For many, Talmud Yerushalmi is an unfamiliar and underappreciated text. Most do not know of the gems that lie underneath its surface. Like the treasures of an ancient shipwreck in the murky deep, Yerushalmi has sat unattended. Even with the advent of commentaries in the modern age, it has mostly remained a closed book, read by a select few.

But this reality is quickly changing. Recently, a student of mine asked me if the city of Lod appeared in Tanakh. I was familiar with a Gemara (Bavli Megillah 4a) that identifies Lod, Ono, and Gei Ha-Harashim as walled cities at the time of Joshua. Not recalling the exact location, I typed the words “Lod Ono” into Sefaria’s search engine. In addition to that source, the sixth search result from Yerushalmi Megillah (1:1) contained interesting information about Lod, so I encouraged my student to look into the passage.

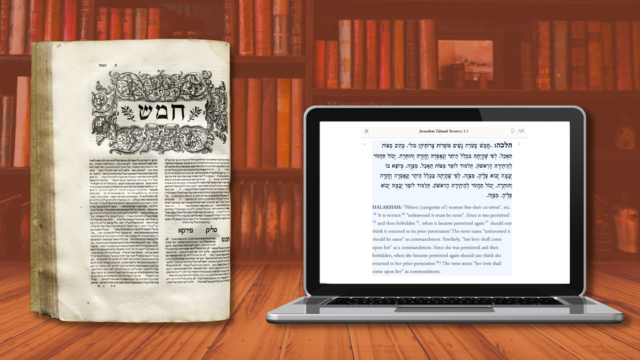

I then realized that I was casually directing a high school student to learn Yerushalmi on her own, something that would have been unthinkable only a few years ago. Moreover, Yerushalmi had entered our Beit Midrash with the ease of a quick word search. Yerushalmi is no longer restricted to the select few able and interested enough to pursue it. Sefaria’s new digital edition of the late Dr. Heinrich Guggenheimer’s translation of Yerushalmi is a watershed moment in history. Now, Yerushalmi can and will have a place in the cultural conversation of the average member of the Beit Midrash. While it remains a difficult text even in translation, its newfound accessibility is unprecedented in history.

This article aims to introduce Yerushalmi to a wider audience. It focuses on two themes. Firstly, after a brief historical overview, I will establish the value of studying Yerushalmi. Not only does it contain unique traditions not preserved in Bavli, but it offers fruitful comparisons to parallel passages common to the two texts. Secondly, I will survey the larger reception history of Yerushalmi. The persistent obscurity of the text throughout Jewish intellectual history, even through the twentieth century, highlights the significance of today’s widespread accessibility.

Origins

Most commonly known as the Talmud Yerushalmi (Jerusalem Talmud), the text is also known as Talmud Eretz Yisrael (Talmud of the Land of Israel), Talmuda de-B’nei Ma’arava (Talmud of the Westerners), and the Palestinian Talmud (especially in academic

circles).[1] Despite its name, the anonymous editors did not compose the text in Jerusalem, then a non-Jewish city known as Aelia Capitolina. Rather, the composition took place in the Galilee, primarily in Tiberias as well as other locations.[2]

Yerushalmi is the compilation of seven generations of Amoraic scholars over a roughly 200-year period from 225-425 CE. Some scholars have assumed an earlier date for the completion of Yerushalmi, around 375 CE; not long after the Gallus revolt of 351 and the earthquake in the Galilee twelve years later.[3] R. Aharon Heiman, for instance, assumed that the Yeshivot of Eretz Yisrael were destroyed during the suppression of this revolt and that most of the Amoraim traveled to Bavel.[4] However, Hillel Newman has pointed to evidence that Rabbi Mana, the most influential Amora of the fifth generation, remained active into the 380s.[5] Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 3:5 records that Rabbi Mana instructed the bakers of Sepphoris to bake bread when a certain Proqla arrived. Newman identifies this Proqla with Proculus, a prefect of Constantinople, who governed Palestine in c. 380. Also, Gamliel VI was demoted from his position of Nasi in 415, and Theodosius had already abolished the institution by 429.[6] It is likely that the compilation of Yerushalmi was completed sometime around then, whether or not the ending of the Patriarchate directly contributed to it.[7]

