Alan Jotkowitz

In memory of all our holy soldiers and brethren who fell al kiddush Hashem, and with the fervent hope and prayer that the hostages will return safely and the injured will have a speedy recovery.

Ne’ilah is a singular and unique time of the year. For many Jews, it is when they feel closest to Hashem. And, for thousands of years, Jews of all denominations and beliefs have gathered in their synagogues, sometimes at great personal danger, to pray (and cry) this final prayer of Yom Kippur together.

What exactly are we praying for during Ne’ilah, and what should one think about at this auspicious time of year? Of course, there is no right answer to this question. But I would like to share what I have learned from my teachers over the course of a lifetime.

The Ne’ilah of Teshuvah

For over 40 years, Rav Yehuda Amital led the Ne’ilah prayers in the yeshiva he founded, Yeshivat Har Etzion. And before he walked up to the amud to lead, he gave a short hortatory lecture in a singsong voice. The theme of the lecture each year was usually the same, and he would invariably quote the same two midrashim that illustrated his points:

In order to merit the opening of the gates of heaven, we have to open the gates of our heart. With the words of the prayer “Open us a gate…,” we request divine assistance that will allow us to open our hearts – even just the tiniest opening:

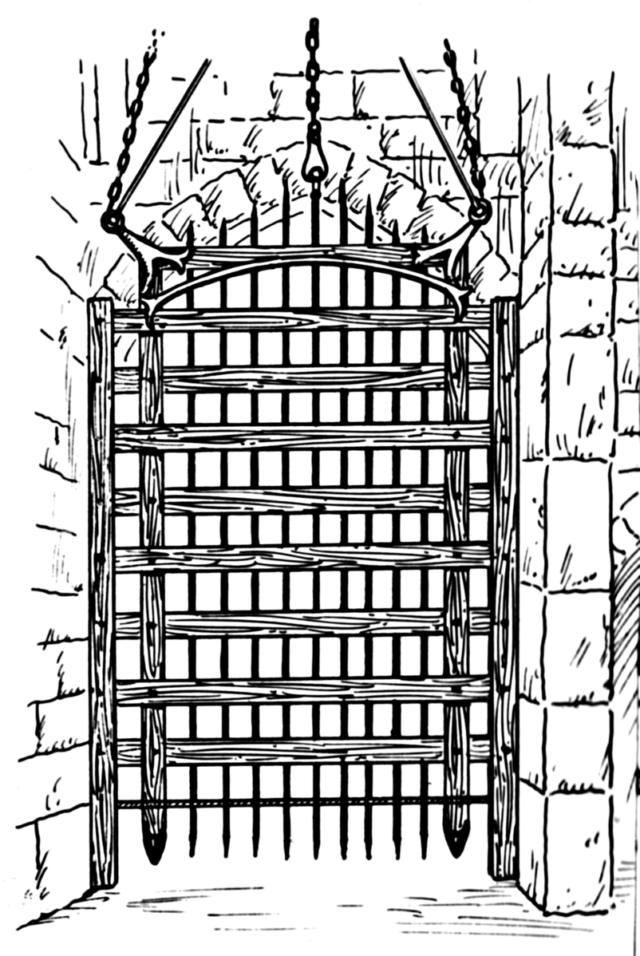

“My Beloved is knocking, saying, ‘Open for me’”- R. Yissa said “The Holy One, blessed be He, says to Israel, ‘My children, open for Me just one opening of repentance, be it as tiny as the point of a needle, and I will open for you openings (so wide) that wagons and carriages could pass through (Song of Songs Rabba 5:2).[1]

Rav Amital thereby taught that Ne’ilah is an auspicious time for teshuvah: Use this opportunity to repent and return to Him. And God promises that He will help.

He continued by referencing a question from the Yerushalmi (Berakhot 4:1): “What is the source of Neilah? R. Levi says: ‘Even if you make many prayers’ (Isaiah 1:15)―from here we learn that one who prays at length is answered.” And the midrash on Song of Songs teaches:

“I rose up to open for my beloved, and my hands dripped with myrrh, and my fingers with flowing myrrh, upon the handles of the lock” (Song of Songs 5:5). “I rose up to open for my beloved”―this alludes to Shaharit. “And my hands dripped with myrrh”―this alludes to Musaf. “And my fingers with flowing myrrh”―this alludes to Minhah. “Upon the handles of the lock”―this alludes to the Ne’ilah prayer.

