Zev Eleff

“Zevi, David, Ben, and Joey,

Stick with the O’s.

Listen to Mom.

That’s what I did.”

In the summer of 1988, Rabbi Mordechai Nissel spotted a novelty item near the cashier’s station at a Jewish book store in Baltimore. The opened box revealed a bounty of cellophane-wrapped rabbi cards, each one retailing for just about 80 cents a pack. The fourth grade teacher was on vacation, almost 400 miles away from his classroom in the Providence Hebrew Day School. But his mind was on his students and the cards’ clever slogan captivated him: “Collect Full Sets. Trade With Friends, Learn About Torah Leaders.” The scheme was a simple one to decode, no Talmudic logic needed: revere rabbinic superstars, not baseball all-stars.

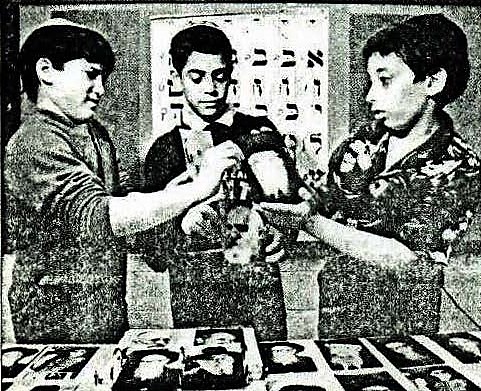

- Young students studying and trading “gedolim cards” at the Providence Hebrew Day School.

Rabbi Nissel was unsure. Could rabbi cards become a denomination of classroom currency, a reward for good behavior and test scores? The store manager informed him that the rabbi cards were all-the-rage in Baltimore, especially among 8-15 year-old boys. Nissel remained unconvinced. After all, the Baltimore Orioles were downright woeful. They had begun that season a dreadful 0-21. The season-long slump was surely enough for local Orthodox youngsters to abandon baseball cards for any alternate card collecting hobby.

But the phenomenon had moved beyond the Chesapeake. Rumor had it that eager boys had already purchased packs and packs of the Torah Personalities cards and that its creator, Arthur Shugarman, was planning a larger second series. The out-of-town customer was still incredulous. Then, the manager informed the patron that he was authorized to offer a half-price discount to Orthodox day schools. Nissel was sold. He brought a case of cards back to Rhode Island.

