Jeffrey Saks

A number of years ago, as I was making my unlikely entrée to the world of S.Y. Agnon’s Nobel Prize-winning Hebrew literature, I had a mid-life opportunity to audit a graduate seminar at the Hebrew University. We were studying Agnon’s magnum opus Temol Shilshom (translated as Only Yesterday), a novel set in Palestine in the decade before World War I, which tells the tragic tale of Yitzhak Kumer, a young émigré to Eretz Yisrael torn between secular Jaffa and pious Jerusalem. At some point, one of the students, a yeshiva boy who had left the beit midrash and transitioned to the lecture halls of Mount Scopus, asked me if I understood the novel. I assume he was asking me, as an American oleh with a pronounced accent, if I was able to follow the Agnonian Hebrew. With a combination of pride and hutzpah, I replied that not only did I understand it, but as the only immigrant in the room full of native-born Israelis, I may have been the only one in the seminar who did. My own life experiences helped me identify with the protagonist who “left his country and his homeland and his city and ascended to the Land of Israel to build it from its destruction and to be rebuilt by it.”

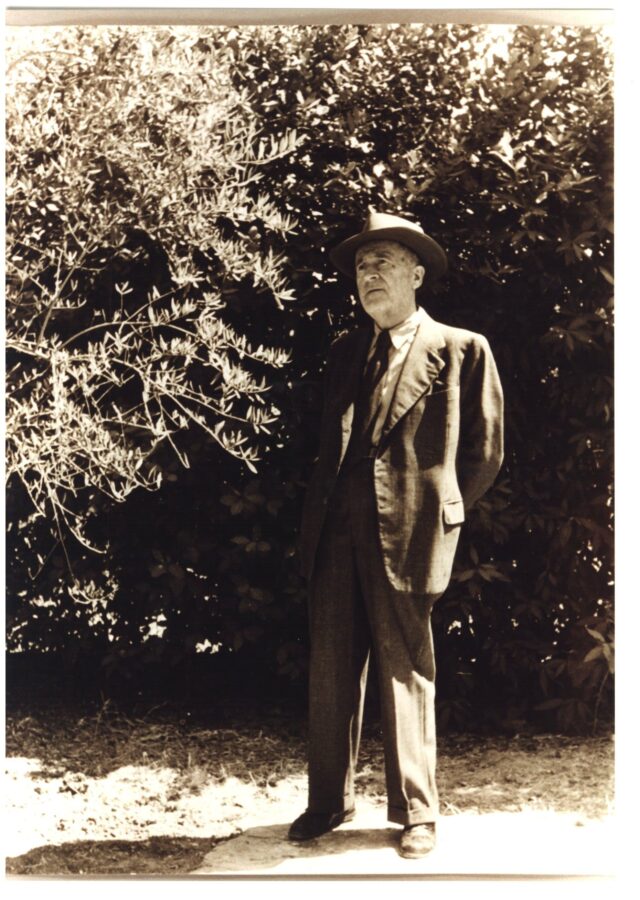

As we mark the fiftieth anniversary of Agnon’s death, I am reminded that an awareness that a sense of place, the tension between one’s origin and destination, runs throughout Agnon’s writing. This is present both when depicting individual characters, as well as when his stories speak about the national condition of the Jewish people. If this understanding, filtered through my own experiences, was useful in reading Only Yesterday, it was essential in approaching Agnon’s late masterpiece A City in Its Fullness. This collection spans 300 years of the fictionalized and mythologized history of his Galician town Buczacz (in today’s western Ukraine). The author labored over this volume in the years before his death. He did not live to see it published; his daughter Emuna Yaron released it three years after his death.

A City in Its Fullness bears witness to how Agnon carried his hometown and its stories with him throughout his life, and the degree to which he saw himself as the literary chronicler of Buczacz. The long-held awareness that his town had been in danger of collapse, spiritually as well as physically, long before the Nazis arrived, and the impulse to document Buczacz in literature was obviously deeply rooted in his childhood experience. In fact, from his earliest years as a writer, in the first decade of the twentieth century, he had already set this as one of his areas of focus, although his narrative voice would mature and, indeed, sharply transition over the decades. In 1956, when his published output had slackened, he answered Israeli literary critic Baruch Kurzweil’s inquiry as to where he was focusing his energy: “I am building a city—Buczacz!” The late scholar Alan Mintz carefully observed that this statement was the “proprietary stamp of a veteran writer who writes using an established repertoire of modernist techniques. Reimagining Buczacz through the filter of this imagination that abandons nothing from the toolkit of modernism must of necessity mean creating something new, a new city. The bricks and mortar may be taken from the historical record, but the building will be a new creation. No other writer in modern Jewish culture has attempted a project of similar scope or ambition.”

