Eli Rubin

Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brothers also to dwell together!

(הִנֵּ֣ה מַה־טּ֖וֹב וּמַה־נָּעִ֑ים שֶׁ֖בֶת אַחִ֣ים גַּם־יָֽחַד: (תהלים קלג:א

The appearance of the Hebrew word גַּם as the penultimate word in this verse makes an accurate translation especially awkward. But even in its original language this word indicates that something additional and yet unmentioned is being celebrated, besides for the dwelling of brothers together. In several places in the Zohar this is interpreted to refer to G-d. When people dwell together as brothers, G-d “also” dwells with them in harmony; when “G-d” dwells among us, we “also” dwell together as brothers.

We currently inhabit a moment when it seems that nature has conspired to isolate us from one another. The world is suffering from illness. All of us are suffering from isolation. The implication of the Zohar is at once poignant and comforting, comforting and poignant; G-d is also in isolation.

Each year, Lag ba-Omer is celebrated as the “yahrtzeit” or “hillula” of the Zohar’s hero, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (“Rashbi”). The following passage was often cited and discussed by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, as an illustration of the transformative power of Rashbi’s Torah, and of its significance in our own service of G-d.

This year, it reads with particular resonance:

One time, the world needed rain. Rabbi Yeisa, Rabbi Hizkiyah, and other members of the fellowship came before Rabbi Shimon. They encountered him as he was on the way to visit Rabbi Pinhos ben Ya’ir, together with Rabbi Elazar his son. As soon as he saw them, he opened and spoke:

“A song of ascents … Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brothers also to dwell together.” This is as it is said, “and their faces each toward the other” (Exodus 25:20). Of the time when they are one to one, gazing into each other’s faces, it is written “how good and pleasant!” And when the male turns his gaze away from the female, woe to the world! And of this it is written, “and some perish without justice” (Proverbs 13:23). Certainly, without justice, and it is written “righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne” (Psalms 89:15), meaning that one cannot go without the other. When justice becomes distant from righteousness, woe to the world! And now I have seen that you have come because the male does not dwell with the female.

Said Rabbi Shimon:

If it is for that reason that you have come to me, you may return. For on this day I have looked and seen that all is returning to dwell face to face. And if you have come to hear Torah, remain with me.

They said to him:

It is for everything that we came before the master. One of us will depart to tell the good news to our brothers, the rest of the fellowship, and we will sit before the master.

Before they departed, he opened and spoke:

“I am dark and beautiful, O daughters of Jerusalem, etc.” (Song of Songs 1:5). Said the Congregation of Israel before the Holy One, blessed be He, “In the exile I am dark, but with the commandments of the Torah I am beautiful; for although the Jewish people are in exile, they do not abandon the commandments.”

… “My mother’s sons quarreled with me” (Song of Songs 1:6) … Of this it was certainly said “behold how good and how pleasant it is for brothers also to dwell together” … This refers to the fellowship, when they sit as one, and are not separated one from the other. At the outset, [when engaged in Torah debates,] they appear as warriors at war, as if they want to kill one another. Afterwards, they return to one another with the love of brothers. What does the Holy One, blessed be He, then say? “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brothers also to dwell together.” The additional word “also” includes among them the indwelling of the divine (shekhinta). And more so! The Holy One, blessed be He, listens to their words [of Torah], and it is pleasant for Him, and He takes joy in them. This is the meaning of the verse, “then shall those who fear G-d speak, one to his fellow, and G-d shall listen and hear, and a scroll of remembrance shall be written before Him etc. (Malakhi 3:16).

And you, the fellows who are here, to the same degree that you have cherished one another with love prior to now, so too, from now and onwards, you shall not separate one from the other. Then the Holy One, blessed be He, will take joy in you and draw peace upon you. And in your merit peace will settle upon the world. This is the meaning of the verse, “For the sake of my brothers and friends; I shall speak, beseeching peace among you” (Psalms 122:8).[1]

Characteristically, the Zohar’s profound mix of lyrical narrative and rich exegesis brings its lofty message into the concrete reality of embodied life.

Of course, there are many prisms through which to parse the meaning of this passage, with layer upon layer of significance waiting to be discovered. Here I will not attempt to explain each detail and nuance, and will leave the reader to probe the different dimensions of this zoharic story and the teachings it contains.

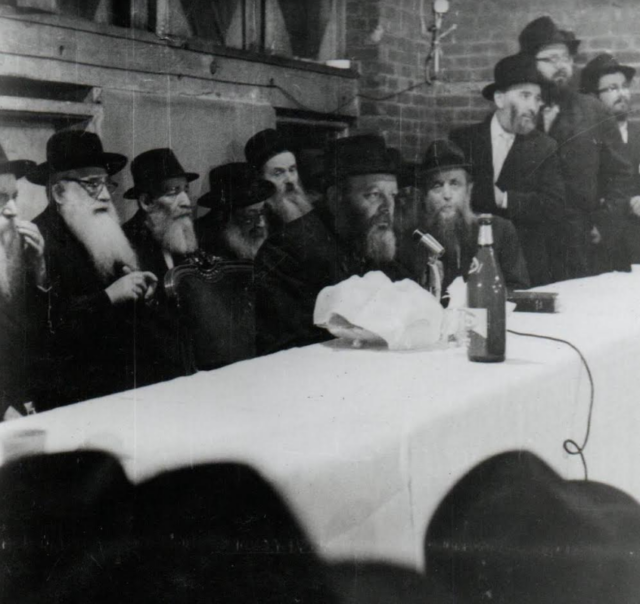

On Lag ba-Omer in the year 1962, the Lubavitcher Rebbe delivered a set of informal talks on the unique revelation embodied by the Torah of Rashbi, followed by a formal discourse that brings the significance of the above passage into sharp focus. The following reflections are based on that discourse, as edited and published in 1990.[2] A recording of the original audio can be heard here.

