Zach Truboff

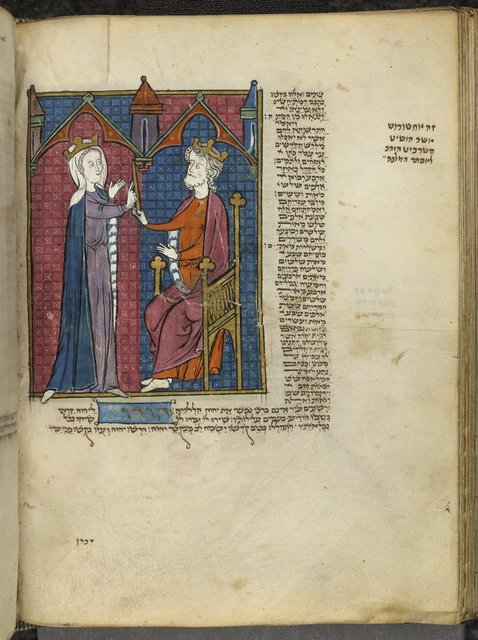

For most Jews, the story of Purim is best understood as a cautionary tale, one that reveals the dangers of a world without a Jewish State. Because the Jews of Persia live in exile, they are powerless and, therefore, vulnerable to both assimilation and genocidal anti-semitism. That they manage to survive Haman’s murderous decree is nothing less than a miracle, one that is made possible only by their willingness to fight for their lives. If there is a lesson to be learned from the holiday today, it is that Jews will only be safe when they are not under anyone’s boot. Some contemporary Zionists even go a step further and argue that the events of the Megillah take place after Jews were allowed to return to the Land of Israel, and therefore is to be read as a critique of those too comfortable and assimilated to make aliyah. Unsurprisingly, their fate nearly ends in doom.[1]

Zionism and the End of Exile

In large part, Zionism was invented to ensure that the events of the Megillah would never happen again, and few saw this more clearly than Theodor Herzl. With the existence of a Jewish State, he argued, the Jews of Eastern Europe would finally escape the Czar’s whip and be lifted out of poverty by a thriving economy in the Land of Israel. At the same time, the Jews of Western Europe could finally achieve a sense of national pride, which had long been denied them by anti-semitism in the countries in which they lived. While Herzl didn’t necessarily speak about an end to exile, his vision was unquestionably a call to end the problems that exile had imposed on the Jews, and that is why many Jews saw his call for a Jewish state in messianic terms. After hearing him at the first World Zionist Congress, Ahad Ha’am sensed that something in the Zionist project had changed. Before Herzl, Zionism had meant the slow, difficult work of encouraging Jews to move to the Land of Israel and strengthen Jewish settlement there, but now, Ahad Ha’am felt that this no longer satisfied them. Instead, they said: “What’s the good of this sort of work? The days of the messiah are near at hand, and we busy ourselves with trifles!”[2]

Political fantasies, especially utopian ones, are powerful things which can motivate people to make profound sacrifices, but they also can never quite live up to what they promise. In Ahad Ha’am’s eyes, Herzl’s depiction of a Jewish State could never come to be, not because the Jews couldn’t achieve a state, but because no state could live up to Herzl’s grand vision. Even if millions of Jews were to make aliyah, a Jewish State would be tiny when compared to others in the region, and it would exist on the most contested land in human history. Even with a strong army and robust economy, its dependence on more powerful states would be unavoidable. It risked being “tossed about like a ball between its powerful neighbors,” and to the extent it could survive, it would require “diplomatic shifts and continual truckling to the favored of fortune,” a condition Jews knew all too well from their centuries of exile.[3]

Small countries like Switzerland might be able to preserve a measure of neutrality, but this would not be an option for a Jewish State, Ahad Ha’am explains, for “they [the great powers] will all still keep an eye on it, and each power will try to influence its policy in a direction favorable to itself.”[4] If power is what Zionists are after, he cautioned, they will soon discover there is never quite enough of it, and they will inevitably find themselves “turning an envious and covetous eye on the armed force of our ‘powerful neighbors’.” For Ahad Ha’am, the trappings of sovereignty cannot guarantee much, and, in the end, they will always be lacking. A flag and an army may provide national pride and a measure of physical protection, but what the Jews would eventually discover is that life in a Jewish State can be tenuous, just as it was for their ancestors in Shushan.

