Batya Hefter

This piece is dedicated in memory of Sergeant Efraim Jackman a”h, a holy soldier who fell fighting in Gaza on Tuesday, Dec. 26th.

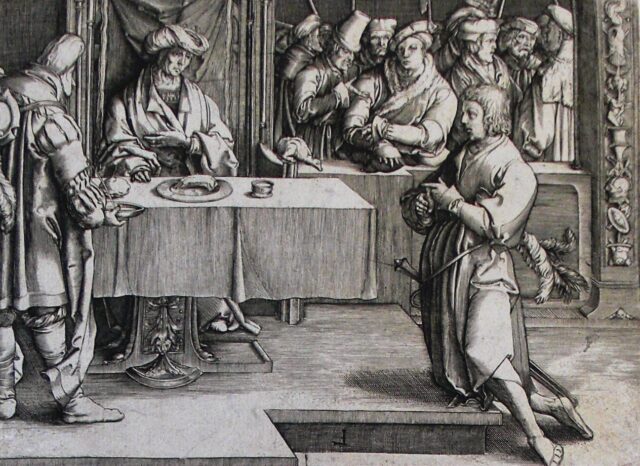

R. Mordechai Yosef Leiner, (b. 1800), founder of the Ishbitz-Radzyn dynasty, offers an innovative reading of the famous story of the baker and the steward at the end of the book of Genesis. He suggests that the dreams told to Joseph in great detail by these two minor characters are meant to be understood as God’s way of communicating with Joseph, imparting to him vital information about himself and his flaws, and offering him guidance on his path towards spiritual refinement, known in Ishbitz-Radzyn terminology as beirur. He taught that God, like every king, has two ministers: one is like the baker who shares Joseph’s prison cell, and the other, like the wine-steward. If the baker represents Joseph – cautious, watchful, always following the rules, the wine-steward – less exacting, who flows with the rhythm of life, represents Judah.[1]

Judah, unlike Joseph, is fully engaged in the moment, spontaneous, intuitive, and bold. While Joseph approaches life primarily through reason and devotion to pre-established principles, Judah approaches life through intuition. Judah’s dominant trait is an understanding heart, binah ba-lev. Joseph analyzes, protects, and plans. Judah, in contrast, encounters life events as they present themselves. With no visible map in hand other than his innate sense that God resides even in the darkest of places, he sins, falls, and then rises to unexpected heights. As we shall see, according to the worldview of the Ishbitz-Radzyn Masters, life is not neat and linear; religious devotion comes in many forms.

Judah, as he is portrayed in this tradition, embodies the spiritual mindset that relies on the heart that aims directly towards God for guidance.

“The vital life source of Judah,” writes R. Mordechai Yosef, “is to continuously look towards the Holy One, Blessed be He, in every circumstance.”[2]

In Ishbitz-Radzyn thought, the religious ideal is to align one’s actions with God’s will, to obtain a discerning heart. Judah’s binah ba-lev matures over the course of his long, difficult life.

Judah’s Beginnings: Selling Joseph – Faltering Leadership

In the first chapters of the lengthy saga of Joseph and his brothers, two figures are prominent: Reuben, Jacob’s firstborn son, and Judah, his fourth. Exhibiting the seeds of contrasting leadership qualities, each one tries to dissuade the brothers from their murderous plot against Joseph. But it is Judah who prevails.

Reuben, with the best intentions, invokes impersonal, legal principles: Why should you dirty your hands? he implies, “Cast him into this pit…and lay no hand upon him” (Genesis 37:24); that way, he will die of his own accord, and you won’t be guilty of murder.

Judah, however, appeals to their sense of brotherhood. Four times in the space of two verses the Torah uses the word “brother,” specifically mentioning that “his [Judah’s] brothers listen to him.” He commands their attention as he appeals directly to their emotions: “How can we kill our brother…for he is our brother, our flesh and blood?” (Genesis 37:26-27). Having their ear, we might have expected Judah to rescue Joseph entirely and save his father years of agonizing misery.

