Henry Abramson

How Dr. Gershon Greenberg Trashed My Research

With a simple act of scholarly generosity, Dr. Gershon Greenberg ruined ten years of research and rendered a 500-page manuscript utterly worthless. That is the second worst thing that could have happened to my major study of the Piaseczno Rebbe’s Holocaust writings. The worst thing would have been to publish it.

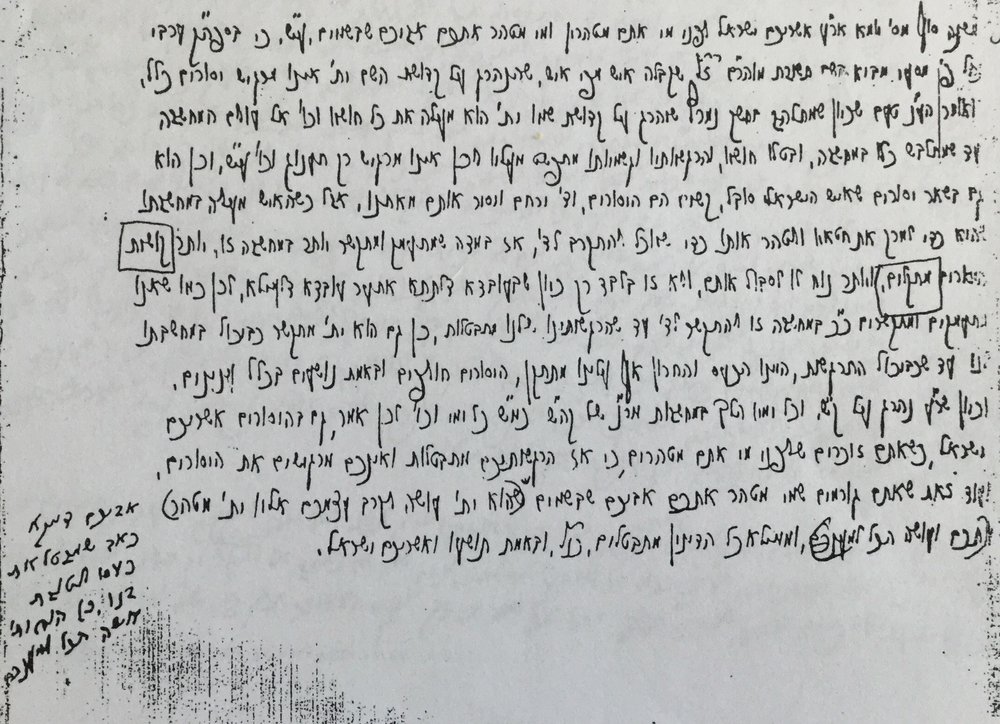

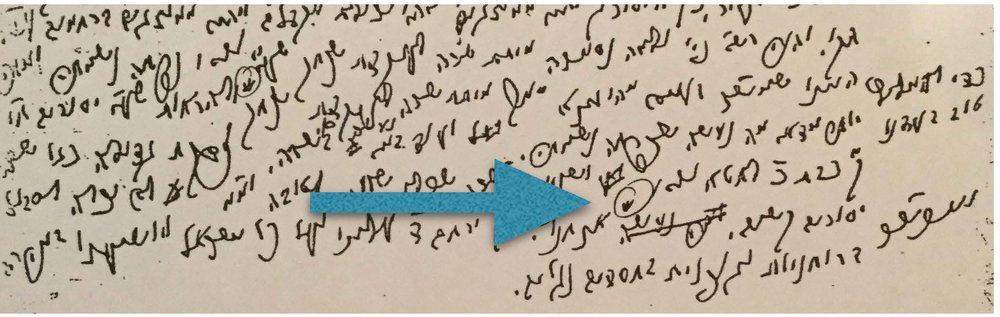

Entry by Avraham Radziner, the Rebbe’s personal copyist, with an annotation in the Rebbe’s hand.

