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[32] Adam Ferziger, Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2015).

[33] Haym Soloveitchik’s classical article is now a full-length monograph: Rupture and Reconstruction: The Transformation of Modern Orthodoxy (London: Liverpool University Press, 2021).

[34] Reclaiming Dignity, xxxi-xxxii.

[35] Reclaiming Dignity, 203-204.

[36] Reclaiming Dignity, 342-343.

[37] See the neologism “tzniut PTSD” (3, 111), the discussion of “hashkafah anxiety” (357-359), and more.

[38] There is a vast literature that cannot be exhaustively listed here; see in particular Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2007), 45-61. And Tanya Regev’s unpublished doctoral dissertation, “‘Men Act and Women Appear’ (John Berger): The Formation of Feminine Identity in Writing about the Ethos of Modesty in Religious Zionism” [Hebrew], (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University, 2021).

[39] Ibid., 503-515.

[40] This plays into the themes examined above: unless modesty is extended to men and reconceptualized as universal, it cannot be explained as an expression of fundamental human values such as internality, dignity, authenticity, etc.

[41] Haym Soloveitchik, Collected Essays II (London: Liverpool University Press, 2019), 388.

[42] I would like to thank my wife Dr. Sarah Bloch-Elkouby, Dr. Leslie Ginsparg Klein, R. Dr. Tzvi Sinensky, R. Dr. Moshe Miller, Prof. Chaim Saiman, and Ashley Stern Mintz for making very useful remarks to earlier versions of this essay.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.