But Judah, at this point in the story, has not yet reached his full moral potential, and instead offers a compromise. Suggesting that they sell him, he saves Joseph’s life, but does not go as far as to return him safely to his father. True, he shows the strength to convince them of a different path, yet he fails to uphold clear ethical principles as a genuine leader should. Judah ultimately abandons Joseph, resulting in long years of suffering for all involved.

In this traumatic opening scene, Judah is a figure of ambiguous, if not negative, moral fiber. The next stages of his life story chart a journey downward until he hits bottom. The first words of the following section of the Torah itself indicate this decline.

Judah Descends

And it came to pass that Judah went down from his brothers. (Genesis 38:1)

On the phrase “went down,” Rashi teaches:

His brothers degraded him from his high position. When they saw their father’s grief, they said, “You told us to sell him; if you had told us to send him back to his father, we would also have obeyed you.”[3]

Judah was a natural leader whom others were willing to follow, but he squandered his influence and paid the price for it, losing his brothers’ respect and, as we will see, his own sense of self-worth.

Blamed by his brothers for his father’s inconsolable misery, Judah leaves his home and his family and remains displaced, exiled for nearly a lifetime. But the word vayeired, “and he went down”’ foreshadows multiple phases, for Judah’s descent has only begun.

Almost immediately, the Torah relates, he marries and has children. Knowing full well that his father Jacob is mourning over his loss of Joseph, R. Mordechai Yosef wonders, “Why did Judah get married at a time like this? How could he do such a thing when his family was mourning?!” R. Mordechai Yosef suggests that these actions are Judah’s own response to his failed leadership. Weaving together the details of Judah’s life as depicted in the Torah, R. Mordechai Yosef describes:

When Judah saw that “Jacob refused to be comforted,” and since it had fallen upon him to bring [Joseph’s bloody] coat to his father, he fell into deep despair, and thought there was no more hope for him. Therefore, he went to marry a woman, as he said to himself, “Maybe I will have good sons and continuity and salvation will come from them.”[4]

Rabbi Mordechai Yosef explains that at this moment Judah believed that his own life was hopeless. Because of his disgraceful behavior, he thought there was no chance for forgiveness, no way to heal and repair his soul. And so, in a desperate attempt to redeem himself, Judah wishes to bear children, placing all of his hopes on his unborn sons. Perhaps, he thinks to himself, they, unlike him, will be good, upright people. [5]

His first two sons “do evil in the eyes of the Lord” and, in quick succession, are slain by God. Judah’s wished-for future, that his sons might restore his worth, fades away. He compromised, sold his brother Joseph, deceived his father, and hoped in vain that his sons would transcend his flaws, but to no avail.

From Compromise to Deception

After his two sons die, Judah tells his daughter in law, Tamar, to wait for his third son, Shelah, to come of age so they can marry and have a child who will “carry on the name” of his dead brother. But the Torah implies that Judah has no intention to give his third son to Tamar, as he is convinced that she is an ishah katlanit,[6] a black widow, the cause of his sons’ deaths. Instead, he misleads her, sending her home to wait in vain for this son to grow up, condemning her to the fate of a perpetual widow.

But God has other plans.

R. Mordechai Yosef asserts that God communicates with Judah, not in dreams as He did with Joseph,[7] but through the events in his life. God’s message regards the value of Judah’s own life and the work he must do on himself. R. Mordechai Yosef portrays God as challenging Judah:

“If, heaven forbid, you truly believe there is no hope for you, and that you have no life at your root, then even if you have a hundred children, they will never have any more ‘life’ (true vitality) than you.”[8]

In other words, God says to him: “You, Judah, like all people, are a channel through whom God provides life.[9] But as of now, that channel is blocked. Until you repair yourself, no number of children you have will ever live or bring about relief.”[10]

Judah must learn not to despair; he must overcome his feeling of futility, for there is always the possibility of repentance. He must have faith that things can change; that he can change. Only then will he be able to contribute anything everlasting to this world.

Judah will learn to interpret the events in his life. But for now, desperate to save his future, he cannot see the present clearly, looking everywhere except to himself. As in Greek tragedy, where the hero, anxiously seeking to avoid his fate, ends up meeting it head on, so Judah encounters his fate in the most unlikely of circumstances. Seeking comfort after the death of his wife in the arms of a woman he is led to believe is a harlot, Judah unknowingly impregnates his own daughter-in-law.