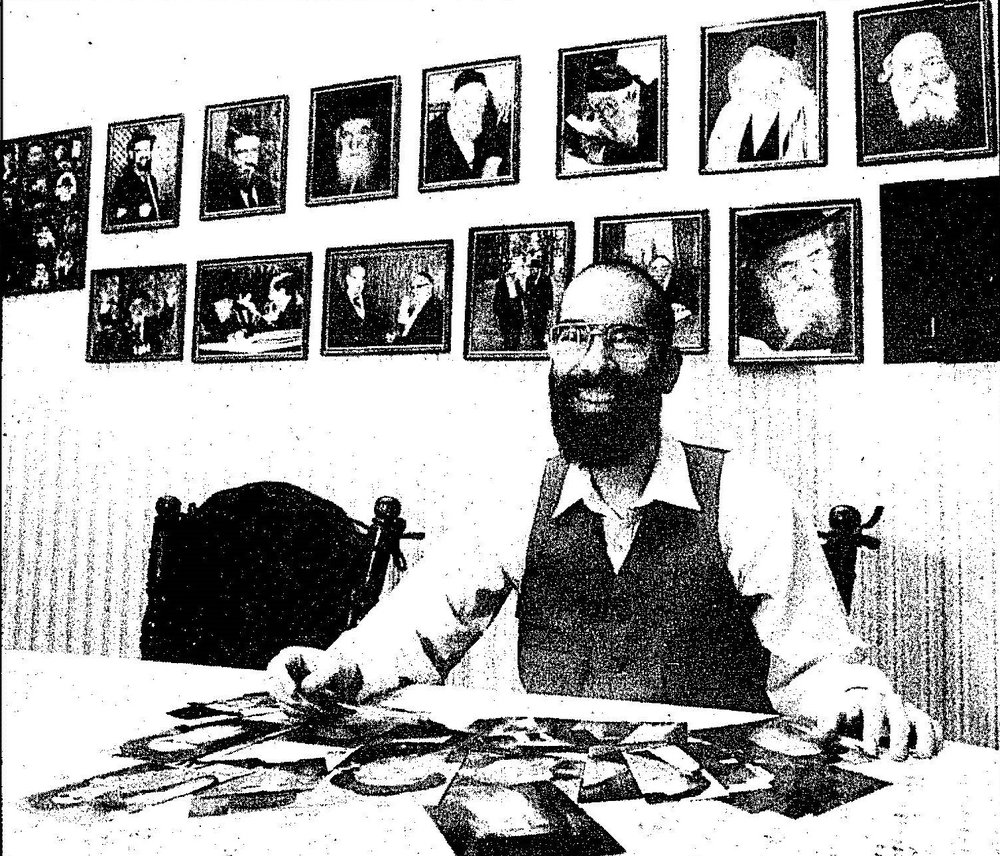

- Arthur Shugarman, the founder of Torah Personality Cards, displaying some of his collection. Before launching his “Gedolim Cards,” Shugarman was a heavily-invested baseball card collector and a devoted Baltimore Orioles fan.

Sure enough, the first 36-card series produced by the non-profit Torah Personalities, Inc. sold out in about six months. Partnering with a well-to-do kosher candy distributor, Shugarman sold 400,000 packages in a variety of Orthodox-dense locales. In Miami, for example, the owner of Judaica Enterprises found it “unbelievable how many calls I’ve been getting about the rabbi cards.” He therefore seized on the demand and ordered 288 packs of Shugarman’s trading cards. Concomitantly, a Judaica dealer in Detroit estimated that among the 10,000 Orthodox Jews in his area, perhaps a little under two-thirds constituted the considerable market for rabbi cards. The principal of a day school in Philadelphia corroborated all of this in terms that her young students might have used: “The Gedolim are very popular, very hot.”

What accounted for this success? The card inventor shot down any claim that his was a lofty mission to synthesize Judaism and American culture. In fact, he would have probably played down his role as an “inventor” altogether. Shugarman was the first to admit that his product was not the stuff of sheer innovation. “In New York City,” he once told an interviewer, “the selling of pictures of rabbis had gone on for some time.” Legend had it that a so-called “Yarmish” had more than 100,000 postcard-sized rabbi images in his Flatbush home.

