Update: Jonathan Muskat’s response to Jonathan D. Sarna’s essay can be found here.

Jonathan D. Sarna

In the wake of recent actions by the President of the United States, Rabbi Jonathan Muskat proposes to revise the traditional prayer for the government, Ha-noten Teshu’ah, originally composed five hundred years ago. His new text invokes Divine blessings upon the country and its citizens, rather than upon its leaders, and banishes the lofty language (“bless, protect, help, and exalt”) that the standard prayer applies to the President, Vice-President, and other officers of the country.

Rabbi Muskat’s proposal calls to mind the original prophecy of Jeremiah (29:7) that underlies all diaspora prayers for the country: “seek the peace of the city into which I have caused you to be carried away captives, and pray to the Lord for it, for in its peace shall you have peace.” Jeremiah speaks only of praying for the “city,” the place where Jews lived; he says nothing about praying for the city’s leaders. To this day, for that reason, some prefer the term “prayer for our country” rather than “prayer for our government.”

Leaders, however, are in most cases, inseparable from the places they lead. Ezra (6:10) in Persia thus prays for “the life of the king and of his sons,” and Pirkei Avot, in a famous passage (3:2), enjoins Jews to “pray for the welfare of the ruling power, since but for the fear of it, men would swallow each other alive.” As we know from events of our own time in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere, the fate of a place heavily depends upon the wisdom and actions of its leaders.

Significantly, the political context for the statement in Pirkei Avot is Rome, whose leaders many of the rabbis loathed. Nevertheless, Jewish political philosophy from the early rabbis onward consistently held that a government, even an oppressive government, is superior to anarchy. From ancient Babylonia to the contemporary Soviet Union Jews have thus prayed fervently for governments that they actually despised.

