Ilan Fuchs

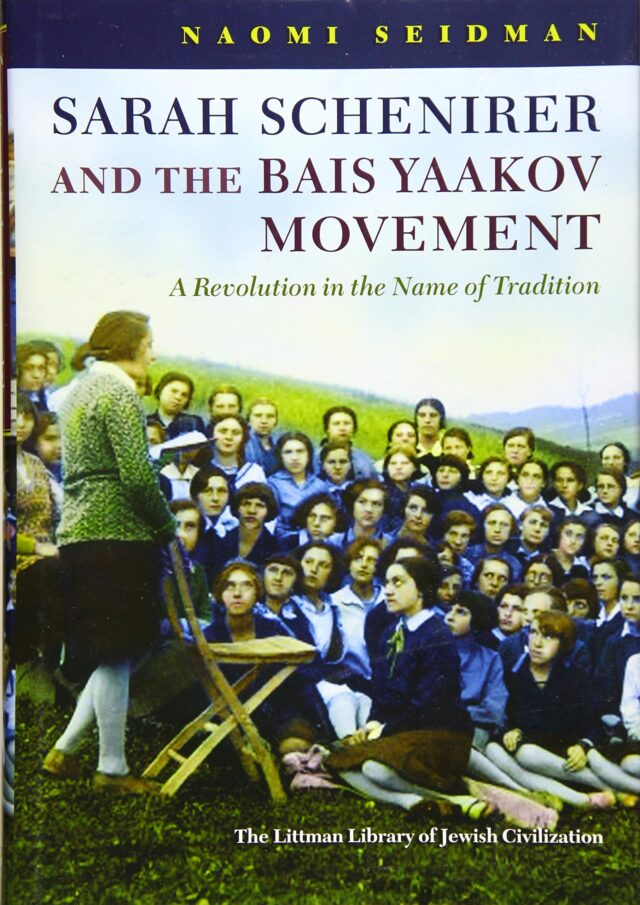

Book Review of Naomi Seidman, Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2019)

Naomi Seidman’s book fills a void in the study of modern Jewish history. No one doubts the centrality of Sarah Schenirer’s work in the evolution of Orthodoxy in the twentieth century. Yet, for decades there has been no scholarly interest in telling the story of the establishment of the largest educational movement in interior Poland. Perhaps because of the lack of access to archives, or because of the need to explore Jewish and Polish primary sources, the important story of Sarah Schenirer was left to hagiographies and memoirs of others who were involved in the inception of the movement.

Seidman’s book relies on primary sources of different kinds: memoirs, the monthly Bais Yaakov Journal (the journal published by the movement in Poland and its namesake in Lithuania), Yiddish newspapers, and other archival materials. She was also given access to Sarah Schenirer’s diary―originally written in Polish―which has recently resurfaced and is scheduled for publication in the near future.

The volume focuses on two distinct trajectories. The first follows Schenirer and tracks her role in founding the Bais Yaakov movement. The second is Bais Yaakov’s growth in the interwar period, once the reigns of the movement had passed to men who further expanded its reach. The book’s main thesis centers on the idea of traditional revolutionaries. Sarah Schenirer was no doubt a revolutionary: she changed the status of women in the religious Jewish world and reshaped societal expectations about women’s religiosity. Nevertheless, she promoted this revolution in the name of tradition.

Along those lines, the book examines the extent to which the Bais Yaakov movement could be considered revolutionary in the context of its times and whether and how it eventually lost this revolutionary fervor. In other words, the book analyzes how Schenirer broke gender boundaries by assuming leadership positions and how men took over the movement afterward. Furthermore, Seidman’s book highlights the religious and social forces that both influenced and were influenced by the nature of Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov―namely: Hasidism, Neo-Orthodoxy, Yiddishism, and even socialism.

