In 1980, Israeli artist Jacob Gildor (born in 1948) was among the founders of Meshushe (Hexagon) group, which aimed to introduce Surrealist art to the Israeli art space – still dominated by abstract and conceptual art movements at that time. Back in 1971, Gildor had been invited by the Surrealist artist and teacher Professor Ernst Fuchs to Reichenau, Austria, to learn the master’s unique technique in tempera. A close friendship was forged between the teacher and student, which opened the young artist to the Surrealist movement and led him and his peers to establish Meshushe. The founding group consisted of Gildor and five other Surrealists: Baruch Elron, Yoav Shuali, Arie Lamdan, Asher Rodnitzky, and Rachel Timor. The Meshushe group held 10 exhibitions throughout Israel. While the exhibitions were warmly received and admired by the Israeli audience, Meshushe’s Israeli attempt at the escapism of Surrealism never managed to enter the Israeli Canon of Art critiques.[20] Surrealism did not find admiration in the Israeli art scene. It did not speak to the intensity of ‘The Turning Generation’ and its urgent artistic and political expression on the present moment in Israel in the 1980s. Meshushe found itself marginalized and irrelevant. Ultimately, each artist went on to explore a variety of other styles, each finding it hard not to relate to the history, symbols, and narrative of the Jewish people and the present Israeli landscapes or cityscapes they were encountering in their art. While Salomon and Gildor had some overlap of influence by the Shoah (Gildor was Second Generation), the impact of Surrealism, and exploration of woe, they worked in parallel spaces, not recognizing the similarities of their styles and subject matters sprouting from their mutual hometown of Holon, Israel. It is unclear why Salomon was not involved with this group.

At one point in Salomon’s career – despite his home in Holon, art pieces explicitly exploring the 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, and 1993 Oslo Accords, and having his artwork displayed in the President’s residence in Jerusalem – he was still told by the leading Israeli art historian Gideon Ofrat: “You are not an Israeli painter. [אתה לא צייר ישראלי]”[21] An artist’s relations between homeland and Diaspora are complicated as they negotiate their identity through a complex psychological process of dramatic self-adjustment. As Sigal Barkai concludes:

“A new negotiation between local and universal cultural identities changes the

demarcation of Israeliness, and obscures outdated national ideas such as the negation of the Diaspora. It allows for mutually-nourishing artistic and societal formations that inspire the Israeli, Jewish, and global ‘imaginary community.’”[22]

Israeli art is eclectic, and very hard to define, specifically due to global mobility and influence, as well as post-immigration hyphenated identities – like Salomon’s Romanian-Israeli identity. The ethos of negation of exile, and the attempted melting pot of perceived ‘weak’ Diaspora Jews into the new native Israeli identity of strength, greatly troubled Salomon. Salomon was proud of his Romanian upbringing, despite ultimately being persecuted and rejected because he was a Jew. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin suggests:

“In its elementary and most common sense, the phrase “return to history” was perceived as signifying the intention of turning the dispersed Jews into a sovereign national subject that can determine its own fate and assume responsibility for its own existence. In that sense Zionism was considered to be the solution to the Jewish question and the conclusion of both the crisis of Jewish existence and the prominent role of anti-Semitism in modern culture. It was based on the accepted interpretation of the term “history” in nineteenth-century culture, which made the nation its exclusive subject and carrier.”[23]

Negation of exile is thus a cultural force in the construction of Zionism from the late nineteenth century to the present. It builds on the denying of specific features in Jewish histories that may “dangerously” contradict the image of national revival in the Land of Israel. Thus, it is only logical that Salomon’s European-influenced paintings were hard to place in the Israeli art scene, marginalized by his contemporaries – in a place of bitter isolation, an empty space filled by his studio.

Historian and educator Dr. Ori Soltes considers Israeli art “radicant art.” A radicant plant grows its roots, spreads, and adds new roots as it advances, with multiple enrootings along the way, just like an immigrant and their art. Salomon’s career in many ways is an example of immigrant radicant art adapting, evolving and enrooting anew along one’s journey of immigration to new places, and the identity transformation that coincides with changes of location and a new local reality and mindset. Salomon shifts from Realism and portraiture in Romania, to Cubism and Abstraction and Neo-Expressionism in young Israel, to then the quasi-Surrealistic and metaphoric animal jungle of his mind on canvas as the years go on and he and the Israeli art scene mature.

Artistic play becomes a therapeutic means of working through strong emotions due to social and internal dissonance for Salomon. The gradual merging of homeland and Diaspora bring forth a new cultural identity and a variety of ways to belong, the art being a means to an end of psychological processing and reconciliations, brought on by new and converging global and mobile realities.

Salomon explores not just Jewish survival, but also the struggles of masculinity and motherhood. He explores predators hunting their prey. He explores the dark sides of human nature, perhaps in ways that were indeed taboo and ahead of his time, as a radicant artist enrooting himself in the intensity of the Middle East. We can clearly see over time through his artwork a nuanced change in Salomon as an individual artist, but also of the wider social scene of his day, deriving meaning from and giving form to life experiences in the wake of wars, especially the 1982 Lebanon War.

In Fall 2023 we marked the 50th anniversary of a formative event in the Cold War, a defining moment in the geopolitics of the Middle East, and one of the direst trials for the young state of Israel: the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Though this War ended in a military victory for Israel, the invasion by Egypt and Syria and the days of anguished battle that followed threatened the very existence of the Jewish state. The war had dramatic and long-range impact as well: the politics, culture, and national-security strategy of Israel were forever altered, as were the USA, the Soviet Union, Egypt, and the rest of the Arab world likewise deeply affected.[24] Salomon investigated this existentially precarious moment for the young Jewish state in his pieces The Tank and Yom Kippur the very next year, 1974. The blood red of Jewish spirit is depicted in Yom Kippur with tanks pouring out light, driven by bulls above in a herd of strength, almost a divinely protective pillar of cloud: a very moving exploration of this crisis. The animal imagery and symbolism portray defensive strength and ultimately victory for Jewish survival. Yom Kippur is also an early example of him finding his artistic voice in his unique, existential art style of ‘Like Animals,’ investigating human behavior through quasi-Surrealist animal imagery – the style he spends the majority of his career exploring, perfecting, and exhibiting around the world.

Salomon’s ‘Like Animals’ Existential Art: Investigating Human Behavior through Surrealistic Animal Imagery

Postwar Surrealism established itself in relation to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism emphasizing that our acts create our essence, the humanist cultural policies of the French Communist Party articulated by Louis Aragon, and the re-emerging Parisian avant-garde. A Surrealist imposes meaning on the absurdity of the universe in an artistic way; effectively creating his own reality. The paintings of Surrealism, which are open to interpretation, can become whatever the viewer decides. In the face of existential agony, the existentialist exercises the human freedom to choose a meaningful life course, while the Surrealist chooses to impose meaning on elemental chaos through art. Salomon’s animals seem to work through the chaos of human violence and survival, partially focusing on the basic existential givens, including death and isolation.

Surrealism was a melting pot of avant-garde ideas and techniques still influential today, especially the introduction of chance elements. This new mode of painterly practice also blazed a trail for Abstract Expressionists, such as the Surrealist navigation of the unconscious and the Jungian symbolism of Jackson Pollock’s action painting. According to the theory of psychologist Carl Jung, symbols are language or images that convey, by means of concrete reality, something hidden or unknown and dimly perceived by the conscious mind. These symbols can never be fully understood by the conscious mind. Salomon included chance and a release of the unconscious in his technique for paper with oils on which he used special chemicals to create burst effects, releasing the image of his subjects from his paint layers, like in Camouflage.

Salomon’s earliest available artwork on the struggle of life through fauna art, painted in the 1950s prior to his move to Israel, uses cats and fish to investigate Communist oppression over the masses of Romania; this is his piece Belșug și pentru pisici / Plenty for cats too, which is in the Cluj-Napoca Art Museum collection. The cats are the Communist officials, who are also competing amongst one another for power and wealth, and the fish are the average people being ruled over and starved of their freedom, like the fish taken from their water – unable to breath, unable to function. These motifs return in Salomon’s 1973 Wild Beasts, the year of the Yom Kippur War. Here it is harder to determine who is represented by which wild animal. Perhaps the rulers of the Arab nations who initiated the attack are the cats, battling even amongst each other for power and territory, with other Arab nations ominously looking on from the dark shadows of the background. The cats are forcefully sending their citizens into bloody battles, making them swim through the stream of blood while warring with Jews. Salomon’s return to this cat and fish motif after twenty years, emerging from an ominous, vast black background, is very interesting. In Communist Romania he dared not use red on his linocut, while in 1973 Israel the blood red was already a motif of Salomon’s oil and acrylic paintings. The ghostly white fish stand out and take up much of the foreground in both pieces, while the cats both come from and fade back into the dark abyss of cruelty.