Entry by Avraham Radziner, the Rebbe’s personal copyist, with an annotation in the Rebbe’s hand.

Dr. Greenberg, a prolific and well-respected specialist in Jewish religious responses to the Holocaust, was familiar with my work-in-progress on Piaseczno Hasidism from a number of articles I wrote and a seminar that we both attended at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The famed historian thought he was doing me a favor when he handed me a sheaf of photocopied pages of Hebrew script, facsimiles of the original manuscript housed in Warsaw’s Żydowski Instytut Historyczny. I accepted the senior scholar’s gift with gratitude, admiring the archival seal of the Institute and noting the simple handwritten title in Polish and Yiddish which translates into English as simply, “talks of Rabbi Shapiro.”

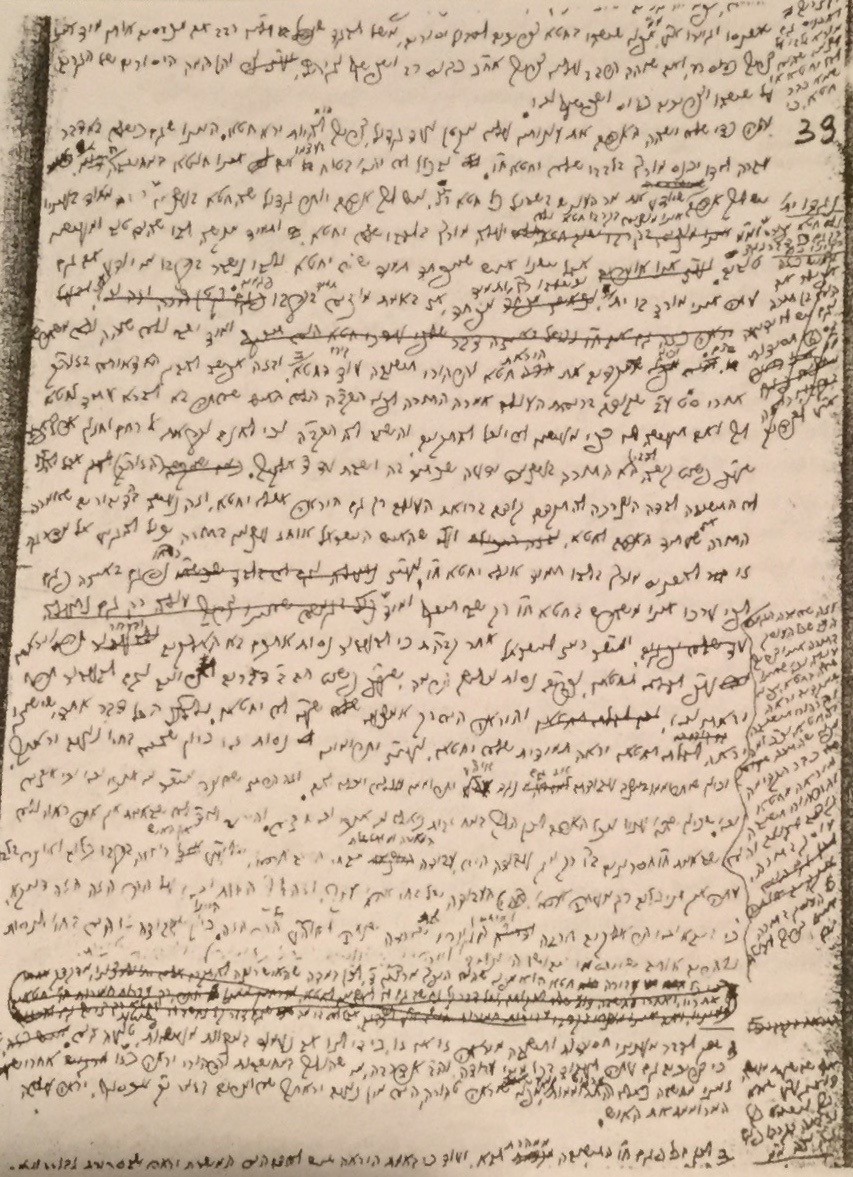

A typical entry in the Rebbe’s hand, with strikeouts, corrections, and annotations.