Oblivious to his sin, and to the depths to which he has sunk, Judah now reaches a turning point in his life.

The First Stage of Beirur: The Moment of Reckoning

Tamar’s pregnancy is soon discovered. The assumption is made that she had illicit relations with a man out of wedlock, and the death sentence is promptly pronounced by none other than Judah himself. Rather than produce the evidence, publicly and clearly proving Judah’s involvement, Tamar chooses to wait in silence until the last moment and confront her father-in-law with the objects he had pledged in place of payment.

Even as she confronts him, she does so subtly, never accusing him outright:

She said, “If you would, hakeir na, recognize [these objects]…” (Genesis 38:25)

Will Judah deny the truth, avoid public humiliation, and send Tamar to her death? Or will he own up to his actions, save Tamar, redeem himself, and become the leader he is meant to be? He could act as if those items which he had given as collateral have nothing to do with him, easily contriving elaborate excuses and explanations for his actions. If so, what began as his tendency towards compromise would now degenerate into total corruption.

Judah’s life hinges on his response to this utterly unforeseen moment.

Unlike the moment Judah sold Joseph into slavery, this time he knows there is no room for compromise. As he beholds the objects in his hand, negligence gives way to conscience, deceit to integrity.

His response is immediate, unfaltering, and direct:[11]

“She is more righteous than I am!” (Genesis 38:25-26)

By publicly admitting his guilt, Judah not only saves Tamar’s life, but restores her innocence and dignity. Undaunted by repercussions, he validates her; she is righteous and he is the sinner. Humbling himself before this truth, Judah admits that, by withholding his son Shelah, he had deceived her.[12]

Tamar’s words hakeir na, “recognize please,” echo the very words that Judah himself uttered when he deceived Jacob. Bearing Joseph’s bloody coat in his hands, Judah held it before his father and said, “hakeir na, “recognize please,” whether it be your son’s coat or not” (Genesis 37:32-33).

Her words, familiar and painful, pierced Judah’s heart, stripping him of layers of protective armour that hid decades of his guilt and shame. Vulnerable and exposed, he now stands receptive, ready to take responsibility not just for his negligence of Tamar but for his repressed past, his maltreatment of Joseph and his father.

Transformed, with a clear conscience and an honest heart, he begins to re-evaluate his life.

It is at this moment that Judah embodies two opposing qualities: paradoxically, his greatness, dormant until now, is specifically his humility, his vulnerability. Now, he rises to show himself to be the worthy progenitor of the kings of the Jewish Nation. The union between Judah and Tamar results in the birth of twins, one of whom will become the forefather of King David.

Deeper Meanings of Kingship and Humility

The Ishbitz-Radzyn traditions contemplate this essential paradox: malkhut, kingship, which we naturally associate with initiative, leadership, nobility, and authority, requires the very opposite traits of utter receptivity and humility. The quality of malkhut, according to the mystical tradition, is conceived of as a vessel which both receives and reflects divine abundance. For that reason, malkhut is compared to the moon. Having no light of its own, the moon reflects and reveals the bright light of the sun.[13]

Similarly, the role of the mortal king is to reflect the exclusive values of the Divine King and not those fashioned by his own, limited mind. This can be done by emptying himself of his own self-interested agenda, so that he may reflect something “other,” something transcendent and holy beyond himself. As the Ishbitz-Radzyn masters teach: “The tribe of Judah is like the moon which has nothing of its own. All of its light is only from the sun which shines upon it and gives it light.”[14] Just as the moon, which has no light of its own, reflects the light of the sun, so too Judah’s heart, empty of his own interest, reflects the will of God.

The hasidic masters note that this quality is hinted at in Judah’s name.[15] The Hebrew letters of YeHUdaH, in that order, imply that Judah embodies divinity [Y-H-V-H] and that he is aligned with God’s will. The extra letter dalet, which appears in the middle of Judah’s name, teaches us about his unique capacity: it comes from the root dal, meaning impoverished, or lacking, empty. Judah epitomizes humility; he is able to rid himself of self-interest as he holds the needs of another. He becomes a vessel to reflect God’s will, which in this instance is mediated through his encounter with Tamar.[16]

Judah’s submission before Tamar extends beyond moral accountability. The Sages of the Talmud hint that Judah’s relinquishment of all control is transformed into a spiritual capacity. “When [Judah] confessed and said, ‘She is more righteous mimeni – than I,’ a heavenly voice came forth and said ‘mimeni – from Me, God, and by My agency have these things happened.’”[17] By tuning into this innate receptive faculty, Judah finds that he has become a vessel of God’s will.

