“The Pioneer of Hasidic Literature.”

“The most important Zionist (at the first Zionist Congress).”

“An undiscovered genius.”

“Defender of Kabbalah and the Masorah.”

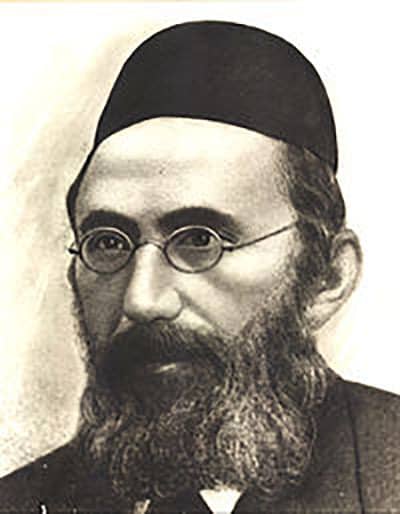

Yes, a single man was called all of these things. Ahron Marcus, whose 101st Yahrtzeit is observed today, might be the most interesting man of the turn of the 19th century you’ve never heard of. He was truly a man of paradoxes: never ordained, but often called rabbi; a Hasid who supported Herzl; a student of archaeology and the ancient world who vehemently opposed the documentary hypothesis; a devout adherent of Hasidism who simultaneously provided historical and psychological analyses of his religious world.

Ahron Marcus (1843-1916) was born in Hamburg and recognized in the German Jewish community as a prodigious illuy in learning at a young age, studying with students of the famed Rabbi Isaac Bernays. Aside from his traditional learning, in his teenage years he was educated as an enlightened maskil, becoming well-versed in philosophy, history, and foreign languages. The details are somewhat murky, but on his sister’s account he suffered a crisis of faith at that time, and was subsequently spurred to join a Hasidic yeshiva, where he remained for several years, later marrying into a Hasidic family. He immersed himself in various Hasidic courts, finally joining the Tiferet Shlomo, R. Shlomo Rabinowitz of Radomsk, and settling in Krakow. It is important to note how unique this trajectory is, as it was extremely uncommon for intellectually oriented Jews to shift into a Hasidic lifestyle and worldview at that time.

As noted, Marcus’ accomplishments over the course of his life were manifold. He was a prolific author across many fields (sometimes writing under the alias Verus, meaning Truth). He wrote a book on psychological and philosophical matters in Hasidut based on Eduard von Hartmann’s psychological work on the conscious and subconscious (Vienna, 1888). Among his findings (which were discussed in this recent article by Prof. Shalom Rosenberg), he argued that miracles can be understood on the basis of the power of suggestion. His training in history and ancient languages supported his study of the ancient period and Judaism, as he published several works, including a series on Flavius Josephus und seine Zeit, studying the great Jewish historian Josephus in historical context, and Kadmoniyot (Krakow, 1896-97) on Mesopotamian archeology and its ramifications on biblical and rabbinic Judaism, where he used the Tel el-Amarna letters to support the biblical account of the situation in Egypt and Canaan. Fusing his philosophical/psychological and historical/linguistic interests, Marcus also wrote a work on the history and psychology of language entitled Barzilai, or Language as the Writing of the Soul (Berlin 1905f.; Heb. 1983), which includes questions in comparative Semitics and the development of the Hebrew language (including the claim that the Semitic root is originally bilateral), but also more traditional and psychological perspectives.

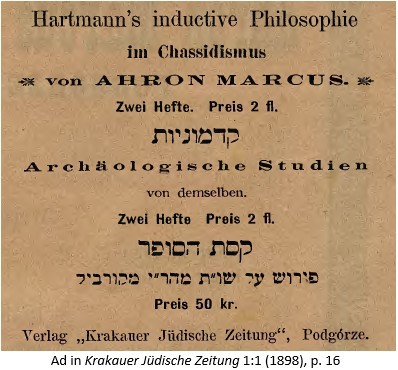

Marcus’ scope of writing was not limited to the adventurous, however. He also authored several traditional Torah studies, including an extended commentary on the Bible and the Mishnah entitled Keset ha-Sofer (Krakow 1912f.), which was mostly lost in the ravages of the Holocaust. Additionally, he published an edition of R. Jacob ha-Levy’s Shu”t min ha-Shamayim, providing his own substantive introduction and commentary, also entitled Keset ha-Sofer (1895). In addition, Marcus published numerous monographs, on topics as varied as Darwinism and biblical criticism (which he vehemently opposed). He wrote on political matters as well, founding the monthly Krakauer Jüdische Zeitung in 1898 and writing prolifically for that journal, primarily on Zionist issues.

Indeed, Marcus was very active in the early Zionist movement. Joshua Shanes’s article, “Ahron Marcus: Portrait of a Zionist Hasid,” lays out his fascinating trajectory in that movement, which is presented here. Marcus was first drawn to Religious Zionism in 1882, joining the Hibbat Zion movement and establishing the Rosh Pina society that supported the Jewish settlement in the Holy Land. In doing so he followed the Ruzhiner and Belzer Hasidic courts, as he did in dialing back his support in the wake of the Shemita controversy of 1888. Along with Nathan Birnbaum, he was the first chairman of the local Chovevei Eretz Yisrael society.