A typical entry in the Rebbe’s hand, with strikeouts, corrections, and annotations.

Leafing through the initial pages of even, regular Ashkenazic script, I imagined that the manuscript copy might provide a few useful illustrations for my magnum opus, or perhaps I would frame a page or two for the wall of my office (I still might). On closer examination, I realized that the first few entries in the manuscript were not written in the Rebbe’s hand, rather they were penned by his scribe, Avraham Radziner. His even calligraphy, incorporating the scattered annotations by the Rebbe, is faithfully represented in the printed version of the text published by the Council of Piaseczno Hasidim in 1960.

Radziner was killed within the first few months of the war, probably as a victim of the punishing bombardment that the Jewish quarter of Warsaw endured before the Nazi ground invasion. All later entries were recorded in the Rebbe’s cramped, rushed hand. Fortunately, the pious editors of the first edition completed the difficult work of deciphering the script, leading me to believe that my own research was enhanced but not seriously affected by Dr. Greenberg’s thoughtful gift of the manuscript copy. I could not have been more wrong.

A cursory comparison of the manuscript and the published text indicates the presence of a heavy, hidden editorial hand. The manuscript is marred by numerous strikeouts, corrections, and annotations, but their presence is belied by the smooth, fluid printed prose of the Rebbe. This is understandable in terms of the underlying intent of the editors—they wished to produce a clean, readable representation of the Rebbe’s thought, unmarked by the Rebbe’s prevarications over the correct phrase, deletions, or additions where the later insertion has consequence. It is telling, for example, that the printed edition lists two tables of contents: the first lists the sermons by their occurrence in the Torah and holiday cycle (e.g., three entries for Rosh Hashanah all together), and the second lists them in order of composition (Rosh Hashanah 1939, followed by Shabbat Teshuvah 1939, and so on). In other words, the editors of the printed version felt that the audience would most likely be asking “what did the Rebbe say when the Torah portion of Noah is read” rather than “what did the Rebbe say in the Fall of 1939, before the wall was built around the ghetto,” a very reasonable assumption for an audience of the faithful.

The broader historical and philosophical layers, the very archaeology of the Rebbe’s thinking, are not at all represented in the bound pages of Aish Kodesh. It is therefore impossible to conduct any serious study of the Holocaust writings of the Piaseczno Rebbe without carefully consulting the manuscript version.

