Nachman Levine

It started with blintzes. I’m not saying this to be clever; it’s simply what happened. A cursory review of the laws and customs of eating milchigs (dairy foods) on Shavuot in its sources in the halakhic literature led me, in a happy series of events over time, to the 12th-century Rhineland (so to speak), collective and personal revelation at Sinai, the classic eastern European heder, a scathing critique—by a protégé—of Gershom Scholom’s “anarchistic,” “antinomian,” “nihilistic” reading of a teaching of the Rimanover Rebbe, to an early 19th-century heder setting, and again, Sinai.

And, significantly, back to the heder. And blintzes.

My interest here is in the forms of an idea, of the imagery and actuality of the relevance of blintzes and the heder as experience or metaphor in relation to the revelation at Sinai. The historical and theological background of these will have bearing on contemporary polemical issues of “ongoing revelation”—or non-revelation—at Sinai. Their significance is in how minhagei Yisrael’s significations and meanings—or, more importantly, their experience—continue to have deeply layered, concretized meaning for us.

Milchigs and Hakhnasah Le-Heder

Here’s what happened. My focus was on blintzes and the custom of eating milchigs on Shavuot. Reading the halakhic sources about this, I had what I thought was a startling discovery (it turns out it had already been suggested[1]) about its true origin. While there are, to be sure, some 150 fascinating explanations for the minhag,[2] the more explanations that are given only serve to create the impression that they are all true and beautiful—but not originary.

The practice of eating milchigs on Shavuot is actually a historical vestige of the ancient Hakhnasah Le-Heder custom practiced in the medieval Rhineland or Carolingian Jewish world, of bringing a child to begin his study of Torah on Shavuot itself—just as the Jewish people did at Sinai, as articulated in the custom’s sources (see below). The Hakhnasah Le-Heder ritual focused on a child being given a milk-and-honey cake with pesukim and the Aleph-Beit on it to experience the Torah’s sweetness as he would begin the study of Torah. No medieval halakhic authority before the 11th-12th centuries is cited in the literature; all are Ashkenazic,[3] and the custom’s repeatedly cited proof text is Song of Songs 4:11: “Honey and milk are under your tongue.”

The detailed custom appears in R. Elazar b. Yehudah’s 12th-century Sefer Rokeah (Hilkhot Shavuot 296) as “the [ancient] custom of our forefathers,” in which the child would be brought to synagogue to begin study of Torah on Shavuot as equivalent to mattan Torah itself—“since the Torah was given on that day”—and would be given a milk-and-honey cake with pesukim on it:

The [ancient] custom of our forefathers is that we have the little children begin to study Torah on Shavuot, since on that day the Torah was given. . . . we bring the little children [to the synagogue] at daybreak on Shavuot, since it says, “In the morning there was thunder and lightning” (Exodus 19:16) . . . and we cover the child with a garment, as it says, “And they stood beneath the mountain” (Exodus 19:17). We bring him a tablet on which is written [the first and last four Aleph-Beit letters forwards and backwards] and “Torah tzivah lanu Moshe” (Deuteronomy 33:4) and “Torah tehei emanuti” (Siddur) and “vayikra el Moshe” (Leviticus 1:1). The Rav reads every letter of the Aleph-Beit and the child repeats it—and similarly, the verses. And he puts a little bit of honey on the tablet, and the child licks the honey on every letter, and then they bring him a cake kneaded in honey on which is written: “My Sovereign God gave me a skilled tongue to know” . . . (Isaiah 50:4), and the Rav reads every letter of those verses, and the child [reads] after him.

Before that, Rashi’s disciple, R. Simhah of Vitry (11th century), explains the custom citing Song of Songs 4:1:

And why do we knead the cakes in milk and honey . . . ? Since it says, “Honey and milk are under your tongue.” And when a person brings his son into the Talmud Torah, we write the [Aleph-Beit] letters on a tablet . . . and then we cover them with honey, and we feed him cakes made with honey. Know that the matter is as if he brought him before Har Sinai. (Mahzor Vitri, Laws of Circumcision 508)

In the 13th-century Sefer Minhagim of R. Meir b. Barukh of Rottenburg (Minhagei Shavuot):[4]

We have the custom to make cakes for the young children who begin to study Torah, and we write on them verses to open their hearts, and they eat them in the synagogue.

