Shloime Schwartz

I. Introduction: The Journey of Repentance

The story of Rabbi Elazar ben Dordaya (from here on abbreviated as REBD), related on Avodah Zarah 17a, is one of the more well known stories in the Talmud. Its themes of redemption, repentance, and the value of a single moment make it a perennial classic, especially during the High Holidays, when introspection and thoughts of change are on everyone’s minds. A theme that is returned to year after year is that teshuvah is more than just settling spiritual debts; it is an odyssey of return for the weary soul that has wandered far from its home. It is this spiritual journey that is exemplified in the story of REBD.

I was drawn to a deeper study of this story not only because of its powerful central ideas, but also because of the astonishing amount of questions it raises. As I looked in the commentaries for answers to these questions, the saga of REBD crystallized for me into more than just a story: it was a treasure trove of insight into some of the fundamental ideas of Judaism.

I present here a synopsis of some of the commentaries on the REBD narrative and the key themes that emerge. The sheer variety and volume of material is beyond the scope of a short essay, but I hope the summarized information incorporated here can at least convey a sense of the depth and inspiration that our greatest sages found in this story.

II. Avodah Zarah 17a: “Rabbi Elazar ben Dordaya is destined for life in the World-to-Come”

To understand the story, it needs to be seen in full, and with some context. The Gemara had been discussing the sin of idol worship. It was stated that due to the severity of this sin, someone who worshipped idols and wished to repent would have to die as part of the teshuvah process. The story of REBD is mentioned to challenge the idea that idol worship is the only sin for which death is a necessary part of repentance:

“[The Gemara asks:] And is it correct that one who repents of the sin of forbidden sexual intercourse does not need to die? But isn’t it taught in a Baraita: They said about Rabbi Elazar ben Dordaya that he did not leave one prostitute in the world with whom he was not intimate. Once, he heard that there was one prostitute in one of the cities overseas who would take a purse full of dinars as her payment. He took a purse full of dinars and went and crossed seven rivers to reach her. When they were engaged in the matters to which they were accustomed, she passed wind and said: Just as this passed wind will not return to its place, so too Elazar ben Dordaya will not be accepted in repentance.

Elazar ben Dordaya went and sat between two mountains and hills and said: Mountains and hills, pray for mercy on my behalf. They said to him: Before we pray for mercy on your behalf, we must pray for mercy on our own behalf, as it is stated: “For the mountains may depart, and the hills be removed” (Isaiah 54:10). He said: Heaven and earth, pray for mercy on my behalf. They said to him: Before we pray for mercy on your behalf, we must pray for mercy on our own behalf, as it is stated: “For the heavens shall vanish away like smoke, and the earth shall wax old like a garment” (Isaiah 51:6). He said: Sun and moon, pray for mercy on my behalf. They said to him: Before we pray for mercy on your behalf, we must pray for mercy on our own behalf, as it is stated: “Then the moon shall be confounded, and the sun ashamed” (Isaiah 24:23). He said: Stars and constellations, pray for mercy on my behalf. They said to him: Before we pray for mercy on your behalf, we must pray for mercy on our own behalf, as it is stated: “And all the hosts of heaven shall molder away” (Isaiah 34:4).

Elazar ben Dordaya said: Clearly the matter depends on nothing other than myself. He placed his head between his knees and cried loudly until his soul left his body. A Divine Voice emerged and said: Rabbi Elazar ben Dordaya is destined for life in the World-to-Come. [The Gemara explains the difficulty presented by this story:] And here Elazar ben Dordaya was guilty of the sin of forbidden sexual intercourse, and yet he died once he repented. [The Gemara answers:] There too, since he was attached so strongly to the sin, to an extent that transcended the physical temptation he felt, it is similar to heresy, as it had become like a form of idol worship for him. When Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi heard this story of Elazar ben Dordaya, he wept and said: There is one who acquires his share in the World-to-Come only after many years, and there is one who acquires his share in the World-to-Come in one moment. And Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi further says: Not only are penitents accepted, but they are even called Rabbi.”[1]

