Josh Cahan

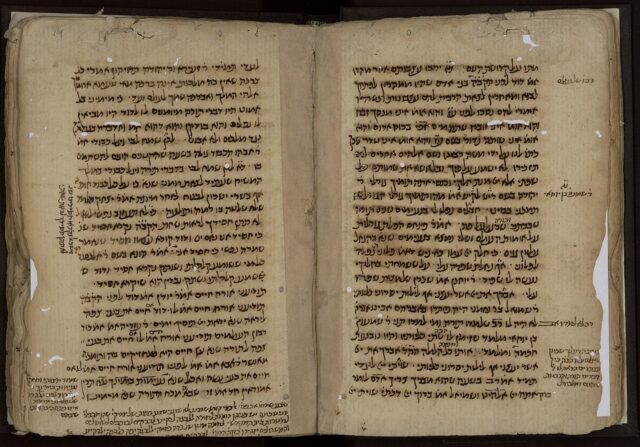

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 12:11

R. Lazar said: Like a king who wished to marry a well-born noblewoman, and said, “I will not wed her without wooing her. I will give her gifts and only then wed her.” He saw her at the baker and filled her arms with loaves; at the tavern, he gave her spiced wine; at the butcher, he gave her fowl; at another, he gave her choice meats; at another, dried figs. At the baker he filled her arms with loaves: “Behold, I will rain upon you bread from the heaven.” (Id. 16:4). At the tavern, he gave her spiced wine: “Then Israel sang this song: Spring up, O well—sing to it.” (Bamidbar 21:17). At the butcher, he gave her fowl: “And God swept quail from the sea.” (Id. 11:31) At another, he gave her dried figs: “God fed them honey from the rock” (Deuteronomy 32:13).

The moment of revelation is a hugely symbolic event, a unique moment of direct divine-human encounter, and the episode that sets the tone, and thus the very nature, of the relationship between God and Israel going forward far into the future. Shifts in how Jews have understood the nature of God’s presence in the world have therefore often led to new interpretations of that first encounter, encoding changing ideas about what God asks and expects of us and how we, in turn, should seek connection with God.

We are familiar with the move from the revelation of the biblical God—full of sound, fury, and real danger—to the rabbinic picture, where Torah is more of a compact in which God and Israel are both participants. In the rabbinic narrative, God exchanges a position of control and dominance for one of expectation and hope, pleading with Israel to engage with God and God’s Torah, even participating actively in their debates about it. The rabbis want and need to see God more as a partner in achieving a Torah-infused world than as a ruler insisting upon it.[1]

Nonetheless, the expectations that God has of us are, by and large, impossibly high. God does, at least in some texts, invite, rather than force us, to accept Torah. But in so doing, God seeks a full partner, one who commits to studying and observing that law in its entirety. God gives us God’s precious Torah with the understanding that we will immerse ourselves in it, that we will embrace it, and through it embrace God, fully and deeply. God may not have given the Torah to angels, but this version was certainly meant only for sages.

A strikingly different picture is painted in the early midrashic collection Pesikta De-Rav Kahana, one that is almost shockingly subversive. The distant, commanding deity is replaced by a doting father, a nervous suitor seeking to win Israel’s favor. The weeks before Israel arrives at Sinai are a time of rest, of courtship. The Midrash sees in revelation the story not of God allowing Israel a glimpse of the Divine, but of actively seeking out and yearning for relationship. It invites its readers—and us—to hear a different kind of divine call.[2]

A brief word of context about Midrash Aggadah in general and the Pesikta in particular. Midrash Aggadah is often grouped together with Mishnah and Talmud under the name “Rabbinic Literature,” but it is in fact a separate body of writing. It is quite distinct in style and concerns from the network of earlier rabbinic texts, sometimes surprisingly so. And though it presumably emerges from the same circles that produced other rabbinic texts, it mostly quotes a different set of sages.

There is one other noteworthy fact about Midrash Aggadah for our purposes. The other main text composed in the Land of Israel in the Amoraic Period was the Talmud Yerushalmi, which reached its final form around the year 400 CE. After decades of searching for evidence that there was some later, expanded version that was not preserved, scholars have concluded that work on the Yerushalmi stopped for good at that point, and they often regard this as representing the end of the creative work of these sages. But the earliest collections of Midrash Aggadah date to the fifth and sixth centuries CE, meaning that Palestinian sages did not stop composing, but rather shifted their focus to a new type of literature. The theological and cultural gap between Talmud and Midrash Aggadah therefore appears to represent not simply two different strands of rabbinic thought but an intentional shift in focus and ideology, a move to engage with and present Torah in a new way.

