Yehiel Poupko

Why bother setting the stage with the environment? Everyone knows what the weather was like on a wintry Moscow day, February 22, 1989. What is not well-known is the atmosphere in the House of Sciences, a club for Soviet scientists on Kropotkinskaya Street.

The walls of the science building were suffused with decades’ worth of lies. In the audience that afternoon were officials of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and two or three past and present members of the Soviet Politburo. In addition, there were scores of Soviet Jews, some of them accompanied by a personal KGB officer. Some had jail records. Most had been living in defiance for several decades. They had been immersed in the study of Hebrew or the study of Tanakh, some in the study of Talmud, all longing to live in Israel and be united with the Jewish People.

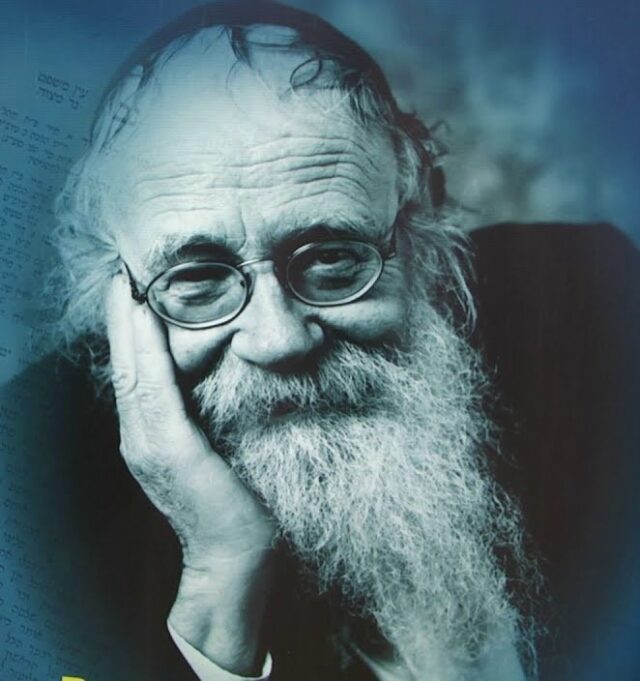

On the stage in the House of Lies stood ha-Rav Adin Steinsaltz. The Soviet Academy of Sciences had decided that a Yeshiva, or, to be more precise, a Department for the Study of Jewish Civilization, could be opened in Moscow. It all started a year earlier at a meeting of the Parliament of World Religions in Britain. As the Rabbi recalled, he was walking across one of the lawns at Oxford with the number two person in the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Rabbi Steinzaltz inquired, “You are a great academic institution, like the Sorbonne, like Oxford, like Cambridge, like Harvard, Yale, Princeton?” Of course, the official said, “Yes!” The Rabbi then said, “Well, they have departments for the academic study of religion, such as Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and, by the way, Judaism as well. How can you be a great university on the par with other world class institutions when you don’t have a Department of Religion?” Nine or ten months later Rabbi Steinsaltz was there to inaugurate the Yeshiva. Other religions were invited to open programs, but they couldn’t quite get their act together. In exchange for this opportunity, the Rabbi helped raise the funds necessary to microfilm all of the Soviet Academy’s Judaica holdings.

At first glance, Rabbi Steinzaltz’s success seems inexplicable. For decades, Jewish leaders from Western Europe and North America had visited with Soviet officials to ask for a particular publication or school to be founded or to plead that a synagogue not be closed. Rarely did much of anything come of this. These requests were always addressed Soviet government’s Ministry of Cults. Rabbi Steinsaltz understood that the purpose of the Ministry of Cults was not to cultivate religion. He grasped something that had eluded the leaders of diaspora Jewry. The doorway to teaching Torah in the Soviet Union was in an academic institution, not in a ministry designed to perpetuate religion. That is what brought him on that winter’s day to the House of Sciences.

