Mark Glass

I.

A long time ago in a galaxy far far away. …

Growing up, that’s how the gabba’im of my youth minyan would determine if a minyan was present. Aware that there was not only a prohibition against counting the number of Jews in a room but also a well-known workaround – to use the ten-word verse from Psalms beginning hoshi‘a et ammekha (Ps. 28:9) in lieu of the numbers “one, two, three, etc.” – the gabba’im perfectly blended piety with sacrilege in using an alternative ten-word sentence more in keeping with their community: the opening to every Star Wars movie.

But for all the obvious problems with using pop-culture to count a minyan, there is a greater issue still. Because while R. Shlomo Ganzfried codifies the use of Ps. 28:9 in his Kitzur Shulhan Arukh (15:3), the Star Wars method seems to suffer from a fatal misunderstanding of the mathematics behind the prohibition on counting that renders it (on the surface) an unhelpful solution.

It is only by unpacking the prohibition on counting Jews alongside an understanding of its mathematical underpinnings that the merits and pitfalls of various halakhic solutions can be appreciated—including R. Ganzfried’s, which, when reevaluated, can be seen as far more mathematically workable than how it is often understood.

II.

It is undeniable that Judaism prohibits counting Jews. But it is tricky to pin down the exact reason and rationale. Not only do a variety of Talmudic explanations clash, but many different scriptural sources are suggested as the reason for definitively prohibiting counting—a challenge further exacerbated by the fact that the prohibition is never counted among the 613 Biblical commandments in the various sources that list them.

And if that weren’t enough, neither the Shulhan Arukh nor Rema codify the prohibition. Nonetheless, not only does Rambam explicitly do so (Hilkhot Temidim u-Musafim 4:4) but a who’s who of Aharonim, in addition to R. Ganzfried, emphatically declare counting Jews to be prohibited: R. Avraham Gombiner (Magen Avraham 156:2), R. Hezekiah da Silva (Peri Hadash 55:1), R. Hayyim Palaggi (Kaf Ha-Hayyim 13:10), and R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi (Shulhan Arukh Ha-Rav 156:15).

But the mere existence of the prohibition’s codification does not weaken the major challenge of discovering its scriptural source. Take what might seem the most obvious Biblical source prohibiting counting Jews, in which God explicitly instructs Moses to conduct a census via an indirect method: each person must give exactly one half-shekel, and those half-shekels are counted to calculate the population “so that no plague may come upon them as they are counted” (Exodus 30:11–16).

At first glance, these verses not only perfectly characterize the prohibition against counting Jews but also offer a workaround: count something else. And this is, indeed, the scriptural source cited by Hazal when discussing King David’s calamitous census (II Sam. 24:1–15). David’s failure to heed the command to count Jews via a half-shekel (or any other medium) led to a plague descending upon Israel—the very consequence explicitly stated by God to Moses. To boot, Hazal stress that “even schoolchildren” know it is forbidden to count Jews from the verses in Exodus 30 (Berakhot 62b).

Yet, for all the obvious appeal of Exodus 30 and the fact that even children know it as the prohibition’s source, it is conspicuously absent from a different Talmudic discussion of the prohibition—one more grounded in practical halakhah than the aggadic discussion concerning David’s failed census.

The Mishnah describes the way in which the kohanim would compete for the honor of removing the ashes from the altar each morning: they would race up the altar’s ramp and whoever won the race would remove the ashes (Yoma 2:1). But, as the Mishnah proceeds to explain, in the event of a tie, all the kohanim would be entered into a lottery, instead, to determine the winner. Standing in formation, the priestly officer in charge would pick a random number and instruct the Kohanim to extend a finger. He would then count the fingers until he arrived at the winning number.

Commenting upon this mishnah, the gemara asks why the kohanim are told to extend their fingers. Why not simply count the kohanim themselves? The gemara answers by quoting R. Yitzhak’s ruling that “it is forbidden to count Jews even for the purpose of a mitzvah” (Yoma 22b).