However, Marcus’ Zionism reached its peak, in a sense, upon his reading Theodor Herzl’s Der Judenstaat in 1896, on which he lectured on the following year. Breaking with Mahzikei ha-Dat, the Orthodox communal organization, Marcus spent the next four years in lengthy correspondence and personal friendship with Herzl, discussing theoretical matters but, most importantly, the possibility of bringing Eastern European traditionalists into alliance with the Zionist movement. Among Marcus’ attempts to convince his Orthodox confreres of the value of Zionism were his assertions that Herzl would not set up a secular state (despite Herzl’s clear assertions that he was opposed to establishing a theocracy). He offered robust praise of Herzl asserting that “The wisdom of God is with Dr. Herzl.” Marcus spent significant energies endeavoring to forge an alliance between his Rebbe at the time, David Moshe Friedmann, the Czortkower Rebbe, and Herzl’s Zionist movement, toiling in vain to set up a personal meeting between the two.

Ideologically, he combined a certain messianic view idealizing the potential restoration of the Jewish homeland with a down-to-earth position focused on uniting European Jewry around pragmatic alliances. Zionist nationalism should be uncontroversial, Marcus argued, because nationalistic loyalty is simply based on the extension of familial ties, and the ties of the Jewish family are strong. He drafted in support of Zionism both predictable leaders like the avowed Zionist R. Shmuel Mohilever but also the Tosafot Yom Tov (R. Yom Tov Lipmann Heller), building upon his position that the Temple may be built prior to the messianic era. Marcus attributed significance to the Land of Israel, but also saw the Land playing a pragmatic role, offering a means of solving the “Jewish Problem” in Europe. He even supported the possibility of a Jewish State in Cyprus when it seemed the Land of Israel was not on the table.

Unfortunately, the Hasidic-Zionist alliance was not meant to be. The meeting between Herzl and the Czortkower Rebbe never took place. By 1900 several Hasidic leaders explicitly opposed Herzl and his project, Marcus despaired of his great plan, and in 1912 was among the founders of Agudat Yisrael. The road was not travelled, and today a Hasidic ideological Zionism may sound oxymoronic to some.

Ahron Marcus’ contribution for which he is best known came neither in the realm of ancient history nor Zionist activism but in his role as the first historian of Hasidut. His book Der Chassidismus, the first academic work on Hasidism, which treated its various schools, is a well-cited work within both academic and traditional settings.

The book was groundbreaking, in several senses. Most significantly, it was the first systematic work written about Hasidut. While many Hasidic works had been published since the emergence of the Ba’al Shem Tov in early 18th century, this was the first scholarly treatment of the phenomenon. Furthermore, this was no naïve encomium to Hasidism; the book presented the historical development of the various schools, including drawing distinctions between them and considering their various contexts. This was a work of fairly critical scholarship, especially given the era of its publication. There is even a helpful introductory chapter on Kabbalah, as well as studies on pre-Hasidic thinkers such as R. Moshe Taku.

It set the stage by discussing and critically evaluating the various Hasidic groups, as well as by passing on various stories of Hasidic lore, many of which were picked up by later scholars of Hasidism. Der Chassidismus is often the first scholarly authority noted when considering the history of scholarship on a matter of Hasidic import. Although much literature has followed Marcus’ most famous book, and despite some of the challenges made as to the accuracy of some of the depictions, Der Chassidismus clearly was the founding text of the field of study of Hasidut, which served to crown Marcus as “the pioneer of Hasidic literature.”

Why have not so many people heard of Ahron Marcus? Part of the reason may relate to the limited available secondary material on his work. Given its position as the founding document in the study of Hasidut, Der Chassidismus has seen the greatest treatment among Marcus’ work enjoying multiple publications in Hebrew translation as well as scholarly treatments ranging from fairly early in the study of Hasidut (Moses Tsinovitsh, “R. Aaron Marcus – the Pioneer of Hasidic Literature,” 1933 and Gershom Scholem, “Aharon Marcus ve-ha-Hasidut,” 1954) to contemporary times as well (e.g., Moshe Idel, “Transfers of Categories: The German-Jewish Experience and Beyond,” 2015). Unfortunately, the Hebrew translation (Ha-Hasidut, trans. Moshe Shenfeld, 1980) is organized differently than the original, and censors several passages that had appeared in earlier edition (where Marcus was critical of particular Hasidic groups). This book has somehow not been translated into English, despite its significance as an early treatment of Hasidut, one that is informative of both its subject matter and its author. If someone would decide to translate this work, including the censored passages, it would go a long way in opening up Marcus’ work to a larger audience.

Marcus’ non-Hasidic publications have received even less attention. Several of his works have not been translated into either Hebrew or English, and many have not seen discussion in scholarly literature. Two recent exceptional treatments of his work are the study by Shanes on Marcus’ Zionism discussed above and a recent essay in Modern Judaism by Daniel Reiser, “The Encounter in Vienna: Modern Psychotherapy, Guided Imagery, and Hasidism Post-World War I” (2016) on psychological aspects of Marcus’ oeuvre (and that of other Hasidic thinkers).

The degree to which this revolutionary figure, replete with paradoxes, has been overlooked by contemporary scholarship is surprising. In a world where scholarship on Hasidut is flourishing, where absolute barriers blocking Haredim from academia are falling, and where Hasidut is often adopted by adolescents with secular educations, the story of Ahron Marcus becomes ever more prescient. Maybe this Hasidic Zionist promoter, first researcher of Hasidut, and Haredi scholar of ancient Judaism – a true polymath – will receive his due in the 102nd year since his passing.

Yehi Zikhro Barukh.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.