Akiva Mattenson

U-netaneh Tokef, one of the most memorable pieces of the Rosh Hashanah liturgy, imagines the central drama of the day as a trial in which humanity is called to account before God, as the angels in the divine retinue declare, this day is “the day of judgment” [yom ha-din]. Often when we reflect on the significance of Rosh Hashanah as a day of judgment, we consider what it will mean for us to be judged: we engage in protracted self-reflection and a sober consideration of our shameful misdeeds. We try to embody sincere remorse and attempt to turn toward a path of righteousness. Our attention is focused on the tragedy of human sinfulness and the redemptive possibility of repentance [teshuvah].

Less often do we consider what it will mean for God to judge us. Yet, thinking through God’s relationship with judgment may fruitfully complicate our picture of Rosh Hashanah as a cosmic trial of humanity. What’s more, attending to God’s part in the drama of judgment may be valuable in achieving a different understanding of the ritual fabric of the day. To engage in this theological work, we will turn to the corpus of rabbinic literature and consider the striking ways in which our sages imagined God’s relationship with judgment.

God’s Distinctive Strength: The Quality of Compassion

We should begin by noting the following: for the sages, God’s strength, prowess, and power is most on display not in acts of stern judgment but in acts of tender compassion. This idea is explored in a moving midrash from the Sifre on Numbers. The textual locus for this midrash is the verses in Numbers in which Moses is told to gaze out over the land of Israel before meeting his end at its border. Drawing on the parallel account found in the book of Deuteronomy, the sages direct our attention to the impassioned plea for entrance into the land offered by Moses at this juncture:

And I pleaded with YHVH at that time, saying, ‘My Master, YHVH, You Yourself have begun to show Your servant Your greatness and Your powerful hand, for what god is there in the heavens and on the earth who could do like Your deeds and like Your might? Let me, pray, cross over that I may see the goodly land which is across the Jordan, this goodly high country and the Lebanon. (Deuteronomy 3:24–25)

In the course of his plea, Moses recollects God’s great and unparalleled strength, which God has only begun to reveal. A plain-sense reading of these verses would understand the strength in question as something like physical might and dominance – the kind of physical might and dominance that was on display in God’s liberation of Israel from Egypt. Indeed, throughout the book of Deuteronomy the “powerful hand” [yadkha ha-hazakah] of God is tied to the moment of the exodus and the miraculous, thundering power with which God punished the Egyptians and saved Israel. This point also helps make sense of the connection between Moses’s reference to God’s strength and his prayer for entrance into the land: He has only just begun to bear witness to God’s might and strength through the punishment of Egypt and the conquest of the lands east of the Jordan. Thus, he prays for the allowance to see more of this might and strength as the people enter the land and conquer its inhabitants with the aid of God’s strong arm.

Yet for the sages, the strength at stake in this passage is not that of overpowering might but overpowering compassion manifested in forgiveness and generosity. The midrash reads as follows:

Another interpretation: You have begun [hahilota] (Deuteronomy 3:24) – You have profaned [hehaltah] the vow. You wrote in the Torah, Whoever sacrifices to a god [other than YHVH alone shall be proscribed] (Exodus 22:19), and your children worshipped foreign worship, and I requested for them compassion and you forgave – You have broken the vow.

Your greatness (Deuteronomy 3:24) – this is the quality of your goodness, as it is said, And now, let the strength of my lord be great (Numbers 14:17).

And your hand (Deuteronomy 3:24) – this is your right hand, which is extended to all those who come through the world, as it is said, your right hand, YHVH, glorious in strength (Exodus 15:6), and it says, but your right hand, your arm, and the glow of your face (Psalms 44:4), and it says, By Myself have I sworn, from My mouth has issued righteousness [tzedakah], a word that shall not turn back (Isaiah 45:23).

The powerful (Deuteronomy 3:24) – For you subdue [kovesh] with compassion your quality of judgment, as it is said, Who is a God like You, forgiving iniquity and remitting transgression (Micah 7:18), and it says, He will return, he will have compassion on us, he will subdue [yikhbosh] our sins, You will keep faith with Jacob (Micah 7:19–20).