Rabbi Steinsaltz stood on the stage of the House of Sciences, supported and backed by no government, no official institution in the West, and no international body. He was appropriately introduced with a simple, well-earned title. The moderator said, “I give you today’s Hatan ha-Torah, ha-Rav Steinsaltz.” The Rabbi was not triumphal. He did not stand with his head held high, his shoulders rising to the full height of his stature, which, in any event, wouldn’t have been that tall anyway. He stood with his smile, the radiance of his eyes, and he began teaching the first Mishnah that the new Yeshiva would study, Arvei Pesakhim. Except for a few westerners, almost no one in the room had ever heard him speak before. This was the first officially sanctioned limud Torah in Soviet Russia since the Bolshevik coup d’état of 1917.

At this understated epoch-making event, Rabbi Steinsaltz brought only two offerings. The first was the Mishnah he taught. The second was his neshamah, his very being, which was suffused with boundless ahavah — ahavat Hashem and ahavat Yisrael, cloaked in the warmth and radiance of his personality. More was not needed. Neither Russian culture nor Soviet society knew a man of such assets.

How did this come to be? How did a rabbi, a man of Chabad principles and Haredi appearance, come to be standing in the House of Sciences under the sponsorship of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, an institution which did its fair share to deprive many people of livelihood and basic human rights? How did such a man come to be at the Parliament of World Religions seemingly and casually bumping into an official of the Soviet Academy of Sciences? What was he doing at the Parliament of World Religions in the first place? Who is this man?

This essay contributes nothing to the basic biographical data about the life, education, development, and family of Rav Steinsaltz. All that has, in the weeks since his passing, been well-publicized. Instead let’s begin with a facet closely associated with his appearance at the Academy of Sciences: the rabbi was educated in science and mathematics. Indeed, it is not a coincidence that Rabbi Menahem Mendel Schneerson, the last Rebbe of Habad, was similarly educated. This was no coincidence: in the all-encompassing life philosophy of the Tanya, the foundational work of Habad upon which Rav Steinzaltz wrote a commentary, everything in material reality – nature, the human being, community, and social reality – is imbued with the divine, is an expression of the divine, always benefiting from the radiance and flow (shefa) of the divine.

Accordingly, there are opportunities for one to encounter the divine and raise levels of holiness and purity in all of life’s experiences. For Rabbi Steinsaltz, a variety of human expressions of the divine intellect in philosophy, history, languages, mathematics, sciences, and the arts were familiar to him. He was at home in many realms of the human endeavor. He was a renaissance man who encompassed more than just the humanities, the sciences, and the arts. As a polymath and as an autodidact, he acquired residence in all the homes of Torah, Tanakh, Torah she-be’al Peh, philosophy, Kabbalah, and Hasidut. He had a unique capacity to talk to and be at home with so many different people immersed in so many disciplines and arts. This is why all sorts of people from many walks of life sought him out.

How did Rabbi Steinsaltz achieve all that he embodied? We are handicapped in our times; we try to understand a person in what popular language calls feelings and emotions. We reduce charisma to social circumstance. As a consequence of living in the age of the triumph of the therapeutic, ideas and thoughts are attributed to personal circumstance and feelings. For this reason, we do not take the time to understand and appreciate that very often what we call emotions are intimately bound up with expressions of ideas and principles. For Rabbi Steinsaltz, love was not just a sentiment, nor even a feeling. It was a philosophical principle by which he presented himself, the Torah, and his way of emunah: living with God in his personal encounters, in his writing, and in his teaching.

The source for this is found, appropriately, in the Tanya, one of the greatest works of modern Jewish thought. The Tanya is nothing if not a psychological portrait of the divinely endowed soul. Rabbi Steinsaltz became a person after the Ba’al ha-Tanya’s image of the homo religiosus. (As noted, one of Rabbi Steinzaltz’s many great works is his commentary on Tanya.) Put succinctly, the authentic Jewish homo religiosus is one upon whom rests the presence of the Shekhinah.

In that magnum opus, the Alter Rebbe describes a higher form of love. It is in reference to the verse in Tanakh, ahavah ba-ta’anugim, love of delights (Song of Songs 7:7). Rabbi Steinsaltz explains that common love of something else, or of another person, too often involves love of self. As Hasidim used to point out, the expression “they love one another,” in Yiddish (zey hoben zikh lieb) also means “they love themselves.” A higher form of love, ahavah rabbah, is achieved when a person no longer experiences any tension between his divine and material selves, and all his desires are directed to God.