In her own personal life, Schenirer broke traditional gender boundaries. The first example was evident from a young age with her pious behavior winning her the title ‘Little Miss Hasid’ [husidke] (55). The early Bais Yaakov movement was highly influenced by the model of leadership found in the Hasidic courts that dominated Poland. The relationship between students and Schenirer was similar to the relationship between a hasid and a rebbe. Like a hasidic rebbe, she was revered by students (they called her “Sarah Imeinu,” and Schenirer was approached with similar mannerisms to those seen in the hasidic courts, such as asking for blessings). This rare example of a female religious leader at the center of an exclusively female religious community exemplifies the novelty of the movement and the charismatic character of Schenirer herself.

Sarah Schenirer’s spiritual sources of influence were not limited only to Eastern Europe. She also broke cultural boundaries by being deeply influenced by German Neo-Orthodoxy (47-48). Schenirer credited the inspiration for her public endeavor to the teachings of Neo-Orthodox rabbis from Vienna, where she lived during the first World War. Schenirer introduced the writings of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch to the curriculum of Bais Yaakov, and she offered a general studies curriculum alongside traditional Jewish subjects that had previously not been formally offered to young women and girls. She also engaged with Western culture more broadly, and she was interested in its different facets, primarily literature (194). This orientation filtered through to the Bais Yaakov Journal.

The book demonstrates how the model of Bais Yaakov was designed to create a new image of Jewish women, a model of feminine spirituality that did not exist before. The Jewish woman of the interwar period―as envisaged by Schenirer―possessed a strong religious identity that involved engagement with religiosity and textual study (though not Talmud) and actively modeled meticulous religious observance. Furthermore, the Jewish woman of Schenirer’s imagination also engaged with Western culture (albeit critically) and promoted a political and artistic agenda that was wholly Orthdox and served as an alternative to Western politics and culture.

Undoubtedly exemplifying the traditional revolutionary, she was able to maintain Orthodox boundaries and at the same time change gender roles and foster active spiritual development among women. She created a discourse that focused on women as mothers and their responsibility to educate the future generations. At the same time, she sought to develop a curriculum that allowed women to maintain a Jewish identity while working full time to help support their families, as was generally the case during this period.

In this way, the Bais Yaakov movement attempted to deal with the economic reality of Jews in Eastern Europe, which demanded that women work outside their homes to sustain their families (132). The interwar period saw a significant decline in the economic condition of Polish Jewry. As Ezra Mendelsohn writes, this was “not a process of proletarization but of pauperization.”[1] Jews joined the ranks of light industry (such as the garment industry), barely making a living in light of the global recession and economic persecution orchestrated by the Polish government and also due to popular antisemitism that limited Jews’ ability to enter heavy industry. In this reality, women often searched for work outside of the Jewish community. The difficulties of maintaining a Jewish identity while making a living outside the boundaries of the Jewish home and community demanded active Jewish identity building and a narrative that could withstand the interaction with the non-Jewish world. Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov addressed this blended reality through its orientation to both Jewish knowledge and ideas as well as Western politics and culture.

The Bais Yaakov revolution was a traditionalist revolution making a call to revitalize Orthodoxy, not to break it. But, Naomi Seidman also points to the fact that even during Schenirer’s lifetime, the tension between tradition and gender roles was evident and even limited Schenirer’s role in the movement she founded. During the 1920s, prominent men took over leading roles in the movement and made decisions on the future of the entire chain of schools. Agudas Yisroel’s support for Bais Yaakov factored into its success, but it also signaled a shift from Bais Yaakov as a grassroots, female-led initiative, to an institutional, male-dominated endeavor. Rabbis like Alexander Zusha Friedman and Yehudah Leib Orlean took positions of leadership, rather than the women who studied and advanced through teaching seminaries and the institution itself. A striking example from the life of Schenirer, which Seidman analyzes in depth in the book, has to do with Schenirer’s refusal to speak publicly in front of men at Bais Yaakov events. In the internal literature and the autobiographies of students, this action is interpreted as a choice Schenirer made out of modesty considerations. In contrast, Seidman suggests that the episode is a primary example of the “routinization” of the movement and its ideals. Seidman here is referring to the Weberian concept of the “routinization of charisma.”[2] Weber’s model of charismatic authority comes about as a result of a charismatic person who is treated by his disciples as exceptional. In this case, Schenirer was a charismatic leader. Her legitimacy was derived from spiritual qualities, not traditional or legal sources of authority. However, after the death of the charismatic individual, the leadership becomes routinized; the next generation of leaders in the movement will function based on law or tradition rather than personal charisma.