For what god is there in the heavens and on the earth (Deuteronomy 3:24) – For unlike the way of flesh and blood is the way of the Omnipresent. The way of flesh and blood: the one greater than his friend nullifies the decree of his friend, but you – who can withhold you [from doing as you please]? And so it says, He is one, who can hold him back? (Job 23:13). R. Yehudah b. Bava says: A parable – to one who has been consigned to the documents of the kingdom. Even were he to give a lot of money, it cannot be overturned. But you say, “Do teshuvah, and I will accept [it/you], as it is said, I wipe away your sins like a cloud, your transgressions like mist (Isaiah 44:22).

The text begins with a playful revocalization of Moses’s opening words that transforms “You have begun [hahilota]” into “You have broken [hehalta] the vow.” In so doing, the sages shift our attention from the scene of the exodus suggested by the plain sense of the verses to the scene of the golden calf, in which God broke His vow to punish those who worship other gods. In that moment of Israel’s profound failure, God’s strength manifested itself not through physical might but through forgiveness and compassion. What’s more, in speaking of God breaking the vow, the text implicitly rejects another pervasive conception of divine power and strength – namely, that divine power rests in stern and difficult judgment. It is not uncommon to hear compassion and forgiveness referred to as a kind of feebleness in contrast to the strength at work in administering justice even when it is difficult or tragic. The sages carefully avoid such a perspective and assert that divine strength lies not in holding to a vow even when it is challenging but in breaking a vow for the sake of compassion and forgiveness.

The themes introduced in this first part of the midrash are explored as the midrash continues. First, God’s greatness is translated into God’s goodness through the invocation of a verse tied to another scene of divine forgiveness and compassion – namely, the scene in the aftermath of the sin of the spies. Second, the hand of God, rather than extended against the enemies of Israel in a gesture of physical might is extended in a gesture of compassionate generosity. Indeed, verses tying the hand of God to the destruction and conquest of Egypt and other nations are reread in light of this rabbinic commitment to rendering divine strength as compassion. Third, God’s power is understood as His compassion overcoming and subduing His quality of judgment. In the final piece of the midrash, we are reminded that God, unlike earthly kings, can break vows and overturn decrees in displays of compassionate forgiveness. Furthermore, when God does vow, it is to bind Himself in commitment to the kindness of tzedakah, as noted in the verse from Isaiah quoted by the midrash: “By Myself have I sworn, from My mouth has issued righteousness [tzedakah], a word that shall not turn back” (Isaiah 45:23). There is none who can withhold or nullify His decrees of compassion, generosity, forgiveness, and kindness.

God, Anger, and Judgment: The Divine Struggle to be Compassionate

Thus, what constitutes divine strength, what makes God unique and incomparable, is a capacity for compassion. This compassion sits in an uncomfortable tension with the rage that lights God against the enemies of Israel and the stern judgment that calls for unmitigated punishment. Yet it is precisely this tension that marks divine compassion as a strength. For it is only in mightily subduing a predilection for unmitigated judgment that God’s compassion emerges victorious. This is the meaning of the striking phrase found in our midrash, “For you subdue [kovesh] with compassion your quality of judgment.” There is struggle and conquest involved in the victory of compassion over divine judgment. The phrase calls to mind a teaching found in Mishnah Avot 4:1: “Ben Zoma says… Who is mighty? The one who subdues [kovesh] his impulse, as it is said, one slow to anger is better than a mighty person and one who rules his spirit than the conqueror of a city (Proverbs 15:16).” Just as human might emerges in the difficult and effortful conquest of our impulse toward wickedness, divine might emerges in the difficult and effortful conquest of God’s impulse toward judgment and anger.

