David H. Schwartz

Introduction

The Jewish calendar is structured such that the Torah reading for the Shabbat—or Shabbatot—of the holiday of Hanukkah is always about the story of Joseph. More specifically, approximately 90% of the time, the parashah of Mikeitz is read on Hanukkah, and during the rare years that it is not, it is 100% of the time the “operative” weekly parashah during the large majority of the holiday. That this confluence is guaranteed by the calendar—more specifically, the calendrical date of the historical miracle and the later rabbinically designed schedule for reading the parashot of the Torah—has long been fodder for much rich homiletics and insights.[1] Happenstance or not, the coincidence of the two certainly directs our attention to a comparison of these stories.

This essay takes a literary/structural approach toward analyzing the parallels between the Joseph story and the Hanukkah story. I suggest that, through abstract conceptual comparison based on an examination of metaphorical structures, the confluence of the stories in our calendar has the effect of eliciting what is arguably the core theological theme and message of the festival.

Miracle as Metaphor

What is the essential impetus of celebrating Hanukkah? While most Jewish holidays have a single straightforward event or theme that is being commemorated, the presence of two distinct miracles in the Hanukkah story—those of the military victory and of the long-lasting consecrated oil—complicates the focus of the celebrant and renders it difficult to identify a core theme to the holiday.[2] How are we to relate to this duality of causes for our celebration, and how do the two miracles conceptually relate to each other?

In searching for a connection between the two miracles, it helps to highlight some differences between them. First, if the military/political victory was national, geopolitical, “macro” in scope, visible to all of the inhabitants of the region, the oil miracle, for all its greatness, was a “micro” event, a ritual-focused miracle whose scope was confined to within the walls of the Temple. Second, while the miracle on the battlefield presumably had far-reaching political and social consequences for much of the Jewish population of Israel, the direct impact of the oil miracle was arguably limited and minor. Third, only the oil miracle was undeniably supernatural—i.e., miraculous—whereas ascribing the military victory to the hand of God is likely a matter of judgment and faith.

These differences in scale, impact, and character potentially point towards the conclusion, likely already intuited by many, that the connection between the miracles is one of a metaphor and its referent, or, to use more precise terminology from rhetorical theory, the “vehicle” of the metaphor and its “tenor.”[3] That is, the small and isolated event of the oil miracle is a metaphor[4] for, and thereby informs our perception of, the far-reaching event of the military miracle.

It does so first in the general sense that the contemporaneous occurrence of an overt miracle per se served as a sign to assure the Jews that the military victory was no less miraculous, even if less obviously so. Since one could have attributed the military victory to some combination of skill, luck, and any other natural explanation, God punctuated the episode with an incontrovertibly miraculous symbol, signifying that His fingerprints were on the military victory as well.[5]

But the idea of the relationship between the miracles as vehicle and tenor extends to the specific content of the miracles as well. The essence of the military miracle, as articulated in our liturgy, is the phenomenon of the small—both in number and size—overpowering the large. And at the core of the miracle of the oil, too, is the phenomenon of a small thing (an amount of oil) performing far beyond the limitations of its size. The small amount of oil is thus a direct metaphor for the few Maccabees; in both instances the small are able to defy the expectations that the course of nature would dictate.[6] By orchestrating an overtly miraculous instance of this phenomenon in the Temple after the war, then, God was conveying the message that the same essential phenomenon in the battlefield was divinely effected just the same.[7]

However, this metaphor is quite abstract and seems imperfect for the following reason. Whereas the military victory was a straightforward case of the weak and few Jews overcoming the strong and many Syrian Greeks, in the metaphor there is no direct analogue for the latter. The small oil symbolizes the Jews but, in the metaphor, its miraculously large accomplishment is not the vanquishment of a larger counterpart but the ability to last a miraculously large amount of time: one day’s worth of oil lasting a miraculous seven beyond what its size should allow. In sum, we find an awkward metaphor wherein the small lasting an exceedingly large amount of time serves as a representation of the small conquering an opponent of exceedingly large size. This is laid out in the table below.

|

Miracle |

Military |

Oil |

|

The Small |

Jews |

One day’s worth |

|

The Large |

Syrian Greeks |

Seven extra days |

|

Accomplishment |

Vanquishment of an army of large size |

Endurance over a large amount of time |

|

Abstraction |

Physical size (the weak/small conquering the strong/large) |

Duration of time |

While the abstractness of this analogy may render it less immediately obvious, the analogy is nevertheless clearly recognizable and, as such, would seem to be at least a reasonable explanation for the dual commemoration that is Hanukkah.

