Stephen Denker

These past six years, I have been helping my son-in-law’s father, Bert Katz, write his memoirs about his home in Nentershausen, a small rural village in the State of Hessen near the geographic center of Germany. In the Fall of 1940, when Bert’s family fled Germany to safety, Nentershausen had fewer than 700 residents. His family escaped Germany through the Soviet Union, Japan and across the Pacific Ocean to Quito, Ecuador. He was 10 years old.

Although many historians have focused on the events that occurred on the night of November 9, 1938, the Kristallnacht pogroms were neither one twenty-four-hour event nor confined to cities. Kristallnacht began earlier than in other places in the smaller villages of Hessen, and extended over the four days of November 7-10, 1938. [Alan Steinweis, Kristallnacht 1938, Harvard University Press, 2009.]

Throughout Germany, violence erupted in hundreds of communities, the vast majority of them small villages with only a handful of Jews. The list of places in which pogroms occurred includes many unknown even to experienced scholars of German history — villages such as Nentershausen. In all these small villages, Germans were prepared to inflict violence upon their Jewish neighbors. The number of rural Jewish families had dwindled since the Nazis had come to power. Unfortunately for the few who remained, they and their small synagogues were easy targets on Kristallnacht.

The pretext to initiate the pogroms was the assassination attempt on the German diplomat Vom Rath in Paris. In “response,” Nazi thugs set fire and destroyed synagogues and looted Jewish-owned stores and homes. Many Jews were terrorized or beaten, and some were even murdered. In the aftermath of the pogroms, more than 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps, including Bert Katz’ father, Willy.

The first destructions occurred late in the evening on November 7, in Kassel. Prompted by a local Nazi official, the riot began when a mob, mostly made up of SA and SS members, broke into and destroyed a Jewish restaurant, then a synagogue, and then some twenty Jewish businesses.

The next night, November 8, 24 small Hessen villages, including Nentershausen, were also the scenes of violence. Mobs led by Nazis in the village entered, looted, and desecrated—but did not destroy—the Nentershausen Synagogue. The prayer sanctuary was ransacked, its contents thrown out into the street. Torah scrolls and sacred books were burned.

The vandals would not set fire to the building itself, as that would jeopardize neighbouring Christian-owned buildings. Instead, they tried to collapse the entire building by sawing through its supporting central column. However, their motorized saw stalled and its blade became stuck during the attempt. With their goal unrealized, the vandals fled, fearing the building would collapse on them.

After trashing the synagogue and desecrating its religious contents, the mob continued their destruction in Jewish homes. They looted and trashed both the Katz’ living quarters and their shoe shop. Inside the Katz living space, the dining room and the kitchen were smashed. The mob looted crystal, pots and dishes. Even wet laundry was stolen.

The mob leader and instigator was the local Ortsgruppenleiter (Nazi Leader) Konrad Raub (whose surname, ironically, means “loot” in German). Raub commanded blacksmith Karl Gebhardt and house-painter Heinrich Windedemuth to engage in the robbing and pillaging, but both declined—“They would not join such a thing!”

Earlier in the morning that terrible day, Georg Wettich had boasted to shoemaker Heinrich Stein—who himself did not participate in the violence—that, “In the evening it would go badly for the Jews.” While leading the plundering of the Katz’ home, Wettich opened the drawers of Willy’s business desk. Among other objects, he took the shoe business record book and loudly declared in Stein’s presence that he would now see “who had done business with the Jew, Katz.”

The Katz family sought refuge in the attic while the mob looted the house and shoe shop below. Behind the door on the top of the stairs, the family piled furniture and other heavy items. The looters discussed setting the house afire. Had they gone through with the plan, the hiding place would not have helped much. Bert was terrified, recalling a massive barn fire he had seen when he was six years old. Fortunately the mob was talked out of it by their neighbors, whom Bert believes knew that the family was hiding inside the house.

