David Matar

Rabbinic collections are replete with fascinating stories that recount pivotal events in Jewish religious and political history. One such event was the first recorded appearance of the famous sage Hillel on the national stage, when he ruled on a halakhic question with regard to the offering of the Passover Sacrifice in the Temple.

This rabbinic story has come down to us in three versions: The original recension as told by Tanna’im in the Tosefta (Pesahim 4:13-14); a later adaptation and retelling by Amora’im of Eretz Yisrael in Talmud Yerushalmi (Pesahim 6:1); and a still later reworking of the Yerushalmi version by Babylonian sages that can be found in Talmud Bavli (Pesahim 66a). Much scholarly attention has been devoted to the differing goals and ends of the Amoraic editors in the Yerushalmi and the Bavli. In this essay, I will attempt to show that the original Tosefta version is itself edited and adapted from an even earlier tradition, a version that has not come down to us. Moreover, several obvious omissions and inconsistencies in the Tosefta version will lead me to a likely reconstruction of the dramatic events in Hillel’s time that constituted no less than a revolution in the governance of the Second Temple.

Here is the relevant text from the Tosefta,[1] divided into three parts:

1. Once, the 14th (of the month of Nisan) fell on the Sabbath. They asked Hillel the Sage, “The Passover Sacrifice – Does it override the Sabbath [laws]?” He said to them, “Is there only one ‘Passover Sacrifice’ a year that overrides the Sabbath? We have more than 300 ‘Passover Sacrifices’ a year that override the Sabbath!” The entire [Temple] courtyard banded together against him.

2. He [Hillel] said to them, “The Tamid, daily sacrifice, is offered by the public, and the Passover Sacrifice is offered by the public; just as the daily sacrifice is offered by the public and overrides the Sabbath, so too the Passover Sacrifice is offered by the public and overrides the Sabbath. Another argument: It is said [in the Scriptures] with regard to the daily sacrifice that it is offered in mo’ado, its appointed time, and it is said with regard to the Passover Sacrifice that it is offered in mo’ado, its appointed time; just as the daily sacrifice, where mo’ado is mentioned, overrides the Sabbath, so too the Passover Sacrifice, where mo’ado is mentioned, overrides the Sabbath. Additionally, one can make an argument a fortiori: If the daily sacrifice, where there is no punishment of Divine excommunication (for non-performance), nevertheless overrides the Sabbath, certainly the Passover Sacrifice, where non-performance is punished by Divine excommunication, overrides the Sabbath. In addition, I have received a tradition from my teachers that the Passover Sacrifice overrides the Sabbath. [This is true] not just for the first, or original, Passover Sacrifice (offered in Nisan), but also for the second, or alternative, Passover Sacrifice (offered a month later in the month of Iyyar); and [this is true] not just for the Passover Sacrifice offered by the public [in the Temple], but for the Passover Sacrifice offered by individuals [outside the Temple].”

3. They said to him, “What will be with the people, who have not brought their knives or their Passover Sacrifices to the Temple?” He said to them, “Let them be. The Divine spirit is upon them; if they are not themselves prophets, they are the sons of prophets.” What did Israel do at that time? He whose Passover Sacrifice was a lamb, buried [the knife] in its wool; he whose Passover Sacrifice was a kid, tied it [the knife] between its horns. And they brought their knives and Passover Sacrifices to the Temple, and slaughtered [there] their Passover Sacrifices. On that same day, they appointed Hillel as the Prince (Nasi) , and he instructed them in the laws of Passover.

To understand this rabbinic story, a short history of the Passover Sacrifice from its inception to the era of Hillel is in order. The Passover Sacrifice first appears in Exodus 12 as a divinely mandated ritual that proved central to the redemption of the Israelites from their Egyptian bondage. This sacred ritual was carried out in two stages: In the first stage, every head of an Israelite household obtained a one-year-old lamb, slaughtered it in the afternoon of the 14th of Nisan, and then smeared the lamb’s blood on the doorframes of his home. This bold demarcation enabled the Lord to spare the Israelites when He passed through the land of Egypt at midnight on the night of the 15th of Nisan, in order to strike down the firstborn and the gods of Egypt. The second phase of the ritual was a family feast, where the sacrificial lamb was roasted and eaten in its entirety by the members of each household; the original Passover lamb was eaten with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, and was consumed in great haste, as this was the last meal before the Israelites set forth on their miraculous journey out of Egypt.

