Zohar Atkins

Can One Delegate Holocaust Metaphors? [Excerpted From Talmud Tractate Pseudo Avodah Zarah, Perek AOC]

MISHNA

A Gentile who makes a Holocaust metaphor is obligated to death.

But a Jew who does not make a Holocaust metaphor is

cut-off.

GEMARA

The sages asked

Can one delegate Holocaust metaphors?

On the one hand, it was taught that “all are obligated to regard themselves

as though they were personally liberated from [alternative manuscripts read: abandoned in] Auschwitz.”

But it was also taught that one can hire a scribe

to write a Torah scroll even though the verse teaches

“And you shall write for yourself a scroll.”

Yourself—this means a fellow Jew.

What do we learn?

Marx says that money turns the other into an extension of oneself.

But Anderson says this only works within an imagined community.

As people say, “one cannot hire a turtle to say Kaddish for one’s cat.”

Thus, the sages concluded that one can delegate Holocaust metaphors

provided the one hiring and the one being hired both have the intention of fulfilling their obligation.

But what about in the case where one purchased a Holocaust metaphor online

or through a third-party?

Rav permits and Shmuel forbids.

What’s the reasoning?

Rav says the relationship itself is essential to the act and Shmuel says the content stands (independent of the relationship).

By Shmuel’s reasoning, though, I should be able to purchase a Holocaust metaphor from a Gentile?

Yes. That’s true.

But Shmuel forbade this?

Yes, lest the money from the transaction support BDS.

But if that were so, then let Shmuel forbid all transactions with Gentiles?!

Rather, the reason must be that Shmuel held that we are dealing only with a case of political foes, not with Gentiles as a general class. [The Meiri notes that in our time the category of political foe is purely theoretical and totally inapplicable.]

Or if you want, say that Shmuel was concerned with job creation and wanted to ensure that even the poor might be able to support themselves through this hobby.

But isn’t making Holocaust metaphors a craft?

As it says, “And Bezalel assembled the dolphin wood?”

Shmuel held that it is not a craft. As it says, “Let each person bring a half-shekel.”

***

A poem is not a thesis statement but an argumentative journey, a search for that which could not be revealed were the poem not written, and, through reading, rewritten. How’s that for a thesis statement? In this, it resembles the Talmud. Or rather, we can say, Talmud is poetry in a fundamental sense.

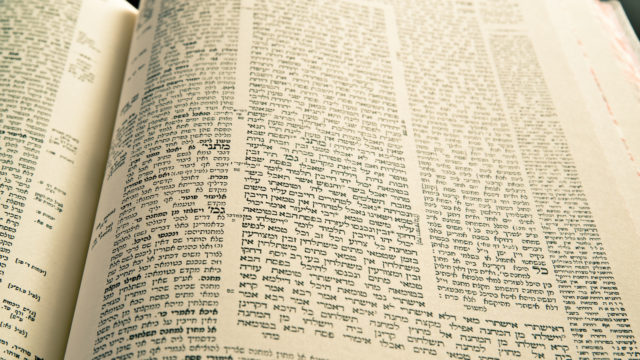

Charles Olson writes that the units of the poem are the breath and the line. A line break is a visual representation of a change, a turn, not just in sonic velocity but in the attitude or stance of the poem. A poem is a coherent series of disruptions, a curated gathering of dissonances, what David Antin calls “radical coherency.” While there are no deliberate line breaks in the Vilna Shas—making the Tamlud read as a kind of prose poem—Talmudic form also reads as a series of disruptions. Yes, one can find thematic and logical coherence between words, phrases, and arguments, but this coherence is an emergent property that grows out of a finer and subtler sense that the ground on which the Talmud stands is a dark abyss. According to legend, when the Vilna Gaon praised Reb Zusha for knowing an obscure sugya in the Yerushalmi Talmud, Reb Zusha’s response was that he didn’t know the text, but that he got his knowledge from the same place the Yerushalmi got its knowledge. If Reb Zusha’s example is paradigmatic, and I believe it is, then Talmud is, above all, a way of being, a way of thinking, and only secondarily a calcified text, a leather bound book. It is, after all, oral Torah. Poetry, too, in its origins was oral, and like Talmud, now occupies the strange position of often being page-bound.

Dramatic dialogue accounts for about 30% of the Babylonian Talmud, but the glue that makes Talmud what it is is the disembodied voice of the stamm[aim], the narrator[s], a literary conceit by which the Talmud talks to itself, recasting the historical, diachronic dialogue of earlier Tannaitic and Amoraic sages as a synchronic and deliberately anachronistic discussion in which later voices talk to, with, and back at their predecessors. I offer a mash-up here of Talmudic satire and cultural commentary, above all, not to convince anyone of anything prosaic (for that you can read my twitter), but rather to delight in Talmudic form and language and to show its relevance for bringing criticism and self-criticism to discussions that are too often one-dimensional, overdetermined, and stale. Talmud Torah is a way of life, a high calling. But Talmud Torah, I believe, should be expanded to include not just the study of ancient texts but also the production of our own. While it may be the case that we moderns or postmoderns can only parody and imitate the past, it may also be the case that irony and parody are themselves traditional forms. Or as Bruno Latour used to say, “we have never been modern.” Tzarich iyun. Fictive Sugyot are not necessarily endorsements.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-100x75.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.