III. Portrait of a Sinner

The beginning of the story establishes who REBD was as a person. The idea of him interacting with every prostitute in the world is not meant to be taken literally; this is what “was said about him.” His reputation in the wider world was that of a person utterly consumed with hedonistic obsession. This perception was shared by REBD himself; if not for the physical limitations of time, distance and exhaustion, his sincerest wish would be to live up to his reputation.[2] The story seems to indicate that REBD was a wealthy man, which allowed him to dedicate himself so single-mindedly to the pursuit of physical pleasure. However, as Maharal notes, money was not the only thing REBD was willing to dedicate to his obsession. His decision to embark on a dangerous and exhausting journey across seven rivers illustrates his willingness to expend all effort, and even risk his life, to fulfill his desire. This dedication reveals how inextricably bound up REBD’s identity was with the corrupt impulses he had set as the lodestar of his life.[3]

A point to note is that REBD is presented as a singularly immoral individual. However, from the perspective of Halakhah, his actions are not the most severe sins possible in the domain of sexual immorality. While visiting prostitutes is certainly prohibited, it is not in the same tier, in terms of punishment, as adultery and incest. As such, it is worth examining why REBD is seen as the apex of immorality.

This point can be addressed in two ways. As mentioned previously by Maharal and expanded by Rabbi Asher Anshel Katz, REBD’s identity had become intertwined with his attachment to this sin. The reason he is an extreme example of immorality is not because he committed extremely immoral sins, but rather because of the extreme obsession with which he dedicated his life to sin. Later on, this extreme nature was reversed and set to focus on the act of repentance.[4]

From another angle, perhaps it can be suggested that while his actions lacked the legal significance of more immoral acts, his attitude in the domain of sexuality was fundamentally corrupt. REBD practiced, and set as the central focus of his life, a crassly commercialized and materialistic version of one of the most sacred and creative acts in the human experience. He was not merely corrupted by immoral acts; he personified an approach to life that set corruption as its focus. This approach symbolized a conceptual inversion of intimacy that took this powerful force far from the domain to which it rightfully belonged.

IV. A Fateful Conversation

The next section, describing REBD’s interaction with the prostitute, is the turning point of the story. REBD’s focus and drive changes completely after this moment. Much of the commentary focuses on the meaning behind the prostitute’s comments and why it had such a profound effect on REBD.

One of the main questions to consider is why the prostitute felt compelled to comment on REBD’s spiritual state. After all, she was not a rabbi, ethicist, self-help guru, or therapist; what was the meaning behind her comment and what motivated her to make it?

Ben Ish Hai notes that a prostitute of this caliber would certainly take precautions, through the use of medications or fasting, to avoid an incident of this nature occurring while she was with a client. She viewed this unnatural occurrence as a heavenly sign, meant to symbolize the spiritual decay of REBD, and she shared this interpretation with him.[5]

Rabbi Yonasan Eybeschutz takes a different approach. The prostitute, noting some hesitance on the part of REBD, was trying to cajole him into continuing. To do so, she made an analogy: just like she could not change what had happened, and how her actions had affected the mood of the moment, so too REBD could not change his degraded spiritual status. Actions are permanent, and hoping to alter their effects is a pipe dream. It would serve no purpose for REBD to try to change the past through repentance; better for him to push all thoughts of spirituality from his mind and just enjoy what remained of his life in the physical world.[6]

There is a seeming irony, noted by Rabbi Aharon Leib Shteinman, in that REBD’s search for repentance is triggered by being told that repentance is impossible.[7] It was precisely this type of attitude that shocked REBD into action. This was a rock bottom moment; the challenge for REBD was to not give in to despair after hearing these words. Instead, he had to find the will and the means to return to God. Rabbi Shmuel de Uceda describes the false refuge of irredeemability; an individual will convince themselves that their sins are simply too great to be forgiven, and will give up all hope and effort for redemption.[8] On the surface, this attitude displays a seeming realization of the severity of sin. However, the hopelessness that it engenders reveals that it is not piety, but a toxic form of spiritual malaise. REBD rose to this challenge and refused to accept the fatalistic worldview of the prostitute.