Per artist and art scholar Professor Haim Maor, “The experience of the viewer observing the patina is not intellectual, but rather retinal. His eye revels in the sensorial-tactile, sensuous-physical and emotional dimension it invoked in him.” Salomon got this effect through his technique of layering and then scraping acrylic paint, a style he developed after visiting frescoes in Pompeii and exploring their patina. Patina is a thin layer of acquired change of surface due to age and exposure. Salomon tried to create a similar effect, but to do it instantaneously. He enjoyed layering his paint and then using a scalpel to cut away and expose surfaces, layering themes and motifs as well in order to dialogue with the eye of the spectator. Sometimes Salomon used paper with oils and special chemicals to cause color explosions, using paint throwing to bring his animal figures to the surface of the canvas. The spectator is drawn into the drama of the images physically through this exciting texturing, and then emotionally – oneself becoming a character of the scene.

Salomon pins the individual against the masses, the crippled single against the uncaring pack or vicious flock, like in his Cerberus (1995) and Marabou (1995). Nature is supreme and mankind has no true control. There is tainted hope of new life and renewal for the tragedy-worn mother. There is the endless threatening and threatened, fear of the unknown, falls and fights to the death; the great contrast of anxiety-ridden and tormented life against the strong will to live. So much of these essentially Salomon themes are captured in Salomon’s Coexistence (1993), portrayed through a determined bull pushing forward despite the persistent pecking of a flock of birds in an unrecognizable time and place, contextualized only by the painting’s title and 1993 date – the year The Oslo Accords were signed. Salomon seems to be asking about the nature of this relationship, of the bull and the birds, and of ‘coexistence’ in general. Does the bull gain more from the birds grooming his back in a symbiosis, or suffer from their endless parasitic nipping? Would he be better alone, or does he need the coexistence to survive? Who is friend and who is enemy? Salomon’s pieces are full of questions and not answers, as he pulls the spectator into a triangular viewer-artwork-artist dialogue using his play with color, texture, and perspective. The spectator is the primary character for Salomon, who loved posing quandaries. As Salomon declared, “There is no such thing as art for art’s sake, just as a postal stamp is no longer a stamp if it is issued only for stamp collectors.”[25]

The gathering of his herds for their forbidding fate just beyond the canvas is apocalyptic, an exploration by Salomon of the effects of speciesism and the persecution of Jews. As Zach proposes, on Salomon’s canvas the Greek mythological characters Eros, god of love and sexual desire, and Thanatos, the personification of death, are in a constant push and pull of masculine domineering and deadly predatory power, epitomized in Salomon’s masterpiece Feast (1990). Salomon is grappling with his burned-out, contemporary Israeli masculinity – brought on by endless violence in Israel since his immigration, from the Six-Day War (1967), to the War of Attrition (1967-70), to the Yom Kippur War (1973), to the Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon (1971-1982), to the 1982 Lebanon War (1982), to the South Lebanon conflict (1985-2000), to the First Intifada (1987-1993). The persistent violence and conflicts of young Israel led to constant existential anxiety, which strong male Israelis were supposed to overcome and conquer with confidence and bravery. His feasting vultures and wolves bring to light harsh themes of action and impotence, death and desire, and fear of death. Zach concludes about Salomon’s paintings that:

” . . . whoever tunes in correctly his inner ear will perceive the warm heartbeat – agonized and tormented or inspired by an ardent desire to live – that resounds here across the film of ice, the film of eternity.”[26]

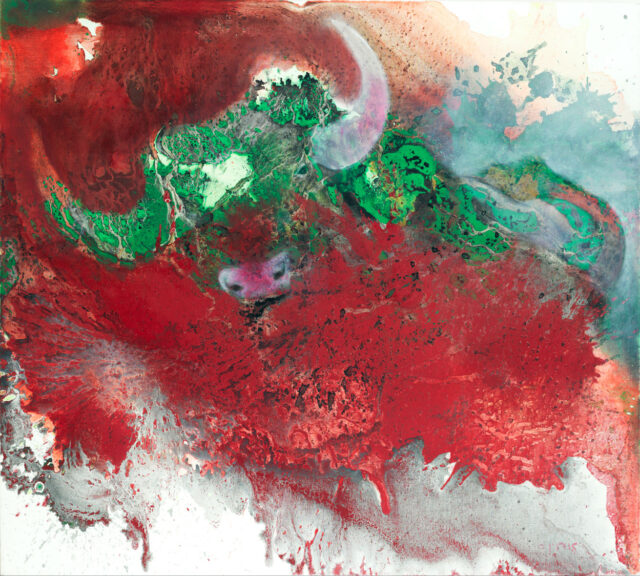

Ofrat views Salomon’s animals as rooted in the human wildness of subconscious passion, a contentious self-image of the artist. The unleashing of repressed aggression of leaping leopards and charging bulls culminates in Europa (2013), wherein Salomon’s inner bull still tries to charge forward out of the bursting blood red of his second bout of spreading cancer, exhaustion, and disappearing vigor the year before his passing. In fact, Europa Salomon painted with his son Tavi. Tavi helped Salomon with his paint throwing at this advanced stage of his illness, when much of his strength and desire was quickly vanishing. Through the paint throwing they brought out one of Salomon’s final bulls, his inner bull surfacing, faded, through the red cancer aggressively advancing and covering his knowing stance and surrendering gaze.

Ofrat, like Zach, also views Salomon’s paintings through the lens of Eros and Thanatos, death and sexual passion in dialogue on the canvas. Ofrat declares:

” . . . the painter draws his wild world from the ultimate roots of human wildness, namely sub-conscious passion. It is there, in between sex and the death of its lusts and fears, that Edwin Salomon’s herds wander.”[27]

Even Salomon’s garbage cats sexually courting, on the background of the Lebanon War ruins, are classic ‘Salomonistic’ combinations of Eros and Thanatos. His mental safari rouses malevolent spiritual entities from an anxiety ridden, frail world. Kedar too considers the mythological in Salomon’s approach, but of the god of the underworld, of Hades; Hades who invokes a repetitive purgatory where death being a part of life leads to endless punishment and atonement. Decay and existence feed off of and into each other perpetually. Salomon expresses, “In my view, death is not the opposite of life; rather it is its echo and metamorphosis.”[28] The use of animals to portray the waging of an existential war is seen as Salomon being “ahead of his time”[29] by contemporary Israeli artist Farid Abu Shakra.

In Egypt Salomon deals with a national-cultural memory from the story of the Exodus, and the symbolic death of the Egyptian pursuers of the Israelites into the Red Sea. He portrays them as shadowed, dissipating bulls coming up against the striking pillars of water of the split sea. This piece was done in 1982, the year that Israel invaded southern Lebanon following a series of attacks and counter-attacks between the Palestine Liberation Organization operating in southern Lebanon and the Israeli military that had caused civilian casualties on both sides of the border. It is a fascinating piece full of symbolism around power, death, existential threat, and freedom. Like Egypt, Salomon’s works continually contrast beginnings and endings in the face of violence and renewal, especially during this violent period in Israel. The 1982 Lebanon War inspired several ‘Like Animals’ existential artworks, from Salomon’s Ambush (1982), to Last Journey (1982), to End or Beginning (1982), to Oxygen Starved (1984).

Salomon blurs whole lines and missing lines, the present and a hallucination of the future, time and space into chaotic substance. The unknown backdrops upon which his animals wander evoke a feeling of unrest in the viewer. His herds gallop, jump and flee upon an existential emptiness, being either the charging mob of pogrom destruction or the fleeing, fear-filled prey. Life morphs into death. Creatures experience all pain and brutal force without restraint, while knowingly being captive to the cycle that nature has set up, from which there is no escape. For an example, see the ferocious protection of the mother tiger for her preyed-upon cub in Salomon’s Camouflage.