The Ancient and Universal Roots of Hanukkah: A Bridge Across Our Metaphor?

An examination of the little-known pre-Hasmonean roots of the holiday and its timing may help substantiate the notion of this metaphor. The Mishnah (Bikkurim 1:6) appears to attach halakhic significance on a biblical level to Hanukkah, identifying it as the deadline for the biblical obligation of the bringing of bikkurim to the Temple. Taken at face value, this would seem to imply that Hanukkah, or at least its place on the calendar,[8] has an origin and significance independent of the miracles that occurred in the second century B.C.E. While sources for this origin are scant,[9] many point out a related striking passage in the Talmud.[10] The passage describes the origin of a pagan festival, Satarnura, that is listed in the Mishnah and was celebrated for the eight days following the winter solstice. Adam, having been created in Tishrei,[11] observed during the first few months of his life that each day was shorter than the previous one, and feared that, as a result of his sin, the world must be slowly returning to darkness and, eventually, destruction. Perhaps, he feared, this is the meaning of God’s declaration that “…to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:19). This terror resulting from the progressive decrease in daylight continued into the month of Kislev, and, once in Kislev, it was perhaps exacerbated in the second half of the month, as the lunar light waned as well.[12] Once the winter solstice came, however, with its reversal of the trend of shrinking daylight hours, Adam realized that God had no such intention and therefore commemorated it thereafter as an eight-day festival.[13]

What is unstated in this passage, but seems obvious to the reader, is that this holiday—an eight-day festival occurring at the winter solstice—seems like one and the same with what we know as (i.e., what later became) Hanukkah.[14],[15] Yet, both its initiation by Adam and its link to the natural cycle of the solar calendar indicate a universal character to the roots of this festival. This is consistent with history’s account of widespread celebration during the winter solstice across many cultures,[16] including, of course, the pagan forerunner of Christmas. Indeed, the similarity between Hanukkah and the holiday known today as Christmas—occurring on the 25th day of the winter month of the solstice and touching off a period of celebration lasting at least eight days[17]—is quite striking.[18] In sum, if this light-focused holiday inaugurated by Adam is indeed the forerunner of our Festival of Lights, the two are appropriately connected thematically.

What’s more, returning to the level of abstraction implied by viewing the two miracles of Hanukkah as the vehicle and tenor of a metaphor as described in the prior section, this connection cuts right to the nexus of the two miracles. At the winter solstice, just as the growing darkness of the ever-longer nights seems like it may overwhelm the ever-shortening light of day, the “battle” turns the corner and the forces of light prevail. In the abstract, the phenomenon of the winter solstice is, on the one hand, and, like the miracle of the military victory, an instance of the small, the outmatched, the losing—here, the daylight—turning the corner to overcome the large and the daunting—the night.[19] Yet, on the other hand, and, as with respect to the oil miracle, the “small” and “large” of the winter solstice are descriptions not of physical size but of temporal duration, and more specifically duration of a period of light, to boot. Thus, Adam’s holiday sits right at the intersection of the abstract concepts underlying the two Hanukkah miracles.

While these connections are quite abstract, the celestial imagery inherent in the time of year of Hanukkah, whether or not rooted in Adam’s ancient celebration, does seem to lend some credence to the otherwise awkward structure suggested above for conceiving of the two miracles of Hanukkah as vehicle and tenor. By bridging some of the gap between the two abstract concepts embodied by the two miracles—that is, the gap between the concepts of the small overcoming the large and of the small lasting an extra large period of time—the calendrical timing of the festival perhaps strengthens my hypothesis as to the common denominator between them. The small overcoming and defying natural expectations is the unified theme inherent in both the vehicle (the oil miracle) and its tenor (the military one). Accordingly, the overtly miraculous nature of the symbol is intended to remind us of God’s involvement in the less overtly miraculous military victory that it symbolizes. Still, further support, and precedent, for the level of abstraction inherent in my analysis seems warranted.