The custom and its proof text, “Honey and milk are under your tongue,” are cited in R. Eliezer b. Yoel Ha-Levi’s 13th-century Avi Ezri. It is also cited by R. Aharon b. Yaakov (13th-14th centuries) in his Orhot Hayyim (Hilkhot Tefilat Ha-Moadim):

We have the custom of eating honey and milk on the first day of Shavuot, since the Torah is compared to honey and milk, as it says: “Honey and milk are under your tongue.”

It also appears in the 14th-century Kol Bo (53 and 74):

We also have the custom to eat honey and milk on the holiday of Shavuot, since the Torah is compared to honey and milk, as it says: “Honey and milk are under your tongue.”

Beyond the biblical simile of Torah as “sweeter than honey”—“More desirable than gold . . . and sweeter than honey and drippings of honeycomb” (Psalms 19:11); “How pleasing is Your word to my palate, sweeter than honey” (Psalms 119:103)—tasting the milk-and-honey cake’s pesukim was as if experiencing the Torah’s sweetness itself in the custom’s proof text (Kol Bo 52: “Since it says, ‘Honey and milk are under your tongue’). Some midrashim[5] read this verse as an allegory for the experience of Torah; Tanhuma (Buber) Ki Tisa 9 even reads it as the original experience of mattan Torah itself:

When Israel stood before Mount Sinai and said, “All that G-d spoke, we will do and we will listen” (Exodus 24:7), the Holy One Blessed Be He said to them, “Honey and milk are under your tongue.”

Over time, the Shavuot Hakhnasah Le-Heder practice disappeared (R. Shabbetai Kohen, 17th century; Siftei Kohen, Yoreh Deah 245:8), and the abandoning of the Hakhnasah Le-Heder customs in general was lamented (R. Yaakov Emden, Migdal Oz). Several elements—e.g., wrapping the child in a tallit, putting honey on the Aleph-Beit letters, etc.—have been reinstated, largely adopted in the general Jewish public and particularly within the Hasidic practice known as the “Areinfirinish” (Yiddish for ‘bringing in’—‘Hakhnasah’—[to the Heder]).

My sense was that the Hakhnasah Le-Heder, together with its honied Aleph-Beit letters cited extensively in Sefer Rokeah, Avi Ezri, Orhot Hayyim, Kol Bo, etc.,[6] [7] migrated eventually to the child’s third birthday[8] or September and the beginning of the school year.[9]

And the blintzes, the milk-and-honey cake (“honey and milk are under your tongue”), stayed in place on Shavuot.[10]

The Jewish People’s Hakhnasah Le-Heder

The medieval sources (Rokeah, Mahzor Vitry, Kol Bo, etc.) repeatedly stress that the Hakhnasah Le-Heder custom was held on Shavuot because on that day Israel received the Torah. Shavuot effectively celebrates the Jewish people’s own archetypal Hakhnasah Le-Heder at mattan Torah.

The imagery of Sinai as a classroom does appear already in Tanhuma (Buber) Yitro 16’s variant on Mekhilta, Yitro DeBahodesh 5, that God announced at Sinai, “I [“Anokhi”] am the Lord your God”, “Since He appeared to them at the Sea as a strong warrior [“God is a man of War” (Exodus 15:3)] and at Sinai as a Humash teacher who teaches Torah . . . He taught them Torah and stood before them as a scribe.” The combined imagery in this variant on the Mekhilta’s version, “He appeared at Sinai as a old man full of mercy” conveys that of a kindly Humash teacher at Sinai.

Hakhnasah Le-Heder Transformed

The conceptual reversal of the personal Shavuot Hakhnasah Le-Heder custom to that of Israel’s collective Hakhnasah Le-Heder at Sinai was already formulated by the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe (R. Yosef Yitzhak Schneerson, 1880-1950):[11]

At mattan Torah, G-d Blessed Be He took 600,000 men[12], besides old people, women, and children, and brought them in a “Cheider” to say ‘Qamatz Aleph A’, as it says, (Song of Songs 1:4) “The king has brought me to his ‘chambers’ [‘Hadarav’: ‘his “Heders’”], we will be glad and rejoice in You” [in Hebrew: ‘Bach’: Beit Chaf, the numerical equivalent of the Aleph-Beit’s 22 letters], as the first letter that G-d Blessed be He said was ‘Qamatz Aleph A’ of the word “Anokhi”.