Camouflage was a loaded word for Salomon. He expressed:

“Camouflage in nature is part of the struggle for survival. The same camouflage is also manifested in my paintings, as the texture of the animal merges with the background. At times the animal is visible, at others – it remains concealed. The viewer must have the patience of a hunter in order to discern both worlds.”[30]

Here in Camouflage his technique utilizing chemicals and oil and acrylic paint throwing brings the animal figures to the surface of the canvas. In this later period and new style of his works, with the use of chemicals and paint throwing randomness, Salomon seems to be exploring a new form of animal representation. Salomon learns from the animal universe the visual language of camouflage, or the adaptation of an organism to its surroundings. At the visual level of an ecosystem, living organisms through their interrelations have a certain visual consequence, and Salomon here has brought this to his painting and to the medium of using paint on the canvas. During this paint throwing later period, Salomon at times breaks from symbols and allows himself to embrace non-conceptual, non-intellectual perception and basic animal-like sensorial response to the world around us.

Conclusion: Salomon and the Importance of a Respected Marginality

Understanding the Fate of Surrealistic Artists in the Jewish Israeli Art Scene

Salomon’s paintings have found themselves in the margins of Israeli art history. Perhaps this destiny was determined by his alienation as a radicant, immigrant artist in the throes of redefining his self-identity and grappling with taboo questions of his day, whether the Jewish existential crisis of the Shoah or the pain of the Yom Kippur War. His perception of Jewish history, the State of Israel, nationality, and a sense of belonging before and after immigration created a special nuance of style and quasi-Surrealism which was enhanced by the tension between homeland and diaspora, personal traumas, and the negotiation of cultural memory through multiple narratives and transitory realities.

Salomon’s multiple cultural identities were forged between history and culture, in a studio space where the constant play on canvas of memory, fantasy, narrative, and mythology further brought quasi-Surrealism to Israel through his animal jungle. His negotiation of local and universal cultural identities and existential ponderings brought the viewer into his questioning of contemporary events and societal realities of the Israeli, Jewish, and universal human communities through brilliant technique, texture, and color. Salomon did not want his artwork to be shown in galleries for only the elite, nor were they designed for mass commercial production. His dream was that his paintings would speak to everyone, but intimately. Salomon asserted, “The simple man should not stay apathetic (לא להישאר אדיש).”[31] He wanted his art to engage with the average man, to question him. Salomon also wanted to have his say in the world and find his voice through his painting and use of universal animal imagery and symbolism, especially in the face of his language barriers as an immigrant.

Viewing Salomon’s artworks in person is a wonderful adventure of texture and color springing from the canvases and papers, bringing to life the human experience through animal motifs in a swirl of movement and expressiveness. Each work is a revelry of layers, exciting surfaces that the eye engages with in delight. The first moments of viewing the pieces are retinally, physically stimulating – which in turn evokes an emotional and then intellectual engagement with the many components of the subject matter and its presentation. Salomon proclaimed, “The animal and the texture in my works are one. In their ‘struggle,’ the power balance alternates and each time another party will raise its head and have the upper hand.”[32] Salomon’s physical and spiritual accessing of the greater cosmos faces reality, and is yet surreal.

Edwin Salomon passed away in 2014. His ‘Like Animals’ art has left his questions to the world and strong comments on humanity, helping us to contemplate at a deeper level what it is to be a human being. Salomon’s paintings appear in numerous private collections in Israel, the USA, Canada, Uruguay, Brazil, Romania, Sweden, and Hungary, as well as in public collections such as the National Museum of Bucharest, the Cluj Museum, the Herzliya Museum, the President’s Residence in Jerusalem, and the Great Synagogue of Washington DC.

Salomon knew taboo issues had to be faced, and was exhibited exploring these questions with the viewer alongside younger contemporaries, particularly in the March 2013 exhibition “Like Animals” curated by Haim Maor. This exhibition presented artists passionate about using animal imagery to explore life inquiries, not escape them by fleeing into a full Surrealistic dream. The previously unfathomable first atomic bomb had been dropped and the Shoah had been perpetrated, and from the death and chaos of World War II it was hard to simply break from all reality and not engage with the harsh world and the memories it seared into the minds of European, and world, Jewry. Solomon’s fascinating quasi-Surrealist style breaks perspective lines and uses movement, brilliance of color, and unnaturalistic representations and expression to help us see the human as animal and bring us closer to certain elements of ourselves – even elements we would prefer not to face and have buried deep into the unconscious mind.

Salomon’s work and representations help us explore humans through animals – and when humans act as animals – across aesthetics, periods, and styles spanning his career of some 50 years. Salomon believed that animal fauna is the best tool to express true human nature, especially in the Middle East’s environment. His subject matter on human beings through the wild animal will help generations to come ponder the existential human experience.

[1] Tavi Salomon. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 23 August 2023.

[2] Farid Abu Shakra. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 27 December 2022.

[3] Gideon Ofrat. “Beauty and the Beast” in Edwin Salomon, edited by Jacques Soussana. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991.

[4] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Mechira Pumbit, Meiri Print: Holon, 2003, 32.

[5] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 104.

[6] Spirit of Creativity: Resistance Through Art During the Holocaust [Exhibition]. (2023). The Museum of Holocaust Art, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

[7] Jean Ancel(2002). History of the Holocaust – Romania (in Hebrew). Israel: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-157-8.

[8] Jean Ancel (2002). History of the Holocaust – Romania (in Hebrew). Israel: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-157-8. For details of the pogrom itself, see volume I, 363–400.

[9] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, p. 11.

[10] Spirit of Creativity: Resistance Through Art During the Holocaust [Exhibition]. (2023). The Museum of Holocaust Art, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

[11] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, 56.

[12] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 104-105.

[13] Douglas Murray. (13 October 2023). ‘You are not alone’: A message to the Jewish people. The Spectator.

[14] Haim N. Finkelstein. Surrealism and the Crisis of the Object. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University Microfilms International, 1979.

[15] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Towards 1958 – On the Human Condition’, 2008, 11.

[16] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 116.

[17] Dalia Manor, From Rejection to Recognition: Israeli Art and the Holocaust, 1998, 256.

[18] Dorit Kedar. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 12 October 2022.

[19] Yael Guilat,. The Turning Generation: Young Art in the Eighties in Israel

[דור המפנה; אמנות צעירה בשנות השמונים בישראל]. Oranim Academic College of Teaching. Kiryat Sde Boker: Ben Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 2019.

[20] Jacob Gildor. (Accessed 6 January 2024). Jacob Gildor. https://www.jacobgildor.com/bio2.

[21] Tavi Salomon. (2021, April 19). Edwin Salomon [PowerPoint slides]. Art History Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Research Seminar of Art History Spring 2021. Zoom Seminar.

[22] Sigal Barkai. ‘Neo-Diasporic Israeli Artists: Multiple Forms of Belonging’, 2021, 18.

[23] Amon Raz-Krakotzin. “Exile, History and the Nationalization of Jewish Memory: Some Reflections on the Zionist notion of History and Return,” Journal of Levantine Studies, 3.2 (Winter 2013), 37.

[24] Jonathan Silver, Senior Director of Tikvah Ideas, Warren R. Stern Senior Fellow of Jewish Civilization. (2023). 50th Anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. Tikvah Ideas.

[25] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Mechira Pumbit, Meiri Print: Holon, 2003. 15.

[26] Natan Zach, ‘The Animal Language of Edwin Salomon’, 1987, 8.

[27] Gideon Ofrat, Edwin Salomon’s Fauna, 1987, 1.

[28] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, 97.

[29] Farid Abu Shakra. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 27 December 2022.

[30] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Ravgon Ltd.: Herzliya, 2006. 46.

[31] Tavi Salomon. (2021, April 19). Edwin Salomon [PowerPoint slides]. Art History Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Research Seminar of Art History Spring 2021. Zoom Seminar.

[32] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Ravgon Ltd.: Herzliya, 2006. 28.

