Howard Apfel

Orthodox physicians occasionally grapple with complex bio-ethical problems in areas rarely encountered by individuals in other professions. End-of-life decisions, organ transplantation, abortion, and precise determination of the time of death are just a few of numerous well-known issues confronted by physicians in the related subspecialties. Many relevant books and articles have been written on these topics, and various rabbinical and medical experts have weighed in on the various halakhic aspects of these high-profile issues. Most concerned physicians are at least familiar with the opinions offered and the topics have engendered considerable discussion at forums and conferences.

Afforded far less hype, but actually far more common, are the many day-to-day halakhic concerns that an Orthodox physician must navigate from the moment they choose to become a healthcare provider. Spanning all four sections of the Shulhan Arukh, most of these seemingly simpler halakhic questions arise at the time of medical school and residency training, when individuals have the least control over their professional responsibilities and daily schedules. Situations that require varying degrees of hillul Shabbat are especially common, and at times are difficult to resolve properly. As a consequence of the complexities of hilkhot Shabbat, patient care demands, and the ever-changing modern medical technologies, even well-intending adherents often find themselves inadequately prepared for those, as well as many other unexpected halakhic complications that arise. Unfortunately, at times, this may lead to unintentional laxity or even apathy in observance.

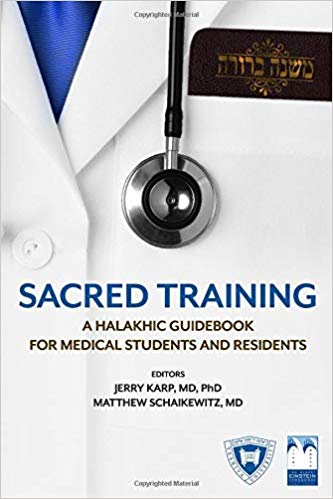

For this reason, the recently published halakhic guidebook, Sacred Training, edited by Dr. Jerry Karp and Dr. Matthew Schaikewitz, provides a critical and invaluable resource in the education of health care professionals concerned with strict adherence to Halakhah. Written and edited by insiders (i.e. physicians and medical students themselves), it effectively covers most of the problems regularly encountered. The work is organized chronologically around a doctor’s career, beginning with the preclinical years, to clinical training in medical school, followed by residency, fellowship, and beyond. The potential concern of not having a rabbinic co-author to this work is overridden by the extensive, thorough, and erudite research put into each section of the book, as well as the fact that multiple rabbinic authorities reviewed the book and offered feedback prior to its publication. Moreover, at the end of each section, when multiple possible conclusions are drawn, the reader is encouraged to involve one’s own personal rabbinic advisor for practical applications.

The common denominator to almost all of the topics selected for discussion is that they emerged from the actual experiences of the authors themselves during their years in school and training. Each topic is itself organized in a manner conducive to mastery of the practical Halakhah. The practical contemporary halakhic concern is described and introduced, a discussion of the general halakhic background is then offered, and this analysis is followed by the halakhic conclusions of contemporary authorities. All sources cited are carefully and thoroughly footnoted.

The scope of topics covered includes often underemphasized areas such as patient dignity, tzniyut, moment of death, and care of the deceased. There is also an entire chapter dedicated to navigating the specific customs and prohibitions of the mourning periods on the Jewish calendar. Because many of these particular topics are less precisely defined by the halakhic codes and responsa literature, they lend themselves to widely varying rabbinic approaches even within the Orthodox community. It is therefore not surprising that the conclusions drawn are less clear cut, provide fewer background sources, and exhibit less definitive halakhic decisions, in comparison to other halakhic topis. However, rather than ignoring these important and halakhically relevant areas altogether, the book offers useful general advice and specific pragmatic approaches to managing these challenges. For example, in the section on tzniyut, creative practical suggestions for maximizing modesty while maintaining the strict sterile standards of the operating room are offered. In the chapter on care of the deceased, a thorough, step by step guide to dealing with this difficult set of circumstances is outlined. The chapter pragmatically addresses a broad number of halakhic procedural issues while maintaining an appropriate sensitivity to the deceased patient’s family. It also effectively covers the hospital/legal requirements and in general covers many details that inexperienced, non-hevrah kadisha members would be insufficiently prepared to manage. Finally, in the chapter on mourning periods, the halakhot of Tishah Be-Av are discussed more extensively. Possible lenient approaches are then suggested for dealing with easily neglected issues such as hand washing with soap or sanitizer, greeting patients, sitting on a chair or bed, and studying for an exam.

In addition to those sporadically occurring challenges, the book discusses at length other issues, more frequently encountered but at potentially even greater risk for neglect. These include morning rituals after being up all night, reciting berakhot and davening in a hospital setting, and the earliest time for davening, tallit, and tefillin. As these topics relate to many mekorot, much background and overview is offered before these principles are applied to practical situations. For example, in the section dealing with the halakhic implications of staying up all night, the chapter first elucidates in detail the relevant halakhic sources defining different levels of sleep. It then painstakingly goes through specific halakhic ramifications such as ritual hand washing, birkat ha-torah, and other birkhot ha-shahar. Mindful of the complexity of the topic, the author concludes the chapter with a practical summary of the various relevant scenarios.