The Illusions of Sovereignty

Fifty years later, as the nascent Jewish State was beginning to emerge, Ahad Ha’am’s assertions were confirmed by a surprising source, Rabbi Isaac HaLevi Herzog, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel and a leading Religious Zionist. He too understood that life under Jewish sovereignty would be more similar to Persia than many Zionists had imagined. In an important work intended to ground the future Jewish State in a halachic framework, Rabbi Herzog sought to address the status of religious minorities. If Muslims or Christians were to be considered idol worshippers according to halakhah, neither they nor their places of worship could be allowed to remain in the Land of Israel under Jewish sovereignty. Though he marshals a number of halachic sources to argue that Muslims and Christians need not be considered idol worshippers, in a moment of rare honesty, he admits that, even if they were, Israel would still have no choice but to allow them freedom of worship and protect their places of worship:

And now the time has come to look at the situation as it really is and examine the halakhah from the same realistic perspective. We have not conquered until now and could not conquer the land against the will of the United Nations according to their agreement. There is no doubt that until the coming of our righteous messiah, we will need their protection against a sea of political enemies that surround us, whose hand will also reach into the state, and there is no doubt that they will not give us the Jewish State unless the right of minorities to tolerance is established in the constitution and in the law.[5]

Though national sovereignty is often defined as the ability of a state to have total control over what takes place within its borders, Rabbi Herzog recognized that, in the modern world, no country is absolutely sovereign, least of all Israel, a state established and recognized through mechanisms of international law. Like Ahad Ha’am before him, Rabbi Herzog saw that there was a danger in imagining Jewish sovereignty to be more than it is. Though it can offer many things, it cannot allow Jews to act however they wish, even if they believe that is what the Torah demands of them. Any assertion to the contrary was a messianic fantasy.

Exile Returns…

That said, few contemporary Zionists would rush to agree with Ahad Ha’am and Rabbi Herzog, and would instead point to the many astounding accomplishments Israel has achieved since its founding. Is it not true, they might claim, that modern-day Israel has achieved so much of Herzl’s vision for a Jewish State? One regularly hears that Israel is a regional power with an economy that is the envy of the developed world. Despite being surrounded by vicious enemies, it has defeated nearly all its adversaries, showing the world that “Never Again” is not an empty slogan but an immutable fact made real by Jewish power. If anything, Israel’s successes have led many Zionists to feel it would be wrong for Israel to give in to international pressure, especially when it is so obviously fueled by anti-semitism. As a sovereign nation, Israel must decide what is in its best interest and act accordingly, regardless of what other countries might think, for this is the very promise of Zionism itself: the Jews and Jews alone are to be masters of their own destiny. Unlike their ancestors, Jews who read the Megillah today can breathe a sigh of relief knowing that the dangers it describes are no longer a threat, precisely because the Jewish people finally have a Jewish State.

At least, that was until October 7th. Suddenly, the events of the Megillah look all too familiar, especially for Jews in Israel. Hamas wears the mask of Amalek and seeks to “destroy, massacre, and exterminate all the Jews, young and old, children and women.”[6] If, in the past, Jews traditionally ate oznei Haman, also known as hamantaschen, to celebrate the defeat of their ancient enemy, today, bakeries around Israel are selling oznei Sinwar, expressing a similar sentiment. Even more striking has been the creeping awareness that even with a state of their own, Jews are not the masters of their own destiny, at least not in the way Zionists long imagined. Though most Israelis view eliminating Hamas as an act of obvious self-defense, one that shouldn’t need permission from others, the world sees it differently, in a way that is all too reminiscent of the Megillah. Though Haman’s genocidal plans were common knowledge throughout Persia, the Jews were unable to defend themselves without King Ahashveirosh’s approval, and only after a royal edict had been decreed could “the Jews of every city be permitted to assemble and fight for their lives.”[7] However, even though they had been given permission to fight, they could only do so for one day. If they needed more time they would be forced to go back to the king once more, without any guarantee that he would grant it.[8]