Unique Yerushalmi Traditions

Comparing Yerushalmi to its more famous counterpart, the Talmud Bavli (Babylonian Talmud), the most obvious difference concerns what sections of the Mishnah each focuses on. Yerushalmi comments on all of the order of Zera’im, while Bavli, composed outside of Israel where the issues of Zera’im are less practical, only comments on Berakhot. The reverse is true for Seder Kodashim, for which only Bavli exists. Yerushalmi also comments on Tractate Shekalim of Seder Moed, which Bavli skips.[8] Additionally, there is no gemara in our versions of Yerushalmi on the last four chapters of Shabbat, the last chapter of Makkot, and the last six and a half chapters of Niddah. Yerushalmi probably had commentary on these chapters at one point, but they were likely lost before the Middle Ages.[9] Thus, Yerushalmi offers the unique opportunity to study an additional eleven tractates of Gemara on Zera’im and Shekalim.

Moreover, Yerushalmi preserves hundreds of Tannaitic and Amoraic traditions absent in Bavli. Bavli contains many more statements from the first four generations of Eretz Yisrael Amoraim, but much less material from the fifth generation and onward. For example, while Bavli Ta’anit (23b) relates several stories about the above-mentioned Rabbi Mana (or Mani in Bavli), it barely discusses his halakhic opinions; in Yerushalmi, on the other hand, he appears regularly throughout. In Bavli, Rabbi Mani’s father Rabbi Yonah, and the latter’s contemporary Rabbi Yose bar Zavda, the leaders of the Amoraim of the fourth generation in Eretz Yisrael, appear only occasionally. But in Yerushalmi, Rabbi Yonah dominates halakhic discussions, especially in Seder Zera’im, and Rabbi Yose appears numerous times.[10] Somewhat surprisingly, this phenomenon occurs even for Babylonian Amoraim. Y. Florsheim has noted a number of opinions of the Babylonian Amora Rav Hisda that only appear in Yerushalmi.[11] Amoraim who appear only in Yerushalmi are no less valuable than Bavli opinions we do not follow in halakhic practice.

Comparing Bavli and Yerushalmi

The above remarks concern traditions not shared by the two corpora. But the numerous traditions common to both Talmuds present a rich opportunity for direct comparison. As Ritva wrote, “We always rely on their Talmud (i.e. Yerushalmi) and interpret and codify our Talmud (the Bavli) based on their (the scholars of Yerushalmi) words.”[12]

For example, Bavli Shabbat 17a obliquely relates that during the debates over the eighteen decrees between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, a sword was struck in the Beit Midrash. Yerushalmi Shabbat 1:4, however, preserves the astonishing testimony that students from Beit Shammai murdered members of Beit Hillel![13] Another fascinating example concerns yibbum (Levirate marriage). Bavli Yevamot 39b relates the opinion of Abba Shaul that performing yibbum for impure motives is akin to ervah (forbidden relations). Accordingly, without the proper intentions, halitzah (dissolution of the Levirate bond) is preferable. Fascinatingly, Yerushalmi Yevamot 1:1 notes that the Tanna R’ Yose adhered to the opinion of Abba Shaul; he had intercourse with his yevamah (late brother’s wife) through a sheet, implying that reducing pleasure facilitates more pure intentions for the act. These examples deepen our understanding of Bavli traditions.

Beyond these two curious examples, one may consult the groundbreaking works of Rabbi Ahikam Kashat: Amrei Be-Ma’arava and Darkhei Ha-Talmudim. The former lists thousands of individual differences between Bavli and Yerushalmi, organized by tractate. The latter systematically analyzes, over the course of more than five hundred pages, 121 fundamental differences between the two Talmuds. Amrei Be-Ma’arava is an excellent work for a student of Bavli who wants to see novel points in Yerushalmi on any sugya. The same work also has helpful indices that list, in Kashat’s opinion, the major novellae of Yerushalmi in both Halakhah and Aggadah (numbering, respectively, 160 and 95). Additionally, it contains an index of 114 points of normative Halakhah derived from Yerushalmi. Thus, to properly understand Bavli, as well as many of our religious traditions, we must also study Yerushalmi. Thankfully, doing so is now easier than ever before.