Ne’ilah is the culmination of all our Yom Kippur prayers and the end of a process that began on Rosh Hodesh Elul with the blowing of the shofar as a call to repentance. It is our final chance to return to God before the gates of heaven close and our fate is determined. As Rav Amital stressed, Ne’ilah is the time to take advantage of this opportunity and gift from God. “Open us a gate…”

The Ne’ilah of Tefillah

Rav Amital’s longtime partner Rav Aharon Lichtenstein listened to this sermon for decades and commented: “In these words [of Rav Amital] there is certainly an element of truth… and nonetheless, from my perspective, this is not the main message of the Ne’ilah prayer.”[2]

What, then, is the essence of Ne’ilah according to Rav Lichtenstein? The same Yerushalmi provides another basis for Ne’ilah:

R. Hiyya taught in the name of R. Yohanan, R. Shimon ben Halafta in the name of R. Me’ir, “As she [Hannah] was praying at length before the Lord” (I Samuel 1:12)―from this we learn that all who pray at length are answered.

Ne’ilah is fundamentally different from all the other prayers of Yom Kippur, not only on a theological level but from a practical perspective as well; for example, unlike the other prayers, we omit the long vidui and say selihot. And its model is the prayer of Hannah. Her prayer was a plea for mercy from Hashem and so, too, should be our Ne’ilah. At this time, all we can do is cry out to our Father in Heaven and ask for His mercy. The time for teshuvah is over, and all we have left is to place our fate at the mercy of Hashem. Rav Lichtenstein writes:

However, as dusk approaches, when the conclusion of the day and its Atonement is on the horizon, we turn to God and say: Master of the Universe, we have been working on ourselves all year and especially since the beginning of Elul, weighing and measuring our sins, and all of Yom Kippur we have been striving and groping and hoping. But now at the end of the day, we have only one thing left, and that is to cast our hopes and prayers upon You.[3]

This motif is expressed in the unique liturgy of Ne’ilah. As discussed in Yoma 87b, the centerpiece of Ne’ilah is the Mah Anu poem, translated as:

What are we? What is our life? What are our acts of kindness?

What is our righteousness? What is our deliverance?

What is our strength? What is our might? What can we say before You,

Adonoy, our God and God of our fathers? Are not all the mighty men

as nothing before You? Famous men as though they had never been?

The wise as if they were without knowledge? And men of understanding

as if they were devoid of intelligence? For most of their actions are a waste and the days of their life are trivial in Your presence.

The superiority of man over the beast is nil for all is futile.

As the sun is setting on the Day of Atonement, we acknowledge our human limitations and worthlessness before God and put our faith in His goodness and grace. If we are truly worthless and condemned to a life of sin, on what basis can we expect forgiveness? Perhaps the answer to this question is best expressed in the short tefillah we say after the blowing of the shofar on Rosh Ha-Shanah:

On this day, the world came into being… all the creatures of the worlds—whether as children, or as servants; if as children, have compassion on us as a father has compassion on his children!

Just as a parent will always forgive their child, we hope and pray that God will forgive His children.

The Ne’ilah of Love

It has been stated: “R. Yosei ben R. Hanina said: ‘The prayers were instituted by the Patriarchs.’ R. Yehoshua ben Levi says: ‘The prayers were instituted to replace the daily sacrifices’” (Berakhot 26b).

If Avraham instituted Shaharit, Yitzhak instituted Minhah, and Ya’akov instituted Arvit, one can argue that Hannah is the originator of Ne’ilah. Alternatively, if the three prayer services parallel elements of the Temple service, Ne’ilah must also be a reminder of a particular Temple service.