Moreover, he startlingly reverses it back again from there to a Jewish child’s personal Hakhnasah Le-Heder in the context of eastern European heder practices. In a letter (Igerot Kodesh VII, p. 146), he invokes the poetic imagery as a concrete archetype to argue for preserving the traditional heder’s method of learning the Aleph-Beit in the face of modernity. In this way, the collective heder experience at Sinai is replicated back into a child’s personal Hakhnasah Le-Heder.

There is a tradition we have from our holy fathers, our teachers [the Habad Rebbes before him], received from father to son, from generation to generation from ancient generations, about the reason for beginning the study of Torah with the Tinoqot Shel Bet Raban [heder children] with the letter Aleph with its Nikud of a Qamatz as: ‘Qamatz Aleph A’, as commemoration of the receiving the Torah at Sinai, where the Holy One Blessed Be He opened the First Statement [of the First Commandment] with the letter Aleph in the Nikud of Qamatz. That is to say, the Hakhnasah Le-Heder, bringing a child into heder is [his own] mattan Torah, and as elaborated in one of the books of the Rishonim [presumably the Rokeah]. How much holiness in pure faith is established in the child’s heart in knowing that his Hakhnasah Le-Heder is his personal mattan Torah . . . as just as there, we begin learning with him the first letter Aleph with the Nikud of a Qamatz as ‘Qamatz Aleph A’.

The Rimanover’s Teaching

All this however brings us to a fiery polemic debate about Gershon Scholem’s “anarchistic,” “antinomian,” “nihilistic” (the diatribes get worse) reading of a teaching of the Rimanover Rebbe (R. Menaḥem Mendel of Rimanov, 1745–1815) about the revelation (for Scholem, the foundational non-revelation) at Sinai. In Scholem’s understanding of that teaching, the revelation at Sinai consisted only of the first letter Aleph of the word “Anokhi” of the First Commandment, thus essentially inaudible or inchoate: “without specific meaning” (On the Kabalah and its Symbolism, 30).

In the ensuing critique by Scholem’s protégé Moshe Idel the experience of the 19th-century Heder is invoked as significantly salient.

The teaching Scholem adduces was gleaned second-hand from Aharon Marcus’ Der Chassidismus (1901), that cites the teaching and reads it in the context of Maimonides’ Guide to the Perplexed, of the rational as independent of prophecy. What the Rimanover may have actually said is reported by his disciple, R. Naftali Tzvi of Ropshitz (1760-1827):

“I heard from my Master, the Rebbe of Rimanov on the verse: “God spoke once [or “One” = Aleph) (Psalms 60:12), that it is possible that we did not hear from the Mouth of the Holy One Blessed be He but only the letter Aleph of ‘Anokhi’. (Zera` Kodesh, Shavuot)

Idel thus notes[13] that the Hasidic masters “were hardly harbingers” of “minimalist,” “anarchic speculations”, or Nietzschian “theories of negativity,” but that:

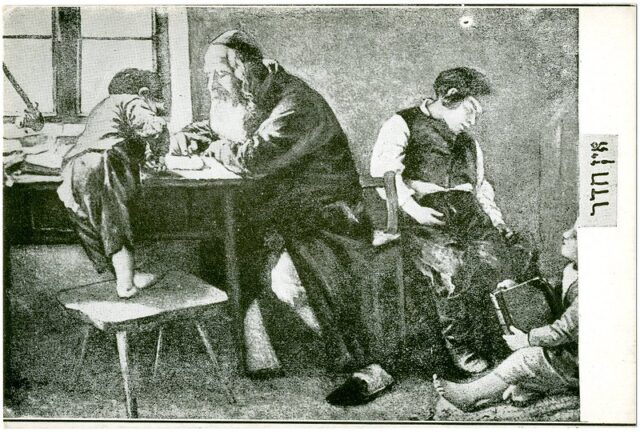

“The phrase Qamatz Aleph” . . . in the formulation of the three Hasidic masters . . . is constituted by two words by which every Eastern European[14] Jewish male child started to learn Hebrew at the age of three. The sonorous ambience that accompanies the child’s collective recitation of those two words . . . is quintessential for understanding the underlying background of the Hasidic discussions about the revelation at Sinai . . . It was the Heder setting, in which the teacher pronounced “Qamatz Aleph A” and the small children repeated it loudly, that the Hasidic masters had in mind and transposed to Sinai . . . Instead of the solemn silence of inchoate revelation . . . as Scholem assumes, we have here the sonorous community of the teacher, the melammed, who is projected on high as God, and the Israelites in the role of children.”

