Yaakov Jaffe

Note: This is Part I of a two-part series presenting the ideological preference of choosing non-ideological texts. This article responds to the recent article by Yosef Lindell, and its forthcoming companion will analyze the Soloveitchik Siddur.

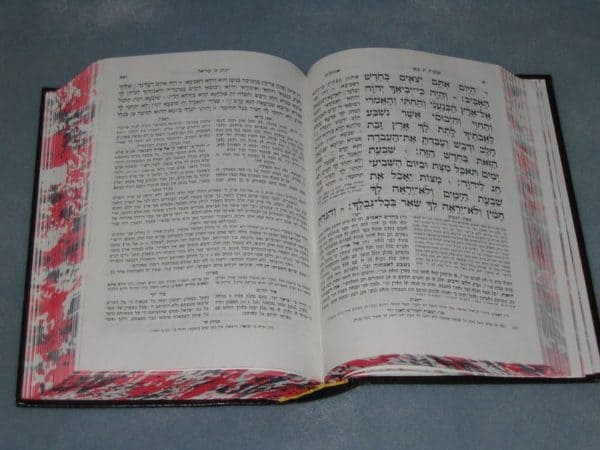

It has become commonplace in Modern Orthodox circles to lament the lack of alignment between the beliefs of the movement and some of the editions, translations, and versions of ritual texts that members of the movement use. These critiques are often welcome, such as Deborah Klapper’s recent excellent essay about the Haggadah for Pesach, and tend to frame ArtScroll Publishers as the almost villain who has taken the ideologically open, natural, innocent, uncorrupted foundational texts of Judaism and colored them with an Ultra-Orthodox translation, skew, or commentary. Yosef Lindell recently addressed the question as well in regards to the ArtScroll Chumash which, despite regularly citing Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the leader of twentieth-century Modern Orthodoxy, also fails the test of fealty to Modern Orthodoxy in his view.

Let us grant for a moment that many Modern Orthodox Jews use texts that do not perfectly match their ideology or philosophy. What response we should take to this observation? First, we must ask whether we can or should use a text that is not perfectly aligned just because it is superior in some other way, or whether the demands of ideological purity necessitate that we use an inferior text if it aligns with our beliefs. Second, if we must change texts, what is preferable: a ritual text that is perfectly neutral in ideology and could be used by all Jews or one that is instead positively reflective and supportive of our ideology? Third and finally, how do the necessarily narrow and nuanced lines used to define the sub-groups and viewpoints within Modern Orthodoxy relate to the next generation of ostensibly aligned Modern Orthodox texts? Should two different Modern Orthodox Jews living in the same town, who both recite the prayer for the State of Israel, necessarily use two different Siddurim if each recites a slightly different version of the Prayer for Israel? In that case, no text could ever survive the scrutiny of having to perfectly match each Jew’s unique viewpoint in all the aspects of Judaism the texts address.

Lindell’s piece argues that his preference is to find a Humash that matches his ideology. He answers to the first question that we should not use a text if it does not align perfectly, to the second question that an aligned Chumash is superior to a more neutral one, and to the third that the hitherto unproduced Humash will match his ideology sufficiently. But part of me wonders whether my own approach to Tanakh conforms with his and whether his Humash would resonate with me, which furthers the problem that if we all must find a Humash that matches perfectly, then we must all use our own unique Humash.

Pondering the Raison D’être of a Ritual Text: To Exist on its Own Terms or to Broadcast an Ideology

For me, there is a more grave concern when Modern Orthodox Jews flock to a different ritual text because it aligns more purely with their own ideology, and that is that the ritual text ceases to be important for its own sake (as a Siddur, Humash, or Hagaddah), a vehicle for transmitting sacred texts and values through the generations, but instead becomes a mere bit player in a larger drama about movements and self-identification. (“I use this Siddur because in many ways it demonstrates that I am a proud Modern Orthodox Jew.”) This carries the risk that readers will stop reading the text of the Humash or being taken by the poetry of the Siddur and instead become hyper-focused on ideological markers that appear in those ritual texts. And for reasons that we will demonstrate below, the subordination of prayer within the mind of the person at prayer, beneath the selection of outward identifiers of ideology undermines the very purpose and notion of prayer itself.

In 1978, Rabbi Soloveitchik authored a short essay entitled “Majesty and Humility” in Tradition, in which he poses a dichotomy critical for Jewish religious experience and prayer. He describes one pole as majestic humanity, striving for victory and sovereignty, as “Man sets himself up as king and tries to triumph over opposition and hostility.” The other pole is humble humanity, full of “withdrawal and retreat,” which appreciates the smallness of human beings in the scope of the cosmic order. In the essay, prayer is an example of man in the mood of humility, of withdrawal, who finds the Almighty not when humanity triumphs over the forces of nature, or in the scope of the galaxies, but when humanity recognizes its own limitations, and, as a result, causes that “God does descend from infinity to finitude, from boundlessness into the narrowness of the Sanctuary,” or:

All I could do was to pray. However, I could not pray in the hospital… the moment I returned home I would rush to my room, fall on my knees and pray fervently. God in those moments appeared not as the exalted majestic King, but rather as a humble, close friend.

While at prayer, the individual is constantly focused on his or her own inadequacy compared to the Divine Creator and his or her own limitations. The individual cannot be engaged in the battles of denomination supremacy, as he or she is paralyzed by his or her own smallness while attempting to pray.

Moreover, prayer is generally a uniquely unsuited vehicle for conveying specific, unique, or modern ideologies and beliefs. It focuses on requests and aspirations, not on statements of creed. The text of the Siddur also serves as a unifying tool for the Jewish people (given the enormous general similarity despite centuries of division and dispersal) and highlights what we have in common and not what we have apart.

Accepting Retreat in the Selection of a Siddur

As I begin to study the implications of this viewpoint, I am more and more convinced that the right Siddur for me is one that is perfectly ideologically neutral, which contains no hints to my views, ideologies, or perspectives. I prefer not to be reminded every few pages of how I differ, or am better than, or am inferior to, other Jews with other interpretations–and I prefer not to be distracted from my dialogue with the Creator by having to weigh each translation, footnote, or comment in terms of how much it conforms to my beliefs. Perhaps I will switch back to ArtScroll’s Siddur Chinuch, which has no translations and commentary and thus fewer opportunities for ideological bias, or the Koren Hebrew-only Siddur, which has fewer Modern Orthodox additions.

Prayer and Torah study are not the times to focus on how we differ from each other or to think about the victory of our philosophy over another; instead it is the time to think about the parts of Judaism that have never changed, those that are basic and simple, open and inviting to be defined by us in the moment as we amble through. And it would be a shame if we came to the point where every movement and sub-movement must choose a unique Siddur that uniquely reflects them. Perhaps I will accept the greatest defeat of them all and just use an old Hebrew Publishing Company Siddur or an old family Siddur from decades ago, which still has a prayer for the czar or the king and queen and Yiddish instructions, bound together by layers of black and silver duct tape.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.