Inspired by Ardon, Bezem and Bak, upon his move to Israel in 1961, Salomon boldly worked to find his own language of signs and symbols, and also dealt with the taboo subject of the Holocaust. For example, Holocaust reflected directly on Nazi dehumanization tactics against Jews, a theme that would reverberate in Salomon’s artworks for decades. Through his unique animal imagery Salomon shows the rejected few in existential crisis brought on by the onlooking cruel masses and harsh officials of the regimes gawking at Jewish “otherness.” Salomon’s Bighorn, painted in 1980, shows an authority figure shepherding the masses up a treacherous mountain, with a smoky doom-filled sky of ashes alongside. Salomon’s use of marabou storks, rats, and fish schools reoccurs, shedding light on Salomon’s psychological distress around the stereotyping of exiled, frail, and/or submissive Jews, who in his memory were doomed to be persecuted and annihilated.

The Salomon of the Young State of Israel: A “Radicant” Art Immigrant Voice

Dorit Kedar (born 1948), an Israeli author and researcher specializing in gender and religion and longstanding colleague of Salomon’s and educator at HaMidrasha School of Art, recalls that Salomon loved classical Western culture and philosophy. He had trouble being understood in the local Israeli art scene, often on the outskirts of the dialogue on art of the HaMidrasha faculty he taught on for over a decade.[18] HaMidrasha attempted to educate its art students conceptually as “artists” and expected that they would develop their technical skills independently, in accordance with their individual needs. It was in this milieu that Salomon brought up a generation of sabra/native Israeli artists, from Haim Maor (who studied under him from 1961-68 and went on to be a full Professor of Art at Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva) to Yigal Ozeri (a leading Photorealism painter now based in New York City). Regardless of his personal painting prowess and excellence as a mentor, Salomon still felt an odd man out, as he did not conform to the style of his colleagues. During the rise of conceptual art in Israel in the 1960s and 70s, art for which the idea behind the work is more important than the finished art object (some works of conceptual art may be produced by anyone following a set of written instructions), Salomon still focused on the fundamentals and excellence of technique in his own artwork.

Salomon honed his unique, animal-Surrealistic motif as an Israeli artist in the 1980s. In 1983 Salomon won the Prize for Creativity from the Beit Hatanach (Bible Museum), Tel Aviv – a venue primarily outside of the artistic circle that displays permanent exhibits depicting the times of our forefathers, but which also has temporary exhibits of art related to the bible, Judaism and the Land of Israel. Edwin and his contemporaries were encountering the Neo-Expressionism of the international scene and finding their own expressive modes of representation. Israeli artists from this era, such as Moshe Gershuni, tended to work with blood-red paint, as if renewing a blood-bound covenant with the Land. Salomon’s blood red, which runs throughout his decades of painting, including Prayers pictured here, have tinges of this theme in its hue. Here a pack of tigers roar to the abyss of the heavens in prayer. One tiger slightly stands out – an individual in contrasting, strong yellows against the pack. Only the tints of red and blue coming through the darkness of the background help distinguish the wider masses from endlessness beyond the canvas.

The 1980s were a transitional period for Israeli art, marking the beginning of contemporary art in Israel. There was a break away from the unity of formative ideas of Israeli identity as a new, robust generation of artists rose to the art scene. Professor of Visual Culture and Art History Dr. Yael Guilat calls the young artists in the 80s in Israel ‘The Turning Generation’ [דור המפנה]. Guilat explores how ‘The Turning Generation’ revealed a generation of artists who were forced to dismantle myths and break previous paradigms; a generation of young female artists who worked in a male-dominated field; a young generation that was accused of being reactionary and unsophisticated, but whose work was characterized by a strong and urgent artistic and political expression; a generation that acted in an unprecedented burst of energy, and for whom art was a multi-channel field of action, invention, protest, and disillusionment. The young artists that emerged from the beginning of the decade both shaped it and were shaped by it, as is reflected in changes that were made in the field of curation, in the medium field, and in the thematic-stylistic field. Looking at the multi-faceted portrait of the younger generation of artists who worked in the 1980s reveals the collapse of the imagined portrait of Israeli society.[19]

The energy of ‘The Turning Generation’ renewed Salomon’s inspiration. The 80s were a decade of tremendous output by Salomon and a push to participate in exhibitions, even at venues at the margins of the art scene of the time. The 1980s brought more private and public gallery spaces and alternative exhibition venues, which Salomon used as an opportunity to exhibit his works more often. This included his participation in several one-man shows in Israel, as well as group exhibitions in Israel, Europe, and the USA. Like others of this time period who did not fit into the zeitgeist – the Israeli style of art Want of Matter [דלות החומר], which utilized meager creative materials to be socially critical – Salomon remained outside the mainstream and distinct from the definition of ‘Israeli art.’ Despite that fact, Salomon wanted to be responsible for the public seeing his own art, instead of waiting for a curator to discover him, and successfully exhibited throughout the decade.

In 1980, Israeli artist Jacob Gildor (born in 1948) was among the founders of Meshushe (Hexagon) group, which aimed to introduce Surrealist art to the Israeli art space – still dominated by abstract and conceptual art movements at that time. Back in 1971, Gildor had been invited by the Surrealist artist and teacher Professor Ernst Fuchs to Reichenau, Austria, to learn the master’s unique technique in tempera. A close friendship was forged between the teacher and student, which opened the young artist to the Surrealist movement and led him and his peers to establish Meshushe. The founding group consisted of Gildor and five other Surrealists: Baruch Elron, Yoav Shuali, Arie Lamdan, Asher Rodnitzky, and Rachel Timor. The Meshushe group held 10 exhibitions throughout Israel. While the exhibitions were warmly received and admired by the Israeli audience, Meshushe’s Israeli attempt at the escapism of Surrealism never managed to enter the Israeli Canon of Art critiques.[20] Surrealism did not find admiration in the Israeli art scene. It did not speak to the intensity of ‘The Turning Generation’ and its urgent artistic and political expression on the present moment in Israel in the 1980s. Meshushe found itself marginalized and irrelevant. Ultimately, each artist went on to explore a variety of other styles, each finding it hard not to relate to the history, symbols, and narrative of the Jewish people and the present Israeli landscapes or cityscapes they were encountering in their art. While Salomon and Gildor had some overlap of influence by the Shoah (Gildor was Second Generation), the impact of Surrealism, and exploration of woe, they worked in parallel spaces, not recognizing the similarities of their styles and subject matters sprouting from their mutual hometown of Holon, Israel. It is unclear why Salomon was not involved with this group.

At one point in Salomon’s career – despite his home in Holon, art pieces explicitly exploring the 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, and 1993 Oslo Accords, and having his artwork displayed in the President’s residence in Jerusalem – he was still told by the leading Israeli art historian Gideon Ofrat: “You are not an Israeli painter. [אתה לא צייר ישראלי]”[21] An artist’s relations between homeland and Diaspora are complicated as they negotiate their identity through a complex psychological process of dramatic self-adjustment. As Sigal Barkai concludes:

“A new negotiation between local and universal cultural identities changes the

demarcation of Israeliness, and obscures outdated national ideas such as the negation of the Diaspora. It allows for mutually-nourishing artistic and societal formations that inspire the Israeli, Jewish, and global ‘imaginary community.’”[22]

Israeli art is eclectic, and very hard to define, specifically due to global mobility and influence, as well as post-immigration hyphenated identities – like Salomon’s Romanian-Israeli identity. The ethos of negation of exile, and the attempted melting pot of perceived ‘weak’ Diaspora Jews into the new native Israeli identity of strength, greatly troubled Salomon. Salomon was proud of his Romanian upbringing, despite ultimately being persecuted and rejected because he was a Jew. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin suggests:

“In its elementary and most common sense, the phrase “return to history” was perceived as signifying the intention of turning the dispersed Jews into a sovereign national subject that can determine its own fate and assume responsibility for its own existence. In that sense Zionism was considered to be the solution to the Jewish question and the conclusion of both the crisis of Jewish existence and the prominent role of anti-Semitism in modern culture. It was based on the accepted interpretation of the term “history” in nineteenth-century culture, which made the nation its exclusive subject and carrier.”[23]

Negation of exile is thus a cultural force in the construction of Zionism from the late nineteenth century to the present. It builds on the denying of specific features in Jewish histories that may “dangerously” contradict the image of national revival in the Land of Israel. Thus, it is only logical that Salomon’s European-influenced paintings were hard to place in the Israeli art scene, marginalized by his contemporaries – in a place of bitter isolation, an empty space filled by his studio.

