Zohar Atkins

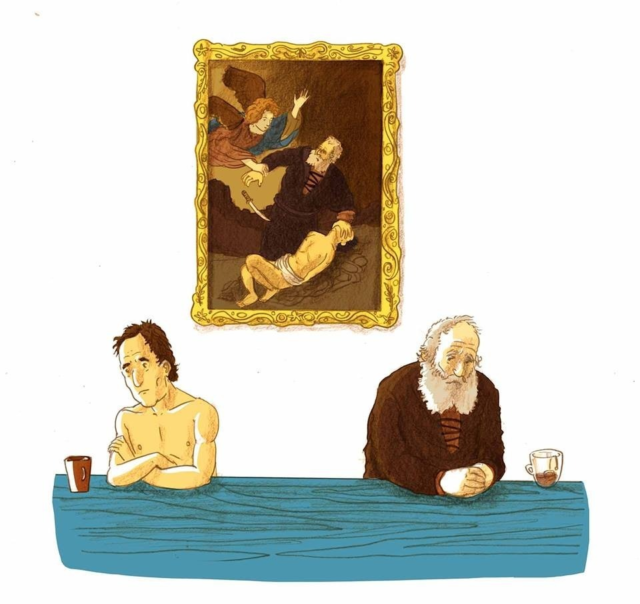

Every angel’s abrupt, placing some ram

in the foreground where once

there was only an altar.

There are things you learn you knew

before being born

at the end of your life—

that resignation is mourning

in advance, like paying a bill

before your statement is ready.

That self-help is astrology

without stars.

That medicine works

in worst-case scenarios

and faith saves

save when it doesn’t.

At the end of your life

you do not know it’s the end

though you practice dying

recite a confession each night

you can’t know is a confession.

The life you want to live, yet can’t

appears as a ram caught in the hedge

while a disembodied voice simulates

the coo of your infancy

which you interpret

“Do not raise your hand

against the lad,”

this moment,

your only moment,

the one you love, now.

You don’t need a knife

to substitute another life

for this one.

What do we give up by focusing our attention on what is immediately in view? What do we overlook when we look only into the distance? Decision comes from the Latin, de-cidere, to kill off possibilities. Every life-choice, small or large, conscious or unconscious, intentional or accidental, is a sacrifice. Sacrifice exists because we are mortal, temporal creatures. “Abraham got up early in the morning.” Teshuvah, repentance, is at once a return to yourself, a re-commitment to live your life in a certain way, and a sacrifice of all the lives you cannot live. Teshuvah is at once a movement into the past, of “returning,” and a movement towards an uncertain and inimitable future (making Maimonides’s idea that complete Teshuva means not doing the same sin twice a kind of absurdist twist on Heraclitus). Teshuvah describes not just a process of penitence, but the structure of time itself, in which, as Heidegger says, we are “always ahead of ourselves” and “thrown.” Hard choices presume deciding between competing values, competing aspects of our identity; yet the choices we make make us who we are, manifest the latent knowledge we had but didn’t know we had until we were forced to decide. Abraham may not sacrifice Isaac, but the decision to the ascend the mountain cannot be undone by the sacrificing of the ram in his place. This midrashic poem is a meditation on the paradox of living in time, of both knowing and not knowing, of being the kind of people we are because of what we choose and of choosing what we do because we are the kind of people we are. Teshuvah presumes agency, yet the source of our agency remains, experientially and metaphysically, a matter of mystery, if not grace.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.