Yerushalmi in the Middle Ages

We know very little about what happened to Yerushalmi for the first 500 years after its completion. Unlike the Babylonian Talmud, about which we have the rich letter of Rav Sherira Gaon (987), we have barely any information about the nature of learning in the land of Israel in late antiquity. The oldest extant piece of Yerushalmi is a seventh-century synagogue mosaic in Rehob, near Beit She’an. The document contains the Beraita de-Tehumin, the list of the borders of the land of Israel found in Yerushalmi Shevi’it (6:1), and a selection from Yerushalmi Demai (2:1). It indicates that some communities used Yerushalmi as a source of Halakhah in this period.[14]

Another cryptic source appears in Seder Olam Zutta (end of chapter 10), which recounts that Mar Zutra fled Babylonia in 520 and became Reish Pirka (a head of yeshiva). It then provides a list of his successors up to 804.[15] Did Mar Zutra and the following Reishei Pirka study Bavli, Yerushalmi, or both? We simply do not know. In around 800, Pirqoi Ben Baboy wrote that scholars from Eretz Yisrael had traveled to the West with parts of Talmud in Seder Nashim, implicitly of Yerushalmi.[16] Interestingly, several Karaite sources indicate that some form of a commentary and/or abridgement of Yerushalmi existed.[17]

The information in later periods is not much clearer. Even from the beginning of the eleventh century, when records from the Genizah exist, we do not know how exactly the scholars of Eretz Yisrael valued Yerushalmi. It is clear by that point that they had already adopted Bavli as authoritative alongside Yerushalmi. We even know that Yahya, the son of the Gaon of Jerusalem Shlomo ben Yehudah (d. 1051), learned Halakhot Gedolot under Rav Hayya Gaon in Baghdad.[18] Yerushalmi was certainly available; fragments of Yerushalmi dated to circa 900 have survived from the Genizah. However, we do not know whether the Rabbis of Eretz Yisrael would have decided the Halakhah in favor of Yerushalmi over the Bavli.[19]

A Genizah fragment of the beginning of Bavli Berakhot (L.G. Misc. 36) provides an interesting clue. This copy belonged to children of a member of Haburat Eretz Ha-Tzvi, the senior Palestinian Rabbinic committee composed of seven scholars. The scribe lists the title of the book as Berakhot Talmud Shel Anshei Mizrah, “Berakhot [of the] Talmud of the People of the East” (i.e. Babylonia), which echoes the similar appellation for Yerushalmi Talmuda de-B’nei Ma’arava (often contrasted with Talmud Didan, “our Talmud,” for Bavli). The scribe’s usage of the term Shel Anshei Mizrah implies that he did not see Bavli as his own Talmud, but rather Yerushalmi.

Concerning the Geonim of Bavel, Robert Brody concluded that the Yerushalmi was either unknown or ignored before the period of Saadia Gaon, who was active in the first quarter of the tenth century.[20] After Saadia Gaon, usage of Yerushalmi increased, especially in the writings of Sherira Gaon and his son Hayya Gaon. Even so, one could read through the entire letter of Rav Sherira Gaon about the history of Torah learning and not realize that Yerushalmi even existed![21] In a similar vein, Hayya Gaon explicitly declared that Halakhah should follow Bavli over Yerushalmi.[22]

The next extensive use of Yerushalmi appears in the writings of Rabbeinu Hananel and Rav Nissim Gaon, both active in the first half of the eleventh century in Qayrawan, Tunisia. They quote Yerushalmi hundreds of times in their commentaries on Bavli. It is not clear why specifically at that time Yerushalmi gained popularity, as Yerushalmi was seemingly not well known in Qayrawan before then.[23] Some have conjectured that Rav Hushiel, the father of Rabbeinu Hananel, may have brought

the Yerushalmi to Qayrawan.[24]

Yerushalmi’s further spread occurred gradually. For example, Rashi seemingly did not have access to a full copy of Yerushalmi, while Rabbeinu Tam had at least a copy of Yerushalmi Zera’im and Moed in his library.[25] Even the Rishonim most interested in Yerushalmi struggled to find copies of it.[26] Ri could only look up something in Yerushalmi Avodah Zarah after gaining access to a copy,[27] Ra’avyah wrote that he does not have access to Yerushalmi Kilayim,[28] and Ra’avad lamented that the Yerushalmi we possess was not properly edited.[29] About 100 years later, Rashba attributes the gross errors in Yerushalmi to the lack of study; only one in a generation masters it (omeid alav). The above comments came from Rishonim who quoted Yerushalmi extensively and studied it regularly. So many others had no interest in or awareness of Yerushalmi.