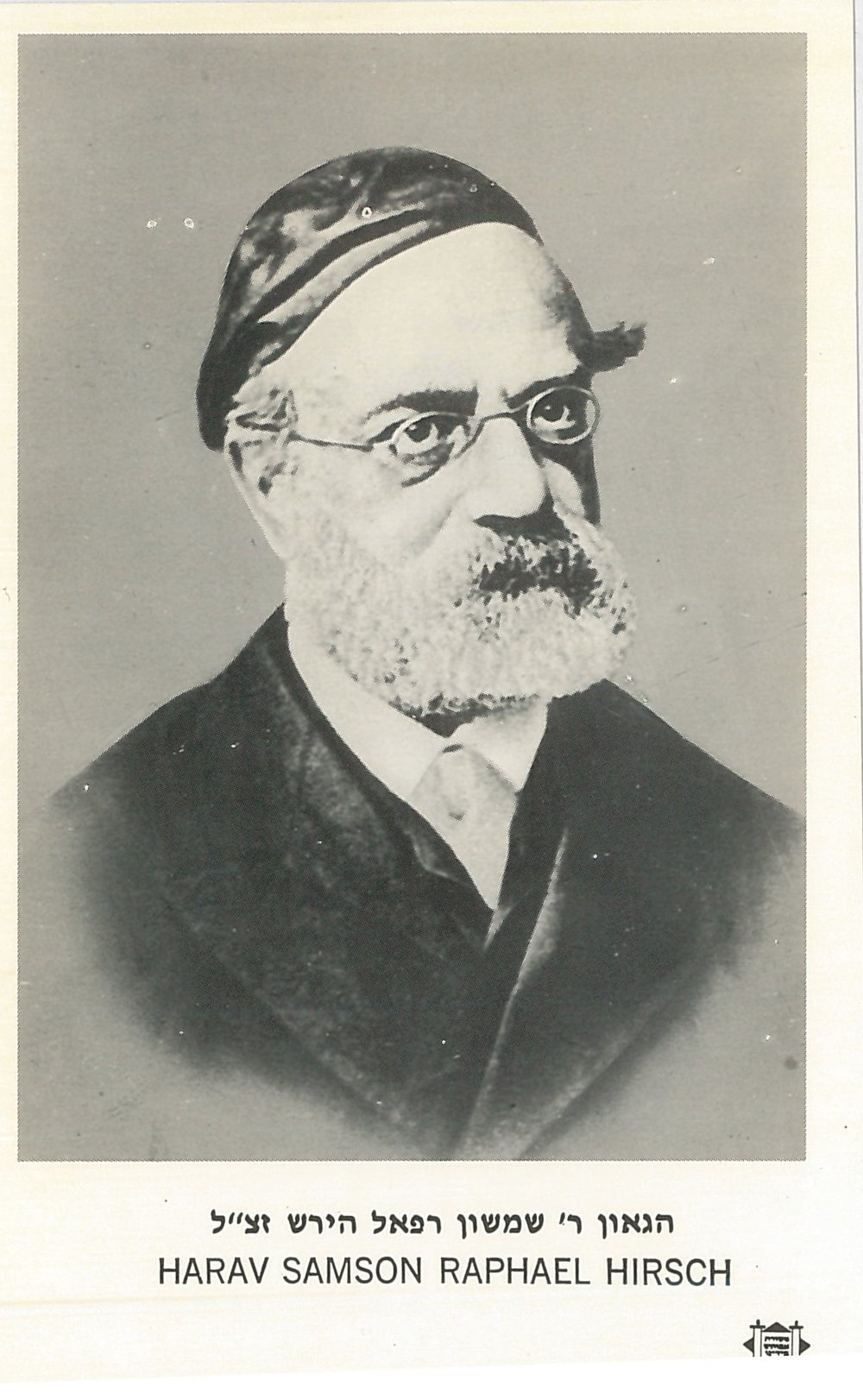

Shugarman was a 34-year-old who sported a thick dark beard that seemed to age him, and to underscore a sense of shrewdness about him. He knew his market well. In 1980, the youth division of the Agudath Israel of America produced a 35-card series of Photocards of Gedolei Yisroel,” or the “great ones” of Israel. The set featured black-and-white cards of deceased European-born rabbis, all at one point or another institutionally connected to—22 sat at one point on the “Council of Torah Sages”—or politically in sync with the Ultra-Orthodox movement. The Agudah provided a brief biography on the back of each card, sometimes to justify the inclusion of some gedolim into this prestigious collection. Consider the pithy text that accompanied Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch’s portrait: “Met the formidable challenge to the very basis of Jewish living posed by the ‘modern era’ with the religious philosophy of ‘Torah Im Derech Eretz.’ This maxim was the proclamation of the sovereignty of the Torah within any given civilization. Author of ’19 Letters,’ ‘Choreb,’ and commentary on Chumash and T’hillim.” The transformation of Hirsch into an anti-modernist was dubious, of course. His separatism and staunch opposition to liberal forces was unquestionable, thereby affirming his status, according to the card’s “statistics,” as a “Forerunner of Agudath Israel.”

Overseas, the most fervently righteous in Israel also collected. In the mid-1980s, Shmiel Shnitzer’s Photo Geula was one of a half-dozen stores in Jerusalem that peddled rabbi photos. The clerical photographs were not serialized or systematized like the Agudath Israel brand, just well-disseminated images of rabbis usually snapped by photographers at public gatherings, perhaps at a circumcision or wedding. Hardly a hindrance, the informality of these pictures added to the intrigue. In Shnitzer’s shop, most images were sold for the shekel equivalent of a dollar. Some, though, were slightly more expensive. In particular, hassidic rabbis garnered much interest. For a time, young yeshiva men paid top dollar for a picture of the Lubavitcher Rebbe until too many copies were produced and flooded the market. The Amshinover Rebbe, who did not approve of his image commercialized in this manner, was perhaps the priciest photograph. Rabbi Avrohom Yitzchok Kohn—i.e., the Toldos Aharon—who strictly forbade the distribution of his portrait, was unavailable at Photo Geula. Instead, young boys acquired the Toldos Aharon in “seedier” places like in the back of the yeshiva study halls. Or, they might trade. In 1988, the going rate for a Toldos Aharon was a Rabbi Eliezer Shach of the Ponevezh yeshiva and the Sephardic kabbalist, the Baba Sali.