Many of the great Ba’alei Mussar note that while REBD was a person deeply ensnared in his hedonistic habits, he still had an inner strength of mind and spirit that allowed him to step back from the edge of the abyss. The offhanded, dismissive comment from a prostitute, casually damning REBD to a life without a share in the world-to-come, was the catalyst he needed for repentance. It is precisely because he has some sense of spiritual value that her comment had such a profound effect on him. Faced with the prospect of a never-ending downward spiral of spiritual degradation, REBD marshalled all his forces of will and thought into achieving redemption. He inverted the single-minded focus he had once applied to the pursuit of physical pleasure. His new goal, which he seeks in the next section of the story, is self-knowledge, repentance, transcendence, and closeness to God.[9]

V. The World of Man, The World of Nature

REBD’s conversation with nature is the most cryptic part of the story. While we understand why REBD is seeking repentance, it is not clear why he seeks aid from nature, or what this help might be. There are several approaches in the commentaries:

- Metaphorical: REBD’s conversation with nature represents his attempt to analyze his own life, and to discover the root causes of his dissolute behavior. If he can prove that some factor beyond his control caused him to act the way he did, then he will be absolved of responsibility. This is the intent of the words “pray for mercy on my behalf;” i.e., serve as a justification to explain my behavior. Each element of nature represents a different influential factor in his life: the mountains represent his parents, the heavens and earth represent the society he grew up in, the constellations represent a fixed fate, the sun and moon represent wealth and riches. Each of these are examined by REBD as a possible cause of why he acted the way he did, but they are all ultimately rejected (as represented by the identical responses of the elements of nature, “before we pray for you, we must pray for ourselves”). REBD concludes that while these factors are all extremely influential, none of them were insurmountable. He did not have to be a single-minded hedonist, no matter what happened in his life to push him in that direction. This shows that perhaps for the first time in his life, REBD finally understands what motivates him, but that he has also finally taken responsibility for his actions.[10]

- Literal: More enigmatically, there are some approaches that seem to take this part of the story at face value. REBD was asking the world of nature to intercede on his behalf and help him achieve repentance. In this vein, Rabbi Moshe Pinto says that REBD was too ashamed to approach God directly, and therefore appealed to nature to act as an intermediary.[11]

- Theoretical: favored by Ritva and one opinion in Tosafot,[12] this understanding says that the exchange recorded in the Gemara is one that occurred in REBD’s head. It is an illustration of REBD’s thought process regarding repentance: “If I were to ask the sun and the moon, this is what they would tell me.”

- Conceptual: Maharsha makes the case that REBD was familiar with the idea that a person can become so spiritually deteriorated that he will need to die as part of repentance. However, he wished to be physically permanent like the mountains, that he should be able to repent without dying and departing the physical world. However, the verse that the mountains quote is meant to illustrate that physical permanence is an illusion; even the mountains erode and crumble. Nature is telling REBD that the physical world has cycles of existence and non-existence, and that he shouldn’t despair if the time has come for him to enter his preordained period of physical non-existence.[13]

- Mystical: The Grodzhike Rebbe takes a radically different approach. Human understanding ordinarily involves having information communicated through some medium. However, there is another level of insight, experienced by the Jewish people at Mount Sinai, where things do not need to be communicated because they are sensed innately. “We shall do and we shall hear;” the people had intuited the inner meaning of the Torah before it was ever communicated to them. A human being can reach a state of being so in tune with the world around them that they can innately sense the life force of everything, and see all existence as the desired manifestation of the will of God. When someone is in that state, he can “communicate” with anything. It seems, in the cryptic words of the Grodzhike, that this is the state REBD found himself in. After finally silencing the static of his own physical desires, REBD is tuned into a higher frequency. His communication with nature is meant to be taken extremely literally: REBD was suddenly locked in and understanding, innately sensing the world around him. Whereas up until now he had only had a sense of the world as far as it connected to his own inner drives and passions, suddenly he was looking outward and sensing the fullness of the world and its expression as the will of God. Seeing the world in this new light is what leads to his broken-hearted repentance at the end of the story.[14]