In the Ishbitz reading, this is more than a nuanced psychological ability of ethical refinement: Judah’s moral path also shows the way to encounter the infinite God.

The challenge for Judah as he moves forward will be to choose, consciously and proactively, to discern the will of God.

Cultivating an Understanding Heart

Judah, through his experience with Tamar, learned to react to events with a receptive, fully engaged heart.

In hasidic thought, binah ba-lev, or understanding, means attempting to ascertain the divine will at each turn of events. To be so open and adaptable requires subtle attunement to every circumstance as it arises, and the humility and flexibility to react appropriately and authentically in each instance.

Whereas Joseph’s way is rational and measured, following a set plan to which he strictly adheres, Judah’s way is intuitive; his attuned, sensitive temperament takes him on a fluid and more spontaneous path.

In R. Mordechai Yosef’s words:

The vital life source of Judah is to always look towards the Holy One, Blessed be He, in every circumstance, and not to act by rote.

Such spontaneity means constantly renewed receptivity:

Even if today there is a circumstance similar to yesterday, he still would not want to rely on himself [on his decision from yesterday]; rather the Holy One, Blessed be He, will enlighten him anew as to His will.

For R. Ya’akov Leiner, (b. 1818), the son and heir of R. Mordechai Yosef, Judah is the paradigmatic example of binah ba-lev, seeking each day to attune his heart, never relying on what he did yesterday, for each day we are not quite the same as we were the day before, and each moment brings different challenges.

But a person’s heart, as we know, is a tricky, subtle organ. As the seat of desire, it can feast on self-interest and self-deception, justifying unreflective and even corrupt behavior. The Torah warns, “do not follow your heart” (Numbers 15:39). And yet, it is the heart, that very seat of desire, properly directed, that yearns to intuit God’s will, to be illuminated by the Source of all life.[18] What ballast may we give the capricious heart to intuit God’s will?

Michael Fishbane, in his book Fragile Finitude, describes how a spiritual seeker might “find the right balance,” in order to bring herself to that highest level of receptivity. He suggests repeatedly asking ourselves,

“Am I open to reconsideration of the evidence, or have I blocked proper receptivity because of self-interest?”… The ideal is to cultivate a heart of wisdom… Turning inward, the seeker wants a lev nakhon, a “heart rightly attuned” to life and its challenges.[19]

Judah is able to rid himself of all self-interest and candidly look at the events of his life. At this transformative moment, his “rightly attuned” heart opens. He wins an understanding heart – binah ba-lev.

This is surely the first step in his process of beirur. But other than humiliation for the incident involving Tamar, Judah suffers no repercussions. It will be an entirely different matter to choose to take responsibility in the future, to take a step into the unknown when the personal stakes are high.

To enter the unknown with confidence, Judah, as we saw, must strip himself down to nothing, remove all self-interest, and pray that his efforts to make space will allow him to be a recipient of God’s will. This humility will unfold and expand with the progression of the narrative.

Second Stage of Beirur: Judah’s Pledge

Meanwhile, in Egypt, Joseph has set in action an elaborate plan to fulfil his dreams and bring his brothers before him. As the plan unfolds, the brothers, who had gone down to Egypt to bring back food during the famine, are accused by Joseph of being foreign spies. To save their family from starvation, they must convince Jacob to send Benjamin, his beloved, youngest son, with them to Egypt to be presented before the viceroy. Jacob, who is still mourning his loss of Joseph, is reluctant to part with Benjamin. Once again, it is the same two brothers, Reuben and Judah, who step forward, each one asserting himself as the figure of authority that Jacob can rely on to safeguard Benjamin.