Scholem’s reading of inaudible revelation is also critiqued by Yehudah Jerome Gellman[15], philosophy professor at Ben-Gurion University as invoked by Benjamin Sommer[16], a JTS Bible professor who uses the Rimanover’s teaching as a basis for justifying Bible criticism from Sinai. Idel and Gellman both point out that the other versions and interpretations of the Rimanover’s teaching in the Ropshitzer’s works, as well as by his son-in-law, the next Ropshitzer Rebbe, refer not to a silent revelation, but several times explicitly, to: “Qamatz Aleph.”

In One Word, Or Letter

What emerges in the critique is that for the Rimanover, the Aleph at Sinai was not inaudible, “non-verbal” (Sommer), without content. More specifically, Gellman and Warren Zeev Harvey[17] argue, the teaching’s connection to the sonorous “Qamatz Aleph A” must be understood in the context of classic Jewish thought about the Ten Commandments at Sinai containing and subsuming the entire Torah.

The idea is clearly developed in Talmudic and mystical sources. The Mekhilta (Yitro, DeVaHodesh 4)[18] describes God as saying all Ten Commandments first “in one utterance,” and then individually, and (DeVaHodesh 7) that even the subsequent individuated commandments “Remember the Sabbath” (Exod. 20:8) and “Guard the Sabbath” (Deut. 5:12)[19] were said in “in one utterance.” Talmud Bavli, Makot 24b and Horayot 8a, brings a further position that we heard directly from God only its first two Commandments (“I am the Lord your God . . .”; You shall have no other gods . . . ”), since when the experience was too powerful for Israel, “My soul went out in His speaking with me” (Song of Songs 6:6), Moshe taught the rest as they appear in the third person (Bavli Shabbat 88b) based on Deut. 5:20-26. Halakhic authorities thus note[20] how both of the Mekhilta’s two versions of “in one utterance” at mattan Torah are replicated and reenacted in the Aseret HaDibrot Torah Reading on Shavuot with its Ta’am HaElyon cantillating the first two Commandments (“I am the Lord your God . . .”/“You shall have no other gods”) as one verse and the four verse Shabbat Commandment as one.

The further developed idea that all 613 Mitzvot were contained in the Ten Commandments appears in one form or another in Philo[21], R. Moshe HaDarshan (11th century)[22], the medieval Midrash Agadah[23], and R. Saadiah Gaon’s Commentary to Sefer Yetzirah and his liturgical Shavuot poem, “Anokhi Eish Okhelah, an “Azharah”[24] which in an exegetical context Rashi (Exod. 24:12) cites that the Aseret HaDibrot contained all 613 Mitzvot.

From there in mystical and Hassidic teachings, which the Rimanover certainly knew, comes the idea that all positive and negative commandments were contained in the first two Commandments (“I am the Lord your God . . .”; You shall have no other gods . . .”) (R. Yeshayahu Hurvitz, Shnei Luhot HaBrit, Torah Or, Yitro; R. Shneor Zalman of Liadi, Likutei Amarim 20, “since only these we heard, since they contain the entire Torah.”[25]) The idea is extended through the Zohar, II:85b (and 90b), to the Ba’al Shem Tov[26], and Mezeritcher Magid[27], that all the Torah’s commandments were contained in the Aseret HaDibrot’s first word, “Anokhi”. The Magid’s student, Rabbi Pinhas HaLevi Horowitz (Panim Yafot, Yitro) extends this to the entire Torah being contained in the Aleph of ‘Anokhi’.[28]

“(Non)Verbal Revelation” and “Ongoing Revelation”