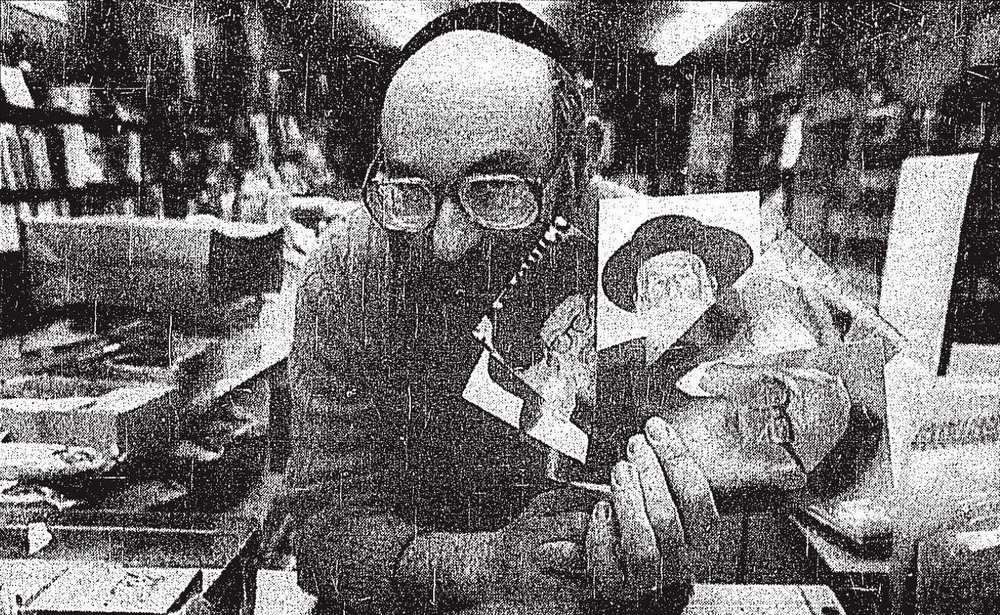

- A Judaica store proprietor in Detroit, showing off some of his in-demand rabbi cards.

Posthumousness also increased the value of a rabbinic photograph. For rabbi card dealers, this was no time to mourn. For instance, when the Lelover Rebbe passed away, the proprietor of Geula Photo “printed up 100 pictures of him right after I heard” and sold out the same day. In some morbid manner, the image commodified the deceased. The Lelover Rebbe was transformed into a Jewish saint, no longer a part of the “lowly” present generation. According to the Orthodox position, usually, contemporaries always pale in comparison to their forebears. In death, though, the Lelover Rebbe sat beside Moses, Hillel, Maimonides and the Gaon of Vilna. In a word, he was more than ever a part of Jewish history. No longer available to offer guidance and wisdom, he was in heaven’s hall-of-fame, in high demand for his immortal place in Jewish tradition.

Arthur Shugarman’s Torah Personalities cards did not compete with venders and photographers in the rabbi card markets. Instead, his cards joined them. For this reason, Shugarman printed cards in 4-by-6 inch format, much bulkier than a standard 2½-by-3½ inch baseball card, meant to fit comfortably in the palms of young collectors. To some, this made the rabbi cards appear amateurish, an awkward kind of collectable. Still, Shugarman preferred the Kodak-regulation images that better resembled the “real photographs” that had “caught on big” in certain Orthodox circles. The gimmick was sufficiently effective to convince one Orthodox educator to purchase the cards for students but who otherwise thought that the “importance placed on baseball cards and players in our society is absolutely asinine.”