R. Menahem Azariah of Pano (“Rama Mi-Pano”), in his Sefer Avodah U-Musafin, maintains that Ne’ilah was instituted in remembrance of the removal of the spoon and shovel from the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim (Holy of Holies), which was the fourth and last time the Kohen Gadol entered the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim on Yom Kippur.[4]

Hizkuni (on Leviticus 16:23, s.v. u-va Aharon) questions why this “service” was necessary. Why did the Kohen Gadol have to enter the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim again? Why couldn’t he have simply left the spoon and shovel there until next year, or alternately dragged it out without entering? It seems that this “entering” is an integral part of the service of the day, entailing immersion and a changing of clothes.

Furthermore, what is the need for this extra encounter with the Divine Presence? The children of Israel were already forgiven with the acceptance of the offering of the goat and the bullock, which were intended to serve as conduits for the atonement of Israel. According to R. Ya’akov Medan,[5] the reason the Kohen Gadol entered the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim one final time was to give him one last opportunity to pour out his heart and soul to God and speak directly to Him without an intermediary, about his hopes, fears, and aspirations for the coming year. The Kohen Gadol enters the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim this last time, not to beg for forgiveness but simply to talk to God.

For 40 days we have been busy with the hard work of teshuvah and changing ourselves. But have we taken the time to talk to Hashem, to express our deepest thoughts, feelings, and fears, and to pray for what is truly important to us? As of Ne’ilah, we have already been cleansed of our sins and have a special time to be with God.

Rav Medan even identifies the exact time of the day when the Kohen Gadol entered the Kodesh Ha-Kodashim this final time, when the congregation chanted:

[Nevertheless], You have set man apart from the beginning, and recognized him [as worthy] to stand before You.

God has given man the unique opportunity to stand before Him, if not as an equal then as a partner.

Indeed, Rav Amital and Rav Lichtenstein similarly emphasized this relationship aspect of Ne’ilah. Rav Amital writes: “Prayer can also express the second aspect mentioned above – seeking closeness to God… Ne’ila is a new prayer, a prayer of repentance, a sincere seeking of closeness to God.”[6] And Rav Lichtenstein: “At the time of Ne’ilah, our connection to Ha-Kadosh Barukh Hu isn’t an abstract one but rather a direct and emotional relationship with Him.”[7]

The Ne’ilah of Tears

Notwithstanding the closing of the gates at the time of Ne’ilah, Berakhot 32b teaches that the gates of heaven are never closed to tears:

R. Eliezer also said: From the day on which the Temple was destroyed, the gates of prayer have been closed, as the verse states, “When I cry and call for help He shuts out my prayer.” But though the gates of prayer are closed, the gates of weeping are never closed, as the verse states, “Hear my prayer, O Lord, and give ear unto my cry; keep not silence at my tears.”

The gates of heaven are never closed to our tears. But what are these tears? They may be the tears of teshuvah, as Rambam writes (Hilkhot Teshuvah 2:4) “Among the paths of repentance is for the penitent to constantly call out before God, crying and entreating.”

Alternatively, they are the tears of supplication and beseeching of Hashem, as in the prayer of Hannah: “And she was bitter in spirit, and she prayed to the Lord, and wept” (I Samuel 1:10).

But this Yom Kippur, our tears at Ne’ilah will have another dimension, tears of avelut. We all mourn the hundreds of soldiers and civilians who died in sanctification of God’s name this year and will be crying together as a people this Ne’ilah. And we will also be praying together as a people that our Father in Heaven hears the final blast of the shofar which heralds our ultimate redemption.

[1] Yehuda Amital, When God Is Near: On the High Holidays (New Milford, CT: Maggid Books, 2015), 251.

[2] Aharon Lichtenstein, Seek Those Who Seek You [Hebrew] (Rishon Le-Tzion: Yediot Aharonot, 2023), 142. My translation.

[3] Aharon Lichtenstein, Return and Renewal: Reflections on Teshuva and Spiritual Growth (New Milford, CT: Maggid Books, 2018), 94.

[4] I thank R. Yair Kahn for pointing out this source to me.

[5] I heard this directly from Rav Medan in a 2019 shi’ur at Yeshivat Har Etzion.

[6] Yehuda Amital, When God Is Near, 256.

[7] Aharon Lichtenstein, Seek Those Who Seek You, 148.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.