Reuben’s good intentions again miss the mark. Trying to guarantee Benjamin’s safe return, he rashly declares, “Slay my two sons if I bring him not to you!” (Genesis 42:37). As in the scene with Joseph at the pit, Reuben’s heart is in the right place; he feels stirred to lead, but his efforts are misguided. Needless to say, Jacob does not feel assured.[20]

At this point, Judah, intuiting just what is required at this moment and filled with a vital sense of responsibility, reacts. Putting aside concern for his own welfare, he steps forward to fill the void of leadership:

And Judah said to Yisrael his father, “Send the lad with me, and we will arise and go; that we may live, and not die, both we and you and also our little ones. I will be surety for him: of my hand shall you require him…” (Genesis 43: 8-9)

On the face of it, Judah offers nothing concrete to Jacob, nothing tangible to assure Benjamin’s safety. Judah offers no plan, no strategy or specific details to explain how he will fulfil his courageous pledge.

And yet, in Judah’s words there is an inexplicable quality, something difficult to define, yet palpably felt, that convinces his father. That quality, on the hasidic master’s reading, is Judah’s inner resolve, his bold confidence coupled with his modesty and simplicity. His powerful presence is what reached Jacob’s heart and awakened within him the confidence to part with his youngest son. It was Judah’s authenticity that Jacob responded to. For, in R. Ya’akov’s words, somehow, Jacob “knew that the spirit of God was speaking through him (Judah), and his heart was strengthened.”[21] He was now ready to entrust Benjamin to Judah.

Judah Approaches Joseph

Yet, in a series of bewildering events detailed in the narrative, the very worst that could have happened indeed happens. Benjamin, whom Judah vowed to protect at all cost, is accused of being a thief and taken hostage by Joseph, leaving Judah utterly distressed.

Joseph’s plotting effectively thrusts Judah into the very situation where he was long ago. Once again, a brother’s life hangs in the balance; once again, Judah is stirred to come to his aid.

At this climactic point, what follows is a rather lengthy monologue. Strikingly, throughout his speech, however, Judah does not offer any new information; he approaches Joseph without a single shred of evidence proving his brother’s innocence. How then, does Judah hope to reach Joseph’s heart? How will he convince him?

Exposed, vulnerable, and yet completely self-possessed, Judah ventures into the depths of uncertainty. In Ishbitz-Radzyn tradition, this encounter facilitates his final stage of beirur.

Judah’s Final Beirur

And Judah approached him. (Genesis 44:18)

As Judah draws closer, he is indeed standing physically before Joseph, but in his inner world, loyal to himself, he stands alone before God. With his pledge, and with his devotion to his father held firmly in his mind, he is certain of one thing only, and that is that at this moment he is doing the right thing.

Judah’s confidence does not come from certainty of the outcome; that no one can have. Rather, cleansed of self-interest, he is devoted with every fiber of his being to the safety of his brother. With nothing else to hold on to, he steps into the unknown.[22]

Judah’s heart breaks open and the words spontaneously pour out from his innermost depths: “‘Let me be a servant instead of the boy… For how can I go to my father and the boy not be with me?’” (Genesis 44:33-34).

This time it is Joseph who finds himself unprepared for the moment, for Joseph does not know the Judah who stands before him now.

He knows Judah’s former self; the charismatic leader with natural abilities and who, at the crucial moment, did not come through.

He knows the Judah who saved his life but didn’t have the moral grit to save him from slavery and bring him back to his father.

He does not know the Judah who became “one who contains nothing of himself,” a humble vessel emptied of his own self-interest who can now reflect something “other,” something beyond himself.

When confronted by this very different Judah, all of Joseph’s defenses fall away. The erstwhile master of self-control, who does not put himself at risk and does not take chances, breaks down in tears, and finally reveals himself to his brothers.

Judah’s deep humanity overwhelmed Joseph. But more than that, the peculiar power of Judah’s presence, his understanding heart, his binah ba-lev, and his deep-seated awareness that he “contained nothing of himself,” were foreign to Joseph. Yet they called to a hidden part of Joseph, a part that was concealed even from Joseph himself. Judah became like a mirror reflecting to Joseph his own compassion. When Judah approaches Joseph, the transformation within Judah ushers in a transformation within Joseph as well. The power of Judah’s presence rushed through Joseph’s veins, flooding him with an unfamiliar surge of emotion.