The first Passover Sacrifice is known as Pesach Mitzrayim – the Passover Sacrifice of Egypt; however, this sacrifice was never meant to be a one-time offering, but rather an everlasting law (Exodus 12:14), publicly celebrated on an annual basis as Pesach Dorot – the Passover of generations to come. In the years that followed the Exodus from Egypt, the holiday of the Passover Sacrifice on the 14th of Nisan was connected to the separate seven-day holiday called Hag Ha-Matzot, the Festival of Unleavened Bread. The festive family meal on the night of the 15th of Nisan, when the Passover lamb was eaten, became the initial celebratory feast of the Festival of Unleavened Bread; the sages of the Mishnah and Talmud gave the meal a religious and educational dimension, and made the Passover Seder a central feature of the Jewish calendar.

According to Scripture, the very first Pesach Dorot was celebrated by the Israelites in the Sinai desert on the first anniversary of the Exodus from Egypt (Numbers 9:1-5). We next hear of the Israelites performing the Passover Sacrifice in their encampment at Gilgal, after they entered the Promised Land under the leadership of Joshua (Joshua 5:10). Deuteronomy 16:1-8 insists that the Passover Sacrifice be offered only “at the place that the Lord will choose as a dwelling for His name” – that is, at the Temple in Jerusalem. However, it seems that the offering of the Passover Sacrifice as a public ceremony at the Temple was honored more in the breach than in performance throughout the First Temple period. Only in the generation before the destruction of the First Temple did King Josiah organize a mass Passover Sacrifice as the centerpiece of a religious revival that reaffirmed and renewed the people’s covenant with their G-d. The Book of Kings (II Kings 23:21-22) reports that Josiah commanded all of the people to perform the Passover Sacrifice “as written in the book of the covenant,” and comments: “Now, no such Passover Sacrifice had been made since the days of the judges who ruled Israel, nor during all the days of the kings of Israel and Judea.”

Whatever the fate of the public Passover Sacrifice in the First Temple period and the subsequent Babylonian exile, we do know that, with the return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple, the Passover Sacrifice served an important role in bringing the returned exiles to the Temple “to seek out the Lord, the G-d of Israel” (Ezra 6:21). We have no written sources that document the 400 years from the days of Ezra in the mid-5th century BCE to the days of Hillel in the late 1st century BCE, but the rabbinic literature assumes that, during this period, Passover Sacrifices were brought annually to the Temple courtyards in Jerusalem by havurot, dedicated family groups, from all over Israel and the diaspora.

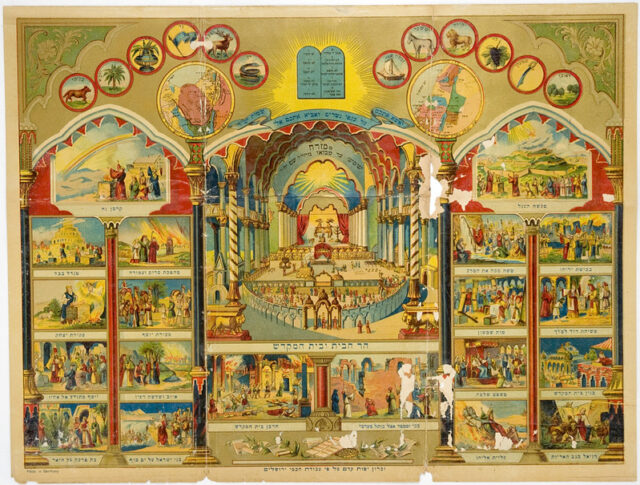

The Mishnah (Pesahim 5) paints the Passover Sacrifice in the Temple as an impressive and majestic spectacle. Representatives of each havurah arrived with their lambs at the Temple on the afternoon of the 14th of Nisan, and were ushered into the inner courtyard in three successive groups. Representatives of the havurot in each group slaughtered their animals in the inner Temple courtyard. Then the Temple priests received the animals’ lifeblood in gold and silver vessels; they then conveyed the blood through a human chain of priests to the altar, where a designated priest threw the blood of the sacrifices onto the foundation of the altar. The Temple priests also burned the fats of the Passover Sacrifices on the altar. Trumpets were blown at the beginning of the sacrificial process, and, throughout the ritual, those who brought the sacrifices sang the Hallel, psalms of praise (Psalms 113-118), in the Temple courtyard accompanied by the professional Levite singers.

Our story in Tosefta Pesahim posits a situation where the designated day of the Passover Sacrifice, the 14th of Nisan, fell on the Sabbath. The narrative implies that the ritual was canceled or suspended by the Temple authorities, most likely on the grounds that elements of the sacrificial process, such as the act of slaughtering, violated the Sabbath laws. In a last-ditch effort to reverse this ban and bring the masses to the Temple courtyards to offer their Passover Sacrifices, unnamed persons approached the prominent Pharisaic sage Hillel during the Sabbath that fell on the 14th of Nisan and spoke to him in the Temple precincts. Phrasing their request as a halakhic query, they in effect asked Hillel to convince the priestly administrators of the Temple to allow the sacrificing of the paschal lambs despite the Sabbath prohibitions. Hillel agreed to support this initiative, but before he could marshal his arguments he encountered determined opposition; we are told that ‘the entire Temple courtyard’ banded together against him. This unique phrase can only mean one thing: the priestly administrators, who were present at the time in the Temple courtyard, united in order to frustrate the demand made in the name of the people, opposing the offering of the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath.