This notion that God is locked in a fierce struggle with His tendency toward judgment and anger and is striving mightily to act compassionately with His creatures comes to the fore in a beautiful text from Berakhot 7a:

R. Yoḥanan said in the name of R. Yosi: From where [do we know] that the Holy Blessed One prays? As it is said, I will bring them to the mount of my sacredness, and let them rejoice in the house of my prayer (Isaiah 56:7) – ‘their prayer’ is not said, rather my prayer. From here [we know] that the Holy Blessed One prays. What does he pray? R. Zutra b. Tuviah said that Rav said: May it be my will that my compassion subdue my anger, and my compassion prevail over my [other] qualities, and I will behave with my children with my quality of compassion, and I will enter before them short of the line of the law.

Critically, God’s will for compassion rather than anger or judgment is couched in the language of prayer. To pray for something is in some ways to admit that achieving that something lies beyond the ken of one’s intentional capabilities. There is a measure of hope in prayer that signals a desire that may go unfulfilled. In this case, God’s prayer for compassion signals the degree to which victory against judgment and anger is not a forgone conclusion and the prevailing of compassion is something that will require effort and struggle.

This struggle is powerfully dramatized by the sages in a number of texts that reimagine God’s anger and judgment as independent personified characters. The retributive aspects of God’s nature become angels who can preclude Him from enacting His will and are often at cross-purposes with this compassionate God. Thus, in the case of divine anger we encounter the following passage from Yerushalmi Ta’anit 2:1:

R. Levi said: What is the meaning of erekh ‘apayim? Distancing anger. [This is compared] to a king who had two tough legions. The king said, “If [the legions] dwell with me in the province, when the citizens of the province anger me, [the legions] will make a stand against [the citizens]. Instead, I will send them off a ways away so that if the citizens of the province anger me, before I have a chance to send after [the legions], the citizens of the province will appease me and I will accept their appeasement.” Similarly, the Holy Blessed One said, “Af and Hemah are angels of devastation. I will send them a ways away so that if Israel angers me, before I have chance to send for them and bring them, Israel will do teshuvah and I will accept their teshuvah.” This is that which is written, They come from a distant land, from the edge of the sky [YHVH and the weapons of his wrath–to ravage all the earth] (Isaiah 13:5). R. Yitzḥak said: And what’s more, he locked the door on them. This is that which is written, YHVH has opened his armory and brought out the weapons of his wrath (Jeremiah 50:25) …

Af and hemah, terms often used in the Bible to describe God’s anger, are here transformed into “angels of devastation” that operate almost independently of God. In the mashal, they are compared to two military legions who would loose devastation on the citizenry at the slightest sign of the king’s anger. It appears almost as though the king would be unable to hold them back from their rampage once they set forth against the people. This frightening independence is confirmed in the nimshal, wherein God sees a need not only to send them far away but also to lock them up. If they are allowed to roam free, who knows what havoc they might wreak. One senses in this text the precariousness of God’s relationship with anger and wrath. At the same time, the sages make clear the profound efforts God makes to favor compassion and forgiveness.

Middat hadin, or “the quality of judgment,” also becomes an autonomous character in the rabbinic imagination. Thus, in Pesahim 119a we read:

R. Kahana in the name of R. Yishma’el b. R. Yose said that R. Shim’on b. Lakish in the name of R. Yehudah Nesi’ah said: What is the meaning of that which is written, and they had the hands of a man under their wings (Ezekiel 1:8)? ‘His hand’ is written. This is the hand of the Holy Blessed One that is spread under the wings of the Ḥayyot [i.e. angels] in order to accept those who do teshuvah from the grips of middat hadin.

In this dramatic scene, God spreads His hand beneath the wings of the angels so as to collect up the remorseful and repentant and protect them from falling into the hands of the less than sympathetic middat hadin. One is given to imagine that were these people to fall into the grips of middat hadin, God would be powerless to retrieve them or at the very least would need to valiantly struggle for their release. In the cosmic drama, middat hadin is God’s adversary, attempting to uphold the strict letter of judgment while God vies for the victory of compassion and forgiveness. The sages make this point clear in several texts that situate this struggle at various moments in our mythic-history. Thus, we are told that God constructed a sort of tunnel in the firmament so as to sneak Menasheh – the repentant wicked king of Yehudah – past middat hadin, who would surely have prevented his acceptance in heaven (Sanhedrin 103a). Similarly, when creating humankind, God disclosed to the ministering angels only that righteous people would emerge from Adam. God chose to conceal the future reality of wicked people, precisely because He was certain that had middat hadin known, it would have prevented the creation of humanity (Bereishit Rabbah 8:4). Middat hadin was also critical in delaying and precluding the exodus from Egypt. Witnessing the utter depravity of captive Israel who had adopted the customs and practices of the Egyptians, middat hadin could not allow for their liberation. Only on the strength of God’s prior commitment and oath to redeem Israel was God able to defeat the uncompromising will of middat hadin (Vayikra Rabbah 23:2).