Historian and educator Dr. Ori Soltes considers Israeli art “radicant art.” A radicant plant grows its roots, spreads, and adds new roots as it advances, with multiple enrootings along the way, just like an immigrant and their art. Salomon’s career in many ways is an example of immigrant radicant art adapting, evolving and enrooting anew along one’s journey of immigration to new places, and the identity transformation that coincides with changes of location and a new local reality and mindset. Salomon shifts from Realism and portraiture in Romania, to Cubism and Abstraction and Neo-Expressionism in young Israel, to then the quasi-Surrealistic and metaphoric animal jungle of his mind on canvas as the years go on and he and the Israeli art scene mature.

Artistic play becomes a therapeutic means of working through strong emotions due to social and internal dissonance for Salomon. The gradual merging of homeland and Diaspora bring forth a new cultural identity and a variety of ways to belong, the art being a means to an end of psychological processing and reconciliations, brought on by new and converging global and mobile realities.

Salomon explores not just Jewish survival, but also the struggles of masculinity and motherhood. He explores predators hunting their prey. He explores the dark sides of human nature, perhaps in ways that were indeed taboo and ahead of his time, as a radicant artist enrooting himself in the intensity of the Middle East. We can clearly see over time through his artwork a nuanced change in Salomon as an individual artist, but also of the wider social scene of his day, deriving meaning from and giving form to life experiences in the wake of wars, especially the 1982 Lebanon War.

In Fall 2023 we marked the 50th anniversary of a formative event in the Cold War, a defining moment in the geopolitics of the Middle East, and one of the direst trials for the young state of Israel: the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Though this War ended in a military victory for Israel, the invasion by Egypt and Syria and the days of anguished battle that followed threatened the very existence of the Jewish state. The war had dramatic and long-range impact as well: the politics, culture, and national-security strategy of Israel were forever altered, as were the USA, the Soviet Union, Egypt, and the rest of the Arab world likewise deeply affected.[24] Salomon investigated this existentially precarious moment for the young Jewish state in his pieces The Tank and Yom Kippur the very next year, 1974. The blood red of Jewish spirit is depicted in Yom Kippur with tanks pouring out light, driven by bulls above in a herd of strength, almost a divinely protective pillar of cloud: a very moving exploration of this crisis. The animal imagery and symbolism portray defensive strength and ultimately victory for Jewish survival. Yom Kippur is also an early example of him finding his artistic voice in his unique, existential art style of ‘Like Animals,’ investigating human behavior through quasi-Surrealist animal imagery – the style he spends the majority of his career exploring, perfecting, and exhibiting around the world.

Salomon’s ‘Like Animals’ Existential Art: Investigating Human Behavior through Surrealistic Animal Imagery

Postwar Surrealism established itself in relation to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism emphasizing that our acts create our essence, the humanist cultural policies of the French Communist Party articulated by Louis Aragon, and the re-emerging Parisian avant-garde. A Surrealist imposes meaning on the absurdity of the universe in an artistic way; effectively creating his own reality. The paintings of Surrealism, which are open to interpretation, can become whatever the viewer decides. In the face of existential agony, the existentialist exercises the human freedom to choose a meaningful life course, while the Surrealist chooses to impose meaning on elemental chaos through art. Salomon’s animals seem to work through the chaos of human violence and survival, partially focusing on the basic existential givens, including death and isolation.

Surrealism was a melting pot of avant-garde ideas and techniques still influential today, especially the introduction of chance elements. This new mode of painterly practice also blazed a trail for Abstract Expressionists, such as the Surrealist navigation of the unconscious and the Jungian symbolism of Jackson Pollock’s action painting. According to the theory of psychologist Carl Jung, symbols are language or images that convey, by means of concrete reality, something hidden or unknown and dimly perceived by the conscious mind. These symbols can never be fully understood by the conscious mind. Salomon included chance and a release of the unconscious in his technique for paper with oils on which he used special chemicals to create burst effects, releasing the image of his subjects from his paint layers, like in Camouflage.

Salomon’s earliest available artwork on the struggle of life through fauna art, painted in the 1950s prior to his move to Israel, uses cats and fish to investigate Communist oppression over the masses of Romania; this is his piece Belșug și pentru pisici / Plenty for cats too, which is in the Cluj-Napoca Art Museum collection. The cats are the Communist officials, who are also competing amongst one another for power and wealth, and the fish are the average people being ruled over and starved of their freedom, like the fish taken from their water – unable to breath, unable to function. These motifs return in Salomon’s 1973 Wild Beasts, the year of the Yom Kippur War. Here it is harder to determine who is represented by which wild animal. Perhaps the rulers of the Arab nations who initiated the attack are the cats, battling even amongst each other for power and territory, with other Arab nations ominously looking on from the dark shadows of the background. The cats are forcefully sending their citizens into bloody battles, making them swim through the stream of blood while warring with Jews. Salomon’s return to this cat and fish motif after twenty years, emerging from an ominous, vast black background, is very interesting. In Communist Romania he dared not use red on his linocut, while in 1973 Israel the blood red was already a motif of Salomon’s oil and acrylic paintings. The ghostly white fish stand out and take up much of the foreground in both pieces, while the cats both come from and fade back into the dark abyss of cruelty.

Per artist and art scholar Professor Haim Maor, “The experience of the viewer observing the patina is not intellectual, but rather retinal. His eye revels in the sensorial-tactile, sensuous-physical and emotional dimension it invoked in him.” Salomon got this effect through his technique of layering and then scraping acrylic paint, a style he developed after visiting frescoes in Pompeii and exploring their patina. Patina is a thin layer of acquired change of surface due to age and exposure. Salomon tried to create a similar effect, but to do it instantaneously. He enjoyed layering his paint and then using a scalpel to cut away and expose surfaces, layering themes and motifs as well in order to dialogue with the eye of the spectator. Sometimes Salomon used paper with oils and special chemicals to cause color explosions, using paint throwing to bring his animal figures to the surface of the canvas. The spectator is drawn into the drama of the images physically through this exciting texturing, and then emotionally – oneself becoming a character of the scene.

Salomon pins the individual against the masses, the crippled single against the uncaring pack or vicious flock, like in his Cerberus (1995) and Marabou (1995). Nature is supreme and mankind has no true control. There is tainted hope of new life and renewal for the tragedy-worn mother. There is the endless threatening and threatened, fear of the unknown, falls and fights to the death; the great contrast of anxiety-ridden and tormented life against the strong will to live. So much of these essentially Salomon themes are captured in Salomon’s Coexistence (1993), portrayed through a determined bull pushing forward despite the persistent pecking of a flock of birds in an unrecognizable time and place, contextualized only by the painting’s title and 1993 date – the year The Oslo Accords were signed. Salomon seems to be asking about the nature of this relationship, of the bull and the birds, and of ‘coexistence’ in general. Does the bull gain more from the birds grooming his back in a symbiosis, or suffer from their endless parasitic nipping? Would he be better alone, or does he need the coexistence to survive? Who is friend and who is enemy? Salomon’s pieces are full of questions and not answers, as he pulls the spectator into a triangular viewer-artwork-artist dialogue using his play with color, texture, and perspective. The spectator is the primary character for Salomon, who loved posing quandaries. As Salomon declared, “There is no such thing as art for art’s sake, just as a postal stamp is no longer a stamp if it is issued only for stamp collectors.”[25]

The gathering of his herds for their forbidding fate just beyond the canvas is apocalyptic, an exploration by Salomon of the effects of speciesism and the persecution of Jews. As Zach proposes, on Salomon’s canvas the Greek mythological characters Eros, god of love and sexual desire, and Thanatos, the personification of death, are in a constant push and pull of masculine domineering and deadly predatory power, epitomized in Salomon’s masterpiece Feast (1990). Salomon is grappling with his burned-out, contemporary Israeli masculinity – brought on by endless violence in Israel since his immigration, from the Six-Day War (1967), to the War of Attrition (1967-70), to the Yom Kippur War (1973), to the Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon (1971-1982), to the 1982 Lebanon War (1982), to the South Lebanon conflict (1985-2000), to the First Intifada (1987-1993). The persistent violence and conflicts of young Israel led to constant existential anxiety, which strong male Israelis were supposed to overcome and conquer with confidence and bravery. His feasting vultures and wolves bring to light harsh themes of action and impotence, death and desire, and fear of death. Zach concludes about Salomon’s paintings that:

” . . . whoever tunes in correctly his inner ear will perceive the warm heartbeat – agonized and tormented or inspired by an ardent desire to live – that resounds here across the film of ice, the film of eternity.”[26]

Ofrat views Salomon’s animals as rooted in the human wildness of subconscious passion, a contentious self-image of the artist. The unleashing of repressed aggression of leaping leopards and charging bulls culminates in Europa (2013), wherein Salomon’s inner bull still tries to charge forward out of the bursting blood red of his second bout of spreading cancer, exhaustion, and disappearing vigor the year before his passing. In fact, Europa Salomon painted with his son Tavi. Tavi helped Salomon with his paint throwing at this advanced stage of his illness, when much of his strength and desire was quickly vanishing. Through the paint throwing they brought out one of Salomon’s final bulls, his inner bull surfacing, faded, through the red cancer aggressively advancing and covering his knowing stance and surrendering gaze.