* * *

In the Zohar’s account, as translated above, Rashbi preempts a request to pray for rain with a Torah teaching about the intertwining of the horizontal relationship between human beings and the vertical relationship between human beings and G-d. Thereby, Rashbi contextualized the occurrence of a natural disaster—in this case a drought—within that larger matrix of social and spiritual reality.

From this perspective, a natural disaster cannot properly be understood, and we cannot properly respond to it, without taking stock of what it signifies for the way that we each interact with our fellow human beings, and for the way that interaction is further reflected in the union of G-d within the cosmos.

What is it that binds individuals one to another? What is it that creates a community, a society, a dwelling of brothers “also” together? What is it that makes us beautiful even when our situation is dark? What is it that brings repair, healing and peace to the world?

Torah.

It is Torah that binds us together. It is Torah that creates community. It is Torah that makes us beautiful when our situation is dark. It is Torah that brings repair, healing, and peace to the world.

This is the Torah that Rashbi taught. And in teaching this Torah he also enacted it, eliciting rain to end the drought that had parched the world.

* * *

Rashbi’s teaching is not only Torah, but also a reconfiguration of Torah.

Ordinarily, Torah is likened to water, which flows downwards from on high (cf. Taanit 7b). Torah reveals the wisdom and will of G-d to humankind, and thereby dictates the path by which we live out our days upon this earth. Indeed, the Torah’s account of its own giving, of matan torah, begins with the words “and G-d descended upon Mt. Sinai” (Exodus 19:20).

Yet here the living waters of Torah flow upward as well as downward. In both affect and effect, Rashbi’s teaching takes on the quality of prayer; his Torah interpretation intercedes on high and reshapes earthly reality.

In prayer we turn to G-d and plead, “may the desire arise before You, G-d … ” That is, we seek to elicit a new desire. We do not simply seek to affirm or draw forth blessing that G-d has already assigned us. But we seek to intercede, to intervene, to change the course of events as they have previously been prescribed. To pray, therefore, is to exceed the ordinary boundaries that circumscribe existence, to exceed nature and creation, to exceed reason, and to elicit the boundlessness of G-d’s true infinitude.

Torah, by contrast, is divine wisdom. In the Torah G-d’s will is circumscribed and extended into the bounds of created existence; the Torah itself operates and applies law according to clear principles of logic. But in this case Rashbi’s Torah teaching did not provide any logical argument as to why the world deserved rain. On the contrary, it seems that he affirmed the world’s unworthiness: “When the male turns his gaze away from the female, woe to the world! … And now I have seen that you have come because the male does not dwell with the female.” And yet, in the very next line, Rashbi announces that the crisis is already over: “I have looked and seen that all is returning to dwell face to face.”

How is it that Rashbi’s Torah exceeded the boundaries of its own logic and took on the transformative efficacy of prayer? This is possible only because the Torah of Rashbi is more than the revelation of divine wisdom and will, because the Torah of Rashbi is the revelation of G-d’s boundless infinitude within the finite world.

Rashbi’s Torah reconciles opposites. Rashbi’s Torah reconciles heaven and earth, male and female. Through Rashbi’s Torah miracles coincide with nature.

Rashbi did not need to pray for reconciliation, whether between one person and another or between heaven and earth. His Torah itself enacted that reconciliation. In the Rebbe’s words:

Torah [revelation from on high] and prayer [the service of humankind] are two distinct phenomena [each one with its own advantage] only on the station of the souls as their existence becomes distinct from that of G-d. But on the part of the root of the souls, as they are rooted in the divine essence, no distinction can be made between that which flows from above and that which is the service of humankind, for Israel and the Holy One are entirely one. This is revealed in the inner dimension of the Torah, the Torah of Rashbi, and therefore the Torah of Rashbi also encompasses the phenomenon of prayer.[3]

Rashbi’s path of Torah, the Rebbe emphasized, provides each of us with a course to follow in our own lives:

It is incumbent on a Jew that he shall set his life, and his relationship with the world around him, in such a manner that “brothers also dwell together,” meaning that the path of miracles coincides with the path of nature.[4]

These are profound words to be pondered, especially in our current moment of crisis. For the Rebbe, miracles and nature, divine intervention and human work, are not at odds, but must ultimately be understood as a single phenomenon; nature provides the vessel through which miracles are received. To separate miracles from nature, on the other hand, is to isolate G-d from the world.

Rashbi’s Torah—as transcribed in the Zohar and continuously refracted through the revelatory teachings of subsequent masters of Kabbalah and Hassidut—provides an interpretive and cosmological prism through which to transform isolation into togetherness, revealing the infinite within the finite and the miraculous within nature. Through this prism we come to see our place in the cosmos differently; our relationships with the world, with other people, and with G-d acquire new breadth and new depth. All our actions and interactions, including our prayer and our Torah study, are likewise endowed with a quality that contains multitudes.

This is the kind of Torah that we need today: Torah with which we can raise ourselves from the lowest depths precisely because it reveals to us the loftiest heights; Torah with which we can transform the world from within because it reveals nature’s essence to be utterly transcendent.

Just as the Torah of Rashbi brought rain to the world in his own time, so may it bring healing to the world in our time.

[1] Zohar III, 59b.

[2] Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, Kuntras Lag ba-Omer 5750; also published in Torat Menahem – Sefer ha-Ma’amarim Melukat, Vol. 3 (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publication Society, 2012), 270-275.

[3] Ibid., parentheses are in the original text.

[4] This quote is from the talk delivered prior to the formal discourse. For the transcript see, Sihos Kodesh 5722, page 466. For a Hebrew language translation of an edited transcript of the talks delivered during the course of this farbrengen, click here .

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.