Whatever the precise nature of REBD’s “conversation with nature”, the conclusion he comes to is clear: “Ein ha-davar talui elah bi. (The matter clearly depends on me alone.)” This line represents more than just an acceptance of responsibility for prior behavior. REBD is also affirming his belief that he has the capacity to change, that the inner strength to return is within him. His conversation with nature has given him inspiration, insight, knowledge, but also the realization that ultimately the heavy lifting of the process of repentance is up to him.[15]

VI. Crying out From the Depths

Armed with inspiration and insight, REBD is ready to begin the repentance process. His mode of repentance has three components: the physical positioning of his body, the act of crying (to more closely translate the Gemara’s words: “he roared with weeping”), and his resulting death. The significance of each of these components is examined at length by the commentaries.

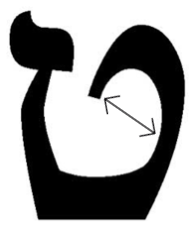

The positioning of his head between his knees has many different functions, both symbolic and otherwise. It is a fetal position, meant to illustrate REBD’s desire to return to a state of innocence like a child in a womb.[16] It represents that he allowed his body and its impulses to be in a state of dominance, ruling over his intellect.[17] This position is also used as a powerful means of supplicative prayer and prophetic meditation. It was practiced by Eliyahu Ha-Navi and Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa when praying. This meditative position was the method used by the four sages who entered the Pardes and achieved exalted levels of spiritual insight.[18] Another way to understand this position is as one of repentance through self-affliction, reflected in the shape of the letter Tet, according to the 14th century scribe Rabbi Shimon Ben Eliezer:

In his narrative explanation of the order of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, the tet has assumed this position, with the “head” of the right-hand part of the letter bent over to its “knees”, in an attempt to afflict itself and repent for negative thoughts caused by viewing the behavior of the letter adjacent to it; the het, which sinned by indulging in arrogance over its distinguished shape.[19] It is clear that REBD was utilizing this powerful position to convey in the most profound way possible his desire to repent and reconnect with God.

This desire also formed the basis of his weeping. Guilt, regret, shame, the pain of spiritual desolation: REBD’s tears were the expression of his life’s story, the encapsulation of his past experiences and his hopes for the future. The Alter of Novardok writes that REBD’s weeping was a firestorm of regret, a tearful elegy for his own misbegotten life. Through his contemplation of his actions, REBD was awakened to the holiness of God and the void his actions had created between himself and his Creator. This is what he was crying about and continued to cry about, even past the point where he had done teshuvah; he knew nothing beyond his own broken spirit.[20]

Rabbi Yaakov Ades provides a more metaphysical answer. He describes souls as having inner and outer layers. If the outer ones are affected by sin, they can be repaired through the inner ones, which remain in their pure state and influence and cleanse the others. REBD was at a point where he had corrupted every known layer of his soul. He turned to nature seeking external help; he believed he lacked the inner spiritual equipment to accomplish his goal. However, after the conversation with nature, he came to the conclusion that he could achieve repentance on his own. Through his intense crying, he discovered a secret innermost layer of himself, a layer capable of intense teshuvah, a part of his soul that he could not corrupt because he didn’t know it existed.[21]