And while a reader might expect the gemara here to then cite as prooftext Exodus 30—the source even schoolchildren know prohibits counting Jews—a different verse is offered, which describes David’s predecessor Saul conducting a military census:

Saul mustered them in Bezek, and the Israelites numbered 300,000; the men of Judah 30,000 (I Sam. 11:8).

And though this verse offers no obvious indication that Saul avoided the prohibition against counting Jews (indeed, it could indicate the opposite), R. Yitzhak suggests a radical reinterpretation of the verse. Saul didn’t count his troops at the location called “Bezek.” Rather, he counted his troops via “bezek,” “shards of pottery.” Each soldier brought (or took) a pottery shard and Saul counted each and every one to determine his army’s size.

And while R. Ashi immediately objects to this scriptural source, he does not offer Exodus 30 as an alternative, because his gripe is not with R. Yitzhak’s decision to creatively interpret Saul’s actions here, but something far simpler. “Bezek,” he argues, is too obviously the name of a location, given it appears in Judges 1:5. Instead, R. Ashi suggests a near-identical verse describing another military census of Saul:

Saul mustered the troops and enrolled them at Telaim: 200,000 men on foot and 10,000 men of Judah (I Sam. 15:4).

Here, R. Ashi suggests the same logic. It’s not that Saul counted his troops at the location called “Telaim.” Instead, he counted his troops via “tela’im,” “sheep.” Each soldier brought (or took) a sheep, and Saul counted the sheep to determine his army’s size.

But regardless of which source from I Samuel is the source of the prohibition here, that neither verse explicitly addresses counting—with Hazal relying on, instead, an incredibly creative rereading of the verses—is a confusing choice, made all the more so by the gemara’s quoting of R. Elazar, who invokes a different verse altogether to prove that it is prohibited to count Jews. R. Elazar’s suggestion could not be further removed from a description of the correct approach to conduct a census. Instead, he relies on Hosea’s declaration that the Jewish people are considered like the sand of the sea, “which cannot be measured” (Hos. 2:1).

All of which seems to point more to Hazal’s aversion to invoking Exodus 30 than to their belief that there are other verses from which the prohibition emerges, leading to many attempts to explain Hazal’s motivation. R. Shmuel Eidels, for example, suggests that the wider context of Exodus 30 makes clear that it’s not really about the prohibition against counting Jews. Instead, God insisted that the people each bring a half-shekel as penance for the sin of the Golden Calf (Maharsha to Yoma 22b, s.v. “asur limnot et Yisra’el”).

Alternatively, as R. Eliezer Waldenberg argues, there are simpler and more technical reasons as to why Hazal did not root the prohibition in Exodus 30. Given R. Yitzhak’s insistence that one cannot count “even for a mitzvah,” Exodus 30 is an insufficient example because there is no mitzvah; God never commands Moses to conduct a census at this point (Tzitz Eliezer 7:3).

The only thing that clearly emerges from the above is the lack of clarity regarding the source of the prohibition against counting Jews. Yet one single Talmudic story draws attention to what might be a uniting theme for the debate. When King Agrippa wished to conduct a census of the people, he instructed the High Priest to count his people using the paschal offerings (Pesahim 64b).

In addition to the shekels, shards, and sheep of the scriptural sources, this gemara states that the High Priest counted the kidneys of each sacrifice. Combined with the Priestly officer’s counting of fingers in the Mishnah, one single thread connects all these otherwise disparate and disagreeing sources: they all recognize that an intermediary must be used to count Jews.

And indeed, Targum Yonatan reinforces this connective thread by interpreting Saul’s census at Telaim through the prism of King Agrippa: “And Saul gathered the people and counted them by their paschal lambs” (Targum Yonatan, I Sam. 15:4).

III.

For many Rishonim and Aharonim who discuss the prohibition to count Jews, this permissibility of using an intermediary (perhaps only under certain circumstances) becomes the sole source of agreement even as all the other details are debated.