In contrast, among the Rishonim who did study Yerushalmi extensively was Rabbi Shimshon of Shantz (Sens), who used Yerushalmi throughout his commentary on Mishnah. Rambam, who based many rulings in Mishneh Torah on Yerushalmi, wrote that he had plans to write a summary of the practical halakhot derived from Yerushalmi, like Rif did for Bavli. It seems he eventually abandoned this project, but some of this work in Rambam’s handwriting survived in the Genizah.[30] Additionally, a student of Ra’avad, Rav Yitzhak Cohen, wrote a commentary on most of the three orders of Moed, Nashim, and Nezikin.[31] Rabbi Yehudah ben Yakar, the teacher of Ramban, also apparently authored a commentary on Yerushalmi.[32] Unfortunately, neither of these texts have survived. Unlike the rest of Yerushalmi, several medieval commentaries on Tractate Shekalim have survived.[33] For the most part, Yerushalmi remained obscure throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. I would estimate that at any given time during the Middle Ages, no more than about 100 people studied Yerushalmi regularly.

Early Modern Yerushalmi

The advent of the printing press did not totally alter Yerushalmi’s obscurity. The first printing of Yerushalmi occurred in Venice in 1523. By the time of the second printing in Cracow in 1609, the publisher noted that “only one in a city and two from a family” (Jeremiah 3:14) have a copy of Yerushalmi. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, complaints of scarcity continued.[34]

Even those who could obtain a copy of Yerushalmi faced the daunting task of learning this difficult text without a commentary. Rabbi Shlomo Sirilio (1485-1554) sought to rectify this situation by authoring a commentary on Zera’im and tractate Shekalim, though he did not succeed in printing his work (it was later published, beginning with Shekalim in 1875). The same occurred for other contemporaries, such as Rabbi Elazar Azkiri (1553-1600, author of Sefer Hareidim), whose commentaries on Yerushalmi Berakhot and Beitzah were only published in the twentieth century. R. Yehoshua Beneviste (1590-1665) wrote a commentary called Sadeh Yehoshua on eighteen tractates of Yerushalmi, but only the commentary on four tractates of Zera’im was published in his lifetime; the others waited until 1749. The 1609 Cracow edition of Yerushalmi contains the exceptionally brief commentary of R. David Darshan, fittingly known as Perush ha-Katzar (“the short commentary”) which is not a line-by-line elucidation.

Over the first half of the eighteenth century, the commentary of R. Eliyahu of Fulda (c. 1650-c. 1720) to Zera’im, Shekalim, and the three Bavas, was published piecemeal. After his death, his project was continued by R. David Fraenkel (c. 1704-1762), who died having nearly finished and published a commentary named Korban Ha-Eidah on the remaining sections of Yerushalmi (his commentary is missing for the end of Seder Nezikin and tractate Niddah). At the same time, R. Moshe Margolis (1710-1781) accomplished the feat of writing the first complete commentary, Pnei Moshe.[35] However, only half of his commentary appeared during his lifetime; it was first fully printed in the Zhitomir edition of the Talmud (1860-1867), alongside Korban Ha-Eidah. Thus, before 1867, no one had access to a full commentary of Yerushalmi in one edition.[36] The barriers to entry remained enormous.

Modern Yerushalmi Studies

The first academic work devoted to Yerushalmi was Mevo Le-Yerushalmi (1870) by R. Zacharias Frankel. Despite the passage of time, his work remains important. In 1909, Professor Louis Ginzberg published Seridei Yerushalmi, a large collection of Genizah fragments of Yerushalmi and variant readings from the Vatican manuscript of Zera’im and Sotah. Concurrently, Ber Ratner of Vilna published Ahavat Zion Ve-Yerushalayim, collecting the quotes of Yerushalmi found in Rishonim. Ratner died in 1917 in the middle of his work. Several scholars, most recently Yaacov Sussman and Moshe Pinchuk, have continued his project, and the latter maintains an online database of all the references. Ginzberg also published a three volume commentary on Yerushalmi Berakhot with a scholarly introduction. Yaakov Nahum Epstein, the father of modern academic Talmud studies, wrote important articles and introductions to Yerushalmi.[37] His student Saul Lieberman wrote several groundbreaking articles as well as a commentary on a number of tractates.[38]

In the twenty-first century, the Academy of Hebrew Language published an academic edition of Yerushalmi based on the Leiden manuscript (the only complete manuscript of Yerushalmi) and all other manuscripts, under the direction of Yaacov Sussman and Binyamin Elizur.[39] Also noteworthy is Professor Leib Moscovitz’s Terminology of Yerushalmi, which systematically discusses hundreds of phrases of Yerushalmi.