Why did the chief priests oppose the initiative of the people and their advocate Hillel? I suggest that we identify the recalcitrant priests who banded together against Hillel in the Temple courtyard as members of the sect of the Sadducees, an aristocratic priestly caste who controlled the Temple administration for some two hundred years – from the reign of the Hasmonean king Yohanan Hyrcanus (134-103 BCE), through the era of Hillel (flourished circa 30 BCE), until the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE). The Sadducees are often portrayed in rabbinic literature in a negative sense, as opponents of the Pharisaic sages in the determination of the halakhah in and outside the Temple, and as deniers of basic theological doctrines of the Pharisees, such as faith in the afterlife and in the resurrection of the dead. The Sadducees, however, saw themselves in a positive light, as faithful guardians of ancient traditions that had been customary in the Temple for most of the First Temple and Second Temple periods. These traditions were gathered and transmitted by the High Priests of the House of Tzadok, a prestigious priestly dynasty named after the High Priest who served under King Solomon, builder of the First Temple.

The Sadducee heads of the Temple who confronted Hillel saw the Passover Sacrifice as an anomalous and problematic phenomenon. This sacrifice had originated outside the Temple as a familial offering that was slaughtered and eaten near the home; this semi-private sacrificial process was only introduced into the Temple precincts at a later date. The Sadducees relied on internal and autonomous Temple traditions that contradicted Hillel’s casuistic arguments, and therefore did not equate the Passover Sacrifice with the daily offerings (which were indeed routinely offered on the Sabbath). Hillel’s rhetorical brilliance left the priests in the Temple courtyard unimpressed, since they did not possess a specific internal tradition that would legitimate the offering of the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath.

In the end, the priests were cowed only by Hillel’s assertion that he had received the requisite tradition independently from his Pharisaic teachers. Hillel claimed that the locus of authority as far as Temple ritual was concerned was not centered on the Temple priesthood and their traditions; popular traditions transmitted by the Pharisaic sages are to be considered as even more authoritative than Temple traditions.

Despite Hillel’s triumph in forcing the Temple priests to agree in principle to offer the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath, a practical halakhic problem now came to the fore: those who had pushed Hillel to intervene on their behalf with regard to offering the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath were not prepared for the unforeseen victory of their champion, and had left at home the lambs, kids, and the slaughtering knives needed for the sacrificial act. The people were concerned that bringing their animals and knives to the Temple would violate the Sabbath laws with regard to transporting objects between domains as well as within the public domain. Once again, questioners turned to Hillel for a solution, but, in this instance, he did not have a tradition at hand that would circumvent the prohibition against carrying items on the Sabbath.

Hillel was now forced to abandon his original argument from a competing tradition, and boldly make a radical, even revolutionary, claim. Hillel declared that the common people of Israel act in the public sphere as inspired by the Divine Spirit. The statement that the people of Israel are, if not prophets, at least the sons of prophets, is extraordinary, for these ‘sons of prophets’ and their representatives – the Pharisaic sages headed by Hillel, could exploit their prophetic status to create new traditions that override and replace ancient traditions of the Temple priests! One should note that once Hillel had come so far in his rhetorical journey as to claim for the people the authority normally reserved for the prophets of old, that he no longer needed to rely on the traditions he had received from his teachers with regard to bringing the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath.

Hillel’s new argument marked a turning point in the administration of the Temple. No longer would decisions about ritual be governed by internal traditions of the Sadducees that were supposedly of prophetic origin. The Pharisees led by Hillel advanced an alternative line of authority that lent Divine sanction to any custom or legislation that enjoyed wide popular support. In the balance of power between the Sadducees and Pharisees, roles were reversed: Sages were no longer intimidated by ancient priestly traditions, so long as they could invest popular practice with the authority of prophecy and the plausible rationale of casuistic arguments. These new ‘traditions’ of the Sages would come to reshape Temple ritual.