This shift clearly took place within the Bais Yaakov movement. Schenirer was pushed aside to one degree or another when Leo Dutchlander and later Yehudah Leib Orlean assumed leadership of the day-to-day running of the movement. As the prime example, Seidman discusses an event held on September 13, 1927 in the cornerstone ceremony for the new Krakow seminary (75). Schenirer did not sit on the dais with the dignitaries that were all men. Instead, she was sitting with her students in the audience, as she shunned public attention and preferred to modestly not be the center of attention. Seidman sees this event and the reaction to it in the press reports as a representation of the dual strands within the movement: the charismatic leadership of the revolutionary Schenirer and the routinization of the movement by the all-male agudah establishment. Seidman hints at these dynamics in post-war Bais Yaakov schools as well. Indeed, the role of male leaders in all-girls schools in the Haredi world and in Modern Orthodoxy today―and the complicated gender and institutional dynamics it engenders―is certainly a topic for future research.

This book changes the field of the study of Orthodoxy. No more can one portray interwar Orthodoxy as a monolithic and homogeneous entity. Orthodoxy was a spectrum: Beis Yaakov included students and teachers that were interested in socialism (171, 181) and Zionism (178-179), and it also promoted concepts of Jewish religious art (182-183). The cultural references in the Bais Yaakov Journal were not exclusively Jewish and spoke to a worldly readership that was engaged in self-reflection and intellectual growth. The journal showed the interest of students in social justice and the ideas of communal property and responsibility to the poor (181). Indeed, as Seidman demonstrates, several Bais Yaakov educators were linked to the socialist movement. Furthermore, the journal’s political discourse also included discussions about Zionism and the role of Orthodoxy in the emerging Yishuv (community of Jews in pre-State Israel). The journal also attempted to promote literary work by women. Even though most of the published poems and short stories were of novices, they ascribed to a vision of Orthodox art that presented an alternative to contemporary aesthetics and offered a theologically informed body of literature.

The book outlines its arguments for seeing Bais Yaakov as a traditional revolution in a convincing manner. In the first years of the movement in Poland, the Beis Yakov sphere was home to many views and ideas: socialism, conservatism, feminism, traditionalism, Zionism etc. All these ideas were coexisting within a spectrum that allowed women to experiment, attempting to create a new model of Jewish feminine identity. This experiment with a more revolutionary Bais Yaakov was unfortunately cut short by the Holocaust.

The foundation laid by Seidman will be useful in further research. Perhaps most significant is the second half of the book where she translates the collected works of Schenirer into English. This first translation will allow further evaluation of Schenirer, a project that should take place with the anticipated publication of her diary from 1910 to 1913. Seidman showed she was married twice and pointed to the emotional toll the divorce from her first husband took on her. These facts, together with the recently surfaced diary, might possibly allow another vantage point on her personal motivations in the establishment of the Bais Yaakov movement. The translation of the collected works will enable a deeper appreciation of Schenirer’s path.

The book also creates space for more scholarship on interwar Orthodoxy and the complex relationship between different factions within Agudat Yisrael. Seidman aptly shows that the Agudah world itself was a spectrum. Within Agudah, there were not only rabbinical leaders but also intellectuals who promoted greater involvement in the world, both in the political arena and in the cultural realm. They suggested that the Torah can inform more parts of modern life, and they wanted to shape an Orthodox community in the modern context (both in the diaspora and in the new Yishuv). This book is a building block in the future research of Orthodoxy and opens new frontiers for scholarship that will surely follow.

[1] Ezra Mendelsohn, The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 2001), 25.

[2] Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, trans. A. M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons (New York: The Free Press, 1947), 358-373.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-100x75.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.