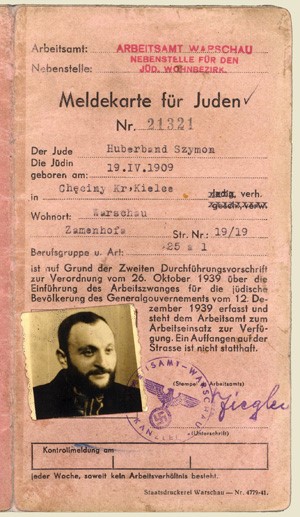

Warsaw Ghetto registration card of Rabbi Shimon Huberband, 1909-1942

Warsaw Ghetto registration card of Rabbi Shimon Huberband, 1909-1942

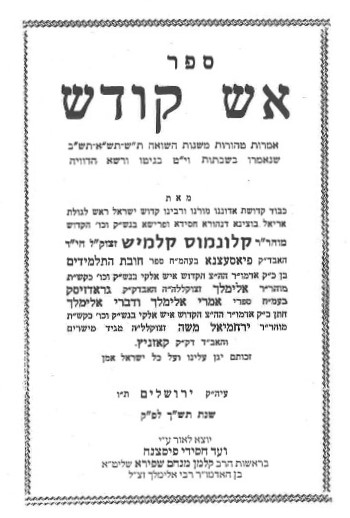

Discovery of the Aish Kodesh

The story behind the Aish Kodesh is almost as amazing as the book itself. On January 3, 1943, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapiro, Rebbe of the Piaseczno Hasidim in Warsaw and Rosh Yeshiva of Da’as Moshe, recorded his last will and testament. His sole possessions of value were his unpublished manuscripts, and he bequeathed them to his brother Yeshayahu Shapiro of Tel-Aviv. With no way to deliver them, the Rebbe entrusted the manuscript to Emanuel Ringelblum, the underground historian of the Warsaw Ghetto who organized the clandestine Oneg Shabbos Archive. Ringelblum placed the Rebbe’s precious manuscripts together with many other documents in a series of tin milk cans and buried them in three sites around Warsaw. Entombed below the streets of the ruined city, the Oneg Shabbos Archive survived its creators: Ringelblum and the Rebbe were martyred, along with well over 300,000 Jews who once lived in the Polish capital. It was not until December 1950 that a Polish construction worker, clearing the rubble of the ruined ghetto, came across the first cache, and turned the milk cans with their holy contents over to the Jewish Historical Institute.

Aish Kodesh contains 86 sermons, most of which were delivered on Saturday afternoons as shalosh seudos droshes stretching from Rosh Hashanah of 1939 to Shabbat Hazon of 1942, the eve of the massive deportations to the Treblinka death camp. Then, the Rebbe apparently lived in hiding in the Ghetto for some months prior to the major uprising of April 1943, making textual emendations to his manuscript. He was deported to a labor camp and was killed in November of that year, possibly in the context of a prisoner uprising. These sermons, which the Rebbe titled “Torah Thoughts from the Years of Wrath, 1939-1942,” were published as Aish Kodesh (Holy Fire).

Aish Kodesh has been studied extensively. It is the subject of many PhD dissertations and several monographs, most notably Dr. Nehemia Polen’s The Holy Fire. Most studies focus on the text’s theological and literary value, and in fact, as a record of public Hasidic sermons document emerging from the Holocaust, it is sui generis. My research, however, concentrates on its historical value. Picking up on a 1980 suggestion made by Ester Yehudit Tidor-Baumel, then a graduate student at Hebrew University, my work takes advantage of the fact that each of the Rebbe’s sermons is dated. By studying the rich memoir literature and documentary record from the period, we can get a very good sense of the events that transpired in the ghetto immediately prior to the Sabbath. Armed with this knowledge, even the most opaque passages in Aish Kodesh take on new meaning, as we begin to hear the Rebbe’s words in a manner that approaches, however distant, the mindset of his audience.

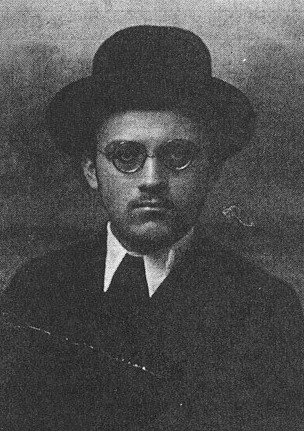

Rabbi Elimelekh Shapiro הי׳׳ד

Rabbi Elimelekh Shapiro הי׳׳ד

Aesopian Language in Aish Kodesh

The historical approach is especially useful given the Rebbe’s predilection for using Aesopian language, meaning, veiling his true intent behind parables and coded language. His basic intent is clear throughout: with his sermons, the Rebbe struggled to bolster the spirits of his beleaguered followers, rousing them to remain steadfast in their attachment to Judaism and Jewish practice despite the increasing horrors of the Nazi onslaught. The weekly shalosh seudos gathering on Saturday afternoons seemed an ideal forum for such a message—clustered around their Rebbe in the gathering dark, the Hasidim hung upon his every word for kernels of strength to carry into the week beyond (I have been privileged to attend shalosh seudos at the Aish Kodesh synagogue in Woodmere, New York, where Rabbi Moshe Weinberger’s congregants faithfully mark the passing of the Sabbath in this manner, singing mournful hasidic melodies in a darkened room, thick with intensity and emotion).

