Zev Eleff

A number of years ago, something strange occurred at synagogue. I was distracted by a middle-aged visitor sitting behind me at the Young Israel of Brookline, an Orthodox synagogue located in a comfortable Boston suburb. The gentleman was not trying to disturb. To the contrary, he was fixed on the prayers, responding in all the correct places so that his young son might learn from his good example. In a clear and instructive voice, he responded “amen” after each blessing and articulated a fine Aramaic pronunciation to the responsive portion of the Kaddish. Toward the end of the morning service, the father sang aloud to the Alenu prayer in a voice that seemed to rise above the rest of the congregation.

Then he paused. The rest of the worshipers continued. In melodious refrain, the congregation chanted the next line, a conflation of two verses from Scripture that contrasts Israel’s relationship with God to those who “bow to vanity and emptiness and pray to a god who will not save.” Yet, the man behind me kept silent. After the service I considered asking, but I thought better of it.

The answer was obvious. To this Jew, the line needlessly attacks his Protestant and Catholic friends and coworkers. They do not curse and poke fun at his religion in church so why should he cause so much theological commotion at synagogue?

The evolution of Alenu and its anti-Gentile animus is well-documented. At the time Isaiah composed those biblical sentences—the verse is a confluence of Isaiah 30:7 and 45:20—he had in mind the cultic rituals of Mesopotamian idolaters. He certainly did not intend to blaspheme Christianity, a faith founded hundreds of years after the prophet’s passing. That changed thousands of years later, when Jews added the Alenu to the daily worship. By the thirteenth century, Jews freighted Alenu with gruesome anti-Christian meaning. In addition to reinterpreting the intent of Isaiah’s harsh words, some of the most bitter Jews in medieval Ashkenaz appended that Christians prostrate to a “man of ashes, blood, and bile,” thereby emphasizing Jesus’s unresurrected body. Moshe Hallamish and Israel Ta-Shma rediscovered this gruesome language in the 1990s and it has intrigued Judaica scholars ever since. Other Jewish worshipers developed the custom to spit in synagogue when they reached the word for “emptiness” since its numerical value (va-rik) equaled the Hebrew name of the Christian savior. Jews settled in Islamic lands also adopted the daily Alenu recitation and found a way to curse Muhammad, as well.

In time, Ashkenazic Jews fearing backlash self-censored their prayer books. Their prescience was confirmed in 1703 when King Frederick I of Prussia demanded that Jews in his kingdom excise the sentence. Liturgy scholar Ruth Langer has shown that while Jews deleted the offending verse, they replaced it with asterisks or other symbols rather than remove all indication of its existence. In all probability, then, worshipers concluded prayers with notions of anti-Christian “vanities” and “emptiness” for hundreds of years. In fact, it was not until the late nineteenth century that prayer books no longer left any trace of the anti-Christian device in the Alenu.

Jews brought these censored traditions with them to the United States. In truth, religious reformers concerned with Alenu’s particularistic message about the chosenness of the Jewish people revamped the prayer to better reflect all of mankind and their own universalistic sensibilities. On the whole, they accomplished these by deleting the “problematic” lines. But the more orthodox-leaning Jews retained the prayer with its catchy sing-song melody, save for its anti-Christian stanza. The omission remained even though anti-Jewish policies and threats no longer lingered.

Traditional exponents believed that they had eradicated “vanity” and “emptiness” from liturgical existence. And they were proud of it. In the Conservative Movement, the Rabbinical Assembly’s Prayer Book Committee briefly discussed the phrase but never paid it serious consideration when it commissioned the organization’s first prayer book in the 1940s. In 1978, a leading Conservative rabbi happily declared that the practice had ceased, even among the most rightwing segments. In his words, “no Orthodox synagogue which follows the Ashkenazic rite has taken steps to restore the deleted passage.”

The explanation, wrote Robert Gordis, was that “the line is no longer felt to be in harmony with the Jewish outlook.” That “outlook” was one of religious pluralism. Jews occupied an overrepresented space in the so-called “Tri-Faith” America. Their numbers hardly measured up to the Protestant and Catholic population but that did not seem to matter. Jews felt the pressure to justify their oversized share of the United States’ postwar “Judeo-Christian” principles alongside Protestants and Catholics. Consequently, they felt compelled—responsible, even—to smooth out some of their rougher anti-Christian edges. Alenu therefore remained unrestored and uncontroversial.