Mikeitz

As it happens, such a precedent can be found in Parshat Mikeitz. First, and most simply, the aforementioned coincidence of Hanukkah with the Torah reading of Mikeitz complements the discussion in the previous section as an additional, related, connection between the theme of Hanukkah and its place on the calendar. The fact that the part of the Joseph story that always lines up with Hanukkah—just when his string of misfortunes turn the corner and, beginning with Pharaoh’s dreams, his prospects go from bleak to bright[20]—is, albeit abstractly, parallel to the image of darkness giving way to light inherent in the winter solstice.

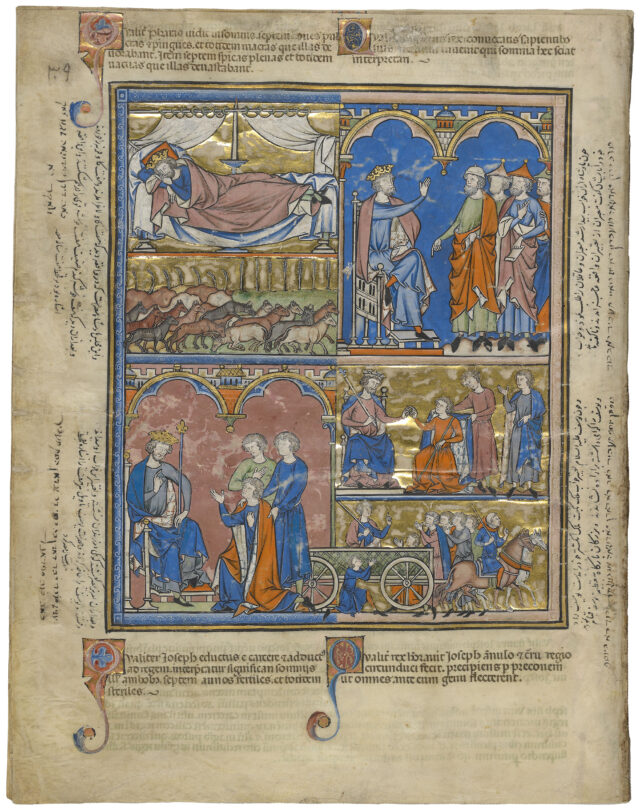

But the precedent is much more specific than that. As I will explain, the opening story of Mikeitz, Pharaoh’s dream and the years of plenty/famine, provides us with a precedent and validation for precisely the type of abstract conceptualization I utilized in justifying the perception of the two miracles of Hanukkah as the vehicle and tenor of a metaphor. Our analytical focus in this essay has been miracles – and Mikeitz contains a large one. At its core, the event of Pharaoh’s dreams and Joseph’s interpretation, together with the corresponding years of plenty, were nothing less than a miracle enabling Joseph and the Egyptians to arrange that seven years of famine would miraculously be sustained by food which, absent the miracle, would have lasted only one year. Had there been no years of plenty, no prophetic dream, and had Joseph not been granted the power to interpret it, the food—humanity’s fuel—of the year before the famine would have been squandered and would have lasted only for that one year itself, only to leave seven subsequent years of lacking.

Let me elucidate this point by highlighting how each element of said miracle was necessary. Obviously, had there been no years of plenty, there would not have been a surplus of food to service the seven years of famine. But even with the seven miraculous years of plenty, had there been no miraculous dream and interpretation, there would have been no foresight to store the food in the cities, leaving each year’s food (indulged in, but ultimately) squandered during that year itself. Thus, in that scenario, the food that was present in the seventh year of plenty effectively would have lasted only for the seventh year itself—whereas in our actual, miraculous scenario, the food that was extant during the seventh year (which is also now a lot more food, thanks to the aforementioned miraculous insights) was enough to last for the subsequent seven years of famine as well. Thus, only due to God’s miraculous engineering of events was Egypt able to obtain the result that the food that was present in the year before the famine was able to last for an additional seven years.