In a nuanced reading of the opening words of the chapter, “And Judah approached him,” R. Mordechai Yosef, in his work Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, suggests: “He penetrated into the depths of Joseph’s heart until he had no choice but to reveal himself to them [his brothers].” Such is the overpowering strength of Judah’s character that Joseph becomes helpless to resist.

Conclusion

For Mei Hashilo’ah, Joseph and Judah represent two divergent, even contrary, paths to serve God, both of them legitimate in the eyes of God. What is significant for the Ishbitz-Radzyn masters is that they represent two legitimate paths for us to follow as well.

But in the tradition, the paths of Judah and Joseph do not enjoy a peaceful co-existence; their relationship is more complex.

In truth, these two paths are always in conflict with one another, since the vital path in life that the Holy One, Blessed be He, gave to [Joseph’s offspring] Ephraim is to always know the judgement and the law for every circumstance with no exception… However, the vital life source of Judah is to always look towards the Holy One, Blessed be He, in every circumstance and not to act by rote. (Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, Vayeshev)

Joseph and Judah are archetypes for two divergent paths of avodat Hashem, and two different ways of interacting with others in the world. This reading of the narrative views the coming together of Joseph and his brothers as nothing less than a redemptive moment. It is a moment when individual biases, adaptive ways of being, and intellectual, spiritual, and emotional preferences expand to recognize the “other” as a legitimate path. This is not an analytical intellectual decision one makes; rather, it is the awareness born of realizing that different life circumstances require one path or the other.

But in a deeper application of Ishbitz-Radzyn’s teachings, both attitudes co-exist within ourselves as well, each one yielding to the other, as we aspire to a self-reflective life of personal beirur.

Joseph’s path, a life devoted to law, discipline, structure, diligence, and loyalty, is certainly indispensable for an ethical, refined life. For this reason, it is the more conventional description of a religious path.

Like Joseph’s approach, we must certainly follow the directives set out for us by the mitzvot and general principles of the Torah. But so much of life is unexpected and unpredictable. How is one to navigate one’s life in all other matters? For that, says Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, we must look towards Judah. We need to cultivate an understanding heart, binah ba-lev, an instinctive, gut feeling,[23] as R. Mordechai Yosef refers to it: the ability “to always look towards The Holy One, Blessed be He in every situation.”[24] As he continues,

Even if one understands the general direction of the law, in any event [one should] look towards the Holy One, Blessed be He, to enlighten him with the depths of the truth. (Mei HaShilo’ah, Vayeshev)

But perhaps all this is not really as radical an idea as it seems. In truth, most of life cannot be anticipated, and there are decisions that we need to make all the time.

The hasidic masters relate to biblical figures as archetypes who embody the abstract quality of their particular character traits[25] and who therefore can serve as examples of how it is possible to refine these traits. Judah’s capacity of binah ba-lev is not necessarily the exclusive territory of spiritual masters. Rather, in Ishbitz-Radzyn teaching, Judah’s way of being is recast as a fundamental spiritual consciousness every Jew needs to cultivate and live by. Like Judah, if we dare to be fully engaged in life, we may often fail, overreach, and sin. After all, cultivating an attuned heart is not an exact science.

The story of Judah offers guidelines that point the way. We saw the unexpected union of certainty and humility that Judah possesses at the end of his path. We saw how, paradoxically, only when one removes self-interest and becomes receptive like an empty vessel, can one leave oneself open to other possibilities, to the possibility of aligning oneself with God’s will.

For Judah, that means knowing that when he has exhausted the bounds of what the mind can grasp, when it seems that there is absolutely no alternative, he will cry out from the depths of his heart, and that, at times, an aperture may open and new light will flood in. This new light is the possibility that neither he nor Joseph could foresee. For what is unknown is infinitely greater than what is known.

We too may have our “Judah” moments, those occasions when necessity emboldens us to take a risk. If we cultivate a humble heart and hopeful spirit, then, as we enter into the dark, unknown places, we may uncover hidden caverns of truth, unexplored avenues for relationships, even love and fellowship, in the most unlikely of places.

