Zach Truboff

Five months into the pregnancy, our twins were diagnosed with a rare disease.[1] Despite our best attempts to intervene and remedy the situation, the condition caused a host of complications. It eventually led to their premature delivery and deaths just a short time later. The weeks and months that followed were extraordinarily difficult. In the aftermath of tragic loss, one quickly discovers that despite attempts to move on, a reservoir of pain remains just underneath the surface. It doesn’t take much to breach the fragile barrier that holds grief at bay. Perhaps it is the sight of a newborn child or a family with young twins playing together. When the pain breaks through, it threatens to overwhelm and drag one beneath its depths. As I approached the first yizkor after their passing, my fear was that this too might become one of these moments. I did not want that to be the case. The last day of Pesah is a day of rejoicing and a day in which we dream of redemption. I was fearful it would become another moment when the world drains of its color and the weight of my loss nearly suffocates me.

Rabbinic commentators have long noted the incongruity of reciting yizkor on the festivals. If the mitzvah of simhat yom tov nullifies all public expressions of mourning, how is it possible that we can dedicate time on the festival to remembering our pain and loss? Various answers have been suggested[2], but I would like to propose the following: We recite yizkor on festivals in order to recognize that true joy must always live side by side with our loss. No matter how joyful we may be on the festivals, our pain cannot be erased, and attempting such emotional erasure would be nothing more than self-deception. Rather, experiencing authentic joy requires us to acknowledge our pain. The festivals inevitably force us to confront this reality, for what other time is there on the Jewish calendar that we yearn more to be with our loved ones?

This notion is beautifully expressed in a profound reading of the Song of the Sea offered by Avivah Zornberg[3]. Her essay, “Songline Through the Wilderness” helped shed light on my own experience and allowed for me to look at the Biblical narrative in a radically different fashion. The standard approach to the Song understands it to be an expression of unambiguous joy. When all hope appeared lost, when the Jewish people faced the dark waters in front of them and Pharaoh’s army at their backs, God miraculously split the sea and created a path for the Jewish people to walk forward. The Egyptians pursued them, only to perish as the ocean waves came crashing down upon them. After hundreds of years of slavery, the Jewish people finally witness the vanquishing of their oppressors. At this climactic moment (Exodus 14:31), “the Jewish people see the great hand that God inflicted upon the Egyptians, they are in awe of God, and they have faith in God and Moshe, His servant.” God has utterly proven Himself. Their tormentors had been punished. All of their pain and suffering had been washed away by the waters of the Red Sea. As slaves, all they could utter were unarticulated cries of misery, but now they are able to find the words to sing with pure faith and joy. That this interpretation is both beautiful and appealing is beyond question; We all yearn for the moments when we can finally let go of our pain and embrace only the good. This desire is at the heart of all our prayers for redemption and it is particularly appropriate for the end of Pesah.

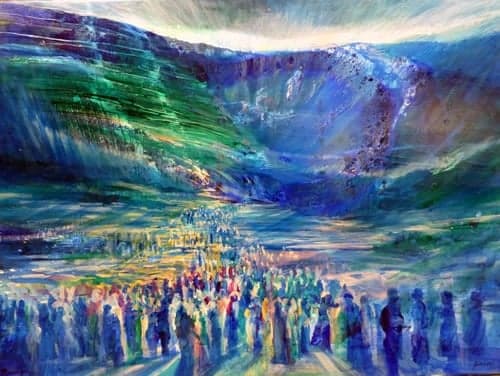

But there is another way to read this story. It is challenging, but better suited to the difficult reality of living in an unredeemed world. In her essay on the narrative, Zornberg cites the striking opinion of Rabbi Barukh ha-Levi Epstein, the nephew of the Netziv, who argues, that in fact, the Jewish people did not sing after having emerged victorious from the Red Sea. Instead, they sang while still marching through its waters pursued by Pharaoh’s army. If this is indeed the case, Avivah Zornberg points out, then the Song of the Sea cannot be understood as a song of pure joy and triumph, but rather as a song fraught with tension. The Jewish people must sing in full view of their oppressors. They must sing while their future is still uncertain, wondering whether they will indeed make it to the other side. The song does not deny their pain. Instead, they must find the strength to sing while still bearing the psychological wounds of slavery. Under these circumstances, the Song of the Sea must embody the complex reality of joy and pain living side by side. Until the final and complete redemption takes place, joy and pain have no choice but to co-exist. If this was true for Jewish people at the Red Sea, how much more so for us. Even on the festivals, days of rejoicing, we carry our losses with us. To deny our pains would be inhuman, and in doing so, we would fail to experience the true joy that we are called to feel on these days.

These themes are also evoked by the contemporary poet Christian Wiman in his startlingly powerful spiritual memoir, My Bright Abyss. The book chronicles his cancer diagnosis along with the slow and painful process of treatment. It captures his struggle to bring together the strands of faith that provided a lifeline for Wiman, and in doing so, it offers a meditation on what it means to live life when death stares one in the face. The author is keenly aware that even after recovery, the agony of such an experience leaves an indelible mark on us. He writes, (My Bright Abyss p. 19):

Sorrow is so woven through us, so much a part of our souls, or at least any understanding of our souls that we are able to attain, that every experience is dyed with its color. That is why even in moments of joy, part of that joy is the seams of ore that are our sorrow. They burn darkly and beautifully in the midst of joy, and they make joy the complete experience that it is. But they still burn.