This is underscored by a close reading of the oft-ignored verses describing the playing out of the events predicted by Joseph. See the subtle contrast indicated in the following two verses:

The seven years of abundance that the land of Egypt enjoyed came to an end, and the seven years of famine set in, just as Joseph had foretold. There was famine in all [the] lands… Genesis 41:53-54 (translation from Sefaria; emphasis my own)

As Nachmanides (on 41:2) observes, the simple reading of the verses indicates that while the famine was universal and not limited to the Egyptian borders, the years of plenty were a local event. Thus, the episode can be viewed as a miraculous solution to the “default” worldwide problem of the famine. The famine was an impending global event that was to strike the world irrespective of Joseph’s presence in Egypt or Pharaoh’s dreams. By contrast, the years of plenty were, apparently, a special, miraculous occurrence limited to Egypt as a result of Joseph’s being there. In the natural course of events, absent Divine intervention, the year before the famine began there would have been no surplus of food for the upcoming years—perhaps because the land would not have produced any extra, but certainly because without the foresight miraculously provided by the dreams and Joseph’s prophetic interpretation thereof, there would have been no impetus to store the surplus for the future. Thus, the years of plenty were, together with the dreams and interpretation provided by Joseph, the necessary miracle enabling Joseph and Egypt to save the world in the face of the famine—all working to ensure that the food present in the year before the famine would be sufficient to last a miraculous additional seven years.

By definition, any interpreted dream is a metaphor. Or to use our above terminology, a dream is the vehicle and its interpretation is the tenor.[21] And what is the chosen metaphoric vehicle for the above course of events? In a nutshell, Pharaoh’s dreams are about nothing other than the weak conquering the strong. The small, scrawny cows, and the thin and withered sheaves, vanquish their large and brawny counterparts.

Yet, Pharaoh’s dreams as a metaphor for the above are, again and quite similarly, indirect and awkwardly abstract. Instead of images of time periods of abundance and time periods of absence, the chosen metaphor is one of opponents of large and small size. That is, seven years of famine are symbolized not, for example, by seven days or seven hours of absence, but by seven weak and small cows or sheaves, which overcome seven larger adversaries. We are thus left with the following matrix of metaphor and interpretation[22]:

|

|

Dream |

Interpretation |

|

The Small |

Weak cows/sheaves |

One year’s worth of food (absent the miracle) |

|

The Large |

Large cows/sheaves |

Seven extra years |

|

Accomplishment |

Vanquishment of counterparts of large size |

Endurance over a large amount of time |

|

Abstraction |

Physical size (the weak/small conquering the strong/large) |

Duration of time |

Hence, the exact same level and type of abstraction described earlier—which may have given us pause in drawing the above conclusions about the connection between the two miracles of Hanukkah—is validated by its appearance in Mikeitz, where not only does the same correspondence appear, but it is overtly “labeled” as a correspondence, insofar as it is presented in the form of a dream and the normative interpretation of that dream.[23] Clearly, we have a well-timed precedent for applying precisely the same type of abstraction in drawing the conclusion that the two miracles of Hanukkah are intended as a mashal and nimshal, a vehicle and tenor—notwithstanding the awkwardness or seeming incongruity of the comparison of size with time duration—with the message being that we should recognize the military victory of the few and weak Jews over their larger and stronger rivals as a miracle engineered by God, contrary to the natural order of things.

These parallel structures are summed up by the following table:

|

|

Mikeitz |

Hanukkah |

|

Small and weak miraculously overcoming large and strong |

Weak and small cows/sheaves vs. robust cows/sheaves |

Weak and small Jewish army vs. strong Syrian Greeks[24] |

|

Small provision lasting a miraculously long time |

Food lasting seven extra years |

Oil lasting seven extra days |

|

How is the latter miracle engineered? |

years of plenty, dream, prophetic interpretation |

Unknown |

|

Relevance of a seven-unit time period |

Food would be replenished following a seven-year famine |

Procuring replenishment oil would take seven additional days[25] |

|

Connection between the two events |

Row 1 symbolizes row 2 |

Row 2 symbolizes row 1 |

Thus, the concordance of these metaphorical structures in Parashat Mikeitz and Hanukkah highlights and helps confirm our interpretation of the dual miracle, as described above. This is in turn only further bolstered by the coincidence of Parashat Mikeitz with Hanukkah in our calendar.

Conclusion

We have thus seen that the confluence of the days of Hanukkah with the reading of Parashat Mikeitz not only highlights, but also validates, our interpretation of the phenomenon of dual miracles underlying the holiday. The “micro-” miracle of the oil was indeed the sign—in the form of a metaphor—that the “macro-” event of the military victory was similarly miraculous. And lest one suspect that the parallelism between the vehicle and tenor of this metaphor is too asymmetric or imperfect to ring true, we have the story of Joseph and Pharaoh’s dreams in Parashat Mikeitz providing precisely the same conceptual structure, the exact same relationship between vehicle and tenor, to dispel any such doubt.

