Hannah Abrams

Yom Kippur marks the end of an 11 week process of working through a tumultuous relationship with God. We mark this time by reading haftarot each Shabbat focusing on the time of year instead of the parashah. The first three weeks pre-empt the destruction of the Temple that we commemorate on Tishah Be-Av, the next seven console us following its destruction, and the final ones address the themes of Yom Kippur. This cycle of haftarot marks out a period of the Jewish year that we rarely think of as a cohesive unit. However, more careful analysis of the progression in these haftarot will bring to light an important facet in the relationship between God and the Jewish people in exile.

The haftarot of the three weeks starting after the 17th of Tammuz and ending with Tishah Be-Av are characterized by harsh rebuke (Jeremiah 1:1-2:3; Jeremiah 2:4-28; Isaiah 1:1-27 “Hazon”). They serve to remind us that the Temple was destroyed due to our own sins and that we have only ourselves to blame. However, Tishah Be-Av itself follows these haftarot, a day of despair on which we feel that the punishment was too severe and that we were abandoned by God. Because Tishah Be-Av is a day of intense religious pain and distance from God, it is followed by seven weeks of haftarot reassuring us through the words of Isaiah that the relationship between God and the Jewish people is not over (Isaiah 40:1-26 “Nahamu”; 49:14-51:3; 54:11-55:5; 51:12-52:12; 54:1-10; 60:1-22; 61:10-63:9). Finally, the cycle concludes with two haftarot of teshuvah: “Dirshu” on Tzom Gedalyah[1] (Isaiah 55:6-56:8) and “Shuvah Yisrael” on “Shabbat Shuvah,” the Shabbat before Yom Kippur (Hosea 14:2-10, Joel 2:11-27). This custom of thematic haftarot is recorded in the Pesikta Rabbati[2] and is cited by Rabbeinu Tam (Tosafot Megillah 31b s.v. Rosh Hodesh) and Rambam in his Mishneh Torah (Hilkhot Tefillah 13:19).

But why do the thematic haftarot have these specific calendrical boundaries? What is significant about the period beginning the week after the 17th of Tammuz and ending the week before Yom Kippur? And how did the haftarot of repentance get grouped together with the other haftarot about the destruction of the Temple?

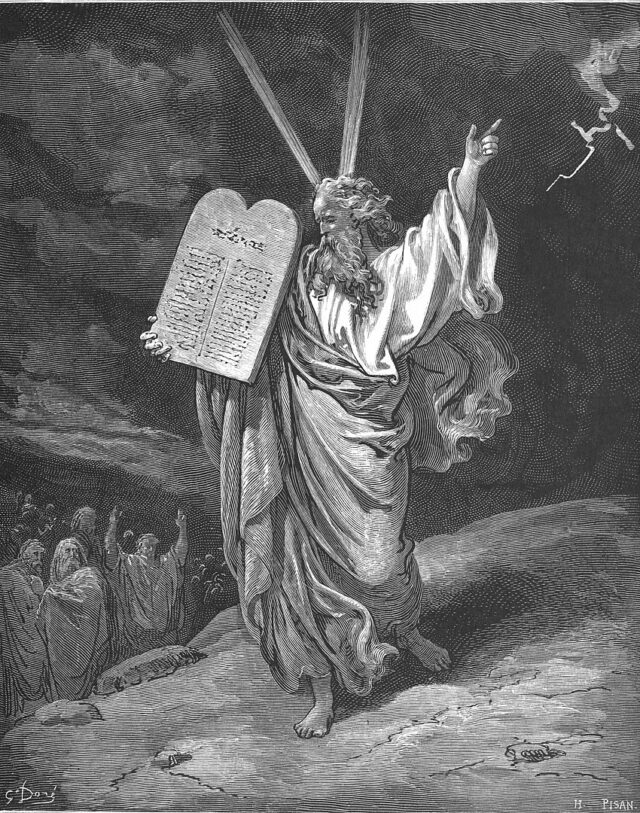

These boundaries evoke a memory for the Jewish people that can shine an important light on our own relationship with God. The Mishnah (Ta’anit 4:6) teaches that on the 17th of Tammuz the first set of tablets were destroyed by Moses in reaction to the sin of the Golden Calf. Later in the chapter (Ta’anit 4:8), the Sages reveal that it was on Yom Kippur that the second tablets were given to us, signaling full forgiveness from God. The Children of Israel abandoned God and His mitzvot when they worshipped the golden calf. God wanted to destroy them completely. Moses acted as an intermediary, initiating a process of reconciliation. He persuaded God that the covenant still stood and that the relationship was not over. God agreed not to destroy the Children of Israel entirely but was still angry with them. Moses then urged the people to repent, and he himself went to beg God for forgiveness on Mount Sinai. God called Moses to the mountain to receive the second set of tablets, also giving him the 13 middot ha-rahamim, or attributes of mercy, as a formula to ensure future forgiveness. The culmination of this process of forgiveness, reconciliation, and redemption took place on Yom Kippur, when Moses descended with the second tablets. This day was so joyful that it was called “the day of His wedding” (ibid.).

Biblically, according to the Mishnah’s timeline, the period between the 17th of Tammuz and Yom Kippur is a period when the Jewish people healed their relationship with God and God forgave them. Thus, at a basic level, the cycle of haftarot delineated by these same calendrical boundaries reminds us to continue to take part in that same process of healing and reconciliation from Tishah Be-Av to Yom Kippur.

But by looking at the texts of these haftarot, we can uncover a different perspective and a message more apropos for our current relationship with God in exile. Let us consider how Abudarham, a fourteenth century commentator on the synagogue liturgy, frames the seven haftarot of consolation.