Torah Personalities cards were also blessed with propitious timing. Between 1975 and 1980, the number of “serious” baseball card collectors rose from 4,000 to 250,000 in the United States. By the close of the decade, three to four million Americans collected sports cards to some degree or another. The exponentially rising interest in the collectables inspired upstarts like Fleer and Upper Deck to more vigorously complete with the longtime standard-bearer, Topps. Shugarman launched Torah Personalities in August 1988, in the midst of the trading card boom.

For some, the rabbi cards were sufficient to displace baseball stars. In Baltimore, a middle-schooler happily bequeathed his baseball cards to his younger brother, since rabbi cards were “more interesting.” Little Yossi Brull accepted his sibling’s collection, but also grew fonder of rabbi cards. Sixteen-year-old Avrohom Rosenberg of Philadelphia grew unimpressed with the adoration of his sub-mediocre Phillies and its roster full of men of “physical capabilities and nothing great.” In contrast, claimed the teenaged Rosenberg, “rabbi cards give us something to look up to.” Other boys did not abandon sports cards but treated their rabbi cards with a decided degree of reverence. Children did not flip them or ding the corners. Two youngsters, also of Philadelphia, vowed never to trade rabbi cards for baseball cards, though rumor had it that there were “kids who have.”

Far more often, Orthodox children traded endogamously, rabbi card for rabbi card. The editors of Time were correct that the “most coveted” card was Rabbi Moshe Feinstein of New York’s Lower East Side. His trading card likeness was unavailable for a one-to-own swap, say, for a Rabbi Ovadia Yosef or a Rabbi Mordechai Gifter card. Interested collectors were prepared to offer two or three rabbis for a Feinstein, who sat comfortably and unquestionably atop the Orthodox rabbinic power rankings.

Shugarman was aware of the fast-growing market for trading cards. He knew it well from a previous life, before he entered the Orthodox fold. As a youngster in Baltimore, Shugarman collected coins, figurines, and stamps but his truest passion were baseball cards. Hometown hero Brooks Robinson was Shugarman’s favorite card to collect. They shared much in common. Both were mild-mannered, dependable men. Robinson used those qualities to become the “Human Vacuum Cleaner,” the most dependable third-baseman in professional baseball. At 5”5, Shugarman was in no position to succeed his idol, so he found his way into accounting, an honorable profession for a trusty kind of man.