Gordis overstated his case, but not by much. A few prayer books migrated to the United States with the reinstated verse from Israel, where tolerance of Christianity was far less pressing. In addition, a number of Sephardic congregations that dotted the American coastlines still retained the full version of the Alenu since their forebears were not affected by Christian sanctions and censors. The slightly abbreviated edition was carried in most prayer books, including Philip Birnbaum’s well-used edition as well as the worship officially sanctioned by the Orthodox rabbis of the Rabbinical Council of America in 1960.

These were the prayer books with which my synagogue neighbor grew up. What is more, neither he nor any of the other Judeo-Christian American Jews detected a counterculture that disagreed with their viewpoint.

A more conservative current within American Judaism interpreted religious pluralism in the United States as a “freedom” to worship unrestrained of implications rather than a “responsibility” to abide by more liberal and congenial sensibilities. In April 1966, Milton Himmelfarb, a prominent Commentary editor, spoke for this emerging group. Similar to debates over censored portions of the Talmud, Himmelfarb opined that perhaps American Jews would be well served to bring back “the passage that the Christian censors deleted from our text.”

Others belonging to the Orthodox camp were of a similar mind but did not take action for several decades. The Brooklyn-based Mesorah Publications first experimented with the textual restoration in 1980. At that time, the publishing house better known by its ArtScroll imprint reinserted Isaiah’s harsh rebuke into the appendix of a pamphlet on the blessing (that includes Alenu) recited on the sun after it completes its 28-year solar cycle.

A year later, ArtScroll adopted a slightly more reserved stance when it printed the first edition of its daily prayer book. In that version, ArtScroll encased the verse in parentheses, as if to suggest that the reader serve as the arbiter of the moral dilemma. The democratic gesture was not completely genuine, however. The editors revealed their bias, adding a footnote that strongly encouraged that readers recite it. Still, the parentheses demonstrated that the matter was far from straightforward. More than anything else, perhaps, ArtScroll begged its readers to dwell on the fact that in America the traditional worshiper had a choice.

The defense of the refurbished liturgy argues that Isaiah and Alenu predate Christianity. An old tradition claims that Joshua composed the prayer while other pieces of Jewish lore maintain that it was authored in the Babylonian academy in Sura. In each case, the original intent of Alenu could not have been aimed at Christians. This line of reasoning offers no credence to the extra meaning that Jews poured into the prayer after each Crusade and pogrom. Instead, it celebrates the freedom to recite the original text in an American culture that does not restrict free speech and expression.

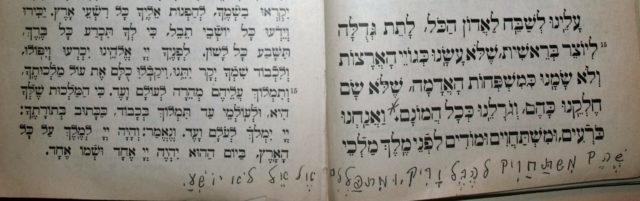

No one really seemed to mind ArtScroll’s revision. A Yale English professor voiced a certain displeasure of the “restoration of the nationalistic nastiness.” However, there is no evidence of other public complaints from traditional worshipers who were quickly smitten by the aesthetically superior layout of the new prayer book. To the contrary, while praying at a Young Israel on Long Island I found that a concerned worshiper took the time to amend an older prayer book that excluded the line (pictured above). In striking similarity to the individual’s Ashkenazic forebears, the no doubt pious Jew alerted the prayer book’s future users with an asterisk and reproduction of the missing passage at the bottom of the page.

Since the 1980s, hundreds of Orthodox synagogues in America have traded in their Birnbaum prayer books for one of the many available versions distributed by ArtScroll. In fact, the Rabbinical Council of America commissioned an edition of the ArtScroll rite. While the centrist rabbinical group insisted that its edition of the prayer book include a special prayer for the State of Israel, it included the fuller version of the Alenu prayer. More recently, a number of synagogues have dispatched with ArtScroll in favor of a more “modern” worship issued by Koren Publishers in 2009. On the Alenu score, however, Koren’s “North American” text mirrored the ArtScroll format: it offered the verse in parentheses, leaving it for the worshiper to determine its appropriateness.

Alenu is a paradox. For some the prayer is a declaration of our duties as good American pluralists, to suppress the ideas that divide us. For others it stands for the uniquely American privilege to worship without criticism or sanction. As for me, I remain transfixed on the parentheses that frame the debate and ultimately offer the reader final judgment on the matter. For me, then, Alenu is American Judaism, replete with all its remarkable tensions.

![Yom Yerushalayim: On Not Yet, Always Already, and the [Im]possibility of Crossing Over](https://thelehrhaus.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/The_Kotel_23908738216-238x178.jpg)

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.

Site Operations and Technology by The Berman Consulting Group.