Ross Singer

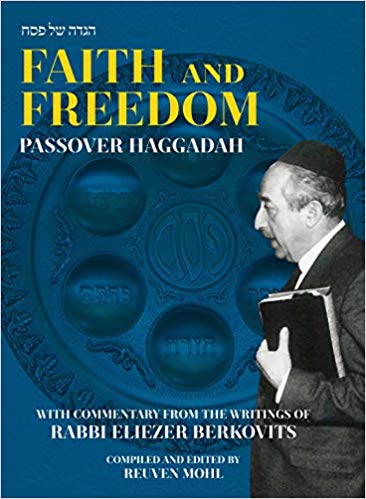

Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits was one of the most creative and radical thinkers in Modern Orthodoxy. Some have placed him outside the camp of Orthodoxy, yet others have heralded his work and called for its reexamination. For nearly two decades, his writings have been republished in both Hebrew and English.[1] Academics and scholars have been producing essays and books exploring the relevance and significance of his intellectual legacy. The latest addition to this growing collection is the Faith and Freedom Passover Haggadah with Commentary from the Writings of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits, compiled and edited by Rabbi Reuven Mohl.

Rabbi Mohl in his introduction to the volume describes his early fascination with R. Berkovits’ work and his more recent undertaking “to read through his entire oeuvre” (11). Indeed, his mastery over all of R. Berkovits’ corpus is evident in the wide-ranging selections in this Haggadah. He includes some of his lesser-known writings, such as the fascinating collection of sermons, Between Yesterday and Tomorrow. The reintroduction of these more obscure works takes the renewed interest in R. Berkovits’ legacy to previously neglected horizons.

While completing his survey, Rabbi Mohl noticed that there were “many themes tied to the Haggadah” in R. Berkovits’ corpus and so he “began to organize a Haggadah commentary compiled from his writings” (11). Rabbi Mohl is certainly correct that much of R. Berkovits’ writing is extremely relevant to the Haggadah and the perennial Jewish narrative arc of exile to redemption. R. Mohl has done us a great service by connecting these themes in R. Berkovits’ writings with relevant passages in the Haggadah.

Notwithstanding this service, sometimes the connections between the extracts from R. Berkovits’ writings and the text of the Haggadah seem artificial and forced. For example, the mention of Rabbi Eliezer in the Haggadah’s telling of the Seder in Bnei Berak is used as a springboard to explore the dispute between Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua over the oven of Akhnai. In this well-known Talmudic story, Rabbi Eliezer calls up Heaven to prove that his position is correct. A heavenly voice indeed proclaims that the Halakhah follows Rabbi Eliezer. Rabbi Yehoshua and the other Sages reject the heavenly voice (Bava Metzia 59b).

R. Berkovits uses this story to demonstrate how essential are human responsibility and subjectivity to the halakhic process. “What God desires of the Jewish people is that it live by His word in accordance with its own understanding. In theoretical discussions man strives to delve into the ultimate depth of the truth; but when he decides that he has reached it, it is still only his own human insight that affirms that indeed he has found it … The result is not objective truth but pragmatic validity” (43)

While this is one of R. Berkovits’ important and idiosyncratic positions regarding his philosophy of Halakhah, it is hard to see its relevance to the themes of the Haggadah. The only apparent link is the mere mention of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua in the Haggadah, and their appearance in the oven of Akhnai story. The Bnei Brak Seder in the Haggadah has no clear connection to their dispute.

Another theme is tenuously tied to this same passage. The Bnei Brak Seder is cut short at daybreak, as the time for the recitation of the morning Shema has arrived. This affords R. Mohl the opportunity to share R. Berkovits’ understanding of R. Akiva’s recitation of Shema at his martyrdom (43-44). Unlike other martyrs who recited the Shema as a spontaneous dramatic final declaration of faith, Rabbi Akiva’s recital of Shema was “at the appointed time of its recitation.”

