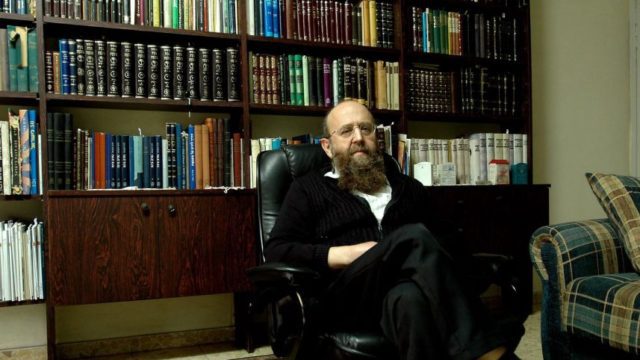

Yehuda (Udi) Dvorkin

As a student of Rav Shagar’s thought and an instructor at his yeshiva, I read with great interest the various articles published at The Lehrhaus on Rav Shagar’s thought. It is impossible to summarize such a complex thinker as Rav Shagar’s in one short essay, and I do not think there is need nor interest in my defending his teachings. Still, my sense is that it will still be helpful to share a few thoughts relevant to this ongoing discussion.

Rav Shagar’s Thought, Publications, and English Publications

First of all, it is important to note that the publication of Rav Shagar’s thought has only just begun. The Institute for the Advancement of Rav Shagar’s Writings has published eighteen books, but many more volumes stand to be published, on tropics ranging from his lectures on Moreh Nevukhim to Hasidut, to halakhah, to more Talmud analyses.

The state of publication of his work in English is far behind the Hebrew. Several articles have been translated and/or analyzed at Alan Brill’s Kavvanah blog, The Lehrhaus, and on other sites. Most recently and prominently, the recently published translation of several of Rav Shagar’s core essays by Maggid Books, Faith Shattered and Restored: Judaism in the Postmodern Age, has offered a service to the English-speaking reader, making some of the more important essays available.

I hope that there are both more publications in English of Rav Shagar’s work and more discussion of the meaning of Postmodern Orthodox in the future. But we must be clear about the fact that those who have not read his Hebrew publications (and even those who have!) are attempting to understand the man and his approach based on a limited corpus of evidence. This is not to disqualify anyone not familiar with all of Rav Shagar’s writings from holding an opinion or participating in the conversation, but it is important to note that many of his teachings are not yet publicly available.

Rav Shagar on Subjectivity

I grew up in Jerusalem, with minimal exposure to postmodernism or the conception of a narrative-based society. I found myself, as did many others of my generation, asking tough questions about Jewish identity and belief, halakhah, and gender issues. I sought answers.

This quest led me to move, both geographically and religiously, between communities, denominations, and approaches to Judaism. Wherever I looked, people claimed they had all the answers. Clear answers. Definite answers. They knew precisely the approach to take, the halakhic revolution that would resolve any lingering problems. Some of these approaches were persuasive, authentic, and real. But I found myself always asking another question, raising another reality at odds with this approach.

It is only when I arrived at Yeshivat Siach Yitzchak that I encountered an institution, co-founded by Rav Shagar, that didn’t claim to have all the answers. Its current Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Yair Dreifuss, was more focused on listening and asking questions rather than providing answers. Not only were my experiences subjective to him, but his thoughts on them were subjective, as well.

As I invited him to listen to my narrative, He made it clear he can only relate to it from within his narrative and experience and that he cannot give an objective opinion but rather engage in an attempt to understand my narrative.

Subjectivity is dangerous. It is always relative and never definite. It assumes that our narrative is only our narrative, and that it is not necessarily a part of an all-encompassing truth. It allows reality to shift in form, and allows people to view reality through their own eyes. If we believe halakhah and tradition are eternal, then how can we reconcile this with people’s divergent realities? More importantly, do we want to reconcile them?

Rav Shagar negated this question entirely. He understood that we must live fully as Jews while remaining within our personal narrative. We live in a world where our freedom to act subjectively is perhaps the last truth. He saw the world as it is, including the impossibility of demanding that anyone give up on their experience or objectify their life.

The condition for a covenant with the Other is my belief in his freedom: that it will not impinge on mine and will truly lead to what is good. Only thus can I recognize the Other as a subject, without objectifying him. That is the deep meaning of recognizing the other’s divine image. It requires seeing to the root of the other’s soul on high, at the level of consciousness known as yeĥida, above all physical and spiritual garments. (Faith Shattered, 84).

Belief, Not Knowledge

In our postmodern world of competing Narratives, halakhah is only one of many. It is also true that we are unable to make halakhah objective, as we have lost the ability to speak of objectivity. But what if we are not expected to make halakhah objective? Maybe our obligation is not to view halakhah as the inevitable truth but to choose to remain our tradition. To see halakhah as important because it is our tradition and our truth, based on our subjective experiences.

In the postmodern experience, we no longer compete with other religions or denominations for the absolute truth, but struggle internally to determine our personal truth. We thus have the option to choose to live in a narrative where God’s word is our Torah, where halakhah is our way, and where history was written at Sinai.

We don’t know. We believe.