Too often, love is rooted in a desire to accrue what a person lacks. In this higher love, however, as Rabbi Steinsaltz writes, the beloved is loved for its own sake, unconnected with the lover’s needs. The more one thinks about and occupies himself with the object of his love, the more satisfying that love becomes: ahavah ba-ta’anugim.

For Habad thought, the Torah is an expression of the radiance of the Ein Sof, the One and the light beyond all. There is nothing more familiar and attractive to the soul of a Jew — which emerges from the Ein Sof — than the Source itself. Rabbi Steinsaltz, a devotee of the Ba’al ha-Tanya’s worldview and a devoted follower of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, set out to disseminate oceans and oceans of Torah light.

How, then, did Rabbi Steinsaltz come to present to the world all of the Talmud Bavli? The answer lies in the very name Habad, an acronym for Hokhmah, Bina, and Da’at. From its very inception, Habad was about the topography of the soul’s intellect, wisdom, knowledge, and understanding, each of these possessing increasing depth. This should not surprise us. There were always great traditions of immersion in Gemara over the seven generations of Habad Rebbes.

To better understand the intellectual emphasis of Habad philosophy among the varieties of Hasidism, it is worth considering a bit of geography. Lithuanian Jewish civilization was characterized by magisterial Talmudic scholarship, which reached its apex in the Gaon of Vilna and received its lasting institutional expression in the Yeshiva birthed by Rabbi Hayyim Itzkowitz in Volozhin. With its similar abiding commitments to philosophic mysticism and the great traditions of immersion in Talmud learning, it is no coincidence that Habad flourished in this Lithuanian Jewish religious sphere.

In Habad thought, both Nigleh and Nistar – the revealed and the hidden– are animated by the divine light or intellect. With this in mind, we can begin to understand Rabbi Steinsaltz’s approach to — and presentation of — the Talmud. In The Talmud: A Reference Guide, Rabbi Steinsaltz presents a view of lernen that goes well beyond the profound scholarship of the Lithuanian yeshivot as developed in Volozhin and Brest-Litovsk. Torah study makes it possible to learn “the principles and details necessary to fulfill the mitzvot.” However, Rabbi Steinsaltz teaches that “this view of Torah fails to convey its true purpose… It does not explain why Judaism developed such great veneration for the study of Torah.” This is, as he notes, characterized by:

“all things that may be desired may not be compared to it [the study of Torah]” (Proverbs 8:11). This means that even the desires of Heaven [the commandments] cannot be compared to Talmud study. (Moed Katan 9b)

To say that the “study of Torah is equal to all of them” implies that Torah study is at a higher level than performing the commandments.

Thus, for Rav Steinzaltz, we don’t just study the Torah to help us fulfill the mitzvot. It is not just a utilitarian tool. The Talmud is a comprehensive guide, the expression of Judaism’s conception of Everything. Every subject lies within the corpus of Torah. Torah teaches us how every subject is to be understood, how we should relate to it and act toward it.

Hence, it makes no difference “whether the subject is concrete and practical or abstract and spiritual.” In other words, in Rabbi Steinsaltz’s conception, which has also its roots in the teachings of the Alter Rebbe, every part contains the whole within it. The Talmud presents the proper way in which to view all of material, social, and spiritual reality. Through his many writings and talks, the Rabbi was able to link the immediate realm of material being with Olam Habah. These worlds of potentiality are not just lodged in the future. They are with us. We need only open our divine soul to experience them.

Often, when he was asked to teach a passage from Tanakh, he would turn to Psalm 139, which contains the following verse:

It was You who created my conscience; You fashioned me in my mother’s womb. I praise You, for I am awesomely, wondrously made; Your work is wonderful; I know it very well. (Psalms 139:13-14)

These verses describe the immediacy of the divine caring presence from the moment of conception through all of life. It is these immediate and parallel realities to which the Talmud lends meaning. For him, God’s love of every Jewish person must then be expressed by every individual who has received that love, by extending it to all Israel. Therefore, when Israel grows distant from God there is only one response that a great lover of Israel and Torah can have: Israel and its Torah must be reunited.