The medieval Italian Tosafist R. Isaiah di Trani, for example, stresses that when one is counting Jews for a mitzvah it must be done via a davar aher, “something else” (Tosafot Rid to Yoma 22b) – a point also noted by Rabbis David Kimhi (Radak to I Sam. 15:4, s.v. “ba-tela’im”) and Hayyim ibn Attar (Or Ha-Hayyim to Ex. 30:12 s.v. “od”). Nachmanides, too – among his many analyses of the prohibition – suggests the centrality of an additional medium in avoiding the prohibition (Ramban to Ex. 30:12).

Similarly, R. Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin (“Netziv”)—in discussing the census conducted at the beginning of the Book of Numbers—cites approvingly an idea originating with R. Isaac Luria, that Moses did not count the people directly but rather via slips of paper (Ha’amek Davar to Num. 1:42).[1] And in addressing the controversy of counting Jews when conducting a formal census, Rabbis Yehiel Yaakov Weinberg (Seridei Esh II §48), Ben-Tzion Uzziel (Mishpetei Uzziel, Hoshen Mishpat Kellalim 2), and Menahem Mendel Kasher (Torah Sheleimah XXI p. 168) all argue that the names written on a form constitute a legitimate alternative object to count.

But perhaps the most forceful recognition that the permissibility of counting Jews hinges on the use of an intermediary is found in the writings of R. Avraham Bornsztain, who insists that the reason the Priestly officer was permitted to count the kohanim’s fingers was that “the finger is not an intrinsic part of the person” (Avnei Neizer to Yoreh Dei’ah 450:10), an admittedly confusing comment clarified by another responsum: “one who counts fingers is not considered to be counting the Jew themselves” (ibid. 452:5). In other words, the finger is considered alternative enough of a medium to be counted. In a similar vein, R. Yisrael of Shklov argues that a person’s finger is sufficiently divorced from their head and thus may be counted (quoted in Hatam Sofer, Kovetz She’eilot u-Teshuvot §8).

Admittedly, the above does not imply total rabbinic consensus. Hatam Sofer’s reason for quoting R. Yisrael of Shklov is to disagree with him, and though R. Moshe Feinstein does not explicitly name Avnei Neizer, he disagrees with his thesis (Iggerot Moshe, Yoreh Dei’ah III §117:2). But even in this latter case, as R. Asher Weiss argues, R. Feinstein’s issue might be narrowly restricted to opposing the argument that some body parts are sufficiently divorced from a person; he might permit counting an article of clothing a person is wearing (Minhat Asher, Bamidbar §1:6).

What thus emerges from all of this is the existence of a formidable school of thought—spanning Hazal through to the modern era—arguing for the fundamental distinction between counting Jews directly and counting them via an additional object. And while it may appear to be nothing more than a workaround, a fundamental mathematical principle validates the distinction.

IV.

In her delightful book, How to Bake π, Eugenia Chang uses a familiar scene to illustrate the profound mathematics at the heart of counting.[2]

Picture the proud parents of a toddler declaring their child’s ability to count to ten, which the child then proceeds to do upon command. But, as Chang notes, what is more likely is that all the toddler has learned are the words to a simple ten-word poem, “one, two, three…”. If you place seven apples in front of the child and ask them to count them, they’ll probably just recite the full ten-word poem while pointing at the apples.

This example uncovers the difference between the appearance of counting and the mathematics of counting—a profound mathematical operation that we learn so early that we never have to think through just how complex it is.

The technical term for counting is “abstraction,” the ability to ignore the specific and distracting and notice, instead, commonalities. As Edward Dolnick writes, quoting Alfred North Whitehead:

It was a notable advance in the history of thought when someone hit on the insight that two rocks and two days and two sticks all shared the same abstract property of “twoness.” For countless generations no one had seen it.[3]

And so, whether we’re counting ten men or ten apples, the process is the same. It begins by ignoring the fact that they are men or apples in favor of representing them abstractly as a number that can then be counted.

But what must be stressed here is that there is no inherent magic to the word “two,” for example, other than what it conveys, which we would term “twoness”—but, again, these words need not be used. The concept of two and twoness would be just as easily comprehended if we used the word deux or shtayim or “blurgh” or “et.” What matters is not the word used but the concept it characterizes.

