Mark Trencher

Important new research is being done in the Orthodox community. Issues of substantial concern—which have been largely overlooked by the larger, oft-cited Jewish community surveys—are being explored, and the community is beginning to develop information that will be helpful in making informed decisions.

While the research approaches being taken are not perfect, it would be a shame to allow naysayers to deflect from the value and experience being obtained. Most recently, Matthew Williams made some valid points, but his article reflected a lack of appreciation of how and why previous research has not met the Orthodox community’s needs, and some of his statements were incorrect.

Full Disclosure: I am the principal analyst and author of “The Nishma Research Profile of American Modern Orthodox Jews” (September, 2017), and my comments will largely relate to that study. Williams also cited the more recent “Survey of Yeshiva High School Graduates” (January, 2018), conducted by Zvi Grumet of the Lookstein Center.

Why this Research has been Long Overdue

There have been only scattered efforts to conduct quality research into the issues most relevant to Orthodoxy. As a result, institutions in the Orthodox community often make decisions without access to any research, or they may rely on poorly done research; alternatively, they may explore sources like Pew Research Center’s 2013 study of American Jews, although it reached only 154 Modern Orthodox respondents.

Williams took issue with the Nishma survey’s stated 95% accuracy range of ±1.7%, noting that the sample was not representative enough to warrant this figure (I will address the representativeness of the Nishma survey sample below). However, the Pew Survey 95% accuracy range for its Modern Orthodoxy sample is in fact much wider, at ±8%. That small sample of Modern Orthodox is more problematic if one wants to look at such differences as men vs. women, by age, or by group within Modern Orthodoxy. The sample is too small to allow for much slicing in this manner, with the result that few differences will be statistically meaningful.

Covering the Relevant Issues

Jewish communal surveys typically cover many issues aimed at the broad spectrum of Jews, including Conservative, Reform, etc., and devote only a small part of the survey to the issues, attitudes, and concerns that are particularly—and often uniquely—relevant to Modern Orthodoxy.

For example, Nishma found the #1 concern among Modern Orthodox Jews was the high cost of Jewish education. This was explored in neither Pew nor the other major study of recent years, the UJA Federation’s “Jewish Community Study of NY 2011” (JCS). The #2 issue that concerned Modern Orthodox Jews was the plight of agunot (“chained women” unable to remarry because they have not received a gett, a religious divorce); again, an issue that was a “no show” in the communal studies. The #3 issue of concern was religious people not dealing with others with appropriate middot (proper behaviors), followed at #4 by the cost of maintaining an Orthodox home. Of the 27 areas of possible concern listed in the survey, 16 were specific to the Orthodox world.

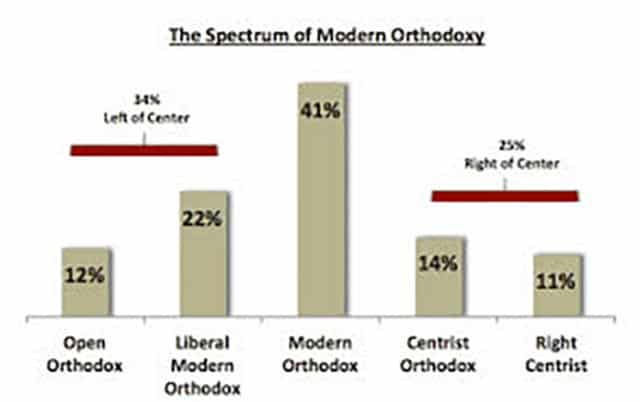

In general, the issues of concern to Orthodoxy are not covered or, at best, glossed over in the major communal studies. Additionally, those studies treat Modern Orthodoxy as a homogeneous group. This is far from true, as Modern Orthodoxy covers a wide span from Open Orthodox, through liberal and centrist groups, to some that tend toward more yeshivish attitudes and behaviors. The Nishma survey explored these subgroups and found very large differences in beliefs, practices, and attitudes across Modern Orthodoxy. We aimed for a large sample in order to enable exploration of the differences across Modern Orthodoxy with high statistical validity.

Surveys like Pew and JCS give us an understanding of such issues as how often Jews visit their Jewish Community Center, send their children to a Jewish day camp, and whether their household had a Christmas tree last year. These are important issues in understanding American Jews and their connection to the Jewish community and practices, but they do not resonate with or inform the Orthodox community (which makes up 11% of American Jewry) or the Modern Orthodox (which comprises 4%) in any meaningful way.

These small percentages may explain why the communal surveys devote little attention to the issues that are specific to Orthodoxy. Unfortunately, we have fallen by the wayside in the research world; however the recent surveys are steps toward ameliorating that oversight.