Even if perfectly validated, however, how are we to understand this choice of such an awkward conceptual connection between vehicle and tenor? Would not a more simple, symmetrical, elegant parallel between them work even better than an imperfect one that needs to be (even if it is) authenticated by a Biblical precedent? Here is where the ancient roots of the holiday come in, providing its message which bridges the gap between the conceptual structures of its two miracles: the universal message of light being able to overcome darkness.

[1] This confluence arguably receives an implicit nod already in the Talmud. The passage that provides our only talmudic recounting of the Hanukkah miracle and most extensive discussion of its laws is cryptically interrupted by an apparent non sequitur about the Joseph story—albeit in reference to a verse from Parashat Vayeishev rather than Mikeitz. See Shabbat 22a.

Aside from the ideas provided in this essay, other thematic parallels between the holiday and Parashat Mikeitz abound, including the themes of staying true to one’s roots in the face of a foreign (Egyptian/Hellenistic) culture; and of a band of brothers engaging in a dangerous mission.

[2] This difficulty is subtly manifested in the divergent descriptions of the meaning of Hanukkah as presented in two of our canonical sources on this issue. Whereas the al ha-nissim insertion for Hanukkah in our thrice-daily prayers is almost exclusively about the miraculous military victory over the Syrian Greeks, the Talmud’s answer to the direct question, “Mai Hanukkah,” or “What is Hanukkah?” all but ignores the miracle of the Maccabees and focuses almost exclusively on the miracle of the oil, other than a reference in passing, solely in the context of the timing of the oil miracle, to “when the Hasmoneans overcame and defeated [the Greeks]” (Shabbat 21b; cf. Megillat Ta’anit ch. 9). While these distinct approaches are at least partially explained by their context—an analysis beyond the scope of this essay—the fact that two primary sources are so completely divergent underscores the difficulty one has in isolating a unitary theme and message of the day.

[3] This nomenclature was coined by I.A. Richard in The Philosophy of Rhetoric (Oxford University Press, 1936), 96-100. See also Dann L. Pierce, Rhetorical Criticism and Theory in Practice (McGraw-Hill, 2003), 148, 353. In Shakespeare’s “All the World’s a Stage” metaphor, for example, the “vehicle” is a stage, and the “tenor” is the world. Alternative nomenclatures include Max Black’s “subsidiary subject” and “principal subject,” Max Black, Models and Metaphors: Studies in Language and Philosophy (Cornell University Press, 1962), 31-33.

[4] The use of the term “metaphor” here is intended to refer to its role in our conceptual framework, not, of course, to suggest that the miracle of the oil did not literally happen.

[5] As pointed out by R. Yaakov Medan, this idea is conveyed by the angel to the prophet in Zechariah 4:1-6. See https://www.hatanakh.com/sites/herzog/files/herzog/The%20Miracle%20of%20the%20Oil%20and%20the%20History%20of%20Chanuka-Medan.pdf. See also Maharal’s Ner Mitzvah II:9. More generally, this approach is an instantiation of the principle formulated by Nachmanides (Exodus 13:16): “Through the great open miracles, one comes to admit the hidden miracles which constitute the foundation of the whole Torah…”

[6] Cf. Michael Rosenberg, “From Leviticus to Latkes: The Origins of Hanukkah’s

Miraculous Oil and the Meaning of the Festival,” in Ariel Evan Mayse and Arthur Green, eds., Be-Ron Yahad: Studies in Jewish Thought and Theology in Honor of Nehemia Polen (Boston, 2019), 101.

[7] An implication of such an analysis would be that the main, or essential, theme or driver of the holiday of Hanukkah is the military victory; the miracle of the oil is a derivative of, or ancillary, to it. This is arguably supported by the focus on the former in al ha-nissim, a prayer whose ostensible objective is simply to articulate the miracle, and essence, of the day. (This in contrast to the talmudic passage, whose focus in asking “Mai Hanukkah” can be understood as asking specifically about the idea underlying the mitzvah of lighting Hanukkah candles). Further, one might even suggest that the structure of the al ha-nissim prayer itself obliquely makes this point: after overwhelmingly focusing on the military miracle—our tenor—it briefly concludes—or seals the point it is making—with a reference to the oil miracle—our vehicle.