Ofrat, like Zach, also views Salomon’s paintings through the lens of Eros and Thanatos, death and sexual passion in dialogue on the canvas. Ofrat declares:

” . . . the painter draws his wild world from the ultimate roots of human wildness, namely sub-conscious passion. It is there, in between sex and the death of its lusts and fears, that Edwin Salomon’s herds wander.”[27]

Even Salomon’s garbage cats sexually courting, on the background of the Lebanon War ruins, are classic ‘Salomonistic’ combinations of Eros and Thanatos. His mental safari rouses malevolent spiritual entities from an anxiety ridden, frail world. Kedar too considers the mythological in Salomon’s approach, but of the god of the underworld, of Hades; Hades who invokes a repetitive purgatory where death being a part of life leads to endless punishment and atonement. Decay and existence feed off of and into each other perpetually. Salomon expresses, “In my view, death is not the opposite of life; rather it is its echo and metamorphosis.”[28] The use of animals to portray the waging of an existential war is seen as Salomon being “ahead of his time”[29] by contemporary Israeli artist Farid Abu Shakra.

In Egypt Salomon deals with a national-cultural memory from the story of the Exodus, and the symbolic death of the Egyptian pursuers of the Israelites into the Red Sea. He portrays them as shadowed, dissipating bulls coming up against the striking pillars of water of the split sea. This piece was done in 1982, the year that Israel invaded southern Lebanon following a series of attacks and counter-attacks between the Palestine Liberation Organization operating in southern Lebanon and the Israeli military that had caused civilian casualties on both sides of the border. It is a fascinating piece full of symbolism around power, death, existential threat, and freedom. Like Egypt, Salomon’s works continually contrast beginnings and endings in the face of violence and renewal, especially during this violent period in Israel. The 1982 Lebanon War inspired several ‘Like Animals’ existential artworks, from Salomon’s Ambush (1982), to Last Journey (1982), to End or Beginning (1982), to Oxygen Starved (1984).

Salomon blurs whole lines and missing lines, the present and a hallucination of the future, time and space into chaotic substance. The unknown backdrops upon which his animals wander evoke a feeling of unrest in the viewer. His herds gallop, jump and flee upon an existential emptiness, being either the charging mob of pogrom destruction or the fleeing, fear-filled prey. Life morphs into death. Creatures experience all pain and brutal force without restraint, while knowingly being captive to the cycle that nature has set up, from which there is no escape. For an example, see the ferocious protection of the mother tiger for her preyed-upon cub in Salomon’s Camouflage.

Camouflage was a loaded word for Salomon. He expressed:

“Camouflage in nature is part of the struggle for survival. The same camouflage is also manifested in my paintings, as the texture of the animal merges with the background. At times the animal is visible, at others – it remains concealed. The viewer must have the patience of a hunter in order to discern both worlds.”[30]

Here in Camouflage his technique utilizing chemicals and oil and acrylic paint throwing brings the animal figures to the surface of the canvas. In this later period and new style of his works, with the use of chemicals and paint throwing randomness, Salomon seems to be exploring a new form of animal representation. Salomon learns from the animal universe the visual language of camouflage, or the adaptation of an organism to its surroundings. At the visual level of an ecosystem, living organisms through their interrelations have a certain visual consequence, and Salomon here has brought this to his painting and to the medium of using paint on the canvas. During this paint throwing later period, Salomon at times breaks from symbols and allows himself to embrace non-conceptual, non-intellectual perception and basic animal-like sensorial response to the world around us.

Conclusion: Salomon and the Importance of a Respected Marginality

Understanding the Fate of Surrealistic Artists in the Jewish Israeli Art Scene

Salomon’s paintings have found themselves in the margins of Israeli art history. Perhaps this destiny was determined by his alienation as a radicant, immigrant artist in the throes of redefining his self-identity and grappling with taboo questions of his day, whether the Jewish existential crisis of the Shoah or the pain of the Yom Kippur War. His perception of Jewish history, the State of Israel, nationality, and a sense of belonging before and after immigration created a special nuance of style and quasi-Surrealism which was enhanced by the tension between homeland and diaspora, personal traumas, and the negotiation of cultural memory through multiple narratives and transitory realities.

Salomon’s multiple cultural identities were forged between history and culture, in a studio space where the constant play on canvas of memory, fantasy, narrative, and mythology further brought quasi-Surrealism to Israel through his animal jungle. His negotiation of local and universal cultural identities and existential ponderings brought the viewer into his questioning of contemporary events and societal realities of the Israeli, Jewish, and universal human communities through brilliant technique, texture, and color. Salomon did not want his artwork to be shown in galleries for only the elite, nor were they designed for mass commercial production. His dream was that his paintings would speak to everyone, but intimately. Salomon asserted, “The simple man should not stay apathetic (לא להישאר אדיש).”[31] He wanted his art to engage with the average man, to question him. Salomon also wanted to have his say in the world and find his voice through his painting and use of universal animal imagery and symbolism, especially in the face of his language barriers as an immigrant.

Viewing Salomon’s artworks in person is a wonderful adventure of texture and color springing from the canvases and papers, bringing to life the human experience through animal motifs in a swirl of movement and expressiveness. Each work is a revelry of layers, exciting surfaces that the eye engages with in delight. The first moments of viewing the pieces are retinally, physically stimulating – which in turn evokes an emotional and then intellectual engagement with the many components of the subject matter and its presentation. Salomon proclaimed, “The animal and the texture in my works are one. In their ‘struggle,’ the power balance alternates and each time another party will raise its head and have the upper hand.”[32] Salomon’s physical and spiritual accessing of the greater cosmos faces reality, and is yet surreal.

Edwin Salomon passed away in 2014. His ‘Like Animals’ art has left his questions to the world and strong comments on humanity, helping us to contemplate at a deeper level what it is to be a human being. Salomon’s paintings appear in numerous private collections in Israel, the USA, Canada, Uruguay, Brazil, Romania, Sweden, and Hungary, as well as in public collections such as the National Museum of Bucharest, the Cluj Museum, the Herzliya Museum, the President’s Residence in Jerusalem, and the Great Synagogue of Washington DC.

Salomon knew taboo issues had to be faced, and was exhibited exploring these questions with the viewer alongside younger contemporaries, particularly in the March 2013 exhibition “Like Animals” curated by Haim Maor. This exhibition presented artists passionate about using animal imagery to explore life inquiries, not escape them by fleeing into a full Surrealistic dream. The previously unfathomable first atomic bomb had been dropped and the Shoah had been perpetrated, and from the death and chaos of World War II it was hard to simply break from all reality and not engage with the harsh world and the memories it seared into the minds of European, and world, Jewry. Solomon’s fascinating quasi-Surrealist style breaks perspective lines and uses movement, brilliance of color, and unnaturalistic representations and expression to help us see the human as animal and bring us closer to certain elements of ourselves – even elements we would prefer not to face and have buried deep into the unconscious mind.

Salomon’s work and representations help us explore humans through animals – and when humans act as animals – across aesthetics, periods, and styles spanning his career of some 50 years. Salomon believed that animal fauna is the best tool to express true human nature, especially in the Middle East’s environment. His subject matter on human beings through the wild animal will help generations to come ponder the existential human experience.

[1] Tavi Salomon. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 23 August 2023.

[2] Farid Abu Shakra. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 27 December 2022.

[3] Gideon Ofrat. “Beauty and the Beast” in Edwin Salomon, edited by Jacques Soussana. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991.

[4] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Mechira Pumbit, Meiri Print: Holon, 2003, 32.

[5] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 104.