Jewish sovereignty promised Jews that they would finally have the power to defend themselves rather than be dependent on the whims of others, and yet, the current war has proven this to be far from the case. Despite the Israeli government’s protestations to the contrary, Ahad Ha’am’s concerns remain true. Recent months have made clear that in the face of Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran, Israel cannot survive without the assistance of larger, more powerful states like America and the political cover, funds, and armaments they provide. The Jews may be willing to fight, but there remain other, more powerful nations, to whom they must curry favor to guarantee their safety. Before October 7th, most Jews in Israel and the diaspora saw Purim as the quintessential story of what happens when the Jews are in exile, but now it seems that even Jews in Israel cannot escape it.

The Inescapability of Human Vulnerability

For many, this realization has been heartbreaking, but it has always been staring us in the face. According to Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, the Megillah is meant to teach us that all of human existence is vulnerable and no amount of power can solve this problem. To be alive in this world is to be exposed to threats far beyond our control that can strike at any time. This was the lesson learned by the Jews of Persia. By all measures, their life was good. They were welcome citizens of the empire, able to achieve high levels of status and success. Yet, without any warning, it was all proven to be transient when Haman’s decree proclaimed their destruction.

In the past, Jews understood the vulnerability of human existence, as it was at the heart of the Jewish experience of Exile. For Rabbi Soloveitchik, it is a “universal human condition,” something even sovereign states must confront, because “Danger always hovers over human beings as individuals and as political entities.”[9] It would be wrong, he explains, to think that it was limited to exile and that therefore a Jewish State could bring it to an end. The existence of Israel does not condemn the Megillah to the dustbin of history, he explains, but rather “applies to the state of Israel, its ministers, and military leaders, especially when the state is surrounded on all sides by cruel enemies.”[10] Zionism’s danger is that it causes Jews to think that their vulnerability can be eliminated. By doing so, it represses a religious truth we avoid at great risk. Pride goes before the fall, and the same is true with Jewish sovereignty. Writing in the wake of the Yom Kippur War, Rabbi Soloveitchik explains that:

“After the Six Day War, the government of Israel, and the top echelon of the military leadership in particular, lived for seven years in a mood of arrogance and forgot the principle of the vulnerability of man. That is why they thereafter found themselves in a very unpleasant situation to say the least.”[11]

Fifty years later, Israel finds itself once again in a similar position. Sovereignty can provide many things, but it cannot bring an end to the vulnerability Jews know so well from centuries of exile. Assuming otherwise leads only to disaster. Though Rabbi Soloveitchik’s words may sound harsh, they shouldn’t surprise us, for the Megillah itself makes this message clear. While Ahashveirosh, a king whose rule extends across the world, appears all-powerful, by the end of the story he is proven to be little better than a fool. He is defied by his wives and manipulated by those around him, and when his enemies plot to assassinate him, he is not saved by his military might or his intelligence services, but by a lone Jew, who happens to stumble upon the plot and chooses to save his life.

In achieving a measure of power and victory over one’s enemies, there is always a temptation to think that one’s situation has changed forever. Perhaps one was vulnerable in the past, and that will never be the case again. Yet, by the Megillah’s end, it is clear that Mordekhai and Esther knew better. When the Jews of Persia initially celebrate their victory over Haman on the 14th and 15th of Adar, they hold days of “feasting and merrymaking,”[12] but when Mordekhai and Esther later institutionalize the new holiday, they add an additional practice: giving gifts to the poor.[13] According to the commentary Melo Ha-Omer, this was done out of concern that in their euphoric celebrations, the Jews would mistakenly believe that with their victory over Haman, redemption was now at hand. As a result, charity would have been of no concern to them, because they would soon see a fulfillment of the Torah’s promise that “there shall be no needy among you.”[14]

However, Mordekhai and Esther “understood that the world had not yet been repaired such that the evil inclination was removed from the earth.” Therefore, they commanded that gifts to the poor should be given because “tzedekah is so great it brings redemption closer,” and because “[it] weakens the power of Satan, which draws its strength from the powers of impurity.”[15] Until the messiah finally arrives, all Jews live in a state of exile, and even the existence of a Jewish State cannot change that. Despite its many achievements, the needy have not disappeared, and evil persists all around us.

