Ariel Clark Silver

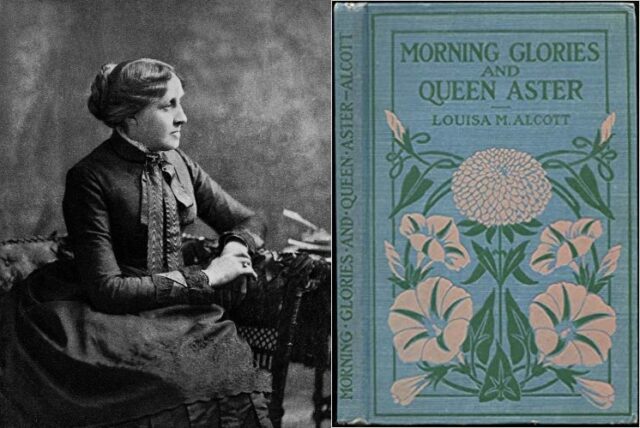

Purim arrives at the end of winter and the advent of spring. Perhaps, then, it will come as no surprise that the literary language of flowers was invoked in nineteenth century America to celebrate the significance of Queen Esther and her annual commemoration of deliverance through the female. Just a few years before the Botanical Society of America was formally established in 1893, Louisa May Alcott published her short tale, “Queen Aster,” about a well-positioned flower that grows both within and without the walls beside the road. Aster, a Greek name meaning star, alludes to the goddess Ishtar, a Babylonian variant of the female Canaanite deity, Asherah, from which the name Esther may be derived. And just like Esther, whose Jewish name, Hadassah, is forsaken in exile in favor of the Persian variant, Esther, the floral Aster also has a history of multiple identities. Though Aster is the traditional genus name for a flower in the Astereae tribe, the Aster often hides behind other names: Symphyotrichum, Ionactis, Eurybia, and Doellingeria. In America, she also lives in exile; only one species of Aster, otherwise native to Eurasia, originates west of the Atlantic.

In Alcott’s story, the lovely and determined Aster functions as an Esther figure, leading a revolt against the prideful Golden-rods who have perennially ruled the kingdom of the meadow from their privileged place within its walls. The roadside asters, privy to the “great world” beyond the meadow, convey their information and insight to their relatives inside the court. Already we see a dynamic developing much like that in the Book of Esther between Mordecai, who lives by the side of the road, and Esther, who is ensconced in the palace of the Persian king, Ahasuerus. In “Queen Aster,” one of these roadside asters finally speaks up: “Matters are not going well in the meadow; for the Golden-rods rule, and they care only for money and power, as their name shows. Now, we are descended from the stars, and are both wise and good … it is but fair that we should take our turn at governing … I propose our stately cousin, Violet Aster, for queen this year.” This plea draws not only the Asters, but the Clovers, Buttercups, and the Pitcher-plant to their case, but other flowers – the Cardinals, Fringed Gentians, and Clematis – joined the Golden-rods in opposing the idea of displacing a king.

Read principally as a whimsical tale, or “Flower Fable,” which was its original 1887 title, this story by Alcott deserves greater consideration as a continuation of the critique which Hawthorne begins in “Legends of the Province House” (1837). Like “Legends,” which introduces Hawthorne’s first Esther figure, Esther Dudley, Alcott’s “Queen Aster” combines a re-consideration of both monarchy and male rule. Written a century after the signing of the United States Constitution, this tale suggests that while Americans may have overcome the sovereignty of England, they had yet to surmount the patriarchy seemingly implicit in any political rule. Many of the flowers in the meadow “blush with shame” and are “shocked” by the “bold” idea of a queen in place of a king. The very suggestion of female rule drives them to scorn, and her victory at the verdant ballot box causes them to react with anger, disdain, and dismissal: “We will never go to Court or notice her in any way.” Worse, they slander her as a “dreadful, unfeminine creature.” In their rage, they reject her authority and turn their backs on her, dividing the meadow. Her supporters, on the other hand, sustain her with their solidarity, much as the handmaidens in the story Esther fast with her as she prepares to challenge the conventions of monarchical male rule.

The cause of Queen Aster is immediately associated with liberty, justice, and deliverance. Echoing the primordial experience of Adam and Eve in the Book of Genesis even as she channels the existential threat faced by Esther, her first act upon ascending the throne is to banish the evil snakes who have lured innocent birds to death. Queen Aster makes quick work of Haman-like serpents who build nests (or gallows) of grief for others. She then proceeds to eradicate other forces of stupidity, laziness, greed, and dishonesty so that her flower people can thrive in peace and comfort, free from harm and threat of extinction. Her efforts are also benevolent, building hospitals for the sick and homeless, and altruistic, extending help to ladybugs who had lost their children and ants crippled in conflict. Her goodness and success in governance then lead to messages of “praise and good-will” from other rulers. Her reign is a Purim holiday writ large: choosing a new queen, executing a criminal, charitably giving gifts, and celebrating the triumph over forces of darkness and destruction.

The spirit of Purim pervades the story of “Queen Aster” and extends even to its final reversal, upending a palatial world once controlled by ignorance, fear, and prejudice. When the accomplishments of Aster become well-known, the reluctant Cardinals, Gentians, and Clematis, who resisted her administration, turn at last to embrace her rule. But it is the shift in Prince Golden-rod that is the most significant. In the Book of Esther, the Queen requests an audience with her husband, King Ahasuerus, risking death if he does not extend his golden scepter to her. Esther is able to advance her redemptive plans in great measure because she is admitted into his presence, where she can then convince him of her righteous cause. In Alcott’s tale, however, it is reversed: the displaced Prince Golden-rod is the supplicant to a woman on the throne. In the end, he admits that “she has done more than ever we did to make the kingdom beautiful and safe and happy, and I’ll be the first to own it, to thank her and offer my allegiance.” This remarkable subversion at the end of “Queen Aster,” where the male Prince effectively places himself, the golden rod (read: scepter), in the hands of the female Queen, acknowledging that she “is fitter to rule,” magnifies the trope of enthronement and dethronement at the heart of Purim. In “Queen Aster,” Alcott brings into bloom a new ideal made possible by the world imagined in the Book of Esther: the bending of both monarchy and male rule to the bright light of female wisdom and discernment. The last plea of Prince Golden-rod, to “let me help you if I can” as a friend and faithful subject, is answered by Queen Aster with a more egalitarian vision. She proposes that “there is room upon the throne for two: share it with me as King, and let us rule together.” Building on the advances made by Queen Esther, who was granted possession of up to half a kingdom by King Ahasuerus, Queen Aster suggests shared rule of a province no longer governed by patriarchy. In Alcott’s utopian vision of social unity through sustained matriarchal influence, enduring liberty requires not just the eradication of evil, but the establishment of justice and true equality.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.