[8] Sifrei derives the Hanukkah deadline from the verse, “…which you harvest from the land” (Deuteronomy 26:2), as follows: “So long as [the fruits] are found on the face of your land, [you may bring bikkurim].” Hanukkah marks the very end of the harvest season. Thus, at the very least, the specific time of year that Hanukkah takes place has significance on a biblical level. R. Yoel Bin-Nun has noted that it is particularly the olive season which (is the last of the fruit harvests and) ends at that time of year. See his “Yom Yisud Heichal Hashem (al pi Nevuot Haggai VeZechariah, Megadim 12 (1990)), 49-97, an updated version of which is available at http://files8.design-editor.com/92/9266067/UploadedFiles/C5537A3D-5642-60A3-2A0D-C4D9B89312C4.pdf, and available in English at https://www.hatanakh.com/sites/herzog/files/herzog/The%20Secret%20of%20Chanuka%20as%20Revealed%20by%20the%20Prophecies%20of%20Haggai%20and%20Zechariah.pdf. Thus, much like the biblical three festivals, Hanukkah also has a dual character: historical-national but also natural/religio-agricultural. Ibid.

[9] One famous example is the view that the mishkan was completed on the first day of Hanukkah, Pesikta Rabbati 6 (cited by the Tur, OC 684) and Bamidbar Rabbah 13:2. Perhaps relatedly, the foundation to the Second Temple was laid on the 24th day of Kislev, (Haggai 2:18), or, on R. Yoel Bin-Nun’s reading, ibid., on the 25th day itself.

[10] Avodah Zarah 8a. Cf. Avot de-Rebbi Natan 1:8.

[11] Following, implicitly, the opinion of R. Eliezer in Rosh Ha-Shanah 10b, who disagrees with R. Yehoshua’s view that he was created in Nisan.

[12] R. Yoel Bin-Nun, ibid.

[13] The passage concludes that while Adam’s intentions were worthy and (the passage implies) the holiday began on valid footing, it was later co-opted by pagans and converted into an idolatrous festival.

[14] The version of this midrash in Avot de-Rebbi Natan (1:8) also adds that Adam reacted to this experience by building an altar—perhaps reminiscent of the Temple dedication that is Hanukkah.

[15] This hypothesis arguably—and ironically—finds, effectively, support in the claim among some scholars that the festival of Hanukkah was not originally Jewish but was borrowed from the pagan world. See Zeitlin, above, 1-2, and especially the sources cited therein in notes 2 and 12.

[16] While there are too many to provide an exhaustive listing here, the following are some examples (besides, of course, Christmas and Hanukkah): Makar Sankranti is a holiday in the Hindu calendar marking the end of the month of the winter solstice; Dongzhi is a traditional holiday of China in the peak of winter; Toji is celebrated with huge bonfires in Japan; for ancient Persians and contemporary Iranians there is Yalda Night on the darkest night of the year, when they light fires; ancient Norse traditions included lighting fires to ward off spirits during the longest night of the year, celebrated today with girls wearing wreaths of candles on their heads; Soyal is the winter solstice festival of the Hopi Native American tribe, celebrated with the kindling of fires; and Shalako is celebrated by the Zuni, one of the Native American Pueblo tribes in New Mexico. In addition, in the Southern Hemisphere, where the winter solstice occurs in June rather than December, the Incas celebrated Inti Raymi in honor of the sun god. See, e.g., https://www.britannica.com/list/7-winter-solstice-celebrations-from-around-the-world and https://www.history.com/news/8-winter-solstice-celebrations-around-the-world. Several of these festivals are particularly focused around farmers, for obvious reasons; this can add a dimension to how we understand the bikkurim aspect of Hanukkah described above.

[17] The Twelve Days of Christmas last through January 5th. The 8th day, however, is celebrated in particular for a variety of reasons, including as the commemoration of the circumcision of Jesus.

[18] There is no mention in the gospels, nor in any truly historical resource, of the date of the birth of Jesus. The earliest source associating December 25th with his birth is likely in the early 3rd century, appearing in the commentary on Daniel by early theologian Hippolytus of Rome. See Thomas Coffman Schmidt ed., Hippolytus of Rome: Commentary on Daniel (2010), Appendix 1. It was not officially put forward until approximately 350 C.E. by Pope Julius I.