It turns out that the era of Midrash Aggadah, the fifth and sixth centuries, coincides precisely with a major shift in the role of rabbis in the Palestinian Jewish community. It is at this time that we see an explosion of synagogue construction, with the rabbis emerging from their mainly cloistered place in the academy to take on active leadership roles.[3] This may have been a time of hardship for the Jewish community, but it was far from one of dormancy. It was, instead, a period in which Jewish cultural life flourished like never before, and when Jews who had long paid rabbinic traditions scant attention now turned to the rabbis for guidance. And thus we find the rabbis, speaking with Midrash to a very different audience than they did with Talmud, having to ask, in a newly urgent way, how Torah might speak to the common people.

The Pesikta, in a moment of unusual self-awareness, describes this very shift:

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 12:3

“For I am faint with love” (Shir Ha-Shirim 2:5). R. Yitzhak said: In earlier times, when money was sufficient, people would come to study words of Mishnah and Talmud. Now that money is not sufficient, and moreover we are oppressed by occupiers, people yearn to hear comforting words of Bible and aggadah.

The passage uses Shir Ha-Shirim 2:5 to frame the sweetness of the Torah that God is preparing to give Israel: “Sustain me with raisin cakes, refresh me with apples, for I am faint with love.” On the last phrase, R. Yitzhak draws a stark contrast between the work of teaching Torah in “earlier times” as compared to his own. In those earlier times, when the Jews’ situation was easier, people came to rabbis wanting to delve into the complexity of legal texts and reasoning. The present, though, is a time of poverty and oppression, in which people are yearning for the simple, comforting, affirming messages of aggadah.

On one level, this serves as an explanation of the shift noted above, where the rabbis at a certain point stopped developing and expanding Talmud and instead turned their creative efforts to composing Midrash Aggadah, which is indeed exclusively nonlegal and largely focuses on broad ethical and spiritual themes. It also very likely gives us at least one clue about the impetus for the growth of synagogues in this period. R. Yitzhak suggests that this was a period of economic and social hardship for the community, and people turned in large numbers to synagogues, and to rabbis as representatives of the tradition, for words of support and affirmation.

This does necessitate one emendation to R. Yitzhak’s claim: it would seem that the people coming to the rabbis to learn aggadah are not the same people who once sought Mishnah and Talmud. The rabbis were suddenly addressing a much wider audience, one with far less learning than the students who once came to be pupils. And thus, we arrive at the real significance of the move from Talmud to Midrash: it reflects the challenge of addressing a very different audience, of exploring how Torah could speak directly to the needs and the hearts of ordinary Jews.

Let us look at one example of how the Pesikta frames the lead up to the great encounter of revelation:

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 12:11

“In the third month” (Exodus 19:1). The third month has come! Like a king who betrothed a noblewoman and set a wedding date. When the date arrived, they announced, “It is the hour when she enters the huppah!” So too, when it came time for Torah to be given, they said, “It is the hour for Torah to be given to Israel!”

The metaphor of Sinai as a wedding between God and Israel is a well-known one, tracing back at least to the Mishnah if not earlier.[4] But several features of this passage stand out. One is that here, and throughout the Pesikta, Israel is depicted not just as a bride but specifically as a noblewoman or one of high birth. This elevates the status and importance of Israel, and it also means that this wedding is important and a good match for the groom as much as for the bride. Here, the groom is the one who sets the date, and then waits in a state of nervous anticipation, until at long last his herald announces that the awaited day has arrived. There can be no question of God changing God’s mind, or of Israel proving inadequate, because God is portrayed as the one who has waited for and anticipated this match.

The end of that section takes this image even further.

R. Abba bar Yudan said: Like a king marrying off his daughter. He had made a decree in the empire that those from Rome may not go down to Syria, and those from Syria may not go up to Rome. But when he wishes to marry off his daughter, he sets aside the decree. So too, before the Torah was given, “the Heavens are God’s domain, and the Earth was given to humans” (Psalm 115:16). But when Torah was given from the Heavens, “Moshe went up to God” (Exodus 19:3), and “God came down onto Mt. Sinai” (ibid. 19:20).