Abudarham explains that these haftarot are a dialogue between the Jewish people and God, initially mediated by Isaiah.[3] In this framework, the first line of each haftarah represents its theme:

- God tells Isaiah, nahamu nahamu ami – bring comfort to My people.

- But His people reject the comfort offered by Isaiah – va-tomer tziyyon azavani Hashem – Zion says God has abandoned me.

- Isaiah returns to God and says aniyah so’arah lo nuhamah – the poor and persecuted nation refuses to be comforted by me.

- God responds, Anokhi Anokhi Hu menahemkhem – it is I, it is I who consoles them!

- God adds, rani akarah – sing out barren nation, because I am your Husband and will not abandon My wife.

- God then finishes with, kumi ori! – Rise and shine, since all the nations who have persecuted you will flock to honor you.

- Finally, at long last, the Jewish people respond to God’s efforts, sos asis ba-Hashem – I will greatly rejoice in God, for I am His bride.

Note that the Jewish people in this analysis are very picky about the type of comfort that they will accept. They reject Isaiah as an intermediary to give comfort and heal the relationship; they will hear only from God Himself (haftarah #2). They also reject certain formulations of the relationship between God and His people. They do not respond when God speaks only in terms of a nation and its God (#1 and #4). Rather, it’s only when God depicts Himself as a Hatan and the Jewish people as a kallah (#5) that they rejoice in the image of a joyful and powerful nation crowned as the bride of God (#6 and #7).

Examining the words of the haftarot more closely, one can see this process unfold. In the haftarah of rani akarah, God tells His people, “For God has called you, ‘as a wife forsaken and grieved in spirit. And a wife of youth, can she be rejected?’ says your God. For a small moment have I forsaken you, but with great compassion will I gather you.” (Isaiah 54:6-7). Then, in the haftarah of kumi ori, God paints a glorious picture of Israel as the honored nation to which all others will bow down to. Finally, In sos asis, the final of the seven haftarot of consolation, Israel responds directly to these combined ideas:

I will greatly rejoice in the Lord, my soul shall be joyful in my God. For He has clothed me with the garments of salvation, He has covered me with the robe of victory. As a bridegroom puts on a priestly crown, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels. For as the earth brings forth her growth, and as the garden causes the things that are sown in it to spring forth, so the Lord God will cause victory and glory to spring forth before all the nations (Isaiah 61:10-11).

Further on in sos asis, God replies to Israel’s joy in similar terms: “For as a young man marries a young woman, so shall your sons marry you. And as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride, so shall your God rejoice over you.” (Isaiah 62:5).

Read this way, these haftarot identify the terms on which Israel finds comfort in God following the apparent abandonment of Tishah Be-Av. They need to hear that the relationship is intimate and loving, like that of a husband and wife. They need the assurance that their reconciliation will not be muted, but will be as joyful as a wedding day.

Abudarham’s model provides a post-Temple perspective on the process of abandonment and reconciliation that begins with the 17th of Tammuz and concludes with Divine forgiveness on Yom Kippur. In the Torah, following the sin of the Golden Calf, Moses acts as the intermediary between the people and God, putting forward arguments for reconciliation on behalf of the Jewish people. God is difficult to persuade, but in the end forgives His people. However, our own process of reconciliation following Tishah Be-Av is quite different. As explained in Aburdarham’s analysis of the haftarot, we now reject any intermediary. We insist on intimacy; we must have a direct conversation with God. Moreover, this time around, it is God putting forward arguments for reconciliation. We are the ones who need persuading.

What is the difference between these two stories of sin and reconciliation? Why has the relationship shifted? Perhaps in a world absent obvious connection with God, without miracles like the Red Sea and without the constant of the Divine Presence—the shekhinah—in our midst, we need an explicit promise to remind us that God is still close. In our world darkened by hester panim, by a shadowing of God’s presence, it feels like the burden of proof has shifted. It is God who must prove that He is still with us, and that He is present with the closeness of a bridegroom to His bride.

Leading up to Yom Kippur, we sometimes feel the weight of our relationship with God resting entirely on our shoulders. It is our job to repent, to draw close to God. That is true, but these haftarot remind us that the onus of the relationship is not entirely on us. For the last few weeks God has been actively comforting us, assuring us of His forgiveness and promising us redemption. God is closer to us now, more intimate than ever.The model of our relationship is that of husband and wife, a more equal partnership, where both sides bear responsibility for the relationship. Rashi (Deuteronomy 30:3) explains that the shekhinah dwells with us in exile, and that it is together, hand in Hand, that we will achieve redemption.

Recall that the two haftarot of teshuvah (Dirshu and Shuvah) are appended to the end of the seven haftarot of consolation. Following a break in our relationship with God raising the existential questions of exile, punishment, and abandonment, we take seven weeks to heal the relationship. It is only after we understand that God still cares for us and we have forgiven Him for how He has punished us that we can return to Him in teshuvah. Yom Kippur is the culmination of a process of mutual forgiveness. We cannot beg God to forgive us when we still need to forgive God.

Once we have understood that God has done His part in comforting us and promising us forgiveness, then we will realize that we must do our part too. We enter Yom Kippur with the knowledge that God has brought Himself close to us. It is now up to us to bring ourselves close to Him and receive His forgiveness.

[1] The haftarah of Dirshu is read on all fast days, not just Tzom Gedalyah. However, the Pesikta Rabbati includes it in the cycle of haftarot connected to Tishah Be-Av.

[2] The Pesikta Rabbati is a late midrashic collection on the parashah and haftarot. The part of the Pesikta addressing the thematic haftarot is quoted in Tur Orah Hayyim 428:8.

[3] Sefer Abudarham, Seder ha-Parshiot v-haHaftarot.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.