David Selis and Zvi Erenyi

In 2013, Professor Menahem Schmelzer, of blessed memory, published a memorial to his own beloved teacher, the Hungarian scholar Alexander Scheiber, entitled “Scheiber’s Beloved Books.” Prof. Schmelzer wrote that Prof. Scheiber, rector of the Jewish Theological Seminary of Budapest, “had three loves: books, people and learning.” This statement is as applicable to the student as it was to the teacher. Continuing the chain of tradition, I offer this tribute to Professor Schmelzer—a true lover of the Hebrew book.

Professor Menahem Hayyim Schmelzer, the Albert B. and Bernice Cohen Professor Emeritus of Medieval Hebrew Literature and Jewish Bibliography, and Librarian at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, left us for the heavenly beit midrash on December 10th, 2022, the 16th of Kislev, 5783. Professor Schmelzer was a consummate mensch, a wide-ranging scholar, and the doyen of Hebrew bibliography and piyyut (poetry) for two generations of American scholars.

Professor Schmelzer was born on April 18, 1934, in the village of Kecel in southern Hungary. He and his family were deported to Auschwitz in 1944. Fortunately, their train was diverted, and they were sent to the Strasshof labor camp near Vienna, thereby surviving the War. After the Shoah, the Schmelzer family moved to Budapest, where Menahem Schmelzer studied at the University of Budapest until March of 1953, when he was arrested for Zionist activities and imprisoned for a year and a half. Upon his release, Schmelzer studied at the Jewish Theological Seminary of Budapest from 1954-1956, fleeing during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 to Denmark where he first worked as a librarian in Copenhagen. In 1961, while working at the manuscript department of the Jewish National and University Library (now the National Library of Israel), he married Ruth Blum. The couple immigrated to New York, where he immediately took up a position at JTS. Prof. Schmelzer was a faculty member at JTS from 1961 until his retirement in 2003. From 1964 to 1987, he served as Librarian, and skillfully led the recovery efforts following a disastrous library fire in 1966. Professor Schmelzer was the mentor par excellence, giving of his time freely to even the youngest students.

I first met Professor Schmelzer in 2014 while working at the JTS Library, sorting uncatalogued materials to identify rare items for inclusion in special collections. While Prof. Schmelzer had by then been retired for a decade, he was still a presence in the library. I often consulted him to identify incomplete copies of books damaged by the fire and saved thanks to his tireless work as librarian. Invariably, he would instantly identify the most interesting titles, and without consulting any references, proceed to explain their importance. Later, as an undergraduate, I was reintroduced to Prof. Schmelzer by his grandson, Avinoam Stillman. I had become interested in the history of the JTS Library, for which Prof. Schmelzer served as the keeper of institutional memory. He graciously welcomed me into his home, and thus began hundreds of hours of conversations in his book-lined dining room. During those visits, Prof. Schmelzer’s giving nature, humor, and menschlichkeit were an inspiration. He encouraged my research, commenting extensively on my early papers, and directing me to often overlooked sources. Frequently, he would mention a source and then point me to the shelf in which it could be found, all by memory. As my research progressed, always guided by Prof. Schmelzer’s impeccable memory and utter command of the literature, I sensed a deep kinship in his writings with the father of Hebrew bibliography, Moritz Steinschneider, and the legendary and foundational JTS librarian, Alexander Marx.

Sitting with Prof. Schmelzer, I was transported back in time to another world of Jewish life and culture, with conversation flowing from books, bibliography, and piyyut to the Wissenschaft des Judentums (Academic Study of Judaism) movement, to contemporary scholarship, and Hebrew and English literature. During these conversations, I was introduced to some of his and Ruth’s favorite Hungarian dishes, which Mrs. Schmelzer lovingly prepared for me. I cannot remember a time when we would meet that there was not a stack of books on the table that he and Ruth were reading. There were always dried fruits, nuts, and chocolates. Beyond scholarship, the Schmelzers were eager to hear about my life and my family, including my father, who had been a student of his at JTS. My dad recalls studying medieval Jewish poetry, the subject of Prof. Schmelzer’s dissertation, and a significant focus of my father’s scholarship as a student:

I studied the poetry of Yehudah HaLevi with Prof. Schmelzer nearly 30 years ago. A significant portion of the class focused on the “Zion poems” that were later adopted as part of the Tishah be-Av kinnot. I can still quote from those poems by memory, in Hebrew that is peppered with Prof. Schmelzer’s beautiful East European accent. Those words and that man left indelible memories, ones that have guided me for a lifetime.

As I began my graduate studies at Yeshiva University’s Bernard Revel Graduate School, my conversations with Prof. Schmelzer focused increasingly on the broad direction of my research, especially my archival research at JTS. He encouraged me to write about his hero, Alexander Marx, and the network of collectors, book dealers, donors, and scholars who created early 20th century American Jewish libraries. Professor Schmelzer’s investment in supporting younger scholars was a formative influence on my scholarship. I distinctly remember sending him my first serious research paper, focusing on the way that Alexander Marx’s broad conception of the JTS library was crucial to realizing Solomon Schechter’s vision for an American center of critical scholarship in the Wissenschaft model. The paper was well over twenty pages, and I sent it to him in the afternoon after a visit. Mere hours later I received an email with extensive comments on the paper and encouragement regarding the future research the paper had outlined. As a gift upon my college graduation, Prof. Schmelzer gave me a Master of Library Science thesis on the development of the JTS library during Alexander Marx’s tenure as Librarian from 1903-1953, which was then the subject of much of my research. Israeli MA theses are notoriously difficult to locate, and thus this gift enabled me to cite a source which would have been otherwise unknown and inaccessible to me.

