Shlomo Zuckier

The story of Pinhas, at its core, is about the use of violent force for an ultimately positive outcome benefitting the common good. Facing a crisis of public sin and divine wrath, Pinhas zealously and publicly skewers the sinning couple of Zimri and Cosbi. The reward for his actions, which stem a terrible plague, headlines his eponymous Parashah (Numbers 25:10-13):

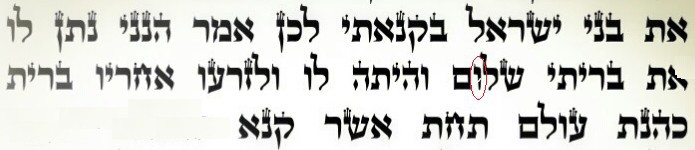

וידבר יקוק אל משה לאמר: פינחס בן אלעזר בן אהרן הכהן השיב את חמתי מעל בני ישראל בקנאו את קנאתי בתוכם ולא כליתי את בני ישראל בקנאתי: לכן אמר הנני נתן לו את בריתי שלום: והיתה לו ולזרעו אחריו ברית כהנת עולם תחת אשר קנא לאלקיו ויכפר על בני ישראל:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses, saying: “Pinhas, the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron the priest, has turned My wrath away from the Israelites, as he was very zealous for My sake among them, and I did not consume the children of Israel in My jealousy. Therefore I say: Behold, I give to him My covenant of peace. And it shall be for him, and his seed after him, a covenant of everlasting priesthood; because he was zealous for his God, and atoned for the Israelites.”

While Pinhas’ fervent action itself is ripe for semiotic analysis, the reward he earns — the covenant of peace — is no less remarkable, as is readily discernible from the biblical text.

One looking inside the text of a Torah scroll at this verse will find the covenant of peace that Pinhas is bequeathed represented somewhat unusually. A vav keti’ah, or a “cut vav,” generally understood to mean a vav sliced down the middle, is included within the word shalom.

A short but enigmatic Talmudic passage (Kiddushin 66b) addresses this disfigured letter:

בעל מום דעבודתו פסולה מנלן? אמר רב יהודה אמר שמואל, דאמר קרא: (במדבר כה) לכן אמור הנני נותן לו את בריתי שלום, כשהוא שלם ולא כשהוא חסר. והא שלום כתיב! אמר רב נחמן: וי”ו דשלום קטיעה היא.

How do we know that the [Temple] service of a [priest] with a blemish is invalid?

Rav Yehudah said Shemuel said, “as the verse said: ‘Therefore I say: Behold, I give to him My covenant of peace (shalom)’ — when he is whole (shalem) and not when he is missing [as is a priest with a blemish].”

But it says “peace” (shalom)?

Rav Nahman said: “The vav of shalom is cut (keti’ah).”

Rav Nahman suggests that the cut vav can effectively be ignored, with the verse then reading shalem (שלם) rather than shalom (שלום). With that emendation, Shemuel can simply assert his interpretation, which defines the priestly covenant discussed in the next verse as pertaining only to those who are whole and disqualifying those with a blemish.

However, an obvious question arises upon reading this passage: Why does the strike-through invalidate the vav? No one says to simply erase that letter, and we still do write out the word shalom, peace, in our Torahs? How can we simply ignore the vav and read shalom as shalem?

Rav Nahman’s appraisal of the vav may bear not just on the form of the letter but to the content matter under discussion as well. It is possible to apply the rule being discussed, the understanding that a bodily blemish renders a priest ineligible for service, to the way that one reads the Torah’s embodied letters. The vav, because it has a slice through its middle, is rendered ineligible to be read; what remains is the word shalem, which in turn reinscribes the teaching that priestly service requires a whole body.

If so, the teaching that a blemished body is invalid appears twice: both in Shemuel’s teaching stemming from the word shalem and in Rav Nahman’s dismissal of the letter vav, which he renders unfit to be read on account of its blemish.

At the same time, however, the vav does still appear in our Torahs, and what is read in shul is shalom rather than shalem; thus the status of the blemished priest can’t be fully clear-cut. While it is clear that Jewish law disqualifies the priest from Temple service — the reasons for which are a conversation for another occasion — the fact remains that a priest, mums and all, retains priestly status in other areas, just as the vav remains an integral part of the Torah.

If we return to our protagonist, the present-but-silent vav keti’ah is the perfect representation of Pinhas’ action. His zealous act damages shalom, by thrusting a spear through the bodies, both literal and literary, in the service of preserving the Jewish people as shalem, whole and safe from plague. Although at some level this produces shalom, the shock of the violent action leaves that peace in pieces.

It is no coincidence that this passage is selected to teach the Halakhah regarding the broken priestly body.

After all, the Pinhas story exemplifies the conception of a broken peace, or at least a broken piece of shalom. Pinhas’ actions — killing Zimri and Cosbi and halting the plague — represent perfectly the theme of peace by destruction, of resolving a breakdown by breaking down the destructive source. Echoing the Talmudic story of Keti’ah bar Shalom, Pinhas’ narrative is also one of achieving peace (shalom) by cutting (keti’ah). Pinhas may attain peace through his intercessive actions, but, to paraphrase another biblical context, it’s a cold and most certainly a broken shalom that is attained.

Significantly, Pinhas’ violent actions are not what one would have expected from a priest. Kohanim stem from Aharon, the quintessential “lover of peace and chaser of peace; one who loves people and brings them close to Torah” (Avot 1:12). But Pinhas’ priesthood, however, is different; indeed it does not stem from Aharon. The Gemara (Zevahim 101b) divulges that, despite being Aharon’s grandson, Pinhas did not originally hold the status of priest. It is only when Pinhas receives a second berit here in verse 13 — the “covenant of everlasting priesthood” — that he is first admitted into the priesthood.

This makes perfect sense, because Pinhas’ priesthood is fundamentally differentiated from Aharon’s, basing its conception of peace not on building community among its members but on zealously cutting out those who do not belong. In doing so, Pinhas manages to stop the plague, indeed achieving peace, but it is a broken peace, represented by the vav keti’ah. As opposed to Aharon’s stopping an earlier plague by offering ketoret (Num. 17:12), Pinhas averts disaster by resorting to violence. His zealotry may have been necessary in the situation, but the peace it yields is of a fundamentally different order, which gives rise to an essentially distinct priesthood from that of Aharon.

In a sense, then, Pinhas is the perfect locus for a discussion of the blemished priest. Pinhas’ priesthood, like a ba’al mum, is blemished, given that it originates with an act of violence. Because it serves a greater goal of securing the Jewish people, it qualifies as shalom, peace, or at least as shalem, the preservation of Israel’s structural integrity. Similarly, on an individual level, the kohen ba’al mum, although lacking in bodily wholeness, still maintains individual integrity and thus remains fundamentally whole, albeit with some ritual limitations.

The word shalom with the vav keti’ah thus occupies the space between brokenness and wholeness; too broken to be fully shalom, but still sufficiently shalem. It symbolizes, visually and semiotically, two distinct, complex tensions facing priests of the peace and piece — both a physically blemished priesthood and the priesthood of Pinhas, bearing his moral blot. Despite their various limitations, we are taught, each can still participate in the covenant of shalom.

The author is very appreciative to Cole Aronson, Tzipporah Machlah Klapper, Elinatan Kupferberg, and Chana Zuckier for their integral editorial contributions to this piece.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.