To protect his family in the attic against harm and ensure the mob would not change their mind, Willy went out of the house with his four-year-old twin sons. Once outside, he was kicked by one of his own apprentice shoemakers, Justus Kesten, who also had played a leading role in looting the synagogue, and was beaten by the mob despite the neighbors’ protests.

Mayor Schwanz, Nentershausen Police Sergeant Zimmermann, and several neighbors were brave men, especially for 1938 Nazi Germany. They were not afraid to help the distressed Nentershausen Jewish family. (Earlier, the Nazis had created new official police hierarchies and roles throughout Germany. Local police, even those in Nentershausen, were officially under national Nazi command, including Zimmermann himself.)

In his reparations affidavit, Willy wrote, “That we came away with life itself, we owe to Mayor Schwanz, the shoemaker Ewald Moeller and the carpenter Johann Bergling. Herr Schwanz was so ashamed [sic] about this painful act of vandalism to our home and to our furniture he sent a carpenter, who made enough makeshift repairs of our furniture for us to use.”

The day after the pogrom, Zimmermann recovered the shoes that had been stolen during the lootings. The local Nazi Leader Konrad Raub, also a shoemaker and a business competitor of Willy, had over 120 pairs of stolen shoes and other stolen shoe-making equipment in his possession. (Self-aggrandizing theft was a common thread in Kristallnacht looting.) They were seized and delivered to the Mayor’s office, then returned to Willy.

After Kristallnacht in Nentershausen, Bert Katz’ parents thought they would be safer in a large city. His father had relatives living in Frankfurt, but did not have an automobile to travel there. Willy therefore contacted his second cousin Norbert Bloch, who had his own car. Bloch came and drove the family to Frankfurt during the night of November 9, an action which saved his life. Later Bloch found out that he was on a Nazi list of persons to be arrested and murdered on Kristallnacht, but the authorities could not find him since he was away rescuing family members.

As the Katz family embarked on their drive to Frankfurt, little did they suspect that Kristallnacht would precede them. Bert vividly remembers their family’s great shock and grief when they arrived in Frankfurt on the morning of November 10 seeking safety, and instead saw synagogues burning.

Willy decided to return to Nentershausen alone. But close to home, he was recognized and arrested at the railway station and taken to Kassel. From there he was transported to Konzentrationslager, Buchenwald (60 miles east of Nentershausen) and imprisoned. Willy was held there from November 12, 1938 until December 10, 1938. He was released earlier than most prisoners since he had served with distinction and honor in WWI, receiving medals for his valor. When he was released, he was warned that he should leave Germany as soon as possible. “If he did not, he could be re-arrested. He would not leave Buchenwald alive again.”

Despite their diminishing numbers, Jewish community life in Nentershausen continued. Then on May 30, 1942, the last remaining Jews in Nentershausen were taken to Kassel. From there they were transported on June 1, 1942 to the Majdanek death camp.

At Peace

After WWII, Willy returned to Nentershausen: to the place he was born and raised, had married and had started a family.

Many long years ago, local farmers had tried to persuade and reassure him, “Willy, stay here, it will not last long with Adolf, nothing is as bad as it looks.” But it was.

In 1980, at the age of 82 and living in Israel, Willy made his last visit to Nentershausen. He and his wife Martha still had Christian neighbors and friends in Nentershausen. “They were good people, very good people.

Of course, he had not forgotten who had been the the ringleaders and looters during Kristallnacht. He still could recall them all by name. School classmates of Willy had included Konrad Raub. Willy visited the former local Nazi leader, who had lost his only son in WWII, on his deathbed. They spoke for the last time without bitterness.

Back in his Petah Tikvah living room, Willy smiled a little. “We all have to thank Adolf. I would have preferred to have stayed in Nentershausen, surrounded by sons and grandsons and great-grandsons, speaking the familiar local Hessian dialect.”