This last point has become especially clear in this past decade, as Agnon’s last Buczacz tales have begun to receive the level of critical attention they deserve. A City in Its Fullness was Agnon’s epic literary memorial to Buczacz. Published in 1973, the book was largely overlooked, partially due to the bad timing of appearing on the eve of the Yom Kippur War, but more so due to the lack of appetite of that generation’s Hebrew readers for old world stories.

Agnon’s early writings are marked by a harsh critical eye, spotlighting hypocrisy and deception, especially relating to financial matters and social injustice. Only as Agnon matures is his focus on physical poverty (which remains ever present in his writing) overtaken by a portrayal of the spiritual poverty of Buczacz, as a synecdoche of Jewry writ large.

A penchant for self-mockery (especially by a middle-aged writer of his adolescent self) does not imply that Agnon lost or abandoned his critical perspective on his hometown as he aged. This was an authorial voice that was simply not available to a teenager unable to feel nostalgia for a town he had not yet left! Agnon departed Buczacz at age twenty, and, aside from two very brief visits, essentially never returned—yet his literary imagination was never far from his hometown, as if to say, “you can take the boy out of Buczacz, but you can’t take the Buczacz out of the boy.” Similar observations can and have been made about other great novelists; Mark Twain, James Joyce, William Faulkner, and Philip Roth all come to mind. Aharon Appelfeld’s appreciation for what he learned as a young author from Agnon expresses this quite precisely:

Most of my generation [of fellow authors] invested a huge amount of effort into suppressing and eradicating their past. I have absolutely no complaints against them; I understand them completely. But I, for some reason, didn’t know how to assimilate into the Israeli reality. Instead, I retreated into myself. For this, Agnon served as an excellent role model. It was from him that I learned how you can carry the town of your birth with you anywhere and live a full life in it. Your birthplace is not a matter of fixed geography. And you can extend its borders outward or raise them to the skies. Agnon populated his birthplace with everything the Jewish people had created in the past two hundred years. Like any great writer, he wrote not literal reminiscences of his town, not what it actually was, but what it could have been. And he taught me that a person’s past—even a difficult one—is not to be regarded as a defect or a disgrace, but as a legitimate source to be mined (Appelfeld, The Story of a Life, 153).

All this suggests that Agnon had to “leave his country and his homeland and his city and ascended to Eretz Yisraʾel to build it from its destruction and to be rebuilt by it,” so that he could turn his attention back to that city of Buczacz to rebuild it in literature. This is not to say that Agnon ever abandoned his critique, nor that he was unable to retain his cynicism as he aged. Indeed, A City in Its Fullness is awash in such social criticism, bordering on outright indictment of the communal leadership and the corrosive effects of vanity and power on Jewish life. Among the objects of particular concern are the oppression of the poor and the gap between the town’s expressed ideals as a religious community versus its sometimes-shoddy application in practice. The book bears a dedication to a city that “was full of Torah, wisdom, love, piety, life, grace, kindness and charity”; its content often tells a different tale (alternating between acidic or good humor). The essential difference between his early and later career is how Agnon learned to temper the youthful critique. He did this out of artistic impulse: writers who cannot evolve past the persona and voice crafted by their teenage narrators tend not to be recognized by the Nobel committee. But it was also a desire not to be a shill for the old world, nor attempt to deconstruct it. The proclivity of an author to venerate or satirize a world he depicts does not, in and of itself, indicate his stance vis-à-vis that world. In the case of Agnon, it was neither one nor the other but a desire to simultaneously skewer and sacralize and, in so doing, ask what that world of the past has to say to the present and future. It is this last insight which makes Agnon and his writing worthy of our attention even now, a half-century since his passing.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.