R. Berkovits explains that R. Akiva’s recitation of Shema points to an alternative type of resistance to oppression that was common in the ghettos and death camps of the holocaust—the act of ignoring the horrific circumstances of persecution, and continuing “about the business of living the daily life of a Jew.” Rabbi Akiva’s recitation of the Shema “at its appointed time” typifies this type of resistance. The only link between the Haggadah and R. Berkovits’ interpretation of Rabbi Akiva’s martyrdom is the mention of “the appointed time to recite the Shema” at the Bnei Berak Seder.

Some other examples of resistance in the camps from R. Berkovits’ writings are at least somewhat more closely related to the Seder. The mention of the bread of affliction in Ha lahma anya, for instance, serves to recall the Jews in Buchenwald who, on Pesah 1945, gave up their bread ration in the camps for small portions of thin soup. One of the survivors noted, “It may well be that their determination not to partake of bread, notwithstanding the starvation, equipped them with strength beyond that of other camp inmates” (35-36).

Similarly, Kadesh serves as the backdrop to introduce a historical halakhic discussion of the appropriateness of making Passover kiddush in a concentration camp over bread when that was all that was available to the starving inmates. Unlike the previous excerpts, these last two are directly connected to Passover. Still, it is hard to see even these passages as illuminating the text of the Haggadah in any but the most oblique of ways.

These tangential connections to the text of the Haggadah allow R. Mohl to introduce themes from the wide scope of R. Berkovits’ thought, including the importance of the Hebrew language (25), R. Berkovits’ insistence that Halakhic decision making must yield ethical conclusions (39), his position that Halakhah must reexamine the status of women in modern times (48-49), divine affirmation of the material world and the human body (26-28), the proper attitude towards secular studies (86, 104), the Jewish insistence on deeds against Paul’s polemic for faith over law (50), and numerous other important topics. If intended to introduce the uninitiated into the breadth and depth of R. Berkovits’ thought in a popular format, then the awkward connections can be understood. However, for this reader they were distractions from the most powerful aspect of the book: a reframing of the Haggadah’s recounting of the Exodus saga through the prism of R. Berkovits’ theology and philosophy.

Like many thinkers in the Religious Zionist camp, R. Berkovits puts great emphasis on interpreting history. However, while many attempt to identify individual historical events of the past century or so as fulfillments of biblical prophecies or rabbinic proclamations about redemption, R. Berkovits is interested in the larger arc of Jewish history. He explores the theological significance of the powerlessness of exile, the persistent aspiration for redemption, and the meaning of its fulfillment. His original interpretation of the classic narrative of slavery to freedom provides a deeply challenging and meaningful retelling of the story of the Exodus.

The Haggadah’s most succinct summary of the Exodus narrative states, “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and the Lord, our God, took us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm” (37). It is natural to look to God’s salvation to find the theological significance of the story. However, Rabbi Berkovits’ thought draws us to focus on the theological significance of the subjugation and exile of the story.

R. Berkovits notes that exile

“stands at the very beginning of the road. It all started with the call to Abraham: ‘Get thee out of thy country and from thy kindred and from thy father’s house, unto the land that I will show thee…’ When the father of the nation-to-be was still childless, it was already decreed and revealed to him ‘Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years’ … even before there was a Jewish people there was already Exile and promise of Redemption (53-54).”

From this R. Berkovits concludes that “most of the following exiles of the children of Israel were not God-ordained punishments but man-imposed persecutions” (37). And so the question that begs to be answered is, what is the significance of powerlessness and exile that is inherent in the Jewish experience?

While the overpowered status of the People of Israel should not be taken as divine punishment, it is not without theological significance. R. Berkovits explains that the experience of the subjugation in Egypt was a crucible intended by God to inculcate in His people a humility and a distaste for power. However, the experience of the Egyptian persecution was too overwhelming: “Had the Egyptian slavery lasted any longer, it would have completely broken the nation … (God) could only partly achieve His purpose with them, because the trials of their slavery exceeded their ability to suffer” (84).