The final part of REBD’s teshuvah was his immediate death following his crying in the valley. This is the crux of the story, as it seems to prove the Gemara’s original point that death is an essential part of repentance for the sin of immorality. The Gemara answers that REBD was different; he had become so attached to immorality that it became a form of idol worship. Both of these sins transform a person’s identity, strip him of his personhood and put him in a state of spiritual non-existence. While repentance is still possible, it is a process that requires the complete destruction of the hollow sense of physical existence created in the wake of the sin.[22]

Rabbi Avraham Yoffen writes that REBD, like Pharoah, experienced a certain curtailing of spiritual privileges. However, even though Pharaoh had his heart hardened by God, he still had opportunities for teshuvah, yet refused to take them. REBD had lost the right to ordinary teshuvah; the only option that remained was an approach that would destroy his body and end his life. However, unlike Pharoah, REBD had the strength of will and the desire for repentance to accept the option that remained in front of him.[23]

Rabbi Gershon Stern takes a different approach to the reason for REBD’s death. Since REBD was so attached to his desire for sin, it was very likely that he would return to his old habits, even if he was able to accomplish an astounding level of teshuvah at this moment. Therefore, God taking REBD’s life at the pinnacle of his spiritual accomplishment was actually a kindness, preventing the possibility of REBD losing what he had gained.[24]

A friend shared with me an approach to this part of the story that he saw written in the books of the Vorke Hasidim.[25] It involves the idea of “Midah tovah Merubah;” that the good and bad do not fully mirror each other, but rather the measure of good is always more expansive than the bad. When all the darkness that REBD created in his life was converted to light through his act of repentance, his physical body could simply not hold the enormous amount of light that was created, and it could no longer retain his soul.

This part of the story also receives considerable attention from commentators in the world of Halakhah. They examine the issue of REBD’s death, and whether it had the status of a suicide. Suicide is forbidden in Torah law, but it appears that REBD willfully ended his life for the cause of repentance and is praised for it. Hida resolves this issue by saying that REBD did not intend to kill himself, but rather that he died of “holy grief”, and therefore was praised by the heavenly voice. Although Hida seems to conclude that penitential suicide is forbidden, he cites dissenting opinions, including Shevut Yaakov and others, who see REBD’s story as proof for its permissibility.[26] In a letter, Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg (Rabbi Yehudah Ha-Hasid) (1150-1217) wrote approvingly of physically harsh forms of self-punishment; he endorses the request of a questioner who wished to drown himself as repentance for having been baptized and cites the story of REBD as support.[27] Among modern halakhic decisors, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, while not explicitly mentioning the story of REBD, forbids penitential suicide.[28] Rabbi Ovadia Yosef also forbids it, and explains that although REBD was praised by the heavenly voice for his good intentions, like other instances of suicide noted in Tanach, Gemara, and Midrash, he acted under a misapprehension about the permissibiltiy of penitential suicide.[29]

VII. The Eternal Eulogy of REBD

The epilogue of the story centers around the announcement of the heavenly voice and Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Nasi’s reaction to the story of REBD. Being assured entry to the world to come is a rarefied status, shared by REBD, Rabbi Akiva, and several others, many of whom are also mentioned in the first chapter of Masekhet Avodah Zarah. The precise spiritual implication of this stature, and its position in the sequence of the messianic era, is spelled out by Ramban.[30]

A question posed by many commentators is how REBD achieved this spiritual status, and the title “Rebbi,” as he did not lead a pious life and never taught Torah to any students. One fascinating answer is that REBD was the reincarnation of Rabbi Yohanan Kohen Gadol. Rabbi Yohanan’s life was the inverse of REBD’s; while REBD repented at the end of a corrupt life, Rabbi Yohanan slipped into heresy after eighty years of virtuous behavior.[31] REBD’s one moment of repentance fulfilled that which was lacking from Rabbi Yohanan, completed his soul’s work, thus earning the title “Rebbi.”[32]

Rabbi Yehudah cries as well, and makes two observations: that an entire world can be acquired in one instant, and that the stature of those who repent is so lofty that they earn the title “Rebbi”. This coda emphasizes the value of one single moment, and the exponentially greater potential for a life composed of so many moments. What REBD did in the final moment of his life illustrates what any person can do, with any instant of their life. This infinite potential is what moved Rebbi to tears.[33]