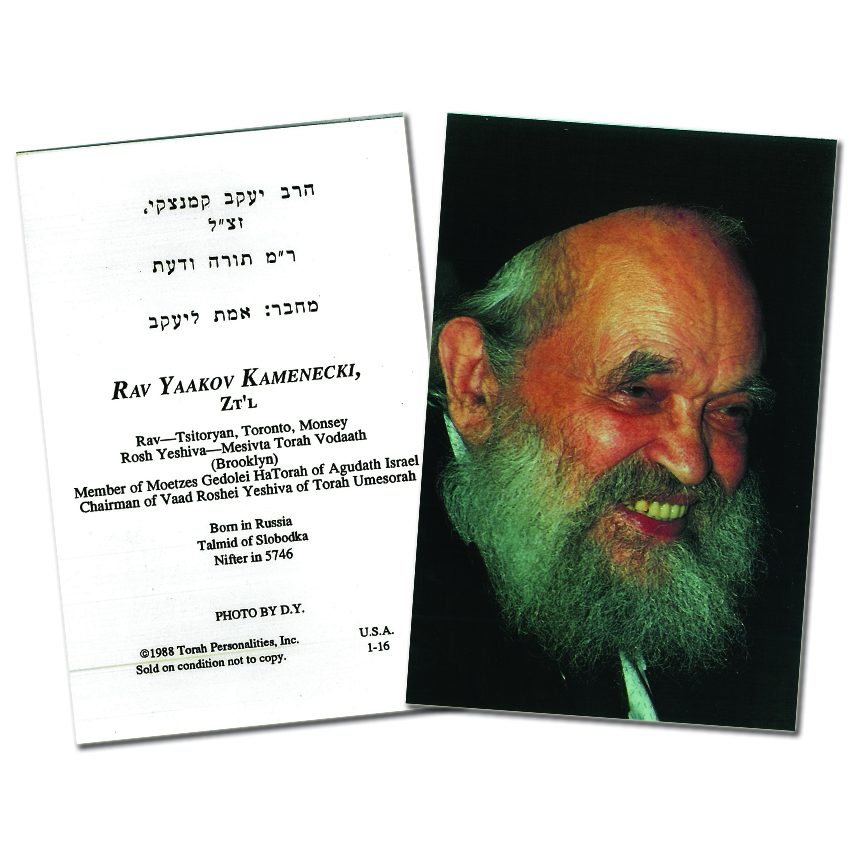

The idea to fashion sets of rabbi cards had percolated for some time. Probably as early as 1982, when, in his late-twenties, Shugarman sold his large stash of baseball cards. It was not a prerequisite to enter the “Strictly Orthodox” fold (Shugarman preferred this moniker over “Ultra-Orthodox”), but the decision to unload his collection made it easier to transition to a new environment. Shugarman had replaced Brooks Robinson for Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky. Like Robinson before him, Kamenetsky was revered by Shugarman more for the sage’s piety and humanness than his super-scholar-stats.

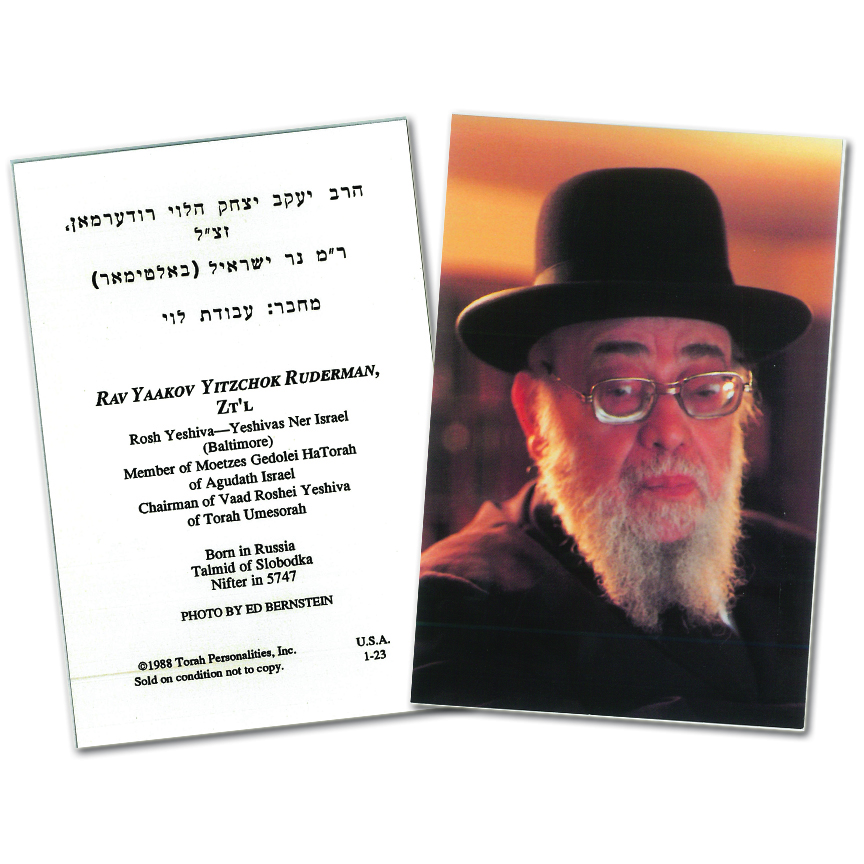

Rabbi Kamenetsky had recently died. He wasn’t the only one. Rabbis Moshe Feinstein, Yaakov Ruderman and the Steipler Gaon had all died as Shugarman was planning the production of his rabbi cards. Upon the death of Ruderman, the last of this group, one observer noted in a private letter to his successor at Ner Israel in Baltimore that “Rav Ruderman was the last of that small coterie of European Torah giants.” It was a bona fide crisis. This, then, reflects Shugarman’s good timing. Orthodox Jews in the United States had recognized that they were vulnerable and bereaved. Their children and students could no longer learn from the famed rabbinic leaders. They could, however, interact with and learn about the rabbis on the back of each card. For the collector this was a form of retrieval. For the distributor, it was a religious commodification.