These texts are theologically audacious and undoubtedly jarring to ears accustomed to the staid contours of a Maimonidean God. God is a vulnerable, struggling God, fearful of the most dangerous and powerful members of the divine family – anger and judgment – and intent on defeating them through precautionary measures, wily maneuvers, and whatever resources are available. As we briefly alluded to earlier, this picture departs in certain ways from that painted by Sifre Bemidbar and Berakhot. In those texts, the struggle for compassion is rendered internal to God’s person. Judgment and anger and compassion compete for attention in the divine psyche and God struggles mightily for the victory of His more compassionate side. Here, by contrast, judgment and anger are reified and externalized as members of the angelic retinue. It is worth pausing to consider how this impacts the drama. In externalizing anger and judgment, God is rendered wholly and incorruptibly compassionate rather than divided against Himself. This constitutes a certain sacrifice in divine psychological complexity. However, this sacrifice allows for richer imaginative possibilities when it comes to considering how God fights against judgment and anger for the victory of compassion – bolting the door against them, concealing facts from them, tunneling beneath them, etc. I don’t wish to advocate for one of these images to the exclusion of the other. Each of these images captures something about the character of God’s struggle with judgment and anger, and it will only be through the cumulative effect of seeing this struggle in multiple successive perspectives that we will appreciate its full-bodied richness.

“The Day of Judgment”? A Reconsideration

With this consideration of God’s relationship to judgment in mind, we can now turn to consider the day of Rosh Hashanah and how it fits into this broader narrative. In Vayikra Rabbah 29:3, we encounter the following passage:

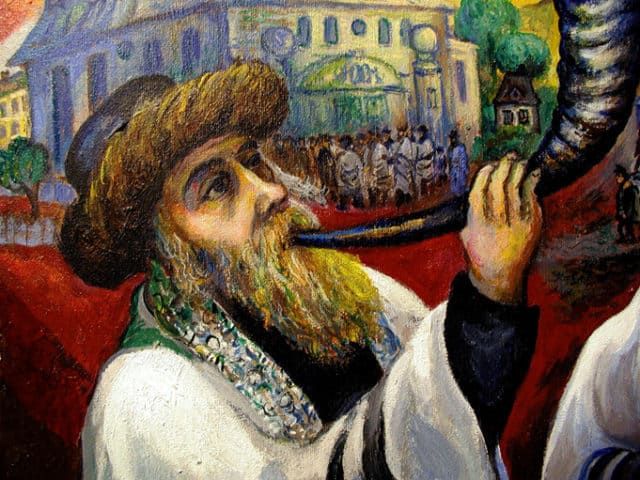

Yehudah b. Naḥmani in the name of R. Shim’on b. Laqish opened: God ascends amidst acclamation [teru’ah]; YHVH, to the blasts of the shofar (Psalms 47:6). When the Holy Blessed One ascends to sit on the throne of judgement on Rosh Hashanah, he ascends for judgement. This is that which is written, God [Elohim] ascends amidst acclamation [teru’ah]. And once Israel take their shofarot and blow them, immediately YHVH, to the blasts of the shofar. What does the Holy Blessed One do? He rises from the throne of judgement and sits on the throne of compassion, and is filled with compassion for them and transforms the quality of justice into the quality of compassion for them. When? On Rosh Hashanah, in the seventh month on the first of the month.

