Victor M. Erlich

In modern English, a leviathan is any huge being, man or beast, especially a whale. But the idea of a leviathan has a much richer set of meanings in literary English. Indeed, Melville refers to Ahab’s fatal whale, Moby Dick, as a leviathan, matching the Hebrew-named captain with a beast named in the Hebrew Bible. Thus says Ishmael, Moby Dick’s, narrator: “When I stand among these mighty Leviathan skeletons, skulls, tusks, jaws, ribs, and vertebrae, all characterized by partial resemblances to the existing breeds of sea-monsters, . . . I am horror-struck at this anti-Mosaic, unsourced existence of the whale, which, having been before all time, must needs exist after all humane ages are over” (104). “Horror-struck,” Ishmael, named after the first-born son of Abraham, acknowledges that the Leviathan has infiltrated and overwhelmed his mind, as was the case for the original Ishmael, who was cast out. His dull physicality prevented him from grasping his father’s covenant, even though Ishmael means “Man of God.”

The “anti-Mosaic” beast to which Ishmael refers appears in the very on the first page of the Five Books of Moses, where it is found among those animals brought forth on the fifth day of creation. This beast is called the teninim, in the plural, for in ancient Hebrew the plural is often used to signify immense significance, as in the very name of the Creator, Elokim. The renowned eleventh-century commentator, Rashi, identified these “large fish” as the leviathan, and this is the term that the knowledgeable King James translators passed on to us, in their well-wrought English.

However, it is not clear what animal the ancient Hebrews had in mind. Perhaps leviathan referred to the Egyptian crocodile, perhaps to a rock snake or another terrifying serpent. More importantly, the leviathan’s metaphorical meanings for literate Hebrews far outweighed the heft of the imagined beast. King David’s Psalm 104 draws on resonances deeper than the whale’s wake. “O Lord, how manifold are thy works! In wisdom hast thou made them all: the earth is full of thy riches. So is the great and wide sea, wherein are things creeping innumerable, both small and great beasts” (104:24-25). David goes on to liken the endeavors of man to the play of those great beasts in the sea: “There go the ships: there is that leviathan, whom thou hast made to play therein” (104:26). David juxtaposes the builders of ships with the great beast, but what possible connection could they have? What is there about the leviathan that can be compared to shipwrights?

The author of the Book of Job expands on the connection between the leviathan and man. To this poet, the leviathan does not represent a serpent far away in the deeps; rather, it is related to Job’s own impoverished understanding. The Lord admonishes Job for failing to understand the difference between God and the beast. Can Job not distinguish the covenantal God of Abraham from his own bestial thinking? “Canst thou draw out leviathan with a hook or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down? Canst thou put a hook into his nose? Or bore his jaw through with a thorn? Will he make many supplications unto thee? Will he speak soft words unto thee? Will he make a covenant with thee?” (40:25-28) God seems to have created the beast to remind the “stiff-necked” Hebrews that they cannot reliably forsake their idolatry, their recidivist habit of falling back on the belief in golden calves of all kinds. Does Job know anything about the leviathan in his own mind? Does he know anything about his repeated inability to distinguish between the Lord who pleads for his people’s devotion and the leviathan who can take no interest in him? Even the righteous Job seems to have no ideas about what to make of the beast, even though the beast is himself, sporting a “nose,” just like a man.

The prophet warns the children of Israel that their failure to keep the covenant with their God will lead to their destruction. Speaking about the failure of men, the punishment of the Hebrews to the punishment of the leviathan, which serves as an emblem of the wayward Hebrews themselves: “In that day the Lord with his hard and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan, the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea (Isaiah 27:1). That sea is the morass of the Hebrew mind, which leads to the Hebrew’s inability to recognize that they are chosen only in the sense that they are obligated to choose righteously. The dragon that needs slaying is the Hebrew propensity for idolatry.