Prior to the advent of Christianity, winter and solstice festivals were widespread in many European pagan cultures. The Anglo-Saxons and other pre-Christian Germanic peoples celebrated a winter festival called Yule. See “Christmas – An Ancient Holiday,” The History Channel, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20070509030721/http://www.history.com/minisites/christmas/viewPage?pageId=1252. In addition, after the time of Jesus but before December 25th was identified by the Church, there was a widespread custom among Roman pagans to kindle lights to honor the sun god and celebrate the birthday of the sun on that date, Susan K. Roll, Toward the Origins of Christmas (Peeters Publishers, 1995), 133. While there are many competing theories as to why the Church selected December 25th as the date to associate with Jesus’s birth, it has long been suggested that this was done in order to correspond with this pre-existing pagan solstice holiday. Roll, 130.

[19] That the “small” and “large” of the Hasmonean miracle—the Jewish and Greek forces, respectively—are easily figuratively describable as forces of light and darkness in a spiritual sense, further bolsters this comparison.

[20] Indeed, the fact that the Shabbat of Hanukkah is almost always the parashah of Mikeitz, which begins with this turn in Joseph’s fortunes, but occasionally is the parashah of Vayeishev, which describes his spiral downward and ends with him at his lowest point, ensures that our biblical focus during Hanukkah is precisely on this turning point in the Joseph story.

[21] Whereas our approach to the relationship between the two Hanukkah miracles, suggesting that they constitute the tenor and vehicle of a metaphor was conjecture, the same cannot be said about the relationship between a dream and its interpretation, which is unassailably identified as such.

[22] Joseph explains to Pharaoh that the seven fat cows symbolize seven years of plenty, while the seven lean and weak cows symbolize the seven years of famine; consumption of the former by the latter, while not overtly addressed by Joseph, is assumed to refer to the fact that the famine will be so devastating that it will either fully deplete the produce from the years of plenty (see Nachmanides, 41:4) or will overwhelm memories of the years of plenty in the national consciousness (see Rashi, 41:4). However, this explanation gives rise to the anomalous result that the interpretation of the dreams ends up as “counterfactual”: the state of affairs predicted by Joseph does not, in fact, come to fruition, and this is precisely because of the remedy suggested by Joseph as a result of this otherwise accurate interpretation. Having become aware of the impending catastrophe, Joseph recommends storing the food from the years of plenty for the famine years, and thereby prevents the very devastation foretold by the dreams. Whether it is problematic or even paradoxical that, consequently, the interpretation propounded by Joseph ends up being effectively false, is debatable. But in any case, the alternative, parallel interpretation described in the immediately following table holds true even in (and indeed becomes true because of) the remedied state of affairs brought about by this solution.

[23] Note also Bekhor Shor’s comment (41:7) on the need for Pharaoh’s second dream, which is quite striking given the structure we have laid out:

“And it appears to me: That both dreams were necessary to understand the interpretation well. For if he saw the incident of the cows, it would appear: at the end of seven years or seven months a weak nation would prevail over a great nation and beat them and exile them. Because the nations are called cows, as it is written: “Listen to this word, you cows of Bashan” (Amos 4:1), and like: “Egypt is a {very beautiful} heifer” (Jeremiah 46:20), and that they ate them is a sign that they will consume them, like: “for they have devoured Jacob” (Jeremiah 10:25). But when he saw the ears of grain, the interpretation became known, [that the dreams spoke] of plenty and famine… And [when] Joseph said: “About the repetition of the dream {etc.} that God is hastening to do it” (Genesis 41:32), he was not concerned to reveal to them these things. For if it was only for the haste of events, he should have seen a single version twice in [only one] dream.” Translation from alhatorah.org (emphasis mine).

[24] As described in al ha-nissim: “You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few…” Translation from chabad.org.

[25] The Talmud is silent as to the need at that time for specifically eight days of burning. Later authorities speculate that this timeframe was a function of either the time the Jews needed to purify themselves in order to prepare fresh, pure oil (Beit Yosef , OC 670; this also seems to be the implication of Rambam in Mishneh Torah, Laws of Hanukkah 3:2) or of the distance from the location where pure oil was available (Rav Hai Gaon cited in Teshuvot Ha-Geonim, Lyck 104; Ran cited by Beit Yosef; Meiri, Shabbat 21b).

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.