Yet the Sabbath itself forbids open discussion of depressing topics, and as a result the Rebbe’s words are artfully occluded by the shared vocabulary of Midrash. Nowhere does the Rebbe speak about Nazis or Germans; rather he speaks of the biblical nation of Amalek or the Seleucid Greeks. In one telling passage in November 1939, he briefly loses himself and refers to Nazis as “them;” otherwise this pattern of intentional obfuscation is maintained in all the Sabbath sermons and broken only in the notes he appended for later publication.

Consider an example from Aish Kodesh that demonstrates the use of Aesopian language while highlighting the value of the manuscript version over the printed text: Haye Sarah, a brief message delivered on November 4, 1939. The historical context is absolutely essential to understanding this passage. This is only the third entry in Aish Kodesh. The first two (Rosh Hashanah and Shabbat Teshuvah) were probably written before the bombardment of Warsaw began with the onset of the holiday, and in many ways these sermons are broadly similar to those which the Rebbe delivered throughout the 1920s and 30s (published in a separate volume entitled Derekh Ha-Melekh).

On the morning after Yom Kippur 1939, tragedy struck the Rebbe’s home. A mortar fragment flew through a window and grievously wounded the Rebbe’s only son, Elimelekh. The Rebbe, together with his daughter-in-law and sister-in-law, rushed the young man to the overcrowded hospital, seeking emergency treatment. The harried staff admitted him but demanded that the family remain outside—the women stood by the entrance reciting psalms, and the Rebbe rushed off to the home of a doctor who might be able to intervene. While he was away, another round of Luftwaffe bombs rained upon the hospital, killing the Rebbe’s family. His son survived for a few more days, finally succumbing to his wounds on the second day of the holiday of Sukkot.

No entries are recorded in Aish Kodesh for six weeks. Then, on November 4, the Rebbe broke his silence with the following:

It is written in the holy work Ma’or va-Shemesh, at the beginning of Parashat Va-yera, in the name of the the holy rabbi, the man of God, our teacher and master, Menahem Mendel of Rimanov (may the memory of the righteous and holy be for a blessing), regarding the Talmudic passage: “a covenant is made with salt, and a covenant is made with afflictions. Just as salt makes meat palatable, so too afflictions purify [the individual of sin]:” “just as one cannot derive pleasure from meat that has been excessively salted, rather only if it was properly salted, so too afflictions should be meted out only in such measure that they can be tolerated, and with an admixture of mercy.” “Rashi explains that “the death of Sarah was juxtaposed to the binding of Yitzhak because [with the news that her son was being bound and was about to be sacrificed] her soul burst forth from her and she died.” That is to say, Moshe our Teacher, the faithful shepherd, juxtaposed the death of Sarah to the binding of Yitzhak in order to advocate for us, indicating what results from excessive afflictions, Heaven forbid—”her soul burst forth and she died.” Furthermore, if this was the case with the tremendously righteous Sarah, who was as blameless at the age of 100 as a twenty-year-old, and all of her years were equally good, yet despite this she was unable to withstand such horrible afflictions—how much the more so does this apply to us.

The message is challenging on a theological plane, and in many ways characteristic of the electric quality that pervades the Rebbe’s writings. The Rebbe poetically argues that Moses, as original scribe and therefore editor of the Torah, intentionally placed the reference to Sarah’s death immediately after the narrative of the binding of her son Isaac in order to deliver a human message to the Divine: too much suffering can break a person.