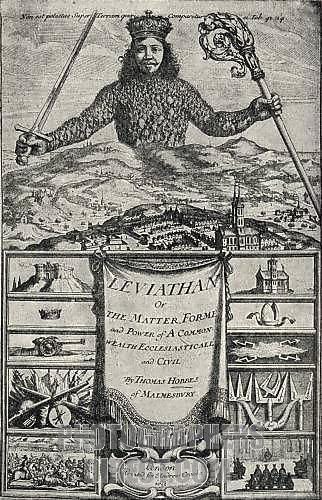

The great philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, writing during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century, titled his book on man and society Leviathan, precisely to emphasize the leviathan as a representation not of sea serpents but of man himself, as well as his church, and his larger society. Hobbes’ full title goes like this: Leviathan Or The Matter, Forme, and Power of A Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil.

Because human nature is Hobbes’ subject, he begins with a long exploration of the nature of man, his psychology, his passions and his intelligence, finding that the vast complication of the human mind is indeed a leviathan, as are the conglomeration of his religious beliefs and the troubled societies he founds. The leviathan is within us all. This is perhaps best illustrated by the book’s frontispiece, which was designed by a Dutch artist under Hobbes’ supervision. Boldly presented is the figure of a man, a representation of Mankind as a whole, and, more specifically, a royal figure, supposedly the only one who can, crowned with proper training, harmonize the psychological, spiritual, and social aspects of the human leviathan. This makes Hobbes, incidentally, the founder of the modern, psychological understanding of the human brain as a huge, complex entity, with distinct capacities for multitudinous arts, from armaments to manuscripts to ziggurats:

The need for this hypothetical royal figure to master the human leviathan is best summarized in Hobbes’ own, most famous words. The leviathan of mankind, according to Hobbes, is a beast that leads to “war of all against all.” “In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently, no culture of the earth, no navigation, nor use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” This one sentence is an apt summary of the challenge that faces any Church or King wishing to govern the human mind. Whether or not Hobbes knew how to produce the best Church or King is, perhaps, less important than an agreement on what the search entails.

Do we know how to rule the leviathan in our minds, our churches, and our cities? For Hobbes, the possibility of mankind developing the necessary knowledge rests on the skills given to man by the Creator, who created man in His own image, on the sixth day of creation, the leviathan already present. Man is both created and creative, endowed by his Creator to be so. Man’s art imitates God’s art, according to Western religion. Thus Hobbes gives us this in his Introduction: “Nature (the Art whereby God hath made and governs the World) is by the Art of man and in many other things . . . . For by Art is created that great Leviathan called a Common-wealth, or State {which} is but an Artificial Man, . . . for whose protection and defense it was intended; and in which, the Sovereignty is an Artificial Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body.”

Writing at the same time as Hobbes, John Milton takes up the challenge to apply artfulness to master the monsters of the mind. In Paradise Lost, he likens the Leviathan to Satan, who early in the masterful epic is floating in the ocean that is hell. Satan, no longer an angel in God’s heavenly Court, is now a “Sea-beast” with the power to pull any man, or even Mankind in general, into the unforgiving deep.

Thus Satan…

With Head up-lift above the wave, and Eyes

That sparkling blaz’d…

Lay floating many a rood, in bulk as huge

As… that Sea-beast

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th’ Ocean stream.

(Paradise Lost I, 192-201)

Satan may be as “huge” as the Hebrew’s mythical and metaphorical “Sea-beast,” but it is his evil inclination, rather than his impressive bulk, on which Milton rivets our attention. Satan the Leviathan is emphatically manlike. Just like recalcitrant, sinful men, he has a “mind”; he surveys his new territory like any mindful landowner:

Is this the Region, this the soil, the Clime,

Said then the Lost Arch-Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav’n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light?… Hail horrors, hail

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang’d by Place or Time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

(Paradise Lost I, 242-255)

Milton sees the Leviathan as an important part of the Creation because this “hugest of living creatures” heralds the creation of Man on the sixth day. Though Leviathan be the hugest of living creatures, he is but a mimicry of the grandest of God’s creation, the one gifted with God’s own creativity, with a mind that “is its own place.” Man, with the human capacity for creativity and poetry, is alone capable of understanding the Leviathan as an idea, and only Man is given dominion of the beasts of “Sea and Air.” But to exercise this dominion, Man must master the Leviathan of his own mind.