The difference between the child who can count and the child who cannot is never their use of a ten-word “poem,” because every English speaker uses the same poem. The difference lies in the child’s ability to abstract objects to the words of the poem. In a sense, then, the words we use for numbers are simply constructs that convey deeper meanings.

This provides more precise mathematical language to help reframe the permissible approach to counting Jews via an intermediary. What is prohibited is the direct abstraction of Jews. When directly counting people, their personhood is removed—they are abstracted—simply represented by a number.

Indeed, the one scriptural source suggested above that bears no relevance to conducting a census— Hosea’s declaration that the Jewish people “cannot be counted”—might highlight the significance of this understanding. If Hosea’s declaration is seen as a metaphorical statement about how dear the Jewish people are to God rather than a factual statement about the Jewish people’s numerosity, it is a prophetic statement about the problem of reducing Jews into abstractions.[4]

An indirect count, however, contains a subtle but key mathematical difference. Because here, while abstraction still takes place, no Jews are abstracted. When they represent themselves as shekels, shards, sheep, or whatnot, they are never directly abstracted.

V.

It should be noted that this theory defies one of the most emphatic explanations for the prohibition that finds its origins in a comment of Nachmanides (different to the one mentioned earlier) that the prohibition is only to count the entire Jewish people rather than a subset thereof (Ramban to Num. 1:3, s.v. “tifkedu otam”).

The reason for Nachmanides’ distinction, according to R. Moshe Sofer,[5] is that an incomplete count is always imprecise (Hatam Sofer, Kovetz She’eilot u-Teshuvot §8). As Hatam Sofer explains, there is no certainty here. Counting a smaller group is permitted because the counter merely requires a rough assessment of how many people are assembled.

This perspective has merit; all the sources discussed by Hazal describe counts where it was easy for error to creep in. It is not hard to imagine some of Saul’s less-enthusiastic soldiers failing to pick up a pottery shard or sheep—or a few of his more gung-ho soldiers picking up extra out of sheer excitement.[6]

Similarly, the Talmudic story of King Agrippa recognizes the likelihood of error in the High Priest’s calculation. Not every Jew was able to bring the paschal sacrifice, some being either impure or too far away; the census was definitionally inaccurate.

And the same is true regarding the lottery conducted by the Priestly officer. Because not only does the mishnah explicitly state that a priest could extend either one or two fingers, but Rambam assumes that some Kohanim would sneakily extend more than two (Commentary to Mishnah, Yoma 2:1; Hilkhot Temidim u-Musafim 4:3). And many of the other sources mentioned can be reinterpreted in this light.

Yet for all the merits of Hatam Sofer’s theory of imprecision, it makes it practically impossible to follow. Because one of the most central needs to count Jews without violating the prohibition is to determine if a minyan is in the room,[7] and here there can be no room for error. One cannot roughly count the number of Jewish men in the room and be unsure whether there are nine or ten. The count must be precise.

Hence the need for a method of precisely counting Jews under certain circumstances using indirect abstraction. But here the fatal flaw in using Ps. 28:9 emerges. Because when the gabbaim of my youth minyan used “A long time ago in a galaxy far far away” to determine if a minyan was present, their actions were mathematically equivalent to using “one, two, three, etc.” They still abstracted each and every male in the room to a series of ten words—only this time they used the opening of Star Wars.

And the same is obviously true of using the ten words of Ps. 28:9. Because the specific words we use do not matter: the problem is the abstraction. “One, two, three,” “ahat, shtayim, shalosh,” “un, deux, trois,” and “hoshi‘a et amekha” are all functionally equivalent. The mathematics never changes, only the words. People are still directly abstracted as the count is still conducted—thus violating the prohibition of abstracting Jews.

VI.

But the use of Ps. 28:9 to count Jews without avoiding the prohibition may be the product of a misunderstanding. Because nowhere does R. Ganzfried spell out how to use Ps. 28:9 to avoid the prohibition. All he states, after codifying the prohibition, is that “it is customary to count them via reciting the verse ‘hoshi‘a et amekha,’ which contains ten words.”