According to the Kotzker, Rabbi Yehuda was crying over the bittersweet end of REBD’s life. He saw what REBD could have been, had his whole life been lived in the mode that he achieved in his final moments.[34]

In regards to Elazar ben Dordaya earning the title of “Rebbi”, Maharal makes the point that the name Elazar is composed of the words “El” and ”azar,” meaning God helps and that “Dordaya” means the spoiled dregs of wine. Despite their decayed state, something useful and substantial can still be made out of these dregs. For Elazar, this was accomplished by tapping into divine inspiration and transforming himself from an exemplar of moral corruption into the personification of ultimate repentance. It is only because his teshuvah was so profound, such a complete 180, that his story makes such a strong impression, and proves how powerful repentance is. In this sense the identity of “Rabbi Elazar” was the “son” i.e. the product of, “Dordaya;” he was only able to be the “Rebbi” who teaches the world about teshuvah because he was “Dordaya” the degraded wine. Without his moral decay, he never could’ve been what he became: the champion of teshuvah, the ultimate exemplar of redemption.[35]

VIII. It’s Never Too Late

Shelah presents a novel reading of the Talmudic dictum: “Listen to whatever the master of the house tells you, except when he tells you to leave.”[36] He explains that “doing whatever the Master of the House tells you” refers to fulfilling the commandments. “Being told to leave” refers to signs in the physical world that seem to point to a person’s irredeemability. In the story of Elisha ben Abuyah, the sage turned apostate, this was the heavenly voice that proclaimed that he could not repent.[37] For REBD, it was the fatalistic words of the prostitute. However, these signs are not to be taken at face value; when we are told to leave, we refuse to listen. No matter what it takes, we will do what is needed to stay with the Master. Using Elisha ben Abuyah and REBD as case studies, Shelah illustrates that teshuvah is always possible, and the main challenge is not giving in to despair.[38]

This is the fundamental lesson that REBD gifted to the world. His story illustrates many things: The value we should place on every single moment, the need to control our habits, the importance of taking responsibility. But underneath it all is the idea that the human being and God are irrevocably connected, and that no matter how far we go, we can always return. The only threat is the idea that we would believe the worst possible narratives about ourselves. If REBD, with an entire lifetime of wrong decisions, and with every reason to let himself drown in a morass of shame, chose instead to fight his way back with dogged determination, each and every one of us can do the same. May it be the will of God that we always remember the lessons of Rabbi Elazar Ben Dordaya, and that in our darkest moments we recall that our Father is just a teardrop away.

[1] Avodah Zarah 17a, translation adapted from the William Davidson edition of the Koren Noe Talmud.

[2] Rabbi Pinchas Goldwasser, Tapuhei Zahav (B’nei Brak: 2012), 867.

[3] Hiddushei Aggadot, Volume 4.

[4] Rabbi Asher Anshel Katz, Shemen Rosh, Volume 9 (Brooklyn: 2009), 233-234

[5] Ben Yehoyada, Avodah Zarah 17a

[6] Rabbi Yonasan Eybeschutz, Ya’arot Devash, Volume 1 (Jerusalem: 2012), 39.

[7] Rabbi Aharon Leib Shteinman, Yimaleh Pi Tehilatekha, Volume 1 (Bnei Brak: 2003), 143.

[8] Rabbi Samuel ben Isaac de Uçeda, Medrash Shmuel (Venice: 1585), 42.

[9] Rabbi Shlomo Harkavy, Ma’amarei Shlomo, Volume 1 (Jerusalem: 2001), 215; Rabbi Simcha Zissel Ziv Broida, Hokhmah U-mussar, Volume 2 (Brooklyn: 1957), 412; Rabbi Yeruham Levovitz, Da’at Hokhmah U-Mussar, Volume 2 (Brooklyn: 1969), 43.