Because the experience of Egyptian subjugation was too extreme, God had to cut short the lesson of exile before it could be fully apprehended. This is why the Israelites had to leave so quickly; this is why there was no time for the dough to rise. Yet this premature salvation would come at great costs in the future: “Israel was saved from destruction; (but) it was not yet mature for its mission. Hence, failure followed upon failure. The nation even lost its Homeland and was sent into the Galut once more, to learn the rest of the lesson (84).”

The experience of Galut in Israel’s initial stages was intended not only for Israel’s benefit but also to teach all of humanity: “God needs a small and relatively weak people in order to introduce another dimension into history—human life—not by might, not by power, but by His spirit … He could not associate His cause with the mighty” (25). Only a weak people that is committed to forgoing brute force can teach the world that might does not make right. The powerlessness of the Jewish people is part of the divine plan. For a people to be God’s chosen people, they must not have or make use of brute force. Powerlessness and exile are built into the very project given to the Jewish people.

This theological interpretation is particularly poignant, as R. Mohl juxtaposes it with the passage “Not only one enemy has risen against us to destroy us, but in every generation they rise against us to destroy us; and the Holy One Blessed be He saves us from their hand.” Upon this we read, “The survival of a people that has lived without power is inexplicable in a world that lives essentially by reliance on power” (56-7). The Jewish people is an entity devoid of political power that somehow survives in a world of realpolitik.

R. Berkovits explains that the Holy One saves Israel despite their lack of overt power. “The secret is God’s hidden presence in history. It consists of God’s power-divested guidance in history. Because it is “powerless” it is hidden; yet its reality is intimated in the inexplicable survival of God’s people” (57). While some might focus on the miraculous power of God’s outstretched hand at the Seder as the most theologically significant gesture, R. Berkovits turns us away from the plagues and the splitting of the sea. The most theologically significant moments of salvation are the ones that took place “in every generation,” by God’s hidden “power-divested guidance in history.”

Accordingly, impressive miracles undermine the more regular and hidden divine guidance, the purpose of which is to manifest the message of “not by might and not by power” (25). Yet this is not the only problem with miracles. They also undermine human freedom and thereby human responsibility. “Manifest divine intervention would subjugate man and destroy that very freedom without which he cannot be human” (76). This explains “the rabbinical dictum that one must not rely on miracles. For man has been called to fulfill his humanity in responsible action.”

We must then ask, what is the significance of all the miracles in the Exodus narrative? R. Berkovits explains that, sometimes, the freedom that God grants humanity can bring the world to the brink of collapse. “For the freedom that allowed him to continue the works of Creation may also be used for the [destruction} of man and the world. Man’s own exercise of his freedom may at times necessitate God’s corrective intervention.”

One might ask if R. Berkovits’ continual deemphasis on both God’s and Israel’s manifest power can be reconciled with the age-old longing for redemption. Isn’t the longing for redemption a deep-seated aspiration for a final vindication of the Jewish people through the establishment of a dominant and powerful Jewish polity? R. Berkovits insists otherwise. In fact, we should take satisfaction in having eluded the curse of political power all these years.

Echoing Rav Kook’s seminal first essay in his book Orot, R. Berkovits writes that the powerlessness of exile has “been unpleasant, but, we say, thank God for it … Let us be grateful to the Galut; it has freed us from the guilt of national existence in a world in which national existence meant guilt. We have been oppressed, but we were not oppressors. We have been killed and slaughtered, but we were not among the killers and slaughterers” (63).

Both Rav Kook and Rabbi Berkovits had to conclude that there must be something different about the age of redemption that will allow the people of Israel to manage a polity without brute power. Rav Kook the optimist believed that “it will soon be possible for us to govern our nation by principles of goodness, wisdom, rectitude, and divine enlightenment” (Orot, 14).