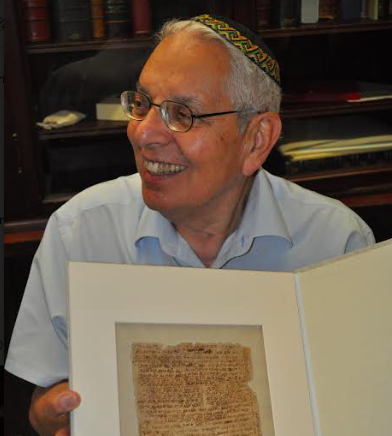

Speaking to a Newsday reporter in 1984, Prof. Schmelzer showed a visually unremarkable manuscript written circa 1200, containing biographies of the Talmudic sages, but notable for its 20th century story. “This manuscript is a survivor, a real survivor,” he said. “It survived from 1200 to 1938, and in 1938 it survived the Kristallnacht. It’s a symbol of continuity, of how it survived the centuries and the tragedies.”

Professor Schmelzer was never imposing, and he shrank from honor. As noted by retired JTS Chancellor Ismar Schorsch in his eulogy, Prof. Schmelzer devoted himself for decades to “an exercise of tehiyyat ha-meitim (resurrection of the dead)” by bringing Prof. Shalom Spiegel’s voluminous notes on late antique Hebrew poetry to print under the title Avot Ha–Piyyut. Prof. Schmelzer rescued his colleague’s work from oblivion, devoting his command of the holdings of the JTS library and the corpus of piyyut to completing Prof. Spiegel’s immense and unfinished project, a profound scholarly hesed shel emet. The fact that Professor Schmelzer is barely mentioned on the title page of Avot Ha-Piyyut—describing himself as merely having brought the work to press when he was virtually the coauthor—is a stunning act of self-effacement.

Such was Professor Menahem Hayyim Schmelzer, a humble giant, who, for me, represented the best of menschlichkeit, love of Torah, and Jewish scholarship— “books, people and learning.” For me, he was a beloved mentor and my tie to generations long past. His work endures and is carried forward by his students and a new generation, such that even in death, the lips of a departed Jewish bibliographer move each time his students speak of a Jewish book or piyyut. May his memory be for a blessing.

David Selis

* * *

My earliest recollection of Professor Menahem Schmelzer is from the early 1970s. My late sister then served as an assistant librarian at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and I was accustomed to frequently visit her there. At that time, a good part, if not the bulk, of the library was housed in a prefabricated structure located on the grounds of JTS, with books arranged on temporary stacks of shelves reaching so high that one needed to climb a ladder to reach the higher shelves. Prof. Schmelzer would come to this so-called prefab to supervise the workings of the staff, headed by the late Mrs. Edith Degani. My objective, apart from seeing my sister, was to note the latest Judaica publications for my own work at the Mendel Gottesman Library of Yeshiva University, which I knew I could rely upon the Seminary Library to have expeditiously obtained, and which were already lined high up on those shelves. Prof. Schmelzer’s deep but surprisingly soothing voice made quite a first impression. His warm smile and immediately sensible and genuine interest in his interlocutor put one at ease. I was allowed to browse the shelves without any hint of jealous competition between the two libraries. He and Mrs. Degani managed to have at that time a first-rate staff at the library, whose members remained there for years, if not decades. His immense knowledge, professionalism, integrity, and kindness fostered, I believe, a loyalty and sense of purpose among the staff which elevated the library above the already high stature afforded it by its rich physical contents.

There were several instances of his involvement with Yeshiva University and specifically the Gottesman Library. When Yosef Avivi began to catalog the library’s rabbinic manuscripts in 1988, he found that Prof. Schmelzer had already prepared a card file with preliminary information on many of them. In 1985, the Gottesman Library sponsored a symposium on the development of Hebrew printing on the occasion of the publication of Gershon Cohen’s Catalog of Yeshiva University’s Hebrew Incunabula at which he delivered a lecture on Hebrew Incunabula – Collections and Research. While on a sabbatical leave from JTS during the 1984-85 academic year, he was appointed Visiting Professor of Hebrew Literature and Bibliography at Yeshiva University, and he assisted in the preparation of the catalog for the Yeshiva University Museum’s 1988 exhibition, Ashkenaz: The German Jewish Heritage. In March of 1986, he participated in a symposium entitled Ashkenaz: Rabbis and Their Books at the Gottesman Library, with a lecture on Rabbinic Publication in Germany in the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Upon his retirement as Librarian in 1986, there was less of an occasion for formal interactions. We nevertheless kept in intermittent touch. A few years ago, his cousin, Rabbi Hermann Schmelzer (since deceased), of St. Gallen in Switzerland, who owned an extensive collection of Hungarian Judaica, decided to sell part of his collection. Professor Schmelzer, knowing that the Gottesman Library already maintained extensive holdings in this field, kindly offered to mediate a sale, which finally took place. A further purchase was sadly prevented by Rabbi Schmelzer’s sudden petirah (passing). This again demonstrated Professor Schmelzer’s unselfish regard for what he judged to be the best outcome from a strictly scholarly point of view, as well as his desire to build Judaica collections.

On a personal level, he was unfailingly kind and solicitous in a way that is entirely uncommon these days. He embodied a unique sensibility, a combination of old-world gentility, and a kind of delicate friendship devoid of any selfishness. We will not see his like again, and we will greatly miss him.

תהא נפשו צרורה בצרור החיים

Tehei nafsho tzerurah bi-tzror ha-hayyim

Zvi Erenyi

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.