Here the roles have shifted: the Torah is the bride that is being married off to Israel, now in the role of groom. But consider the pathos of this claim. The king so deeply desires to marry his daughter to a particular suitor that he sets aside his own decree to allow it. And that decree, it turns out, is the very separation of heaven and earth, a decree that has defined God’s relationship to the world. Now, the idea that the moment of Matan Torah represented an abrogation of the natural order, the crossing of an otherwise impermeable boundary, can be found in earlier rabbinic sources. But it is usually presented as a great—and in some tellings undeserved—kindness of God to allow us this taste of heaven. In this version, it is God who is bending God’s own rules for the universe in order to unite God’s beloved Torah with its proper stewards, Israel. God so deeply desires this union that God literally moves heaven and earth to make it possible.

But it is in its revisionist accounts of the events between departing from Egypt and arriving at Sinai, recounted in Exodus 15-17, that the Pesikta truly stands out. The Israelites arrive at Sinai ba-hodesh ha-shelishi, in the third month, understood by the rabbis as the first day of that month, six weeks after leaving Egypt. This time is marked by a series of crises. The Israelites rise up in protest over the lack of drinking water; they weep over the insufficient food before being given manna, then learn only by trial and error not to gather it on the Sabbath; and are viciously attacked by Amalek, fending them off only with a dramatic effort. It is among the more eventful interludes of the journey, one which prefigures the more explosive and deadly uprisings that begin the chain of rebellions in Numbers 11. Earlier texts grapple directly with the shock of these crises, which occur right after we are told in Exodus 14:31 that the people “believed in God and in God’s servant Moses.” They speculate that God waited six weeks to give them the Torah because they were simply not yet capable of bearing its intensity when they first departed. At a minimum, they recognize that Israel betrayed God’s trust and incurred God’s wrath, and had to seek forgiveness before they could stand before God at Sinai.

The Pesikta recalls this period somewhat differently. First, it considers why God waited until the third month to give them the Torah.

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 12:3

R. Levi said: It is like the son of a king who recovered from his illness. His tutor said he must return to school. The king said, “The shine has not yet returned to his face; should he return to school? Rather, let him relax in comfort with food and drink for two or three months and then he will resume his studies.” So too, as soon as Israel left Egypt they were worthy to receive the Torah, but some among them bore injuries from the oppression of bricks and mortar. God said, “The shine has not yet returned to their faces; should they receive the Torah? Let them relax in comfort for two or three months with the well, the manna, and the quail, and then they will receive the Torah.”

This is a surprising parable for the leadup to revelation. It introduces a figure who has no analog in the text itself, the severe and insistent tutor, who urges that the child, recovered from illness, return to school. It also frames the giving of Torah as parallel to attending lessons, an important yet perhaps tiresome and laborious task from which a recovering child would desire temporary reprieve. But it is the king’s role in this episode that is truly novel. God is often pictured in rabbinic texts as a parent, often loving and forgiving but always demanding. Here, the demanding voice is given to another, allowing God to appear as the doting parent who wants to coddle and pamper the child.

The Pesikta is clear—and makes explicit elsewhere—that Israel is fully capable of receiving Torah the moment they leave Egypt, and God knows this. But God also sees that the experience will be stressful and trying, and thus chooses to give them two or three months (“in the third month” here morphing into “after three months”) to relax and regain their vigor, luxuriating in the invigorating powers of the well, manna, and quail to better prepare them to receive Torah. Here too, as in the wedding imagery, the roles have been reversed. Israel, though bruised and beaten, is strong and capable, ready for whatever is necessary. It is God who delays out of a feeling of doting care, wanting to give the Israelites time to fully heal before facing the labor of learning.

Key to this transformation is the recasting of the events of Exodus 16 as positive and restorative. In Exodus, God gives the well water only after the people complain bitterly to Moses (15:24), while the manna and meat come only after the Israelites, torn by hunger, recall Egypt as a place where they “sat by pots of meat and ate our fill of bread” (16:3). But in this retelling, these are gifts given by a loving God meant to restore them to health and prepare them for the long road ahead.