In the rabbinic imagination, the names of God are to be associated with distinctive traits (see for example, Sifre Devarim 26). Thus, Elohim signifies God’s quality of judgment while YHVH signifies God’s quality of compassion. Capitalizing on this rabbinic trope, our midrash imagines the shift in divine epithets found in the Psalmic verse to signify a shift in God’s character on the day of Rosh Hashanah. While God initially ascends the throne of judgment, the blasts of the shofar sounded by Israel move God to abandon the seat of judgment for that of compassion. This idea is one worth examining more closely.

First, this text might push us to reconsider the aptness of yom ha-din or “the day of judgment” as a name for Rosh Hashanah. If we take this text seriously, the day is less one of judgment and more one of the abandonment of judgment for the sake of compassion. It is part and parcel of the story of God’s struggle against the potent force of strict judgment. The day is one on which the singular strength of God is on display, as God succeeds in conquering and subduing God’s quality of judgment with compassion. In a certain sense, we might even take the commandment issued by God for Israel to sound the shofar on Rosh Hashanah as a prophylactic measure against middat hadin. God knows that the sound of the shofar’s blast will move Him to remember His deepest commitments, His truest self, and His love and compassion for Israel. For this reason, God assigns this tasks to Israel on the day He has set aside for judgment.

If we wish to deepen our appreciation of Vayikra Rabbah’s claim, we might turn to Maimonides’ articulation of the purpose of the shofar. In Hilkhot Teshuvah 3:4, Maimonides writes as follows:

Even though the sounding the shofar on Rosh Hashanah is a decree of the text, there is a hint for it. That is to say, “Wake up, sleepers, from your sleep and comatose from your comas, and return in teshuvah and remember your creator. Those who forget the truth through time’s hollow things and wile away all their years with hollowness and emptiness that won’t be of use and won’t save, look to your souls and improve your ways and your deeds. And each one of you, abandon his wicked way and his thoughts, which are not good.”

For Maimonides, the shofar is a piercing cry that wakes us from our slumbering attitude. In a world where we find ourselves forgetful of what is important, the sound of the shofar shocks us back into an awareness of our deepest commitments and moves us to abandon the hollow and useless things in life in favor of righteousness. In R. Yitzhak Hutner’s rendering of this idea, “the shofar can bring to life the traces and transform something’s trace or impression into its embodied fullness” (Pahad Yitzhak, Rosh Hashanah 20). For both Maimonides and R. Hutner, hearing the shofar is an activity designed for the benefit of human beings. However for Vayikra Rabbah, it would seem that hearing the shofar is something that also benefits God. If the shofar has the capacity to wake us from our slumber and restore vitality to our sedimented commitments, perhaps it has the same capacity to do so for God. Parallel to Maimonides’ “Wake up, sleepers” might be the Psalmist’s cry: “Rise, why do you sleep, lord?” (Psalms 44:24). God calls on us to sound the shofar to wake Him from His slumber and transform the trace of reserve compassion into its embodied fullness.

The Sound of the Shofar and the Tragic Costs of Judgment

But what is it about the sound of the shofar that so moves God to abandon judgment and return to His deep and fundamental commitment to compassion and forgiveness? We might find the beginnings of an answer through reflecting on the story of the binding of Isaac and its aftermath, a story we in fact read on the second day of Rosh Hashanah. In considering what motivated God to test Abraham with the sacrifice of his child, the late midrashic collection, Yalkut Shim’oni, imagines the following:

Another interpretation: [This is compared] to a king who had a beloved [friend] who was poor. The king said to him, “It is on me to make you wealthy,” and he gave him money with which to do business. After a time, he [i.e. the poor friend] entered the palace. They said, “For what reason is this one entering?” The king said to them, “Because he is my faithful beloved [friend].” They said to him, “If so, tell him to return your money.” Immediately, the king said to him, “Return to me that which I gave you.” He did not withhold, and the members of the palace were embarrassed, and the king swore to grant him more wealth. The Holy Blessed One said to the ministering angels, “Had I listened to you when you said, what is a human being, that you are mindful of him (Psalms 8:5), could there have been Abraham, who glorifies me in my world?!” Middat ha-din said before the Holy Blessed One, “all of the trials with which you tested him involved his money and property. Try him through his body.” He said to him, “He should sacrifice his son before you.” Immediately, “He [i.e. God] said to him [i.e. Abraham], take your son (Genesis 22:2). (Yalkut Shim’oni, Vayera)