Both the Yerushalmi and the Bavli adaptations of this story do not admit the circumstances reflected in the Tosefta, that an internal tradition of the Temple priesthood negated the offering of the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath. Both sources assume that the Sages, not the priests, were in control of the Temple from the days of Ezra the Scribe, and therefore posit that the crisis arose when the chief Sages of Hillel’s time had simply forgotten what had been done in the Temple the last time the 14th of Nisan fell on the Sabbath. This interpretation of events is hardly tenable on its face. After all, according to astronomic calculations, the 14th of Nisan falls on the Sabbath roughly once in fourteen years; if the Sages were really in charge of administering the Temple, any and all legal precedents would be enshrined in rabbinic tradition rather than forgotten! It would seem that later talmudic editors of the Yerushalmi and the Bavli projected their own post-Temple reality onto the Tosefta story, and were no longer aware of clashes between the Sadducees and Pharisees in the Temple. Thus, they moved the locale of the controversy over the offering of the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath from the courtyard of the Temple to the rabbinic study hall, and explained ignorance of the law by positing that senior Sages had forgotten their own traditions and precedents.

Truth be told, the fateful conflict between the Sadducees and Pharisees over control of the Temple ritual is not clearly delineated in the Tosefta text; the protagonists are referred to obliquely, and any mention of their motivations is entirely suppressed. Thus, the vigorous opposition of the priesthood to Hillel’s initiative is cloaked in the vague description of ‘the entire courtyard banding together.’ Moreover, the persons who sent Hillel into the fray against the Temple leadership are never named throughout the story; “They” asked Hillel about offering the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath, and those same anonymous figures said to him that there was still an issue of bringing animals and knives into the Temple on the Sabbath. Presumably, these same unidentified persons appointed Hillel as the Nasi – a semi-royal title that denotes leadership.

In order to clarify the meaning of the Tosefta, we must ask: Over which group was Hillel appointed Nasi? The answer lies in the identification of the mysterious persons who spoke to Hillel. If we posit that these people were the leaders of the sect of the Pharisees who sent their colleague Hillel to battle their Sadducee rivals, we will conclude that Hillel was appointed leader of the Pharisees – that is, chief of the Sages of that generation. However, it is more likely that representatives of the masses were the ones who approached Hillel; these were spokesmen for all those common people who had prepared lambs and knives in their homes but were not allowed to bring their sacrifices to the Temple on the Sabbath. It seems clear from the course of events in our story that the pressure for change in the laws of the Passover Sacrifice came from below, for Hillel gave credit to the people (and not his fellow Pharisees) as “sons of prophets” who knew how to solve halakhic problems that they encountered. According to this approach, Hillel was appointed Nasi over all those who benefitted from the change that he brought about in the Temple – that is, the masses who sought to offer their Passover Sacrifices in the Temple.

The appointment of Hillel as the Nasi over the people and by the people serves as the coda to this story, and in fact functions as its point and object lesson. The Mishnah (Avot (1-2) traces a dynastic line of scholarly leaders from Hillel (30 BCE) to Rabbi Yehudah Ha-Nasi (180-220 CE) and beyond, until the end of the dynasty in 429 CE. The halakhic and administrative authority of the Patriarchal dynasty, exercised over some 17 generations and 450 years, rested to a great extent on the claimed descent of the family from the iconic sage Hillel. For advocates of the Beit Ha-Nasi, thePatriarchate, the popular acclamation of Hillel as Nasi set a precedent that legitimated the rule of his descendants over scholars and commoners alike in all following generations. In the era of Rabbi Yehudah Ha-Nasi in the early third century, a further claim was circulated by the patriarchal court: Hillel was himself descended from King David, and thus the institution of the Patriarchs took on royal and messianic overtones.

In order to turn the appointment of Hillel into a binding precedent, it was necessary for the Toseftan editors of this story to hide the sectarian background of Hillel’s political victory as much as possible. Since the Sadducees had disappeared with the destruction of the Temple, long before the Tosefta was edited in the first third of the third century, Hillel is depicted not as a Pharisaic polemicist arguing with other sectarians, but as a champion of the people, a leader who advanced a populistic agenda and taught Torah to the masses. Hillel was, in effect, transformed into the first of the Patriarchs.

Despite the Toseftan editors’ attempt to recast this story to glorify Hillel, and by extension – the Patriarchal dynasty for generations to come, the original significance of this story must not be overlooked. The resolution of the controversy over offering the Passover Sacrifice on the Sabbath signified a major victory of the Pharisaic sages over the Sadduceean priests. As a result, from the days of Hillel until the destruction of the Temple 100 years later, the Sadducees indeed administered and carried out all of the manifold Temple rituals, but they were directed and supervised in many respects by their Pharisaic opponents. This shift was symbolized by the tradition that located the Pharisee-dominated Sanhedrin, High Court, in the lishkat ha-gazit, the office of the hewn chamber adjacent to the Temple precincts. On the 14th of Nisan that fell on a Sabbath, Hillel led a bloodless revolution in the Temple courtyard that conquered the Temple on behalf of his fellow Pharisaic sages, but, in a broader perspective, on behalf of the entire Jewish people.

[1] Translation is my own.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.