Shugarman made the most of this dire moment. The first series of Torah Personalities featured 15 dead rabbis, and all but two had passed away within the past decade. Among the 21 living rabbis depicted on the cards, most were quite aged and had just a few more years to live. The Baltimore-native consulted with local rabbis and some in New York about which rabbis to include in the first trading card installment. Shugarman insisted that he would only consider color images, thereby excluding scholars from previous centuries. Scholarly output was also a consideration. Most of all, Shugarman, who still had that “collecting blood,” sought out popular rabbinic men.

Shugarman was satisfied with his initial selection. Besides, he had amassed hundreds of extra photos, enough, as it would turn out, to furnish another five series of rabbi cards. The analytics of the first set reveal the bias of the rightwing American Orthodox rabbis queried to assemble the rabbinic roster. Two-thirds of the carded rabbis flourished in the United States, as opposed to Israel. Just three were American-born. And, nearly half sat on the Agudath Israel’s rabbinic presidium.

Still, Shugarman thought that he had nailed it, offering a wide swath of rabbinical personalities. “We tried to get a little bit of everything,” he said with pride. “Hasidics, Sephardics, Lubavitchers, and we tried to stay as nonpolitical as possible.” To be sure, Shugarman included images of the Bostoner Rebbe, Lubavitcher Rebbe, and the Satmar Rebbe. Luminaries like the Babi Sali and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef fulfilled the Sephardic quota.