On its own, the sermon is incredibly potent, a startling illustration of Menahem Mendel of Rimanov’s hasidic teaching. The historical context, however, renders the passage absolutely terrifying—these are the first words that the Rebbe uttered publicly since the deaths of his son, daughter-in-law, and sister-in-law. One can only imagine the tension in the room as he delivered this sermon: “afflictions should be meted out only in such measure that they can be tolerated, and with an admixture of mercy.” The Rebbe couches his veiled communication—really, a personal communication between the Rebbe and his God—within the biblical and midrashic narrative of Sarah’s death. Openly expressing his anguish and grief would have been inappropriate—the Aesopian rereading of a story well known to his audience placed his personal pain in communal context.

The printed version of the text, however, glosses over an important element in the manuscript version. Immediately prior to the penultimate sentence, the Rebbe inserted a shin-shaped notation, indicating a later marginal annotation to be added in the published version.

We do not know when the Rebbe reviewed his manuscript, but several dated annotations indicate that he did so in late 1942 and early 1943. It is likely that the following passage was inserted at that time:

It is also possible to argue that Sarah the Matriarch, who was so heartbroken with the binding of Yitzhak that her soul burst forth, did so for the benefit of the Jewish people, to demonstrate to God how it is impossible for the Jewish people to tolerate excessive afflictions. Even for one who remains alive after such afflictions by the grace of God, nevertheless some of his strength—his mind and spirit are broken and destroyed. Is there a difference between partial and total death?

A problem is resolved by the verse the years of the life of Sarah. It seems that Sarah may have sinned by forsaking the remaining years of her life, had she not chosen to be so heartbroken over the binding of Yitzhak. Since, however, she forsook them for the benefit of the Jewish people, the verse subtly indicates the years of the life of Sarah. That is to say, that even those years beyond her 127 would have been equally good—even forsaking them did not constitute a sin on her part.

On the one hand, the Rebbe pushes the theologically challenging material still further, arguing that Moses was not the only biblical figure to consciously protest excessive suffering—Sarah, by virtue of allowing herself to die with the shock of the news of Isaac’s experience, was also issuing the ultimate statement of dissent, and that “she did this for the benefit of the Jewish people.” Perhaps this idea was discussed at the shalosh seudos or even later between the Rebbe and the Hasidim (the entries in Aish Kodesh are taken from the notes the Rebbe jotted down after the conclusion of the Sabbath), and the Rebbe wished to include it within the body of the sermon itself. On the other hand, he clearly wishes to absolve Sarah of any culpability for her choice, allowing herself to be “so heartbroken,” perhaps in recognition of those in the Ghetto who could no longer bear a level of suffering that is beyond our comprehension. The sermon concludes with a prayer: “Thus may God have mercy on us and all Israel and speedily redeem us, spiritually and physically, with revealed acts of lovingkindness.”

Conclusion

Aish Kodesh is a work of phenomenal spiritual heroism, a testament to human resilience and even angelic holiness radiating from the very depths of human depravity. It will undoubtedly serve as a source of guidance and inspiration for students of Judaism in particular and religion in general.

Dr. Greenberg’s gift of the manuscript set my research back many years. At the same time, however, it deepened and enriched my understanding of the Aish Kodesh as a holy work, and appreciation for the grandeur of its author. The printed text captured the final form of the Rebbe’s thought, formulating his ideas in a manner that conveyed a consistent message of courage and hope. Perhaps that’s also the way the sermons sounded to his audiences in the Ghetto.

Yet, working with the manuscript I was granted a rare and rich glimpse into his turbulent internal life, struggling to find the correct Aesopian phrases that would capture the imagination of his Hasidim and lead them across the narrow bridges that linked their quotidian suffering to the world of the Patriarchs and the Matriarchs. By drawing these parallels, the Rebbe offered a vision of the cosmos that gave meaning to the tremendum of the Holocaust, translating their incomprehensible experience into the language of the Torah, week after week. Aish Kodesh is truly a phenomenal work. Only with careful exploration of the immediate historical context, however, combined with the literary archaeology of the manuscript rather than the printed text, will its true power be revealed.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.