Beyond studies specific to Yerushalmi, the comparative analysis of Bavli and Yerushalmi is the bread and butter of academic Talmud studies. Without Yerushalmi, it would be much more difficult to untangle the complex layers of transmission and editing found in Bavli. It is axiomatic that any academic study of Bavli must include relevant analysis of Yerushalmi.[40]

Popular Interest

Within recent history, the first large-scale study initiative of Yerushalmi began with the creation of the Daf Yomi Yerushalmi by the fifth Rebbe of Ger in 1980. Several easy-to-use commentaries written by Ger Chassidim have since appeared on the market.[41] Artscroll’s publication of Yerushalmi, begun in 2005 and one tractate away from completion, has also increased public interest and accessibility.[42] In Israel, Machon Orot Ha-Yerushalmi, run by Rabbi Avraham Blass, is devoted to promoting Yerushalmi amongst the public. The organization is producing its own commentary on Yerushalmi, Or La-Yesharim, authored by Rabbi Yehoshua Buch.

The Internet has provided new opportunities for the study of Yerushalmi. Shiurim on the entire Yerushalmi in multiple languages are available on YUTorah and Kol Ha-Lashon.[43] Prof. Guggenheimer’s commentary was originally made public by his publisher, DeGruyter, on their website in a PDF version. ALHATORAH and Sefaria have now both integrated this commentary into their respective databases, allowing for full search of Yerushalmi. Significantly, Guggenheimer’s text is almost entirely based on the Leiden manuscript, infinitely superior to the standard 1922 Vilna edition.[44] Sefaria has also added the French translation of Moïse Schwab and links to images of the Leiden manuscript and the first printed edition. Sefaria’s user-friendly interface—which includes intertextual connections—as well as its handy source sheet creator will facilitate the inclusion of Yerushalmi in many future lectures and classrooms.

The Internet has democratized learning, removing so many barriers to entry for the layperson. Astonishingly, we are witnessing the opening up of a text that was for most of its history not easily accessible, even for the scholarly elite. Yerushalmi has now transformed from a text marginalized by the Geonim to one learned by thousands, from a text difficult to obtain to one easily at our fingertips. In so many ways, it is remarkable that we did not lose Yerushalmi over the past 1600 years. I look forward to a great future as the wider world begins to learn and appreciate the light of Yerushalmi.

[15] This date appears explicitly in some manuscripts, but not in the version on Sefaria.

[16] Genizah fragment L-G Talm. 1-20; this is the correct reading of the fragment, and not genuzin, hidden, in place of Nashim (to access Genizah documents cited in this essay, readers may create a free account here).

[17] Salman ben Yeroham, a ninth-century Karaite, in his commentary on Psalms 140:6, criticized Saadia Gaon for denying that bloodshed occurred between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, stating that he sent the Yerushalmi noted above (Shabbat 1:4) with the commentary of Yaakov ben Ephraim al-Shami to Iraq to publicize Saadia’s “cover-up”. It is possible to read Salman’s comments as referring to a (at least partial) commentary on Yerushalmi, which would be the earliest known example. For more about Yaakov ben Ephraim al-Shami, see the addendum here, which also contains a transcript and translation of Salman’s comments. Also, Lieberman (here, p. 2) quotes eleventh-century Karaite scholar Yeshua ben Yehudah’s testimony that he saw an abridged version of Bavli and Yerushalmi. Lieberman believes this is a reference to Sefer Metivot, a lost work from the Gaonic period, quoted primarily by Yitzhak ben Abba Mari (author of Sefer Ha-Ittur).

[19] For an overview of the Torah of Eretz Yisrael after the completion of Yerushalmi, see here.

[21] Sussman emphasizes this point. See “Before and After the Leiden Manuscript of the Talmud Yerushalmi,” p. 204.

[22] Otzar Ha-Geonim, Pesahim, no. 39.

[24] Rav Hushiel came from Italy, an area within the sphere of influence of the Eretz Yisrael Yeshiva, and he was the teacher of Rav Natan, Av Beit Din of that Yeshiva. See M. Gil, Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 177-180.

[26] See Sussman “Before and After the Leiden Manuscript of the Talmud Yerushalmi,” ; further quotes from Rishonim are from there.

[37] Interestingly, in a letter, Saul Lieberman defended Epstein against criticism from his cousin Hazon Ish. Lieberman stated that Epstein’s methods helped him understand many obscure passages in Yerushalmi. See Genazim u-She’elot u-Teshuvot Hazon Ish, pp. 207-209 (referenced here).

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.