[1] This article is a modified version of a chapter of my forthcoming book, Opening the Window: Hasidic Reading for Life – The Teachings of Rabbi Ya’akov Leiner of Ishbitz-Radzyn (1818-1878). My deep appreciation to my dear friends and havrutot, Judy Taubes Sterman for helping me edit this article and for her invaluable support in elucidating Ishbitz-Radzyn ideas for a broader audience, and Professor Ora Wiskind for her encouragement and inspiration in fleshing out their delicate thought.

[2] Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeshev Ya’akov.”

[3] Rashi, Genesis 38:1, s.v. “And it came to pass.”

[4] MHS, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeired Yehudah.”

[5] Mei Ha-Shilo’ah’s commentary traces the long process in which Judah repairs (mevareir) himself.

[6] Yevamot 64b.

[7] Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeshev.”

See Batya Hefter, “An Ishbitz-Radzyn Reading of the Joseph Narrative: The Light of Reason and the Flaw of Perfection,” The Lehrhaus, 2023.

[8] MHS, I, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeired.” In this reading, God’s voice, which offers a hopeful alternative narrative to Judah’s despair, is the inner voice Judah is meant to hear. R. Mordechai Yosef understands this to be implicit in the biblical narrative, in a similar way to midrashic texts, and thus his reading integrates that understanding as if it was explicitly part of the biblical narrative.

[9] Judah as a channel is paraphrased from this source. MHS, I, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeired.”

[10] MHS, I, Vayeshev, s.v. ‘vayered’.

[11] When King David, his biological and spiritual heir, is similarly confronted with a grave crime that he had thought he could get away with, he too offers a direct, unadorned confession: “I have sinned against God” (Samuel II 12:13).

[12] Judah’s very name derives from the term odeh, said by his mother Leah at the moment of his birth. While she used the term to mean “I will thank,” it also means “I will admit” or “I will acknowledge.” Biblical names signify one’s essence; Judah’s capacity to acknowledge and admit is the realization of his core, his destiny.

[13] Beit Ya’akov, Vayeshev, 40.

[14] Beit Ya’akov, Vayeshev, 40, s.v. “Vayehi ba’eit ha-hi vayeired Yehudah.” Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, II, Shemini. The notion that one’s heart, when refined, reflects the will of God, is a central idea to hasidut in general and Ishbitz-Radzyn in particular. It also appears in works of musar and in the thought of R. Kook and R. Soloveitchik, Be-sod Ha-yahid Ve-hayahad, [Hebrew], pg. 199. See introduction to my Lehrhaus article “Peshat and Beyond: How the Hasidic Masters Read the Torah.”

[15] Sefat Emet, parshat vayigash, 1887, Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, Vayehi, s.v. “vayikra.”

[16] King David is seen as the ultimate reflection of “noble humility.” Michal, the daughter of King Saul, born into privilege, cannot grasp this paradoxical quality. She scorns her husband, King David, for degrading himself, leaping and dancing with utter abandon before the Holy Ark. But David rebukes Michal for her misjudgement of his behaviour as he reveals his inner state of mind, the essence of the middah of malkhut: “I play before the Lord, and I will yet be more lightly esteemed than this, holding myself lowly…’ Our mystical tradition calls this “having nothing of his own.”

[17] Rashi, Genesis 38:26; Sotah 10b.

[18] The Torah also directs one to “love God with all of your heart” (Deuteronomy 6:5).

[19] Fishbane, Fragile Finitude, 96.

[20] The Midrash envisions Jacob reprimanding Reuben, saying, “Fool, are not your sons mine too?” (Tanhuma, Miketz).

[21] Beit Ya’akov, Miketz 39.

[22] This spiritual stance became famous in the words of King David who said, “Even when I walk into the valley of death, I will fear no evil, for I know that You are with me” (Psalms 23:4).

[23] Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, I, Emor, s.v. “Va-haveitem et ha-omer”: “understanding in the heart… This means that he has a deep and instinctive feeling for where he needs to draw his boundaries, knowing how to recognize the boundaries of God’s will, and that any further is not God’s will.”

[24] Mei Ha-Shilo’ah, I, Vayeshev, s.v. “Vayeshev Ya’akov.”

[25] In psychological terms, we may think about it as our real self being driven by our ideal self.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.