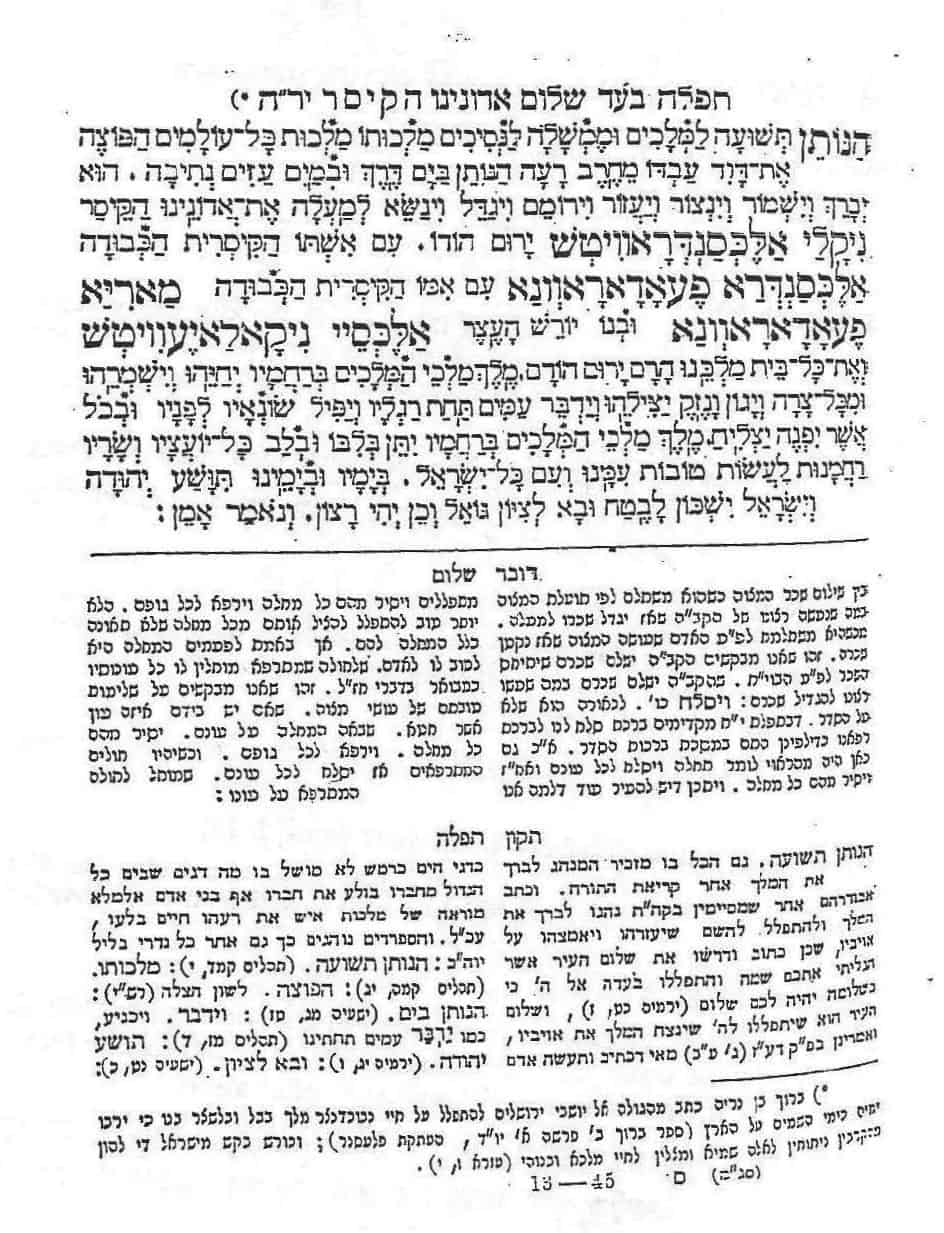

Rather than altering traditional prayers, as Rabbi Muskat proposes, rabbis of old cleverly disguised their views of hated governments, displaying virtuosity in what the philosopher Leo Strauss called “persecution and the art of writing.” So, for example, a Russian siddur from the late Tsarist era contains the traditional Ha-noten Teshu’ah prayer for Nicholas, Alexandra, queen mother Maria and crown prince Alexei whom the prayer exalts in the loftiest of tones. A microscopic footnote, however, explains that, according to the apocryphal book of Baruch (1:11), Jews are enjoined to pray even for the life of King Nebuchadnezzar. Through this tacit aside—so oblique that it eluded the watchful censor’s pen—the siddur covertly linked the Tsar to the most despised of diaspora monarchs, even as it overtly celebrated his name in large black letters.

Indeed, Ha-noten Teshu’ah itself is in many ways a subversive prayer. Its manifest language exudes Jewish loyalty and faithful allegiance. At the same time, its esoteric meaning, presumably recognized only by an elite corps of well-educated worshippers, hints at spiritual resistance, a cultural strategy well-known among those determined to maintain their self-respect in the face of religious persecution. So, for example, the prayer begins with a verse modified from Psalm 144:10: “You who give victory to kings, who rescue[s] His servant David from the deadly sword.” The next line of that Psalm, not included in the prayer but well-known to Jews who recite it every Saturday night, and deeply revealing in terms of the prayer’s hidden meaning reads, “Rescue me, save me from the hands of foreigners, whose mouths speak lies, and whose oaths are false.”

Rabbi Barry Schwartz has pointed to several more esoteric readings in the prayer, including Isaiah 43:16, which forms part of a chapter predicting the fall of Babylon; Jeremiah 23:6, cited in the prayer’s conclusion, that preaches the ingathering of the exiles and the restoration of the Davidic dynasty; and Isaiah 59:20 (“He shall come as redeemer to Zion”) which is preceded two verses earlier by a call for vengeance, a sentiment not found in Ha-noten Teshu’ah but likely on the minds of some Jews who recited it. Simultaneously, then, centuries of Jews have prayed aloud for the welfare of the sovereign upon whom their security depends, and read between the lines a more subversive message, a call for rescue, redemption, and revenge. A famous line in the musical Fiddler on the Roof echoes this tradition (“A blessing for the Tsar? Of course! May God bless and keep the Tsar … far away from us!”), and Rabbi Muskat, perhaps unconsciously, now brings a similar message into his synagogue.