When we recite yizkor, there is a part of our souls that burn. However, that doesn’t prevent us from singing. In fact, if we recognize that the Jewish people sang while still marching through the Red Sea, we come to understand another important truth: There are times when we sing not as a result of our joy but rather to serve as a lifeline that prevents us from drowning. In the same essay on the Song of the Sea, Zornberg quotes a teaching by Rebbe Nahman of Breslav[4], a religious thinker deeply familiar with the spiritually devastating impact of pain and loss. His writings are full of references to the presence of sadness and depression within the spiritual life. He understood, Zornberg writes, that

When one enters this wasteland a sense of worthlessness vitiates all capacity to live and to approach God. The objective facts may well be depressing; introspection may lead to a realistic sense of inadequacy and guilt. But this then generates a pathological paralysis, in which desire becomes impossible.

According to Rebbe Nahman, the only way to remove oneself from such a situation

is a kind of spiritual generosity- to oneself as well as to others. One should search in oneself for the one healthy spot, among the guilt and self-recrimination. This one spot, which remains recognizable, must exist. If one reclaims it, one then has a point of leverage for transforming one’s whole life.

This teaching is based on a verse from Psalms (37:10) “A little longer (V-od) and there will be no wicked man; you will look at where he was and he will be gone.” Instead of “a little longer” as in a moment of time, Rebbe Nachman reads this V-od as the one place where goodness and joy can still be found within us.

It is the role of song to help us find that one place, and then another. Once we are able to find one note, the power of song connects us to more and more. Zornberg further explains that through

[d]rawing those fragmentary, disjointed moments into connection with one another, one creates a song: a way of drawing a line through the wasteland and recovering more and more places of holiness.

In perhaps the most powerful words of the entire essay she notes that

[m]usic arises from joy, but the power of true singing comes from sadness. In every niggun there is the tension of the struggle between life and death, between falling and rising… the thin line of melody selects for goodness and beauty but it is given gravity by melancholy…

She concludes by observing that for Rebbe Nahman, “song opens the heart to prayer.” He cites another verse from Psalms, “I will sing to my God while I exist (be-odi)- “with my od, with that surviving pure consciousness of being alive.”

Rebbe Nahman’s teaching is an important lessons for Pesah, a holiday of song. During Pesah we sing Hallel. We sing at our seders. We read the Song of Songs and the Song of the Sea. All these different songs reflect the tremendous joy that is a fundamental part of the holiday. But, we should not forget that they are also songs of complexity through which we can also hear the harmony of pain and loss.

We lost our twins just days before Shabbat Shirah, the Sabbath of Song, when the Song of the Sea is read. At the time, I found comfort in a midrash that during the Song of the Sea, even the babies still inside their pregnant mothers raised their voices in song with the Jewish people.[5] It enabled me to realize that even in the short time that our twins were present in our lives, they too were part of the Jewish people. They contributed their voices if only briefly to the Divine symphony that we strive to sing. Rebbe Nahman teaches that even their absence is part of the song. Absence when consciously remembered creates its own unique form of presence, and if we listen closely, we can hear how even the absence of our loved ones adds to the harmony of the Jewish people.

Why is it that we recite yizkor on yom tov? On the one hand, we do it in order to acknowledge that our pain must have a seat at the table with our joy. But we are also permitted to allow ourselves to dream of a day when we will celebrate our holidays without yizkor. We dream of a day when our pain will be washed away and our scars will finally heal. We dream of redemption, a dream deeply appropriate for the last day of Pesah. We dream of the day when we will gather with all our loved ones, those both present and absent, in order to recite the words from the seder. As it says in the Haggadah, we will sing in order “to thank, praise, pay tribute, glorify, exalt, honor, bless, extol, and acclaim God who has performed all these miracles for our fathers and for us. He has brought us forth from slavery to freedom, from grief to joy, from mourning to joy , from darkness to great light, and from subjugation to redemption.” On that day we will finally set aside our pain and loss to recite a new song before God, Halleluyah.

[1] This essay was originally delivered as a yizkor sermon on the last day of Pesah. It took place just a few months after the loss of our twin boys, who had been born extremely premature and failed to survive.

[2] For example, according to the Levush (Orah Hayyim 490) yizkor is recited on the last day of yom tov because the torah reading for that day is “kol ha-bechor.” This sections includes a call for those making aliyah l-regel to bring an offering or gift of some kind, which was later interpreted as an injunction to give tzedakah. From this developed the practice to make a pledge for tzedakah on the last day of the festival which would often be done in the memory of a loved one.

[3] Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg, “Songline Through the Wilderness,” in The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus (New York: Schocken Books, 2001).

[4] Likkutei Moharan 282.

[5] Sotah 30b.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.