If the modern world asks humanity to choose between faith or knowledge, to build overarching, objective superstructures, the postmodern world rejects this completely. It allows us to believe and to return to a more traditional sense of faith:

My encounters with various believers and nonbelievers will not weaken my belief, but rather strengthen it, for contending with the outside view of my faith has the power to free it of its subjectivity. Moreover, the process of becoming acquainted with alternatives to my own faith, and choosing it anew nonetheless, allows me to form a “face-to-face” bond that is more exalted than the superficial “back-to-back” relationship … Traditional theological debates that sought absolute, transcendental criteria to determine which belief reigns supreme are meaningless in a postmodern world, but that should not impugn our perseverance in the faith of our fathers (Faith Shattered, 117).

Rav Shagar on Pluralism

Rav Shagar was not a pluralist. Pluralism, at its core, attempts to bridge the gap between the objective reality of truth and the possibility or desire to accept multiple objective truths. The pluralist’s solution, asserting the existence of a multiplicity of truths is modern to the core, at least in its original version. Postmodernism, at least for some of its thinkers (and critics), deconstructs the idea of a real, objective truth, thus negating the entire question.

I can live within my narrative where I truly believe my way is right and others are wrong. However, simultaneously, be-neshimah ahat, I am not invalidating other narratives. Narratives that believe I am wrong. Yes, this is a paradox. But it is the paradox of our time. In one of Rav Shagar’s teachings of the Akedah he writes

A conceited, all-knowing religious stance renders the trial, and with it the entire religious endeavor, a sham. The trial, along with a religious lifestyle and a connection to God, can exist only in the context of a humble personality that is content in not knowing. A conceited stance stems from pride, and it is the voice of Satan. The trial will forever be associated with a subject who by nature is in the dark. The objectivization of the religious trial invalidates it. Hence Abraham’s response to Satan: Although he is aware of the objective truth, he does not allow his knowledge to detract one whit from the gravity of the trial (Faith Shattered, 13-14).

In a postmodern era, where we are challenged not to make our awareness become truly objective in our life, our sacred subjectivity is our trial. We ought not to objectify our dalet amot, our halakhah, but to live humbly within in it. That same humility can also help us see the Divine in everything.

Judging Others Favorably

We live in a world where limmud zekhut, finding the merit in others and judging them fairly, is sorely needed.

Some have argued that an approach which sees the Divine in everything is liable to lose its grip on Halakha. However, such a loss of faith is due not to a particular theological or postmodern approach but to the very era we are living in. We live in a world where, rather than joining organized, traditional religion, people are either choosing to live without faith or are creating their own personal ”faiths.”

Robert Bella and Richard Madsen describe this phenomenon they call “Sheilaism” in their Habits of the Heart. One might see this reality as negative, but it is nevertheless our reality. Our only option is to choose our religion from within our narrative. Rav Shagar did not fear this moment in our history but saw it as an opportunity for finding a deeper faith.

In our world, we cannot turn to our students, who live and breathe a world without boundaries, and tell them that there are clear, objective boundaries. We must listen to their experiences, to their narratives and look for the Divine within. The shattering of the modern world into an infinite number of narratives, stories, and opinions—each of which is part of reality, (or maybe of infinite realities)—creates something new. This provides an opportunity, a real possibility for emunah, for a deeper faith. Where every human experience becomes a narrative, it is only Hashem that remains certain:

We come to understand that that which exists is the result of one outcome out of millions of possibilities contained in the Infinite, Blessed Be He. Thus relativism leads to a kind of faith on a mystic level: at this level, mysticism is not a game or a pretense, but an expression of the myriad possibilities that are inherent in the Divine. The crisis of postmodernity can thus break idols and statues—for nothing is absolute but God himself—and bring us closer to an unmediated encounter with God (Luhot ve-Shivrei Luhot, 401).

Postmodern Messianism?

We live in a complicated time, but also one that allows for optimism, maybe even messianism. This shattering and proliferation of truths can lead us to a reality of a multiplicity of understandings of God, ka-mayim la-yam mekhasim, “as the waters cover the sea” (Isaiah 11:9). Just as no one drop defines the ocean but we know it is a part of the ocean when we see it, we might not see how each narrative comprises the Divine, but viewed holistically it is clear.

Are there risks? Certainly. Do we have all the answers? No. We can only trust and believe. In today’s reality trusting in ourselves is the only option. As Rav Shagar puts it:

Rav Yoelish disqualifies the authoritative, exclusive power of the leading rabbis to determine the ‘true’ Torah path, and instead describes his time as one where “the generation leads its leaders.” Therefore, his personal credo—one that he shares with those who turn to him—is to know how to act according to one’s internal truths of knowledge and righteousness.

This advice seems to me especially pertinent for our chaotic world, in a time when the Jewish world presents so many divergent, conflicting paths. It is then that man is called to act with integrity, following an internally-directed upright Judaism, believing with both humility and certainty that he is doing that which G-d has demanded. There is no requirement for man to ‘cheat’ himself, as it were. At the same time, any ‘truth’ can easily be there one moment and gone the next. But if he acts with integrity and honesty and prays to G-d to protect him from failure and misled beliefs, then even if he has “erred” he is not truly making an error: for that is what God asks of him in an era when “man does what is right in his eyes” (Lessons on Likutei Moharan, 349-350).

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-100x75.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.