Extensive discussion and debate (citing the Riminovor among others) has proliferated about what’s been described as a progressive “Ongoing Revelation” as a resultant corollary of a “Non-Verbal Revelation” at Sinai, such that effectively the Torah is not from Heaven but developed by humans. It’s been largely brought to the fore in the Conservative Movement[29] where the primary issue appears to be Bible criticism (and in Halakhic Egalitarian circles, a programmatic subtext of adjusting the Torah to contemporary mores). Since B. Sommer and others deny that the text of the Torah is from Heaven, they argue for an “ongoing revelation.” Since the revelation at Sinai was ineffable and inaudible, they argue, (citing the Rimanover, Rosenzweig[30], and A.J. Heschel’s comment that “the Bible is a midrash on the experience of revelation[31]), that it follows that all subsequent Written Torah (and Oral Torah) is the result of an “Ongoing Revelation”—by people.

As Rabbi Steven Gotlib describes it (Jewish Action, Spring 2023) in his review of The Revelation at Sinai: What Does “Torah from Heaven” Mean? (eds. Yoram Hazony, Gil Student, and Alex Sztuden, Ktav, 2021):

collected comments on the Haggadah, suggests that the experience of slavery in Egypt was designed to instill this exact notion:

. . . A concern is raised throughout the book: a small, yet increasingly influential, group of scholars and theologians suggests that the Written Torah is the result of human development over time, rather than a literal, or at least objectively witnessed, Divine revelation. Such views—generally referred to under the heading of “ongoing revelation”—require no Moshe, no Mount Sinai, no revelation, no unique Jewish experience, and not even Hashem. Yet its proponents claim this to be an authentically Jewish view.

Gotlib notes there how Rabbi Gil Student (and Hazony) emphasize that full acceptance of Biblical criticism, including the idea of “ongoing revelation” as applied to the text of the Torah, undermines the entire Jewish project. Or in Gotlib’s review (“Theologically Speaking: God, Language, and the Maggid of Mezritsh”), Lehrhaus, April 25, 2022) of Ariel Mayse’s Speaking Infinities: God and Language in the Teachings of Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezritsh[32], he writes:

The primary question nowadays, though, is if such a revelation actually requires a literal voice of God to be revealed or not once contemporary biblical scholarship is taken into account.

Ultimately, Neil Gilman puts it starkly this way, “The only genuine diving line among contemporary Jews is verbal revelation, and on this issue one can only be for or against”[33]

The discussion and argument—for and against—by contemporary thinkers as Yehudah Gellman[34], Tamar Ross[35], and Marc Shapiro[36] continues in a proliferation too extensive to catalog. And in the context of “ongoing revelation,” A. Mayse even proposes[37] that R. Dov Ber, the Magid of Mezeritz, passed the understanding of “revelation as an unfolding process in which the ineffable divine is continuously translated into human language” onto several early Hasidic masters including “Menaḥem Naḥum of Chernobil, Ze’ev Wolf of Zhitomir, and Levi Yitsḥak of Barditshev” [38] as it appears in their works. However, the idea of “Ongoing Revelation” does not necessitate a theory of (or belief in) “Inaudible Revelation” at Sinai, and certainly not by Hasidic Masters. In some examples of this, the attribution of the connection to “early Hasidic masters” is demonstrably false.

R. Shneor Zalman of Liadi[39], for instance, forcefully articulates the idea that innovation and discovery as “Ongoing Revelation” in Torah is both a mystical[40] and halakhic religious obligation[41]. Yet he also asserts clearly that the revelation at Sinai was unambiguously audible and that all Positive and Negative commandments were contained in the first two Commandments, “since only these we heard, since they contain the entire Torah.”[42] Moreover, this of itself obligates every Jew to delve and reveal the Torah embedded in it, and at every level implanted there. (This is besides the obvious that the Siddur he compiled has in it Lecha Dodi’s “‘Observe’ and ‘Remember’ in one utterance/the One and Only God allowed us to hear.”)

All this might reflect Hazal’s formulation,[43] “Even what a proficient student in the future will innovate was said to Moses at Sinai”, the space and necessity of innovation (as “ongoing revelation”) which is yet grounded in the revelation at Sinai. It refers to what was imparted in the 40-day period after the verbal revelation on Shavuot.[44] And all subsequent Torah was embedded in that taught in the 40 days on Sinai: Shemot Rabah 41:6, “Did Moshe learn the entire Torah . . . in 40 days? Rather The Holy One Blessed Be He taught Moshe general principles.” But according to R. Shneor Zalman, as he articulates, all the Torah taught in those subsequent 40 days was embedded already in the Ten Commandments themselves, or perhaps even in the first two Commandments.