[6] Spirit of Creativity: Resistance Through Art During the Holocaust [Exhibition]. (2023). The Museum of Holocaust Art, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

[7] Jean Ancel(2002). History of the Holocaust – Romania (in Hebrew). Israel: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-157-8.

[8] Jean Ancel (2002). History of the Holocaust – Romania (in Hebrew). Israel: Yad Vashem. ISBN 965-308-157-8. For details of the pogrom itself, see volume I, 363–400.

[9] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, p. 11.

[10] Spirit of Creativity: Resistance Through Art During the Holocaust [Exhibition]. (2023). The Museum of Holocaust Art, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

[11] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, 56.

[12] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 104-105.

[13] Douglas Murray. (13 October 2023). ‘You are not alone’: A message to the Jewish people. The Spectator.

[14] Haim N. Finkelstein. Surrealism and the Crisis of the Object. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University Microfilms International, 1979.

[15] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Towards 1958 – On the Human Condition’, 2008, 11.

[16] Gideon Ofrat, ‘Why is There No Jewish Surrealism?’, 2014, 116.

[17] Dalia Manor, From Rejection to Recognition: Israeli Art and the Holocaust, 1998, 256.

[18] Dorit Kedar. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 12 October 2022.

[19] Yael Guilat,. The Turning Generation: Young Art in the Eighties in Israel

[דור המפנה; אמנות צעירה בשנות השמונים בישראל]. Oranim Academic College of Teaching. Kiryat Sde Boker: Ben Gurion Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, 2019.

[20] Jacob Gildor. (Accessed 6 January 2024). Jacob Gildor. https://www.jacobgildor.com/bio2.

[21] Tavi Salomon. (2021, April 19). Edwin Salomon [PowerPoint slides]. Art History Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Research Seminar of Art History Spring 2021. Zoom Seminar.

[22] Sigal Barkai. ‘Neo-Diasporic Israeli Artists: Multiple Forms of Belonging’, 2021, 18.

[23] Amon Raz-Krakotzin. “Exile, History and the Nationalization of Jewish Memory: Some Reflections on the Zionist notion of History and Return,” Journal of Levantine Studies, 3.2 (Winter 2013), 37.

[24] Jonathan Silver, Senior Director of Tikvah Ideas, Warren R. Stern Senior Fellow of Jewish Civilization. (2023). 50th Anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. Tikvah Ideas.

[25] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Mechira Pumbit, Meiri Print: Holon, 2003. 15.

[26] Natan Zach, ‘The Animal Language of Edwin Salomon’, 1987, 8.

[27] Gideon Ofrat, Edwin Salomon’s Fauna, 1987, 1.

[28] Edwin Salomon, Jacques Soussana, ed. Jacques Soussana – Graphics: Jerusalem, 1991, 97.

[29] Farid Abu Shakra. Interview. Conducted by Jackie Frankel Yaakov. 27 December 2022.

[30] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Ravgon Ltd.: Herzliya, 2006. 46.

[31] Tavi Salomon. (2021, April 19). Edwin Salomon [PowerPoint slides]. Art History Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Research Seminar of Art History Spring 2021. Zoom Seminar.

[32] Edwin Salomon, Tavi Salomon, ed. Ravgon Ltd.: Herzliya, 2006. 28.

Art historian and critic Dalia Manor investigates the phenomenon that Holocaust-related subjects have been minimalized and marginalized in Israeli art. As with Israeli quasi-Surrealists Mordechai Ardon, Naftali Bezem, and Samuel Bak, Salomon’s symbolic, quasi-Surrealist visual language takes a hard look at the vicious side of humanity and its outcomes. Some human conduct that Salomon examines is influenced by faint childhood memories from the period of the Holocaust when Nazis displaced and dehumanized Jews; some is influenced by Communist violence and brutality seen as a young man (as portrayed in his Communist Torture, a portrait of Salomon’s friend); and as time goes on, some by the wars and existential anxieties of the young State of Israel. The Israeli art establishment was focused on form, not narrative, and language, not symbol. The taboo of the Holocaust was not of interest, but passé. Manor reflects that:

“…despite the wide acknowledgement of the tremendous impact of the Holocaust on life in contemporary Israel the subject remained relatively marginal in the art even within the context of relevant issues of anxiety and identity”.[17]

Inspired by Ardon, Bezem and Bak, upon his move to Israel in 1961, Salomon boldly worked to find his own language of signs and symbols, and also dealt with the taboo subject of the Holocaust. For example, Holocaust reflected directly on Nazi dehumanization tactics against Jews, a theme that would reverberate in Salomon’s artworks for decades. Through his unique animal imagery Salomon shows the rejected few in existential crisis brought on by the onlooking cruel masses and harsh officials of the regimes gawking at Jewish “otherness.” Salomon’s Bighorn, painted in 1980, shows an authority figure shepherding the masses up a treacherous mountain, with a smoky doom-filled sky of ashes alongside. Salomon’s use of marabou storks, rats, and fish schools reoccurs, shedding light on Salomon’s psychological distress around the stereotyping of exiled, frail, and/or submissive Jews, who in his memory were doomed to be persecuted and annihilated.

The Salomon of the Young State of Israel: A “Radicant” Art Immigrant Voice

Dorit Kedar (born 1948), an Israeli author and researcher specializing in gender and religion and longstanding colleague of Salomon’s and educator at HaMidrasha School of Art, recalls that Salomon loved classical Western culture and philosophy. He had trouble being understood in the local Israeli art scene, often on the outskirts of the dialogue on art of the HaMidrasha faculty he taught on for over a decade.[18] HaMidrasha attempted to educate its art students conceptually as “artists” and expected that they would develop their technical skills independently, in accordance with their individual needs. It was in this milieu that Salomon brought up a generation of sabra/native Israeli artists, from Haim Maor (who studied under him from 1961-68 and went on to be a full Professor of Art at Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva) to Yigal Ozeri (a leading Photorealism painter now based in New York City). Regardless of his personal painting prowess and excellence as a mentor, Salomon still felt an odd man out, as he did not conform to the style of his colleagues. During the rise of conceptual art in Israel in the 1960s and 70s, art for which the idea behind the work is more important than the finished art object (some works of conceptual art may be produced by anyone following a set of written instructions), Salomon still focused on the fundamentals and excellence of technique in his own artwork.

Salomon honed his unique, animal-Surrealistic motif as an Israeli artist in the 1980s. In 1983 Salomon won the Prize for Creativity from the Beit Hatanach (Bible Museum), Tel Aviv – a venue primarily outside of the artistic circle that displays permanent exhibits depicting the times of our forefathers, but which also has temporary exhibits of art related to the bible, Judaism and the Land of Israel. Edwin and his contemporaries were encountering the Neo-Expressionism of the international scene and finding their own expressive modes of representation. Israeli artists from this era, such as Moshe Gershuni, tended to work with blood-red paint, as if renewing a blood-bound covenant with the Land. Salomon’s blood red, which runs throughout his decades of painting, including Prayers pictured here, have tinges of this theme in its hue. Here a pack of tigers roar to the abyss of the heavens in prayer. One tiger slightly stands out – an individual in contrasting, strong yellows against the pack. Only the tints of red and blue coming through the darkness of the background help distinguish the wider masses from endlessness beyond the canvas.

The 1980s were a transitional period for Israeli art, marking the beginning of contemporary art in Israel. There was a break away from the unity of formative ideas of Israeli identity as a new, robust generation of artists rose to the art scene. Professor of Visual Culture and Art History Dr. Yael Guilat calls the young artists in the 80s in Israel ‘The Turning Generation’ [דור המפנה]. Guilat explores how ‘The Turning Generation’ revealed a generation of artists who were forced to dismantle myths and break previous paradigms; a generation of young female artists who worked in a male-dominated field; a young generation that was accused of being reactionary and unsophisticated, but whose work was characterized by a strong and urgent artistic and political expression; a generation that acted in an unprecedented burst of energy, and for whom art was a multi-channel field of action, invention, protest, and disillusionment. The young artists that emerged from the beginning of the decade both shaped it and were shaped by it, as is reflected in changes that were made in the field of curation, in the medium field, and in the thematic-stylistic field. Looking at the multi-faceted portrait of the younger generation of artists who worked in the 1980s reveals the collapse of the imagined portrait of Israeli society.[19]

The energy of ‘The Turning Generation’ renewed Salomon’s inspiration. The 80s were a decade of tremendous output by Salomon and a push to participate in exhibitions, even at venues at the margins of the art scene of the time. The 1980s brought more private and public gallery spaces and alternative exhibition venues, which Salomon used as an opportunity to exhibit his works more often. This included his participation in several one-man shows in Israel, as well as group exhibitions in Israel, Europe, and the USA. Like others of this time period who did not fit into the zeitgeist – the Israeli style of art Want of Matter [דלות החומר], which utilized meager creative materials to be socially critical – Salomon remained outside the mainstream and distinct from the definition of ‘Israeli art.’ Despite that fact, Salomon wanted to be responsible for the public seeing his own art, instead of waiting for a curator to discover him, and successfully exhibited throughout the decade.