In the eyes of this midrash, God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice Isaac was issued at the prodding of middat ha-din. Skeptical of the fortitude and authenticity of Abraham’s commitment to God, middat ha-din asks God to truly test Abraham through his flesh and blood rather than through his material possessions by asking him to sacrifice his son. The story of the binding of Isaac is thus cast as a concession of God to the skepticism of middat ha-din, the quality of judgment. Unobscured by the love God feels toward Abraham, middat ha-din coldly assesses the situation and desires a strict test of Abraham’s righteousness.

This midrash is particularly striking as it evokes and plays with another narrative found in the Biblical canon – namely, the story of God’s test of Job (Job 1–2). In the beginning of the book of Job, God boasts of Job’s righteousness, prompting the Adversary or ‘ha-satan’ to question the authenticity of Job’s commitment. Like the attendants to the king in the mashal of our passage, the Adversary suggests that robbing Job of the material wealth God has showered upon him will test the strength of Job’s piety. When this fails, the Adversary responds by discounting the previous test as insufficient. A true test of Job’s piety will come when his body and flesh are inflicted rather than merely his wealth. This again is echoed in the comments of middat ha-din, who insists God try Abraham “through his body” [be-gufo]. The implication of this parallel is hard to ignore. By drawing on the narrative framework of the book of Job, the midrash in Yalkut Shim’oni casts middat ha-din in the role of satanic adversary to God. This text would then continue the trend we have seen of depicting middat ha-din in a tense and difficult struggle with God. Yet remarkably, if middat ha-din is the satanic adversary to God, then its suggestion of binding Isaac to the altar would seem to emerge in a strikingly negative light.

What then is the source of this ambivalence about testing Abraham through the sacrifice of his son? And what does all of this have to do with the sound of the shofar? One possible answer emerges from a midrash that first appears in Vayikra Rabbah 20:2:

He took Isaac his son and led him up mountains and down hills. He took him up on one of the mountains, built an altar, arranged the wood, prepared the altar pile, and took the knife to slay him. Had [God] not called upon him from the heavens and said, Do not reach out your hand (Genesis 22:12), Isaac would have already been slain. Know that this is so, for Isaac returned to his mother and she said to him, “Where have you been, my son?” And he said to her, “My father took me and led me up mountains and down hills.” And she said, “Woe for the son of a hapless woman! Had it not been for an angel from the heavens, you would have already been slain!” He said to her, “Yes.” At that moment, she uttered six cries, corresponding to the six blasts of the shofar. They said, “she had scarcely finished speaking when she died.” This is that which is written, And Abraham came to mourn for Sarah, and to weep for her (Genesis 23:2). Where did he come from? R. Yehudah b. R. Simon said: He came from Mount Moriah.

For this midrash, the binding of Isaac to the altar and his near-sacrifice had tragic consequences in the form of the death of his mother, Sarah. What’s more, this midrash explicitly ties the pained cries of Sarah to the piercing sound of the shofar. If we consider this text together with our passage from Yalkut Shim’oni, what emerges is a searing indictment of middat ha-din. Strict judgment leaves casualties of pain, tragedy, and death in its wake, and it is for this reason that it should be seen as an unsympathetic, almost satanic adversary to which God sadly succumbed in asking Abraham to sacrifice his son. When administering strict judgment, one may become so myopically focused on the subject at hand that the unintended and violent consequences of rendering a certain verdict go unnoticed. Middat ha-din fails to note the mothers who suffer pangs of sorrow at the loss of children taken in the name of judgment and justice. Sounding the shofar recalls God to the moment of Sarah’s tragic death and awakens God to the reality of middat ha-din’s violence and its many casualties. God cannot help but return to Himself, to His deepest commitments, and subdue the impulse toward judgment in the calming waters of compassion and forgiveness.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.