Making Lemonade Out of Lemons

The Nishma survey questionnaire was developed by an advisory group of academics, sociologists with expertise in the Jewish community, Modern Orthodox rabbis, lay leaders, and educators. This was done to ensure that the survey addressed the issues facing Orthodoxy, most of which had not been explored in any organized study of the community.

The survey reached 3,903 American Modern Orthodox Jews, a strong response that reflects the community’s interest in being heard, and that allows for deeper analysis of differences among groups. How was this done? And is the sample representative and reliable? Simply put, were we able to make lemonade out of lemons?

There is no “list” of Modern Orthodox Jews available to researchers. Pew notes that the “low incidence (of Jews in the population) means that building a probability sample of U.S. Jews is difficult and costly.” What Pew did was to: (1) draw upon prior survey results to identify about 1,700 U.S. counties that have at least 0.25% Jewish population; (2) make 71,151 phone calls to screen people as to their being Jewish; and (3) ask those identified to take the telephone survey. In the end, 3,475 people took the survey, including 154 Modern Orthodox.

Williams was appropriately critical of internet-based opt-in surveys that rely on social media. He seemed to imply that the Nishma survey used social media; it did not. Reaching out to people by calling or otherwise contacting them (an approach that researchers describe as “opt-out”) is the much-preferred way to conduct a sociological study. Alternatively, a study released through social media—for example, by posting links to an online survey at Facebook pages—is known as “opt-in” and has been shown to generate more biased (i.e., less representative) samples.

But there is a reality … based on the Pew experience, we would have had to make 925,000 phone calls to obtain the desired 2,000 Modern Orthodox respondents that would provide for meaningful analysis of the subgroups. That was clearly not doable.

To reach our target audience, we drew upon the virtual universality of synagogue attendance and/or affiliation among Orthodox Jews. Phase 1 was to carefully select 30 Modern Orthodox synagogues across the US, across geographic, denominational, and size categories, which agreed to send the survey to their members. Phase 2 was the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA) reaching out to its hundreds of Modern Orthodox rabbis, many of whom, in turn, invited their synagogue members to participate in the survey.

The language that synagogue members received in an email invitation simply noted in neutral language that this survey was going to be taking place, mentioned some of the topics, and encouraged them to participate by clicking on a provided link. Nishma did not solicit responses via social media because we wanted to avoid skewing the sample by disproportionately drawing upon those with pet issues or complaints.

Admittedly, this was an opt-in survey. We follow the guidance of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) to the effect that opt-in surveys are not ideal. However, given the small size of the Orthodox (0.25% of the US population) and Modern Orthodox (0.1% of the US population), the lack of any lists that can be used to create an opt-out mechanism, and the huge cost of methods such as those used by Pew, a well-designed opt-in survey was judged to be the most viable option. We are transparent in sharing our methodology because we believe it was the best possible approach at this stage in the development of Orthodox world research.

One more observation: The findings have been shared in presentations and weekend programs at a number of shuls, and people’s reactions are that the findings ring true. They may like or dislike what they hear (and there is often a vibrant discussion), but I have not yet heard anyone say that the findings seem inconsistent with what he or she has observed in the community.

Some Corrections

A few of Williams’ comments warrant correction:

- He wrote: “The studies assume a constellation of ‘core’ values but this does not allow for space or opportunity for participants to offer their own definitions of behaviors and beliefs. As a result, both surveys provide less data about the sampled population.” We believe strongly in the value of open-ended questions, and The Nishma Research study provided respondents with the opportunity to comment at great length regarding their beliefs and practices. We have several lengthy documents available online, including an 84-page document in which people go into great detail on their beliefs as well as aspects of Orthodoxy that give them satisfaction and those that cause unhappiness. I strongly recommend that people read this thought-provoking document.

- Williams criticized some of the language, citing as an example the use of terms like “OTD” or “Off the Derekh.” Our survey did not include this term (nor did we use it in our 2016 Survey of Those Who Have Left Orthodoxy). He also cautioned against the “alienation of potential respondents” and “rhetorical flavor.” I agree; our language was carefully vetted, in the survey questionnaire as well as the reporting.

Don’t Let “Perfect” Get in the Way of “Good”

Clearly, opt-out surveys are superior to opt-in surveys and should always be the goal. However, there are situations where we need to be creative and do the best we can, drawing upon available resources while taking steps to maximize sample representativeness and minimize bias. This is especially challenging when dealing with a statistically minute population.

Nishma means “listen” and I encourage people to read the report. Its goal was to get people thinking about these issues and it is doing so. Read through these new reports, continue to question, seek to understand, and get productive dialogue going within the community.

Don’t let “perfect” get in the way of “good.” Let us built on what we are learning.

Finally, the time has come for the Orthodox community to find the resources to do high quality research. It should be a communal imperative, and not just a labor of love by a few dedicated researchers.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.