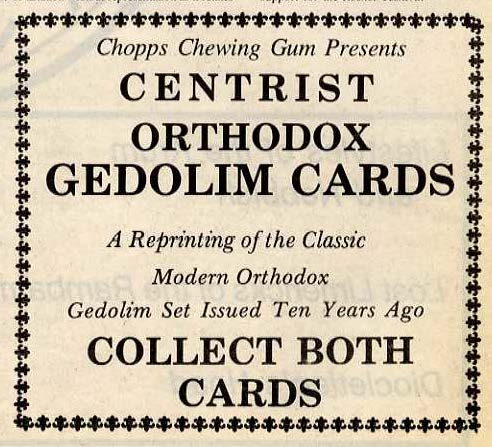

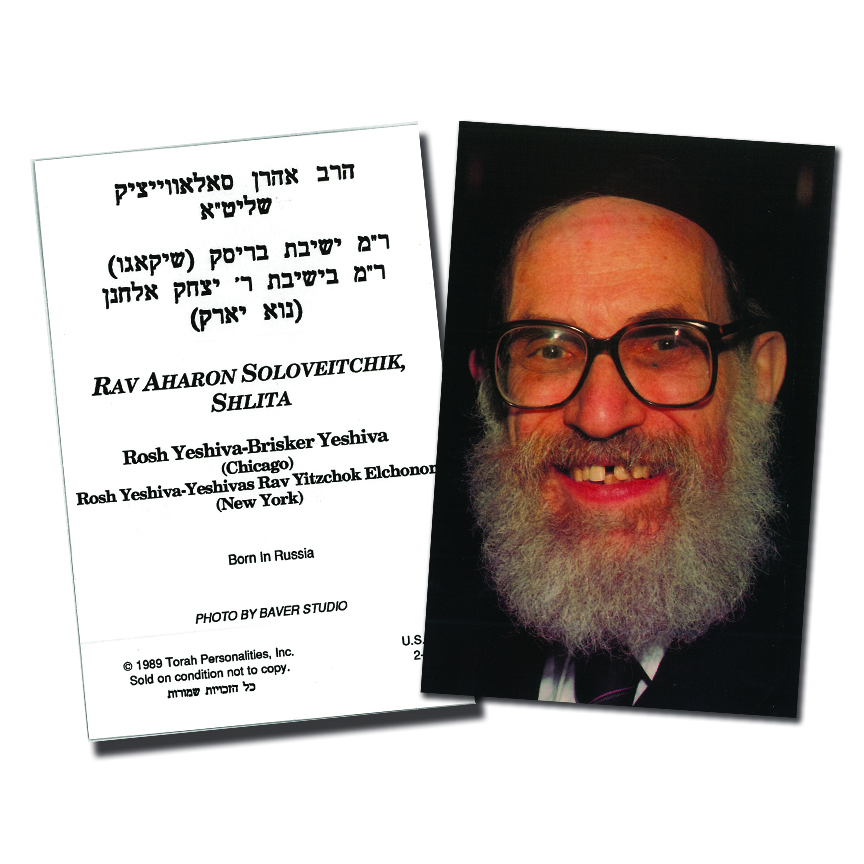

However, the series failed to include anyone associated with the modern-leaning Yeshiva University. The students at that school had a bit of fun with that in the Purim lampoon edition of its campus newspaper. A mock-advertisement announced the appearance of “Centrist Orthodox Gedolim Cards.” Readers were encouraged to “collect both cards.” Actually, the second set published in 1989 featured two YU personalities: Rabbi Dovid Lifshitz and Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik, both more “rightwing” than other personalities associated with the school. However, this probably did little to attract the interest from the so-called Centrist Orthodox community. This ilk generally eschews Da’as Torah, or the supreme—if not infallible—authority of the rabbinic elite. Quite Protestant in orientation, the same goes for rabbinic pedestals and anything that might be construed as rabbi worship. Rabbi cards, therefore, did not move these folks as it had adherents of Shugarman’s “Strict Orthodox” way of life.

Others also felt uneasy about injecting Jewish holiness into the collecting enterprise. A Reform rabbi in Philadelphia described it as “utter nonsense.” An Orthodox clergyman joked that “there’s nothing wrong except that it’s a form of idolatry.” From the opposite perspective, an Orthodox woman from Long Island opined that it did not redound well to rabbis to be associated with other athletes and celebrities often depicted on trading cards. In her words, rabbis had been “grouped in together with ugliness, proving beyond a shadow of a doubt the argument against the distribution of these cards.” The Torah Personalities operation also betrayed a heightened level of modesty that was connected to the rabbinate. In fact, some, like Rabbi Elya Svei of Philadelphia, were reluctant to lend their likenesses to the project, but acquiesced after it was impressed upon them that the cards carried a certain educational value.

Nonetheless, the enthusiasts generally overmatched the critics. To date, Torah Personalities Inc. has sold some three million rabbi cards. Its curious achievements have been documented in New York Magazine, Sports Collectors Digest, Sports Illustrated, and Time. In the 1990s, imitators such as Torah Cards and Torah Links Cards emerged on the growing market of Orthodox collectables. In 2000, Ben Stiller’s character in Keeping the Faith boasted of his “Heroes of the Torah” card collection.

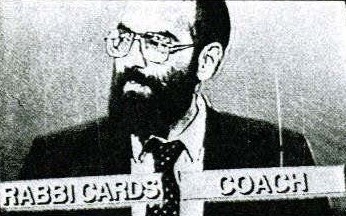

- Arthur Shugarman during the 1991 taping of To Tell the Truth

A collector to his core, the soft-spoken and humble accountant from Baltimore saved the magazines clippings, as well as many articles from the local Jewish newspapers. After Shugarman passed away in 2011, his brother, Laibel, who had assisted his older brother from the early goings, took over the Baltimore-based operation. For both Shugarmans, their proudest moment occurred on one 1991 installment of the popular NBC television gameshow, To Tell the Truth. The show’s producers were flabbergasted by the quirkiness of the rabbi cards in American culture and made accommodations for the Sabbath-observing Arthur Shugarman to tape on Sunday rather than the usual Saturday slot. Per the rules of the game, Shugarman told two stories. In one, he posed as himself, the creator of “unique trading cards, like baseball cards, with pictures of well-known rabbis.” The second was a fib, a tale in which he assumed the role of a Henry Higgins-like New York-style “dialect coach” hell-bent on ridding Jews of Brooklyn accents. To the uninitiated, both stories were outrageous. The panel of four celebrity judges found the latter account slightly more plausible than the first and Shugarman walked away with a $1,000 prize for his efforts in deception.

After the show aired, Shugarman remarked that “people didn’t know what to make of me. They thought I was a prop.” He knew better, though. Arthur Shugarman was the popularizer of a righteous commodity. Like other goods, his was traded, sold, and collected. His, however, doubled as two-dimensional fragments of tradition that could fit somewhat awkwardly into the palm of a young Jewish child’s hand.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.