Thus both Hobbes and Milton elaborate in detail what the Hebrews call the Yetzer ha-Ra, the evil inclination of the human mind as it is created. This malevolent capacity of the mind is able to overwhelm the Yetzer ha-Tov, that creative part of the mind that is divinely favored. The mind contains the capacity both to mar God’s creation and to draw on the poetry of King David and master the bestial drives of Leviathan.

Milton is emphatic in his support of Christian doctrine, telling us that we will remain lost to the paradise of heaven without the divine intervention of Jesus, but the poet inadvertently hints at the old Hebrew belief that the divinely created mind “Can make Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n,” leaving open the possibility that a God-fearing man might just be able to create a life worth living without the help of “one greater Man.” Thus in the very opening of Paradise Lost we find an allusion to both Jesus and Moses:

Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste

Brought Death into the World, and all our woes,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat,

Sing Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or Sinai didst inspire

That Shepherd [Moses], who first taught the chosen Seed,

In the Beginning how the Heav’ns and Earth

Rose out of Chaos.

(Paradise Lost I, 1-10)

Nodding to Christian and Hebrew traditions, as well as Greek, with appropriately italicized diction, Milton places the proper use of man’s creativity in spiritual and intellectual capabilities. He uses the capitalized word Man twice, one for the progeny of Adam, the other for that greater Man. In any case, the Leviathan that is Satan is one with the leviathan in the human mind, as seen by Hobbes and Milton, as well as by Isaiah and Job in the Hebrew Bible. That the readers of Paradise Lost represent those among mankind who must attend to the leviathan in their own minds is the subject of Stanley Fish’s Surprised By Sin, a marvelous, deeply penetrating reading by my former professor, with whom I studied some fifty years ago.

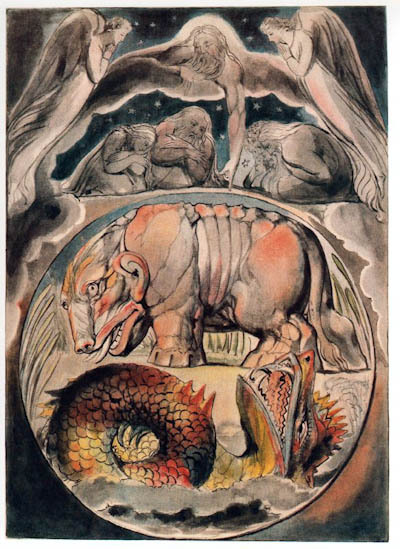

The author of the Book of Job has God add to His use of the leviathan a portrait of the behemoth (another Hebrew word brought into English by the King-James translators). The two beasts are coupled in adjacent verses, both linked to God’s creativity, but also brought into being along side of man, as if the beasts are one with the bestial part of man. Thus God focuses Job’s attention: “Behold now behemoth, which I made with thee; he eateth grass as an ox. Lo now his strength is in his loins, and his force is in the navel of his belly. He moves his tail like a cedar; the sinews of his stones are wrapped together” (40.15-17). This description of this powerful beast with an animal’s appetite segues immediately into God’s questioning Job about mortal man’s control over the leviathan: “Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook?”

The English poet, William Blake, captivated by the poetry of the Book of Job, submitted the whole of it to his own artistic vision. One of his illustrations for the version of Job that he himself published features God creating Leviathan and Behemoth (this word, too, is in the plural, not because it is many but because its meanings are manifolds:

Flanked by two cherubs, God creates the behemoth and leviathan over the shoulders of huddling prototypes of mankind. These diminished figures shelter themselves under the canopy of God as they rest on a bubble of bestiality, the latter larger than the former.