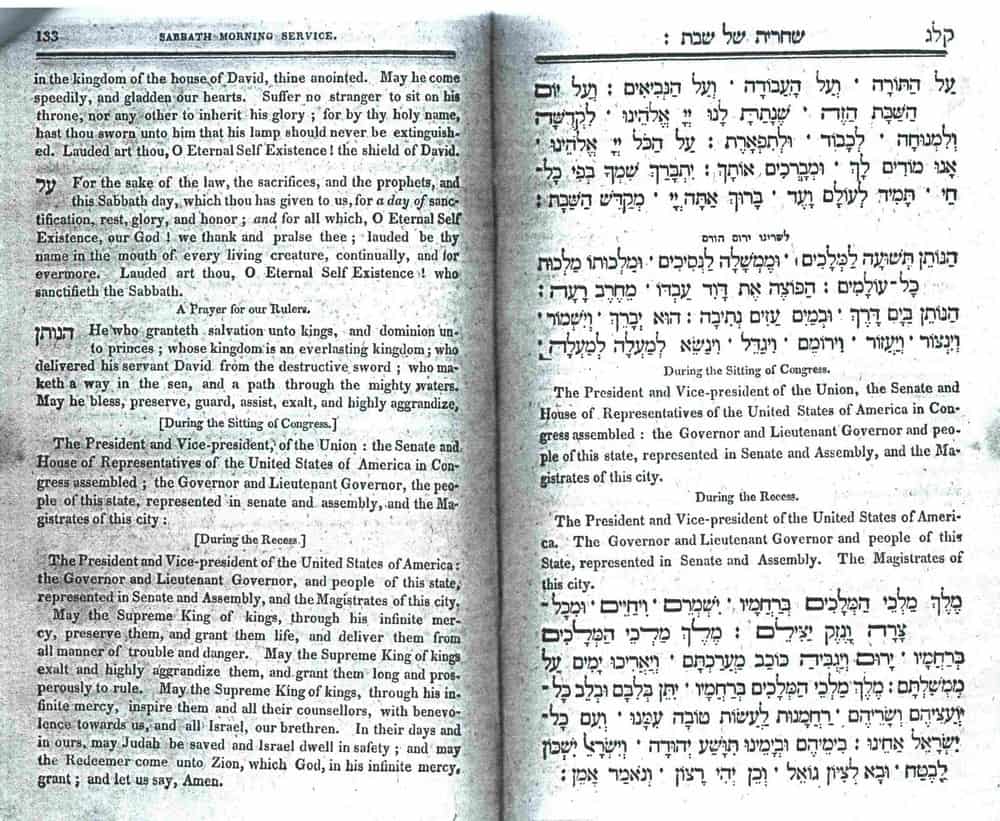

A close comparison between the Ha-noten Teshu’ah text in the Russian siddur mentioned above and in contemporary American siddurim confirms Rabbi Muskat’s claim that Ha-noten Teshu’ah exists in numerous versions and is somewhat more malleable than tefilot of greater antiquity. Most significantly, following the American Revolution, the prayer was radically depersonalized in the United States, based on the idea that the New Nation honors “the office” not “the man.” From then onward most American synagogues have prayed for the nation’s officeholders without naming them (“the President”), a totally different practice than in other countries (including Great Britain) where kings and queens are commonly referenced by name. In the very first post-Revolutionary American siddur, printed in 1826, a distinction was even drawn between how Ha-noten Teshu’ah should be recited “During the Sitting of Congress” and “During the Recess,” as if to underscore that members of Congress are only special (and worthy of being included in the prayer) when Congress is actually in session; otherwise its members are fellow citizens along with everybody else. That practice, and the post-Revolutionary custom of sitting rather than standing for the prayer, both subsequently disappeared.

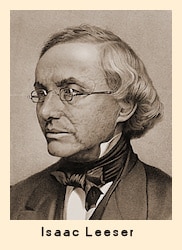

Other changes introduced into the Ha-noten Teshu’ah prayer in the United States enjoyed greater staying power. In his publication of the Ashkenazi siddur (1848), Isaac Leeser quietly dropped from the prayer the line “may he [the sovereign] subdue nations under his feet, and make his enemies fall before him, and in whatsoever he undertaketh may he prosper.” Most American versions followed Leeser’s lead and likewise dropped that militaristic line. Similarly, the original prayer pleaded with God to instill mercy (rahmanut) into the heart of the sovereign, his advisors, and his officials. In America, where rights rather than rahmanut are supposed to govern the relationship between leaders and led, the reference to rahmanut was for the most part abandoned—although Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz, in his British siddur, pleaded for the word’s return.

Throughout the years there have been many calls to expunge Ha-noten Teshu’ah from the liturgy altogether, not just because Orthodox Jews opposed the policies of a particular President, as Rabbi Muskat does, but also because a prayer that opens with a reference to “kings” hardly seems appropriate for a modern democracy. Many nineteenth-century Orthodox prayer books published in America printed a quite different prayer, beginning with the words Ribon Kol Ha-Olamim. That prayer, composed by Rabbi Max Lilienthal when he briefly served as chief rabbi of New York, focused locally, depicted America as a mini-Zion, and was in many other ways too eccentric to survive. A more recent prayer composed by Rabbi David de Sola Pool for his 1960 Modern Orthodox siddur also failed to capture widespread favor. Professor Levi Ginzberg’s 1927 prayer, included in all Conservative and Reconstructionist prayer books, is by far the most successful of twentieth century prayers for the government, and remains timely (“May citizens of all races and creeds forge a common bond in true harmony to banish all hatred and bigotry”). But it is unlikely to win acceptance in Orthodox circles.

Whether Rabbi Muskat’s amended version of Ha-Noten Teshu’ah does win widespread favor remains to be seen. In the meanwhile, it is worth recalling the words of the great American religious historian Martin Marty in connection with these kinds of prayers. “Governments,” he wisely observed, “ultimately receive the prayers that they deserve.”

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.