And while the obvious understanding is to use these ten words in lieu of the numbers one to ten, there is another possible interpretation.[8]

Two different early medieval codes, Sefer ha-Orah (§56)—attributed to Rashi—and R.Yehuda ben Barzillai’s Sefer ha-Itim (§174) both describe in detail a workaround to the prohibition of counting Jews that also relies on a ten-word verse from Psalms, va’ani be-rov hasdekha, “But I, through Your abundant love, enter Your house; I bow down in awe at Your holy temple” (Ps. 5:8).

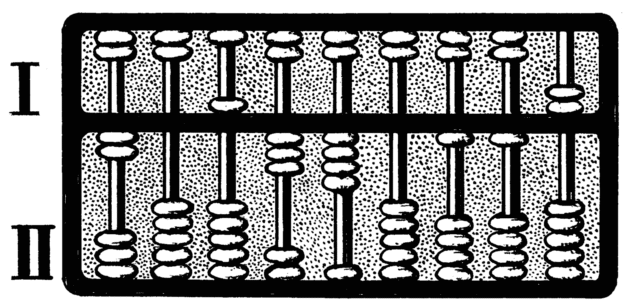

And while it should be noted that, thematically, this verse fits far better with the need to determine a minyan—given it references the entering of God’s house—the way it was used was not as a substitute for numbers. Rather, to determine if a minyan was present, the men assembled would go around the room with each one saying a word of the verse until the entire verse could be completed.

And while this doesn’t appear too dissimilar to the use of Ps. 28:9, there is a fundamental difference. By calling out one word in a verse nothing much has happened mathematically—yet now, instead of one person directly abstracting the Jews in the room to a ten-word verse, it is the words themselves that are abstracted. Much in the same way that the kohanim would extend fingers to be counted, here the people in the room “extend” a word of the verse. And it is thus not unreasonable to assume that R. Ganzfried’s suggestion is the same. The use of Ps. 28:9 is not in lieu of numbers but as an alternative process.

*

Few prohibitions are as effortless to violate as the one against counting Jews. Yet its mathematical underpinnings reveal a better way to understand not only it but how some of the workarounds are fundamentally different.

[1] The actual process described by Netziv is a tad convoluted, but the concept is identical: the people were counted via an additional medium.

[2] Eugenia Chang, How to Bake π: An Edible Exploration of the Mathematics of Mathematics (Basic Books: New York, NY) 2015, 15–43.

[3] Edward Dolnick, The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society & the Birth of the Modern World (HarperCollins Publishers, NY; 2011) 195

[4] This also fits with what is otherwise a curious and hard to explain position of Rashi, who offers his own scriptural sources for the prohibition against counting Jews – Gen. 13:11 and 32:13. But both verses recognize the preciousness of the Jewish people (Rashi to I Chron. 27:24, s.v. “va-yhi be-zot ketzef al Yisrael”; Rashi to I Sam. 15:4, s.v. “va-yifkedeim be-tela’im”).

[5] While I must express my general appreciation to Chesky Kopel for being such a wonderful editor, specific credit must go to his realization that Rabbi Sofer is the perfect name for a rabbi who addresses the issue of counting.

[6] I should stress that Hatam Sofer develops his own theory regarding the purpose of the sheep in Saul’s census.

[7] A point explicitly noted by both Peri Hadash and Kaf Ha-Hayyim.

[8] One perspective that I’ve not considered in this article is the belief that the use of Ps. 28:9 serves as a protective ward against any of the ill-effects of counting Jews. While this is an opinion worthy of further study, I am not reckoning with it in the body of the article because it not only assumes that the major concern is plague – an Exodus 30-centric perspective – but seems to also concede that the prohibition is violated in some sense but there nonetheless exists a mystical, rather than a mathematical, method of abrogating the issue. Indeed, Ps. 28:9, which asks God to save His people, becomes a particularly poignant request if the counter knows they are violating a prohibition with disastrous consequences.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.