There is a fearful symmetry here between divine and human creativity, and between mankind’s cherubic propensities and his animal drives. Blake the poet and artist is the creator of this vision of created man.

Mankind is created in God’s image to be creative, but that creativity thrusts itself into the world with a duality, to which Blake returns in his most famous poem, “The Tyger.”

Tyger tyger! burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry.

In what distant deeps or skies

Burst the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

An what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer: what the chain?

In what durance was thy brain?

What the anvil’ what dread grasp

Dare its deadly terror clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears,

And water’d heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger! Tyger burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Of this poem, the most frequently anthologized of all English poems, much has been said, but let me add that Blake here meditates on God’s simultaneous creation of both beauty and evil in a way that fuses God’s creation with mankind’s sometimes-bestial inventiveness. Blake mixes his diction so that he alludes to the divine (the “immortal“ “who made the Lamb,” that is Christ), the human (“anvil,” “hammer,” “chain,” “spear”, “shoulder,” “hand,” “smile,” “grasp,” “clasp”), and the ferocious (“deadly terror”).

Some of Blake’s phraseology is not clearly pertinent to God, mankind, or beasts. To whom or to what does “What dread hand & what dread feet” refer? To the tyger that thrusts forth paws rather than hands and feet? To God, who needs neither hands nor feet? To the human beings whose hands work with anvils, throw spears, and put others in chains? Why would exercise his creativity in “durance,” which is a prison? Is Blake inquiring about divine “art” or human “art,” godly “wings” or Icarus-like “wings”? The word “dare” seems appropriately applied to creative men, but Blake uses this verb twice to describe God during His creation of the tyger, even though the depiction of God as a daredevil is sacrilegious. Does the word “sinews” refer only to the tendons of the tyger, or is Blake also alluding to the “sinews” of the behemoth, as described in the King James translation of Job? Does not God say to Job, “I made [the behemoth] with thee”?

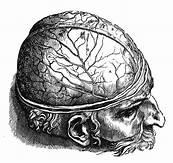

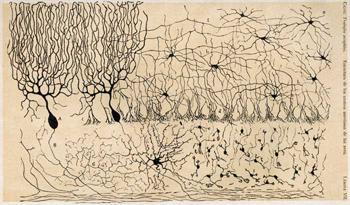

Is the fearful symmetry between benevolent creativity and satanic conniving in the tyger’s brain, or in God’s brain (assuming for the moment that God’s creativity arises from a brain), or is it in the human mind? In whose “eye,” not in any eye, but specifically in “thine eye,” is the fire burning? Thine is a word often applied to the divinity, sometimes to a beloved, virtually never to a tiger. And tigers are not usually found “burning bright in the forest of the night. ”But brutishness does burn bright in the forest of the human brain. Anatomists from Vesalius in Renaissance Italy to Ramon y Cajal in 19th-century Spain illustrated the forests of the human brain. Here is Vesallius’ drawing of the brain’s tree-like circulation, which Blake, a fair anatomist, would likely have seen:

And here is Ramon y Cajal’s meticulous drawing of what he saw through his microscope of the forest in the night of the brain’s cortex:

When Blake, Job’s illustrator, asks about the tyger’s origin, “in what deeps,” is he not alluding to the leviathan in its watery depths? And are not those depths in the human mind, too, as the Bible, John Milton, and Thomas Hobbes teach us? Do we not all live with the tyger, the behemoth, and the leviathan in our cranial globe? Galen, the Greco-Roman founder of medical anatomy in the second century, C.E., dissected the brains of Barbary monkeys, finding in the their “little bellies” (for this is the meaning of ventricles) sloshing cerebral-spinal fluid, literally the remnant of internalized, archaic seawater, evolved over the ages with ample room for beasts of appetite. These ventricles, in the brain’s very center, says Galen, provide the abode of the soul:

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.