[10] Rabbi Aharon Lewin, Ha-derash Ve-HaIyun, Bereishit (Biłgoraj: 1928), 119-122.

[11]Rabbi Moshe Pinto, Imrei Moshe, Volume 2 (Petah Tikva: 2005), 119-122; for additional reading on the topic of praying to intermediaries, see Torah Temimah Exodus 22:19 and Avodat Ha-elekh on Mishneh Torah Hilkhot Avodat Kokhavim 2:1.

[12] Avodah Zarah 17a: Ritva s.v. “Amru Ad She-anu Mevakshim Rahamim” (p. 467 in the Mossad Ha-Rav Kook edition); Tosafot s.v. “Ad She-anu Mivakshim Alekha Rahamim.”

[13] Hiddushei Aggadot, Avodah Zarah 17a.

[14] Rabbi Yisroel Shapira, Binat Yisroel (Warsaw: 1938), 158-159.

[15] Rabbi Elazar Menahem Man Shach, Mahshevet Mussar, Volume 3 (Bnei Brak: 2006), 330-331.

[16] Ben Yehoyoda, Avodah Zarah 17a

[17] Rabbi Eliezer Zussman Sofer, Yalkut Eliezer, Volume 3 (Paks: 1911), 500.

[18] Rabbi Aharon Berakhiah, Ma’avar Yabok (Mantua: 1626), 93-94.

[19] Rabbi Simeon Bar Eliezer, Barukh She’amar (Warsaw: 1877), 66-67.

[20] Rabbi Yosef Horowitz, Madregat Ha-Adam (Brooklyn: 1947), 370-372.

[21] Rabbi Yaakov Ades, Divrei Yaakov Al Aggadot Ha-Shas (Jerusalem: 2011), 474-477.

[22]Rabbi Yehudah Loew, Netivot Olam: Netiv Ha-Teshuvah (Jerusalem: 1997), 131-132; Rabbi Hayyim Volozhiner, Derashot (Kiryat Sefer: 2017), 14.

[23]Rabbi Avraham Yoffen, Ha-Mussar Ve-HaDa’at Shemot/Vayikra (Jerusalem: 1978), 35-38.

[24] Rabbi Gershon Stern, Yalkut Gershoni Al Aggadot Ha-Shas, Volume 3 (Sighet: 1922-1927), 33.

[25] I have not seen the original inside, as I was unable to locate it.

[26] Rabbi Hayyim Yosef Dovid Azulai, Marit Ha-Ayin Al Masekhet Avodah Zarah (Jerusalem: 1960), 93.

[27] Cited by Emese Kozma, “Schedules of Penance for Repentant Apostates in Austria and Germany in the 15th Century: Publication of a Responsum from Ms. Oxford 784 Fols. 25b–26a,” Alei Sefer: Studies in Bibliography and in the History of the Printed and the Digital Hebrew Book 24-25 (2015): 189-213.

[28] Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, Igrot Moshe Hoshen Mishpat, Volume 2 (New York: 1985), 300.

[29] Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Yalkut Yosef: Hilkhot Bikur Holim V-Avelut (Jerusalem: 2004), 773-774.

[30] Rabbi Moshe ben Nahman, Sha’ar Ha-Gemul (Bnei Brak: 1969), 102.

[32] Rabbi Hayyim Vital, Likutei Torah (Vilna: 1879), 254.

[33] Rabbi Tzvi Palei, Nahalat Tzvi (Jerusalem: 2004), 318- 326.

[34] Cited by Rabbi Pinhas Menahem Alter in Ari She-BiHaburah (Jerusalem: 2009), 91-92.

[35] Rabbi Yehudah Loew, Hiddushei Aggadot, Volume 4 (Jerusalem: 1972) 40.

[38] Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz, Shnei Luhot Ha-Brit: Aseret Ha-Dibrot (Jerusalem: 1996), 442-444.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.