In addition to male specific issues such as tallit and tefillin, other topics that pertain uniquely to women are also elucidated. These topics are of particular contemporary interest as more and more women, including many observant ones, have been entering the medical profession. Thus, in addition to the recommendations related to tzniyut discussed above, mikveh issues and prayer obligations for women are both elaborated upon extensively. All of these sections were written by halakhically knowledgeable women pursuing careers in medicine, granting the reader again the functional advantage of an emphasis on the practical related concerns they experienced directly.

A potential drawback for any multi-authored work is a lack of uniform writing style to the independently written chapters of the book. In addition, when there is considerable disparity to the amount of available sources for different topics, attaining an even degree of thoroughness for each topic is difficult. Overall, the Sacred Training editors were successful in maintaining a fairly consistent style of presentation, allowing for a comfortable flow across chapters for the reader. However, while most of the authors are to be commended for adequate coverage of their particular topics, some chapters appear far more thorough than others. As noted, this may have been related largely to the nature of the particular topic under discussion. For example, there is obviously far more basic source material and practical content to discuss in the chapters dealing with hilkhot Shabbat and staying awake all night, than for maintaining patient dignity or physical contact between men and women. Nevertheless, one particular chapter written by Dr. Karp within the section on “Residency and Shabbat” deserves special mention for its meticulousness. The breadth and depth of the discussion regarding residency programs and Shabbat accommodation is the most extensive discussion of this issue currently available. It exhaustively explores all of the divergent opinions related to this complex and at times contentious issue, encompassing all possible halakhic and hashkafic vantage points. For this reviewer it was a particularly fascinating read, as I have a long-time particular interest in this critical and complex area. I have spent considerable time studying many of the sources myself and have discussed them extensively with many notable poskim. Dr. Karp’s presentation not only added significantly to my knowledge base of the halakhic issues involved, but his inclusion of many relevant meta-halakhic considerations enhanced my hashkafic perspective as well. There is no doubt that this chapter can serve as a valuable resource for rabbanim involved in guiding Shabbat-observant medical school students towards optimizing their residency choices.

Sadly, however, the entire section is likely only of academic interest (if even that) for the majority of readers of this guidebook. The current reality is that shomer Shabbat residencies are difficult to come by and Shabbat-friendly fellowships almost nonexistent. While it is the personal opinion of this reviewer that Shabbat-friendly programs are still the preferred option when available, realistically the vast majority of physicians in training will inevitably be faced with rotations and occasional on-calls that will require them to be in the hospital on Shabbat. This likelihood mandates that the halakhically concerned trainee maximize preparedness for those eventualities. More than an erudite discussion of the hypothetical requirements or advantages of Shabbat accommodation programs, most readers today will no doubt prefer (and expect) a more practical hilkhot Shabbat discussion, including direct advice on handling the many challenges they will face as physicians on call. Fortunately, Dr. Karp did not disappoint in this regard either. The remaining chapters of this section raise most of the relevant concerns and propose multiple acceptable solutions. As noted, the area of practical hilkhot Shabbat is particularly complex, yet the background discussion is presented in a clear, organized, and systematic fashion before applying the halakhic analysis practically to many of the common situations that arise.

One final advisory is that the majority of the work’s overall thoroughness, one of its greatest strengths, may also be its biggest drawback. Often, observant physicians and medical students encounter halakhic dilemmas without much warning or anticipation. I would therefore caution the reader that they will not find in Sacred Training an on the spot, quick reference guidebook analogous to the medical handbooks housestaff commonly use for urgent medical decisions while on call. Sifting through a lengthy chapter in order to decipher specific halakhic guidance needed at that very moment may be cumbersome and unappealing. For that reason, I would highly recommend that this book be studied in depth, well in advance of any specific situations that may arise. This will enable the reader to become fully familiar with its details and be able to ask a rabbinic consultant of their choice the relevant questions in order to best prepare for all halakhic eventualities.

In The Lonely Man of Faith (pp. 52-53), Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik celebrated the preeminent place that health care professionals occupy in the dignity aspiring, “majestic” world of “Adam the First.” By eliminating human pain and suffering, and the occasional conquest of death itself, physicians are able to realize for themselves a divinely sanctioned and deeply honorable existence. Undoubtedly, this positive depiction of physicians overall is well-deserved. Still, from the Rav’s perspective, observant Jewish practitioners have an additional basis for admiration, one that goes even beyond the “majestic” existence of Adam I. Through consistent vigilance and staunch commitment to halakhic observance, despite the many challenges, the Orthodox physician can attain the more venerated “cathartic, redemptive” existence so avidly sought out by Adam II. The careful study of available resources such as Sacred Training is an excellent first step towards achievement of this most sacred goal.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.