In 1980, Israeli artist Jacob Gildor (born in 1948) was among the founders of Meshushe (Hexagon) group, which aimed to introduce Surrealist art to the Israeli art space – still dominated by abstract and conceptual art movements at that time. Back in 1971, Gildor had been invited by the Surrealist artist and teacher Professor Ernst Fuchs to Reichenau, Austria, to learn the master’s unique technique in tempera. A close friendship was forged between the teacher and student, which opened the young artist to the Surrealist movement and led him and his peers to establish Meshushe. The founding group consisted of Gildor and five other Surrealists: Baruch Elron, Yoav Shuali, Arie Lamdan, Asher Rodnitzky, and Rachel Timor. The Meshushe group held 10 exhibitions throughout Israel. While the exhibitions were warmly received and admired by the Israeli audience, Meshushe’s Israeli attempt at the escapism of Surrealism never managed to enter the Israeli Canon of Art critiques.[20] Surrealism did not find admiration in the Israeli art scene. It did not speak to the intensity of ‘The Turning Generation’ and its urgent artistic and political expression on the present moment in Israel in the 1980s. Meshushe found itself marginalized and irrelevant. Ultimately, each artist went on to explore a variety of other styles, each finding it hard not to relate to the history, symbols, and narrative of the Jewish people and the present Israeli landscapes or cityscapes they were encountering in their art. While Salomon and Gildor had some overlap of influence by the Shoah (Gildor was Second Generation), the impact of Surrealism, and exploration of woe, they worked in parallel spaces, not recognizing the similarities of their styles and subject matters sprouting from their mutual hometown of Holon, Israel. It is unclear why Salomon was not involved with this group.

At one point in Salomon’s career – despite his home in Holon, art pieces explicitly exploring the 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, and 1993 Oslo Accords, and having his artwork displayed in the President’s residence in Jerusalem – he was still told by the leading Israeli art historian Gideon Ofrat: “You are not an Israeli painter. [אתה לא צייר ישראלי]”[21] An artist’s relations between homeland and Diaspora are complicated as they negotiate their identity through a complex psychological process of dramatic self-adjustment. As Sigal Barkai concludes:

“A new negotiation between local and universal cultural identities changes the

demarcation of Israeliness, and obscures outdated national ideas such as the negation of the Diaspora. It allows for mutually-nourishing artistic and societal formations that inspire the Israeli, Jewish, and global ‘imaginary community.’”[22]

Israeli art is eclectic, and very hard to define, specifically due to global mobility and influence, as well as post-immigration hyphenated identities – like Salomon’s Romanian-Israeli identity. The ethos of negation of exile, and the attempted melting pot of perceived ‘weak’ Diaspora Jews into the new native Israeli identity of strength, greatly troubled Salomon. Salomon was proud of his Romanian upbringing, despite ultimately being persecuted and rejected because he was a Jew. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin suggests:

“In its elementary and most common sense, the phrase “return to history” was perceived as signifying the intention of turning the dispersed Jews into a sovereign national subject that can determine its own fate and assume responsibility for its own existence. In that sense Zionism was considered to be the solution to the Jewish question and the conclusion of both the crisis of Jewish existence and the prominent role of anti-Semitism in modern culture. It was based on the accepted interpretation of the term “history” in nineteenth-century culture, which made the nation its exclusive subject and carrier.”[23]

Negation of exile is thus a cultural force in the construction of Zionism from the late nineteenth century to the present. It builds on the denying of specific features in Jewish histories that may “dangerously” contradict the image of national revival in the Land of Israel. Thus, it is only logical that Salomon’s European-influenced paintings were hard to place in the Israeli art scene, marginalized by his contemporaries – in a place of bitter isolation, an empty space filled by his studio.

Historian and educator Dr. Ori Soltes considers Israeli art “radicant art.” A radicant plant grows its roots, spreads, and adds new roots as it advances, with multiple enrootings along the way, just like an immigrant and their art. Salomon’s career in many ways is an example of immigrant radicant art adapting, evolving and enrooting anew along one’s journey of immigration to new places, and the identity transformation that coincides with changes of location and a new local reality and mindset. Salomon shifts from Realism and portraiture in Romania, to Cubism and Abstraction and Neo-Expressionism in young Israel, to then the quasi-Surrealistic and metaphoric animal jungle of his mind on canvas as the years go on and he and the Israeli art scene mature.

Artistic play becomes a therapeutic means of working through strong emotions due to social and internal dissonance for Salomon. The gradual merging of homeland and Diaspora bring forth a new cultural identity and a variety of ways to belong, the art being a means to an end of psychological processing and reconciliations, brought on by new and converging global and mobile realities.

Salomon explores not just Jewish survival, but also the struggles of masculinity and motherhood. He explores predators hunting their prey. He explores the dark sides of human nature, perhaps in ways that were indeed taboo and ahead of his time, as a radicant artist enrooting himself in the intensity of the Middle East. We can clearly see over time through his artwork a nuanced change in Salomon as an individual artist, but also of the wider social scene of his day, deriving meaning from and giving form to life experiences in the wake of wars, especially the 1982 Lebanon War.

In Fall 2023 we marked the 50th anniversary of a formative event in the Cold War, a defining moment in the geopolitics of the Middle East, and one of the direst trials for the young state of Israel: the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Though this War ended in a military victory for Israel, the invasion by Egypt and Syria and the days of anguished battle that followed threatened the very existence of the Jewish state. The war had dramatic and long-range impact as well: the politics, culture, and national-security strategy of Israel were forever altered, as were the USA, the Soviet Union, Egypt, and the rest of the Arab world likewise deeply affected.[24] Salomon investigated this existentially precarious moment for the young Jewish state in his pieces The Tank and Yom Kippur the very next year, 1974. The blood red of Jewish spirit is depicted in Yom Kippur with tanks pouring out light, driven by bulls above in a herd of strength, almost a divinely protective pillar of cloud: a very moving exploration of this crisis. The animal imagery and symbolism portray defensive strength and ultimately victory for Jewish survival. Yom Kippur is also an early example of him finding his artistic voice in his unique, existential art style of ‘Like Animals,’ investigating human behavior through quasi-Surrealist animal imagery – the style he spends the majority of his career exploring, perfecting, and exhibiting around the world.

Salomon’s ‘Like Animals’ Existential Art: Investigating Human Behavior through Surrealistic Animal Imagery

Postwar Surrealism established itself in relation to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism emphasizing that our acts create our essence, the humanist cultural policies of the French Communist Party articulated by Louis Aragon, and the re-emerging Parisian avant-garde. A Surrealist imposes meaning on the absurdity of the universe in an artistic way; effectively creating his own reality. The paintings of Surrealism, which are open to interpretation, can become whatever the viewer decides. In the face of existential agony, the existentialist exercises the human freedom to choose a meaningful life course, while the Surrealist chooses to impose meaning on elemental chaos through art. Salomon’s animals seem to work through the chaos of human violence and survival, partially focusing on the basic existential givens, including death and isolation.

Surrealism was a melting pot of avant-garde ideas and techniques still influential today, especially the introduction of chance elements. This new mode of painterly practice also blazed a trail for Abstract Expressionists, such as the Surrealist navigation of the unconscious and the Jungian symbolism of Jackson Pollock’s action painting. According to the theory of psychologist Carl Jung, symbols are language or images that convey, by means of concrete reality, something hidden or unknown and dimly perceived by the conscious mind. These symbols can never be fully understood by the conscious mind. Salomon included chance and a release of the unconscious in his technique for paper with oils on which he used special chemicals to create burst effects, releasing the image of his subjects from his paint layers, like in Camouflage.