Who Has the Last Laugh?

This year, we have the opportunity to experience Purim in a different light, one in which we recognize that Jewish sovereignty is not all it is cracked up to be. For many Jews, this is a bitter pill to swallow, but that’s in part because Zionists aren’t known for their sense of humor. Here perhaps the teachings of Rabbi Nahman of Breslov can be helpful, for he reminds us that Zionism has always been something of a “joke.”

For Rabbi Nahman, life in the Land of Israel before the Jews went into exile was not that different from life in Persia, for even then God was not present in the way their ancestors had known. His tale, “The Humble King,” is intended to capture this by describing a land, meant to be Israel, with a mighty king, meant to be God. When a wise man comes from faraway to acquire the king’s picture, he discovers two strange facts about the land. None who live there have ever seen the king, and all the inhabitants constantly make fun of their kingdom, for even though the land aspires to justice and righteousness, corruption and lies are everywhere. The wise man is initially disturbed by this, but eventually makes his way to the palace. Though he is told that he cannot see the king, who hides behind a curtain, he is allowed to speak with him. At first, he reports to the king that his land is full of falsehood, immediately angering the king’s advisors, but then he appears to offer a joke, one that pleases the king. He tells him that despite what he has seen, he remains convinced that the king is righteous. Why? The reason he hides must be to distance himself from the wickedness of his kingdom!

In truth, Rabbi Nahman’s tale presents a world we know too well. A Jewish State may aspire to be a “light unto the nations,” but that claim will inevitably come into contradiction with the harshness of reality. Until the Messiah comes, it, along with the rest of the world, is filled with falsehood, and God appears absent even when the Jewish people most need Him. Yet, Rabbi Nahman reminds us that this need not get us down, and we may even find humor in it. He concludes his story with the verse “See Zion, the city of our gatherings (Hazeih Tziyon, kiryat mo’adeinu),”[16] and notes that when rearranged and put together, the first letter of each word spells metzaheik, which means to laugh.

Though the holiday of Purim is a perpetual reminder that Jewish power cannot guarantee the survival of the Jews or bring an end to exile, it also highlights the fact that exiled nations are supposed to disappear from history. Even though we can’t explain it, we are still here, and for more than two thousand years, with or without a state, we have celebrated a holiday that testifies to the miracle and absurdity of our survival. This year is no different. We just finally have an opportunity to be in on the joke.

[1] See Yonatan Grossman, Esther: Megillat Setarim (Jerusalem: Koren, 2013), 16-25. Also cited popularly by Ronen Shoval in “Ha-Tziyonut ha-Semuyah shel Megillat Esther,” Midah.

[2] From Ahad Ha’am’s 1897 essay “The Jewish State and the Jewish Problem” as cited in Arthur Hertzberg, The Zionist Idea (Doubleday Books, 1959), 262.

[3] Ibid., 268-269.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Rabbi Isaac HaLevi Herzog, Tehukah le-Yisrael al pi ha-Torah (Mossad HaRav Kook, 1989), 18-19.

[6] Esther 3:13.

[7] Esther 8:11.

[8] See Esther 9:13.

[9] Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Divrei Hashkafa (Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1992), 179-180.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Days of Deliverance: Essays on Purim and Hanukkah (New York: Ketav, 2007), 10.

[12] Esther 9:17.

[13] Esther 9:22.

[14] Devarim 15:4.

[15] Melo Ha-Omer on Esther 9:19. Melo Ha-Omer was composed by Rabbi Aryeh Leib ben Moses Zuenz (1768–1833).

[16] Isaiah 33:20. The story appears in Rabbi Nahman’s Sippurei Ma’asiyot.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.