In conceptualizing how this principle applies in our time, Rabbi Steinsaltz emphasized a somewhat overlooked event in twentieth-century Jewish history. Surely, the destruction of European Jewry, followed by the establishment of the State of Israel, followed by the liberation of Soviet Jewry were monumental events. Yet, there is an event that preceded all these. The Rabbi noted that, by the time World War I had begun, a majority of the Jewish People were no longer keeping the mitzvot in the traditional sense of the term.

When the Lubavitcher Rebbe passed, the Rabbi was interviewed by Ted Koppel on Nightline. It was not an easy time for him. He had fallen and broken an arm so he was bound up in a sling. And he was in deep mourning.

Koppel asked him what was unique about the Rebbe. Rabbi Steinsaltz responded, “It is given to very few in Jewish history to reverse the course of Jewish history. The Temple was destroyed. No one has yet been able to reverse that. Whole Jewish civilizations in Arab lands and European lands have been destroyed. No one has been able to reverse that.”

Rabbi Steinsaltz then noted, “Facing the profound decline in the observance of mitzvot that overtook the Jewish People in the early twentieth century, along with its attendant assimilatory trends, the Rebbe reversed the course of history. He brought more and more people to lives of mitzvot, to lives of Torah learning, to lives of love of Israel. The Rebbe reversed the course of history.”

Rabbi Steinzaltz’s larger project – and his appearance in both the Academy of Sciences and Yeshiva in Moscow – now become clear. His efforts to bring the entire corpus of Jewish learning to the Jewish People was also meant to reverse the course of Jewish history. Along with assimilation and along with a decline in Jewish practice came profound ignorance. In response, the Rabbi’s motto was “Let My People Know.”

Inspired by his Talmud, one day a Jew far from practice and far from knowledge came to see him. This Jew, head of an internationally important Jewish organization, began to talk with the Rabbi about his Jewishness. Finally, this articulate man who was capable of Demosthenes-like oratory in the public realm began to stutter and stammer. He said to the Rabbi, “I don’t know what’s happened to me.” The Rabbi looked at him and said, “You have ancient voices in you that are trying to get out.” This Jew broke down in tears. Rabbi Steinsaltz heard the ancient voice that is in every Jew. He set himself the task of giving word and speech and articulation to those inchoate ancient voices.

***

As far as I can tell, Rabbi Steinsaltz is the only person whose family name was changed by the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Steinsaltz is German for stone salt. The name is probably vocational in origin. Jews in Eastern Europe, especially in Poland and Ukraine, made commerce from salt stones, or salt licks. The Rebbe changed his name to Even and suggested that the Rabbi, if he liked, could add to it. He did. Rabbi Steinsaltz added the word Yisrael. The Rabbi surely understood what the Rebbe intended. As a master spiritual figure, the Rebbe would often indicate the direction, and his interlocutor would then have the task of identifying the end to which this direction might lead. When Yaakov gives his berakhah to Yosef he declares:

ותשב באיתן קשתו ויפזו זרעי ידיו מידי אביר יעקב משם רעה אבן ישראל׃

Yet his bow stayed taut, And his arms were made firm By the hands of the Mighty One of Jacob — There, the Shepherd, the Rock of Israel — (Genesis 49:24)

One of the features of Habad Hasidism is that there really are no secrets. What we think are secrets in avodat Hashem are really right there for everyone to see and experience. All we have to do is to open our eyes. When we open our eyes to this verse and look at its context, what do we read? From there will come a shepherd, the rock of Israel.

The Rabbi often inspired others with stories. On that first Friday night after the Yeshiva opened in Moscow, he was sitting together with many of the students and their families. Before he made Kiddush, the Rabbi told a story from the Besht. It was the practice of the Besht to light many, many candles to bring in Shabbat. He was asked why. He taught: the gematria (numerical equivalent) of light, is 207. The numerical equivalent of raz, meaning secret and mystery, is 207. The Besht asked, “How is it possible that these two words should be so intimately related and bound up with each other? Radiance and light banish and uncover mysteries and secrets. Radiance and light are the enemy of secrets.” The Besht explained that secret and light have the same numerical equivalent because the greatest secret of the Jewish People is that we have no secrets. What we have, anyone can see just by opening up their eyes to the light. This was true of Rav Steinzaltz and animated his entire worldview and life project. Elokut is at hand.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.