A thousand memories, good and bad, still bound Willy to the birthplace where he knew every tree, every lane and every family. The graves of his mother, grandparents, schoolmates and childhood friends are all in Nentershausen. Nentershausen was his home.

The Nentershausen Synagogue Restored

In her 2007 book Synagogen und Jüdische Rituelle Tauchbäder in Hessen (Synagogues and Jewish Ritual Baths in Hessen), Thea Altara counted the number of synagogues that survived Kristallnacht. In the early 1930s there had been 439 synagogues in the State of Hessen. Of these, 40 percent were destroyed during the Kristallnacht pogroms, 16 percent were demolished after 1945, and only 44 percent of the synagogue buildings still exist, but in degradation or another use.

The Nentershausen Synagogue building had survived, but could no longer be used. Axes had obliterated the gold inscription on the wooden lintel above the Torah Ark. Today this desecrated lintel is on permanent display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

After Kristallnacht, local resident Johannes Krause bought the synagogue building from the Municipality together with the adjacent Hirtenhaus (shepherd house) for 600 Reichsmarks. He converted the former synagogue into a garage for his trucks, cutting large openings in the street-side of the building to allow the large vehicles to move in and out. His family still owns the land today.

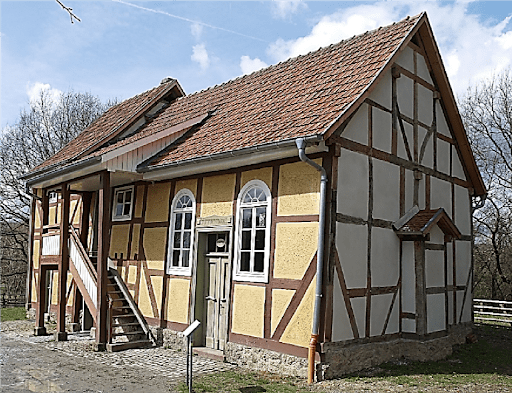

In 1987 the Nentershausen Synagogue building was sold for one Deutsche mark, dismantled, and moved to the Freilichtmuseum Hessenpark (Hessenpark Open-Air Museum) in Neu-Anspach, a city north of Frankfurt. Founded in 1974, Hessenpark is a full-scale re-creation of rural Hessian villages, with grounds that include over 100 original buildings which have been dismantled from their original locations and rebuilt there.

On July 16, 1996, the reconstructed Nentershausen Synagogue with its original 1925 decorations, colors, furnishings and Mikvah was rededicated. The dedication ceremony took place in the presence of many prominent German government and religious dignitaries.

The Hessenpark leadership used the opportunity to issue a mutual challenge:

Today this small, reconstructed synagogue bears testimony to the Jewish life that once existed before the pogroms of the Nazi era. Although it is in its original form but not used as intended, it will help others learn about the reasons that led to this diminished reality.

To prevent the disgrace of repetition, we want to keep alive in our memory that the dark epoch in German history is never forgotten. We want to keep alive in our memory, in our historical consciousness, to learn from yesterday for today and for tomorrow. We want to keep alive the memory to help us handle the dark periods of our history here. Jews had lived in Nentershausen nearly 300 years.

And what about today? Responsibility remains. We cannot escape our history. We have to acknowledge it. What to do? There must be a lively dialogue with the Jewish people. We must accept our responsibility for the Jewish people, for the people of Israel.

We also need solidarity with all working to remove persecution. We must not retreat into a comfortable private and silent life when injustice occurs. We have a special responsibility. We must defend against any injustice, against any cruelty. More so after the Holocaust no one is allowed to stand on the sidelines when humanity is at stake. We must always be alert for the bad things that can happen again. The evil spirit is still stirring again in many corners.

If we stand up, then this day of remembrance of the horror, grief and shame can better be a day of promise.

The construction of this humble, beautiful synagogue in Hessenpark is a modest but important contribution to memory, to exhortation, to knowledge and to hope.

November 4, 2018

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.