Fascinatingly, in that relationship, in a hybridized reading, James A. Diamond (“The Cherubim: From Guardians of Eden to Auschwitz”[45], in fact notes how in the rabbis even imagining God appearing at Sinai in the mode of “a teacher teaching Torah” [Tanhuma (Buber) Yitro 16], they thus situate themselves “as God’s successors in the continuous unfolding of that foundational revelation.” And he notes: “The rabbinic interpretive enterprise assumes that very posture, offering continuing access to God’s revelation, itself metaphorized as a ‘tree of life’ (e.g. bBerakhot 32b on Prov 3:18) whose original is no longer audible except through the medium of rabbinic teaching.”

Conclusion

This note on revelation started with blintzes. We have seen the significance and relevance of its possibly unsuspected bearing on the issue of the revelation at Sinai. In the case of this Minhag Yisrael, we might say that literally, “Minhag Yisrael Torah Hu” (“The custom of Israel—is Torah”) or “Minhag Avoteinu Torah Hu”[46], in the way it comes to embody or reflect the experience of the revelation of the Torah at Sinai itself.

As such, in that experience we find ourselves back in the heder at Sinai, hearing a very sonorous and quite audible “Qamatz Aleph A”, with all of the Torah embedded in it to be revealed. In that trajectory we return perforce to the originary “Qamatz Aleph A” heard there. Thus on Shavuot we re-experience the concrete metaphor of Israel’s communal Hakhnasah Le-Heder’s milk-and-honey cake’s sweet Aleph and its other letters at Sinai. And we appropriately enjoy the sweetness of receiving the Torah again anew, from Aleph.

[1] R. Gedalia Oberlander, Kovetz Or Yisrael, 32:104-120, and updated in his Minhag Avoteinu Be-Yadeinu; Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisrael, vol. 3 (Jerusalem: Mossad Ha-Rav Kook, 1994), 139.

[2] R. Eliezer Brodt, “The Mysteries of Milchigs,” Ami Magazine (June 10, 2013), cites, among others: R. Pinchas Schwartz, Minhah Hadashah, 38-44; R. Shariah Deblitski, Kuntres Ha-Moadim, 37-40; Kovetz Etz Hayyim (Bobov) 6 (2008), 239-242; Pardes Eliezer, 227-316; R. Tuviah Freund, Moadim Le-Simhah 6, 490-505; R. Yitzchak Tessler, Peninei Minhag, 292-319; Yehudah Avidah, Yiddishe Maholim, 43-44; M. Kosover, Yiddishe Maholim, 75, 77, 98; etc.

[3] Similarly, Aton Holzer writes in “Blessed Are the Cheesemakers: In Search of Ancient Roots of Dairy on Shavuot,” Hakirah 30 (Summer 2021): “There is not a single mention of the practice in the Rabbinic corpus that precedes medieval Ashkenaz—not in Mishnah, Midrash, Talmud Bavli, Yerushalmi, piyyut or Genizah fragments.”

[4] His student R. Mordekhai b. Hillel reports (Shabbat no. 369) that R. Meir was asked why it is permissible for the child to eat the Aleph Beit letters, thus erasing them on Yom Tov (that is: Shavuot [Hida, Mahzik Berakhah, I:340]).

[5] Shir Ha-Shirim Rabbah 4: “Anyone who speaks words of Torah in public and they are not pleasant to their listeners like this honey and milk that are intermingled, it would have been preferable for him had he not said them… Even one who reads a verse in its pleasantness and in its melody, the verse says in his regard: ‘Honey and milk are under your tongue.’” See also Devarim Rabbah 7:3: “That the Torah is compared… to honey and milk… what is the source? ‘Honey and milk are under your tongue.’”