We see that same transformation in this midrash, which returns to the image of God as groom:

Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 12:11

R. Lazar said: Like a king who wished to marry a well-born noblewoman, and said, “I will not wed her without wooing her. I will give her gifts and only then wed her.” He saw her at the baker and filled her arms with loaves; at the tavern, he gave her spiced wine; at the butcher, he gave her fowl; at another, he gave her choice meats; at another, dried figs. At the baker, he filled her arms with loaves: “Behold, I will rain upon you bread from the heavens” (Exodus 16:4). At the tavern, he gave her spiced wine: “Then Israel sang this song: Spring up, O well—sing to it” (Numbers 21:17). At the butcher, he gave her fowl: “And God swept quail from the sea” (Ibid. 11:31). At another, he gave her dried figs: “God fed them honey from the rock” (Deuteronomy 32:13).

Here again is our king, nervous and excited, wooing an honored and noble bride. It would be unworthy of her to marry her in a rush without a proper courtship, so he walks with her through the market, and at each stall buys her the choicest delicacy. Laden with these gifts, her honor duly recognized, the king finally feels worthy of her hand. It is a charming image, and quite unusual in portraying the king as the petitioner seeking to win over a bride, rather than enthroned in the seat of power, petitioners approaching him. And at its heart, again, are the water, manna, and quail from Exodus 16, reframed as gifts of love and devotion. This story answers the same two central questions about the journey from Egypt to Sinai as the last: Why did God wait until the third month to give Israel the Torah, and what is the meaning of the events that took place in between? And it gives, in essence, the same answer: the waiting reflected God’s care and respect for Israel—such a bride should not be rushed—and the foods were gifts of love, meant to demonstrate those feelings.

This is, of course, a sharp departure from the original story, in which one might question, reading it for the first time, whether Israel would even make it to Sinai. It is, in truth, a new story, one that portrays a different kind of relationship that invites its readers to hear a different tone in God’s voice.

I do not mean to suggest in any way that the rabbis were falsifying or tampering with a sacred tale, that they were somehow doing damage to the original story. They were instead engaging in what we would call revisionist storytelling, using the elements of the familiar narrative to weave a new tapestry. Beginnings are highly symbolic: they set the frame for everything that comes after. This is especially true in the Torah. The creation story is a forceful statement about what it means to be human. The core statements about being an Israelite always hearken back to God’s call of lekh lekha, and our story as a people is eternally shaped by the Exodus. Revelation is the founding moment of our relationship with God and, even more to the point, of God’s relationship with us. The story we tell about how God related to us in that crucible moment is a stand-in for how we imagine God relating to us in the present.

The story that the rabbis always told each other was itself a revision of the original. It depicted God revealing Godself in dialogue with Moshe, sharing Godself, and in return expecting total commitment, a life that revolved around God’s word. It was the story of the academy, and indeed one that often pictured God sitting in a heavenly academy or even observing the debates in the rabbinic one below. It was, we might say, the story of the God of laws and details, of Mishnah and Talmud. But in fact the Torah was given to—and was meant for—all of Israel. And when the rabbis had the opportunity to bring that Torah to all Israel, to speak to and for the community as a whole, they found that they needed a new story of revelation. They listened to their audience and felt how they were burdened by the chains of oppression. And they understood that they needed to hear not the voice of God’s commands but the voice of God’s love; not halakhah but aggadah.

They began to speak of God as suitor, of Israel as honored and desired in a world where they were demeaned and beaten down. They spoke of God as doting father, wanting his child to learn and grow but wanting above all to shield him as long as he could from the world’s harshness. The rabbis in this era of Midrash Aggadah use the story of revelation to convey to their community a fundamental truth that can easily be lost in the thicket of law and commandment: that God’s love is unconditional; that we, as Israel and as human beings, are noble and worthy of God’s love; and that God has infinite patience and will joyfully embrace us when we ask. It is, I believe, in Midrash Aggadah, in learning to speak to the hearts of their congregations, that the rabbis truly rediscover the God of love.

[1] See for example the formulation in David Hartman, A Living Covenant : The Innovative Spirit in Traditional Judaism (2013), part 2. Abraham Joshua Heschel makes the case that this represents a dramatic and intentional rabbinic shift in Torah min HaShamayim, translated by Gordon Tucker as Heavenly Torah (2006).

[2] The centrality of this theme in the Pesikta is explored at length in Rachel Anisfeld, Sustain Me With Raisin-Cakes: Pesikta deRav Kahana and the Popularization of Rabbinic Judaism (2009).

[3] See discussions in Seth Schwartz, Imperialism and Jewish Society: 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. (2001), chapters 9-10; and Lee Levine, The Ancient Synagogue (2008), ch. 7.

[4] For example, Mekhilta D’Rabbi Ishmael 19:17.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.