R. Berkovits, living after the Holocaust (Rav Kook died in 1935), could not justify such optimism. Instead he concluded that in a post nuclear world, “man, having amassed so much power that he is able to destroy life and civilization on a global scale, must learn to renounce power as a means of ordering or controlling relations between people and nations … This is no longer mere sermonizing; it has become the “iron law” in the new phase of global history. Be decent or perish!” (Faith After the Holocaust,139) It is only in this era, when nations must renounce using their full arsenal of power, that the Jewish people can enter the stage of politics.

While R. Berkovits emphasizes the prophetic vision of world peace for the end of days, he insists that “the universal expectation is inseparable from Israel’s homecoming … The redemption of mankind includes the redemption of the Jewish people in the land of the Jews” (46-47).” If Jewish dominance and political power is not the fulfillment of the redemptive posture, why this insistence on a return to the Land of Israel and Jewish sovereignty?

Rabbi Berkovits explains that “the structuring of the whole of life, personal and communal, economic, civic, social and political, that the Torah prescribes, the all-comprehensive deed which is required can ideally be achieved only by a community that is in control of its daily life.” Only a sovereign nation can play out the message of the spirit over might and power in all aspects of human endeavor. Redemption, for R. Berkovits, is the ability to apply the lessons of the experience of a powerless exile to the smallest unit of fully constituted human experience: the nation.

To summarize R. Berkovits’ conception of Jewish history: The Israelites could have expected the subjugation and suffering that became their lot. The exile had a pedagogic element for Israel itself. It is also part and parcel of the role of being God’s chosen people—chosen to teach that one must act in this world by the spirit and not by might and power. The most significant manifestation of God’s salvation is not in the pyrotechnics of the miraculous exodus. It was unfortunate that God needed to intervene in a way that undermined human freedom.

Moreover, had the Israelites had the wherewithal to withstand the Egyptian subjugation they could have learned completely the lessons that exile was intended to teach. The premature and hasty exodus would ultimately lead to other national misfortunes. Rather than the miraculous exodus, it is the mysterious sustained existence of the people Israel that best demonstrates a supernatural guiding presence in the world.

This subtle divine protection of the relatively powerless Israel throughout history teaches the great lesson of the spirit, morality, ethics, and compassion. In our post nuclear world, where restraint of power is necessary for survival, the Torah ethic of spurning power is ascendant. It is in this era that the return of Jews to their homeland and to sovereignty has taken place.

The return to the Land and sovereignty is not the end of the story. R. Mohl brings the following passage as a comment to the Haggadah’s closing line, Next year In Jerusalem: “The restoration of Jewish sovereignty in Zion is not a goal in itself … Political sovereignty is only the framework within which this remarkable people of history may lead its life according to its own vision and create a culture whose essential resources can only be of the spirit (142-143).”

This unconventional, and perhaps counterintuitive, conception of Jewish history is the legacy of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits’ historiosophy. Rabbi Mohl has done a wonderful job of juxtaposing and interpolating that thought into the text of the Haggadah. Whether or not the Haggadah can bear this interpretation, I leave for the reader to decide.

In their Forward to this Haggadah, Rabbi Berkovits’ sons write that at their father’s Seder, when the door was opened for Elijah, “our father z”l would say quietly in his clear baritone, ‘Baruch Haba, Rebbe’ (Welcome, my Rebbe). It was clear to all of us that the prophet was actually present and, more, that he carried with him the secret of Jewish history in its entirety” (8). After reading Faith and Freedom, I too feel I will be able to say at my Seder this year Barukh Haba to Rabbi Berkovits, and that his spirit will be present, bearing the secret of Jewish history in its entirety.

[1] Examples include Essential Essays on Judaism (Shalem Press 2002); God Man and History (Shalem Press 2004); עמו אנכי בצרה, הוצאת שלם בשיתוף יד ושם, ירושלים, תשס”ו.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.