[6] See also President George H. W. Bush’s acceptance speech in 1998 for the Republican Party’s nomination for president: “I believe in another tradition that is, by now, embedded in the national soul. It’s that learning is good in and of itself. You know, the mothers of the Jewish ghettos of the East would pour honey on a book so the children would know that learning is sweet. And the parents who settled hungry Kansas would take their children in from the fields when a teacher came. That is our history.”

[7] See also Shlomo Bar of Ha-Breirah Ha-Tivit’s bitter protest, “Etzlenu Be-Kefar Todra,” against Moroccan Jewish culture’s erasure: In our community of Kefar Todra, when the celebrant reaches the age of five, we bring him to the synagogue and write all of the letters from aleph to tav with honey on a wooden tablet—and the Torah that is in the mouth is as sweet as the taste of honey.

[8] See Rema and Turei Zahav, Yoreh Deah 245:8.

[9] Sometimes this occurs not at the age of three but instead at the age of five or later, or it occurs at the first upsherin haircut at age three.

[10] In the context of material culture, Israeli field teacher Netanel Elinson (“Siyyur Im Netanel Elinson Le-Sadot Beit Lehem Megaleh Mah Karah Be-Emet Be-Megillat Rut,” Makor Rishon, May 25, 2023) notes that while in Israel in late spring at the time of Shavuot, goats and cattle didn’t produce a high volume of milk (Aton Holzer notes it was certainly more scarce after Hazal forbade raising goats there). The custom emerged in the medieval Rhineland where milk was plentiful at that time. (See Jeffrey L. Singman’s Daily Life in Medieval Europe [Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1999], where he explains that spring and summer were times of calving in medieval Europe—when calves were weaned and fodder was plentiful—so there was an abundance of dairy products then; see also John Cooper’s Eat and Be Satisfied: A Social History of Jewish Food [Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1993] on the abundance of milk at this time of year). Elinson suggests that wheat would be more appropriate for Shavuot in Israel (as reflected in Megillat Ruth). However, I note how the dairy custom’s universality in and outside of Israel by Ashkenazim and Sephardim simply reflects how all Shavuot customs developed over centuries outside of Israel (Rashi, Pesahim 68b: “to show that this day is pleasant and accepted to Israel because the Torah was given on it”) over two days, compressed today in Israel into one: Tikkun Leil Shavuot, Akdamut, Megillat Ruth, Yetziv Pitgam, R. Yisrael Najara’s Ketubah, Yizkor, Azharot, and blintzes. Rema (also Magen Avraham) I:494 does suggest that Shavuot’s milchigs commemorates the shetei ha-lehem’s two Shavuot wheat loaves (Pri Hadash [ad loc.] dismisses this as forced).

[11] Sefer HaSihot 5703 (1943), 147.

[12] The reference to “600,000” may allude to the idea of “‘Israel (y-s-r-’-l)’ is a contraction for ‘there are six hundred thousand letters in the Torah (yesh shishim ribo ‘otiyot latorah)’” (Zohar Hadash, Shir HaShirim 74d; Megaleh Amukot, Ofen 186), to imply here that the Torah’s text received at Sinai mirrored the communal peoplehood of Israel who received it.

[13] Old Worlds, New Mirrors: On Jewish Mysticism and Twentieth-Century Thought: University of Pennsylvania Press 2012.

[14] Idel is Eastern European; Scholem was not.

[15] “Wellhausen and the Hasidim,” Modern Judaism 26 (2006).

[16] Benjamin D. Sommer, Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015);

[17] “What Did the Rymanover Really Say About the Aleph of Anokhi?,” Kabbalah 34 (2016) (Hebrew).

[18] And Sifrei Bamidbar 102; Tanhuma Yitro 11; Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer 11.

[19] In the Decalogue’s two versions.

[20] Hizkuni, Shemot 20:13; Shulhan Aruch HaRav I: 494, 8-11: “On Shavuos it is customary to read [the Ten Commandments] communally… to read each commandment as a single verse, [even when the commandment contains several verses or only part of a verse. The rationale is that since] the Ten Commandments were given on that day, we read them in the same manner they were given, each commandment constituting a distinct verse” (translation from Chabad.org)

[21] De Deca Logo; De Specialibus Legibus.

[22] Bereishit Rabati, Bereishit, 3.

[23] Vaethanan, 184.

[24] “Azharot” are ancient poetic lists of the 613 Mitzvot which Sephardim say appropriately on Shavuot.

[25] R. Shneor Zalman was an adherent of the Shelah before becoming a disciple of the Mezeritcher Magid.

[26] R. Yaakov Yosef of Polnoya, Ben Porat Yosef, Noach

[27] Likutei Amarim 158; Or Torah, Pinhas.

[28] Connection to J.L. Borges’ story of a physical Aleph point containing all the universe (The Aleph and Other Stories, 1949) is only in how his poem about the Maharal’s Golem cites Scholem, as he admitted it rhymes with ‘Golem.’

[29] Benjamin D. Sommer, Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015); Neil Gillman, Sacred Fragments: Recovering Theology for the Modern Jew (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1992)

[30] “The primary content of revelation is revelation itself. ‘He came down’ [on Sinai] this already concludes the revelation; ‘He spoke’ is the beginning of interpretation”, The Star of Redemption.

[31] Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York, 1955), 185. Heschel’s own position on non-verbal revelation and “ongoing revelation” has been characterized as deliberately elusive and ambiguous. See, Arnold Eisen, “Re-reading Heschel on the Commandments”, Modern Judaism, 9:1 (1989); Elliot Dorff, Conservative Judaism: Our Ancestors to Our Descendants, (2007), Neil Gillman, “Toward a Theology for Conservative Jews”, Conservative Judaism 37:1 (1983).

[32] Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020

[33] “Toward a Theology for Conservative Jews”, 8

[34] “Realism and Constructivism: A Correspondence between Professors Yehuda Gellman and Tamar Ross”, Association for the Philosophy of Judaism.

[35] “Behind Every Revelation Lurks an Interpretation: Revisiting “The Revelation at Sinai”, Lehrhaus, May 2023.

[36] “Confronting Biblical Criticism: A Review Essay” Lehrhaus, January, 2023.

[37] Ariel Mayse, “The Voices of Moses: Theologies of Revelation in an Early Hasidic Circle,” Harvard Theological Review 112, no. 1 (January 2019): 101–125.

[38] The only connection of the Berditchiver to any of this would be his famously suggested reason for the custom of milchigs on Shavuot (cited in Toldos Yitzchak,1868), noted in the Mishneh Berurah as heard “in the name of a great scholar.”

[39] Mayse, “The Voices of Moses,” does aver: “Shneur Zalman’s highly-intellectualized reading of Sinai as paving the way for cerebral communion with the divine both complements and challenges other voices in the Maggid’s circle.”

[40] Tanya, Igeret HaKodesh 26.

[41] Hilchot Talmud Torah 1:4; 2:2.

[42] Likutei Amarim 20.

[43] “Ve-afilu ma she-talmid vatik atid lehadesh kulan ne’emru le-Moshe be-Sinai” is the text as it appears in Margoliot Vayikra Rabah 25 from a manuscript. See also Bavli Megilah 19b; Yerushalmi Peah 2:4, Shemot Rabah 47, Kohelet Rabah 1:9; 5:8.

[44] See Aryeh Leibowitz, “Matan Torah: What was Revealed to Moses at Sinai?”, Hakirah 32:2022.

[45] Marginalia, January 20, 2023)

[46] Sefer Rokeach describes this custom as “minhag avoteinu,” “a practice of our forefathers.” The expressions, “Minhag Yisrael Torah Hu” or “Minhag Avoteinu Torah Hu”, emerge at this same time: Shmuel Ashkenazi, Alfa Beita Tinyeta di-Shemuel Zeira (Jerusalem, 2011), 2:576, attributes its earliest source to Rabbenu Tam. See also, Israel M. Ta-Shma, Minhag Ashkenaz ha-Kadmon (Jerusalem, 1992), 27ff, 104-5. In Mahzor Vitry of Rashi’s disciple, R. Simhah, (378, 506) and Tosafot to Menahot 20b (attributed to the school of Rabbenu Tam)): “u-minhag Avoteinu Torah Hi” . According to Haym Soloveitchik, “Minhag Ashkenaz ha-Kadmon”, Collected Essays II, 49, “Minhag Avoteinu Torah” or “Minhag Torah Hi” was likely coined by Rabbenu Yitshak b. Yehudah, a student of Rabbenu Gershom and the teacher of Rashi.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.